5 Respiratory Diseases of Cattle

Respiratory diseases of cattle can be a tiny bit challenging because there are a fair few of them. As you read the notes, keep track of which diseases cause bronchopneumonia, interstitial lung disease, embolic pneumonia, pleuritis, or upper respiratory (nasal/tracheal) lesions.

| Course priority #1 | Course priority #2 | Course priority #3 | |

| Cattle |

|

|

|

Pneumonic pasteurellosis

Pneumonic pasteurellosis refers to bronchopneumonia caused not only by Pasteurella sp., but by any bacteria of the family Pasteurellaceae. It affects cattle of a variety of ages, including dairy and veal calves, and adult dairy cows in the winter. “Shipping fever” describes the same disease when it occurs in beef calves within several weeks of weaning, transport, and co-mingling with animals from other farms.

The major causes are bacteria of the family Pasteurellaceae: Mannheimia haemolytica, Bibersterinia trehalosi, Histophilus somni, and Pasteurella multocida. Note that Histophilus somni may also cause bacteremia and vasculitis that result in encephalitis (ITEME), polyarthritis, myocarditis, pleuritis, uveitis, and endometritis; individual animals can have several or only one of these diseases (i.e., calves with H. somni pneumonia may have just pneumonia, or concurrent pleuritis, ITEME, etc.).

All of these bacteria may be carried in the nasopharynx of normal calves. Disease is thought to require a predisposing cause, such as stress or viral infection. Viral infections occur when naïve stressed calves are mixed with calves from other sources. These viral infections impair respiratory defences by infecting ciliated epithelium to reduce mucociliary clearance, by infecting alveolar macrophages to reduce their antibacterial functions, as well as several other mechanisms. The viral infections also induce inflammation in the respiratory tract, and it is thought that this inflammation may worsen the responses to subsequent bacterial infections. Stresses of weaning, transport, crowding, reorganization of social groups, change in feed, water restriction, and adverse climatic conditions impair respiratory defences. Stress may also stimulate proliferation of bacteria in the nasopharynx, and induce a shift to a more virulent form. Cold stress (from changes in weather, and precipitation) reduces mucociliary clearance.

Mannheimia haemolytica produces a leukotoxin which causes necrosis of ruminant macrophages and neutrophils, thus impairing this important pulmonary defence mechanism.

Clinical signs are usually of acute onset and mainly reflect the acute phase response: fever, depression, anorexia, lack of rumen fill, and holding back from the feed bunk. Other clinical signs result from local effects within the respiratory tract: coughing, mucopurulent nasal discharge, tachypnea, dyspnea.

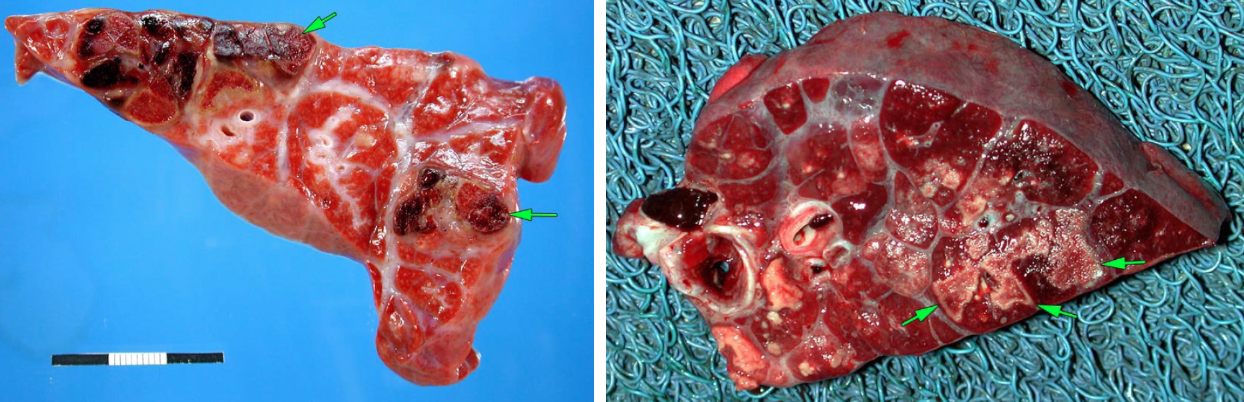

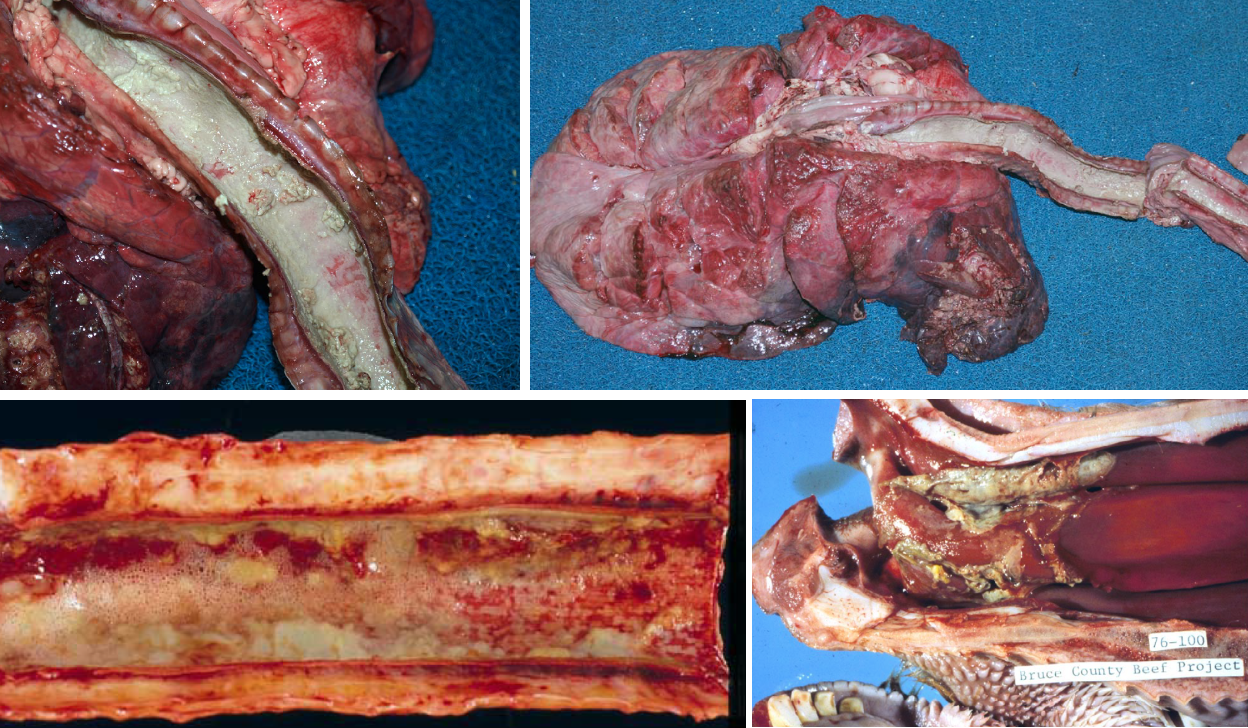

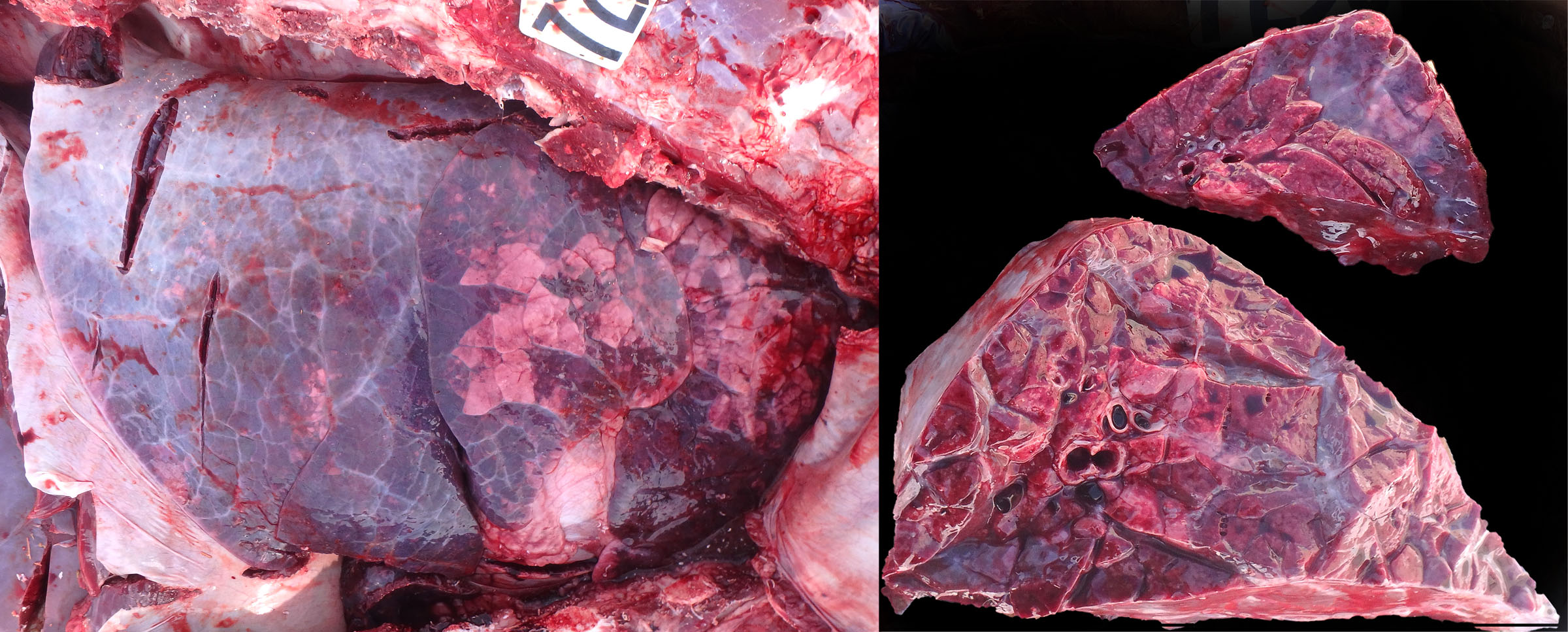

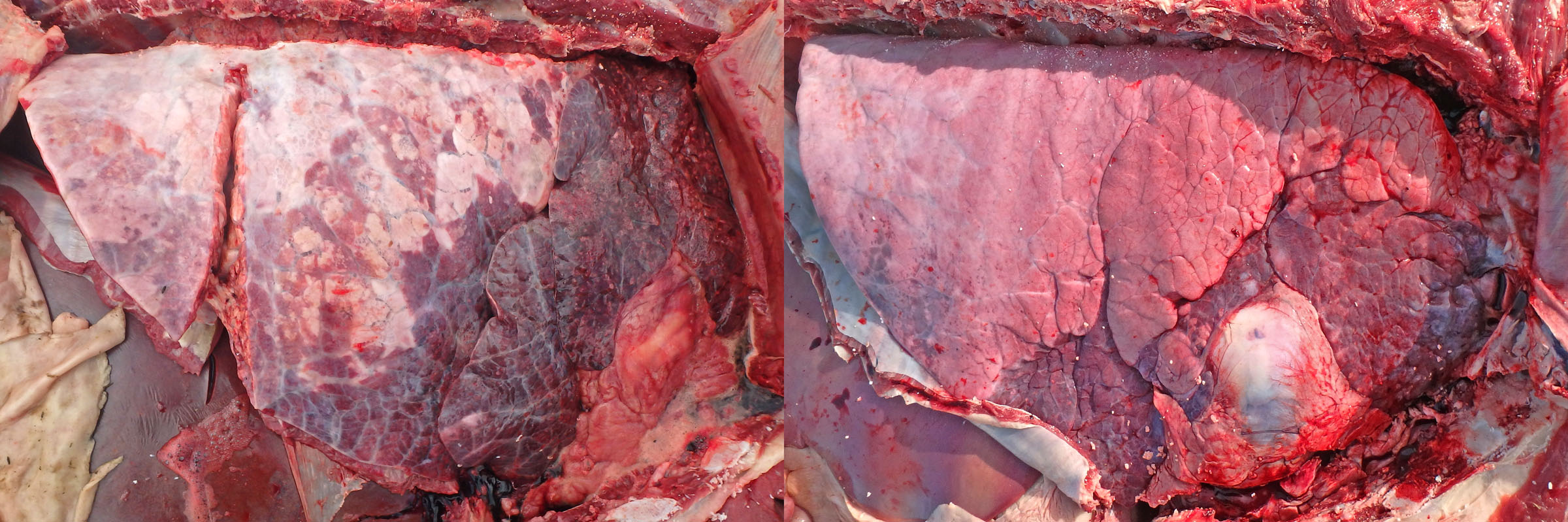

Morphology. The gross lesions typical of shipping fever are a cranioventral lobar or lobular pattern of consolidation and reddening, as a result of fibrinopurulent exudate in the alveoli (making them palpably hard). In addition, peracute or acute cases often have:

- Hemorrhagic purple-black lobules, giving a red/tan checkerboard pattern

- Loosely adherent fibrinous exudate on the pleural surface

- Interlobular septa distended by edema and fibrin

- Foci of necrosis visible on the cut surface, which appear as irregularly shaped pale foci surrounded by a rim of red (hemorrhage) or white (intense leukocyte infiltration).

In less severe or less fulminant cases, the lesions may be in a cranioventral lobular distribution, and consist of consolidation (firm red areas) without fibrinous exudate.

Chronic cases may develop tough fibrous adhesions on the pleura, abscessation of lung tissue, bronchiectasis, or sequestrum formation.

Diagnosis: Pneumonic pasteurellosis is by far the most common cause of respiratory signs in cattle, and the cranioventral and mostly symmetrical gross lesions are usually sufficient for diagnosis. Gross features that would lead to an alternative diagnosis include:

- Asymmetrical, unilateral or focal bronchopneumonia, especially with extensive necrosis and foul smell, can suggest aspiration pneumonia. Consider the recent clinical history for risk factors.

- Rubbery rather than firm/hard lesions in cranioventral lung may indicate viral pneumonia such as BRSV.

- The concurrent findings of cranioventral subacute bronchopneumonia and dorsocaudal acute interstitial pneumonia may explain acute exacerbation of clinical signs. “Bronchopneumonia with interstitial pneumonia” of feedlot cattle follows this pattern.

- Cranioventral bronchopneumonia with concurrent necrosis of tracheal epithelium suggests infectious bovine rhinotracheitis, with a fatal secondary bacterial pneumonia.

- Cranioventral bronchopneumonia in which the consolidated lung contains multifocal white circular crumbly foci of necrosis indicates Mycoplasma bovis.

- Consolidation affecting predominantly the caudal lobes could be caused by Dictyocaulus; open the caudal bronchi to carefully look for worms.

- Multifocal nodules in various regions of the lung suggest embolic pneumonia. Look in other organs for the source of infection.

- Diffusely firm and congested lungs that fail to collapse and have interlobular edema and emphysema suggest interstitial pneumonia. You need to slice the lung and carefully palpate individual lobules to convince yourself that the texture is firmer from normal collapsed lung.

- Diffuse pulmonary edema and congestion, with soft or slightly rubbery texture, should stimulate a careful examination of the heart for valvular endocarditis, Histophilus somni myocarditis, white muscle disease, or anomalies.

Bacterial culture is used if identification of the specific pathogen and its antimicrobial susceptibility is needed. Cultures are often negative if the animal has been treated with antibiotics, and the antimicrobial susceptibility of isolates from antiobiotic-treated animals should not be used to guide the selection of antibiotics for treatment of surviving herdmates.

Should you sample swabs or pieces of tissue for culture? Swabs allow precise sampling, and the transport medium supplied with the swab preserves the pathogen during shipment to the lab. However, contaminants are more likely, because of the impossibility of using aseptic technique in a field necropsy. Submitting a 2×2 cm piece of tissue for culture is the alternative, and contamination is less likely because laboratory technicians sear the surface before taking a culture of the deep tissue. However, it is more effort to bag tissue samples than to take a swab, and tissue samples are more prone to degradation during transport. We submit tissue samples from our postmortem room, but swabs are typically used by clinical vets doing field postmortems.

Cultures should be taken from the “leading edge” of the lesion (the area of diseased cranioventral tissue that is close to the more normal dorsocaudal lung), because the older lesion in the most severely affected part of the lung may be secondarily colonized by other bacteria (e.g. Trueperella pyogenes). But be sure to take the sample from tissue with lesions, and not from normal tissue.

Sequelae: Animals may die acutely due to sepsis or “toxemia”, and often not due to respiratory failure per se. Chronic sequelae include chronic bronchopneumonia, abscessation, sequestrum formation, bronchiectasis, and pleural adhesions. Relapses following apparently successful treatment often occur because these chronic lesions are a persistent source of infection that resists antibiotic treatment.

Question:

What are the three related bacteria that commonly cause bronchopneumonia in cattle? (Answers are provided at the end of the chapter).

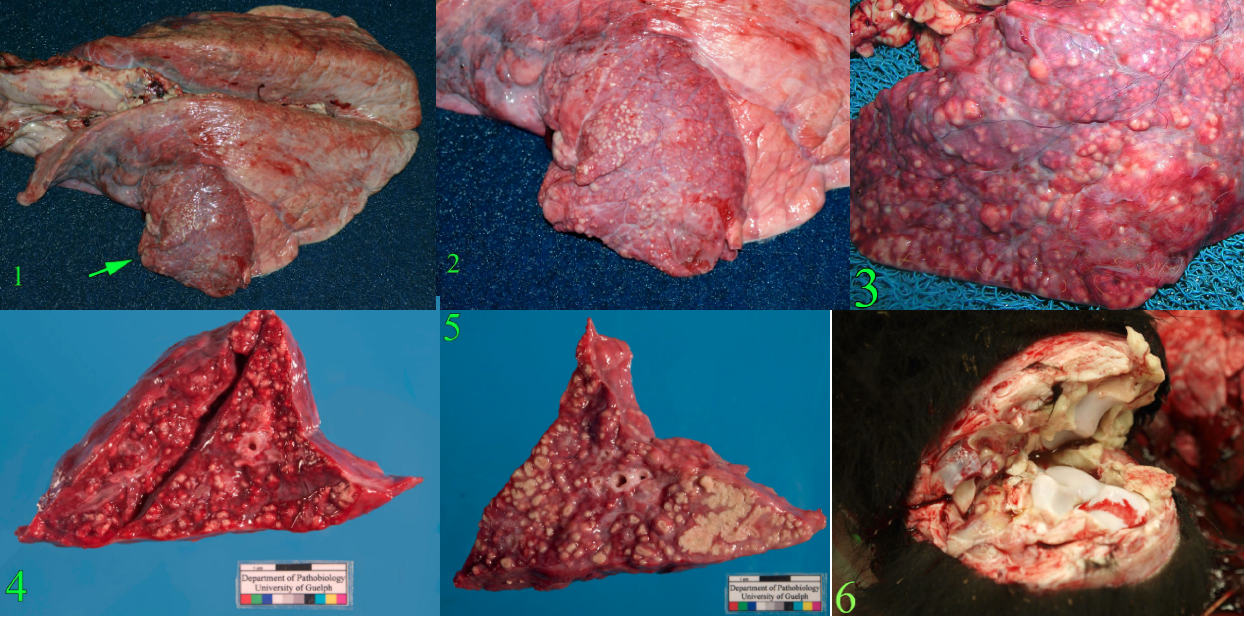

Mycoplasma bovis

Mycoplasma bovis causes “chronic pneumonia and polyarthritis syndrome”, often in conjunction with other pathogens. The condition in feedlot cattle appears in the second month after arrival in feedlots in contrast to the usual development of pneumonic pasteurellosis in the first few weeks.

In situations where animals from different sources are co-mingled, such as feedlots and veal barns, most calves are infected with M. bovis even though few develop disease. The evidence suggests that M. bovis by itself may cause minimal or only mild disease, but that it can worsen or perpetuate disease in animals with other lung infections. For example, M. bovis-induced pneumonia is worse with concurrent bovine herpesvirus 1 infection, and M. bovis seems to colonize the lung lesions caused by Mannheimia haemolytica, so these calves develop chronic mycoplasmal pneumonia even if the Mannheimia is cleared by antibiotic treatment or the calf’s immune response. BVDV infection predisposes to both pneumonic pasteurellosis and M. bovis pneumonia but doesn’t appear to play a direct role in the pathogenesis of this disease.

The characteristic lesions are termed “caseonecrotic bronchopneumonia”: cranioventral bronchopneumonia in which the consolidated areas contain multiple, circular, white, raised, friable foci of caseous necrosis. In contrast, the foci of coagulation necrosis caused by Mannheimia are irregularly shaped, red, non-raised, and not friable.

Mycoplasma bovis also spreads from the nasopharynx via the auditory tube into the middle ear to cause otitis media with droopy ears or head tilt, or blood-borne spread to the joints to cause fibrinopurulent polyarthritis and tenosynovitis with chronic lameness, or cow-to-cow transmission via the teat canal to cause mastitis.

Question:

What pathogen causes caseonecrotic bronchopneumonia with polyarthritis in cattle? (Answers are provided at the end of the chapter).

Aspiration pneumonia

Major reasons for aspiration pneumonia in cattle include:

- Force-fed milk replacer, liquid medicines, misplaced esophageal tube.

- Cleft palate. Be sure to look for this in young animals with pneumonia.

- Recumbency: milk fever or mastitis.

Grossly, this may appear as a cranioventral area of consolidation similar to other forms of bronchopneumonia. However, the characteristic features to suggest aspiration pneumonia are a localized or unilateral lesion, which is often foul-smelling and necrotic/friable due to anaerobic bacterial infection.

Viral pneumonia

Viral infections, along with stressors, are the major risk factors for bacterial pneumonia in cattle.

Primary viral pneumonia also occurs, in which bacterial infection plays little or no role. Primary viral pneumonia can present as an outbreak, whereas endemic disease is more likely to also involve bacteria. Viral pneumonia is most common in young calves, occasionally occurs in feedlot cattle soon after arrival, and is uncommon in adult cows. Important predisposing factors are introductions of new animals from a different source, inadequate ventilation and poor air quality, and crowding. These factors promote the spread of pathogens, as well as the health of the respiratory mucosa.

Causes:

- Bovine respiratory syncytial virus

- Bovine herpesvirus-1

- Bovine coronavirus

- Bovine parainfluenza virus

BRSV causes primary viral pneumonia, and can also predispose to bacterial pneumonia. Bovine herpesvirus causes infectious bovine rhinotracheitis, which is mainly an upper respiratory disease, but like BRSV this virus also predispose to bacterial pneumonia. Bovine viral diarrhea virus is an important predisposing cause of bacterial bronchopneumonia, but does not cause respiratory disease by itself. Bovine coronavirus is a very common viral infection; in addition to enteric disease, it probably also causes respiratory disease but this is somewhat controversial. Influenza D virus has received much recent attention but its role in disease is not yet clear.

Morphology: Grossly, BRSV usually causes a cranioventral lobular pattern of atelectasis with rubbery texture, but not as firm or consolidated as is typical of bronchopneumonia. Dorsocaudal lobes are often emphysematous and rubbery. So, the entire lung has firmer texture than normal, with collapse of cranioventral lung and crepitus of the dorsocaudal area.

Secondary cranioventral bronchopneumonia may also be present, as these viruses impair mucociliary clearance and alveolar macrophage function.

Diagnosis:

On dead animals: Histologic lesions of bronchiolar necrosis and alveolar hyaline membranes or type II pneumocyte proliferation suggest viral infection, and cases that die soon after infection may show syncytia in bronchioles that indicate BRSV. Confirmation involves demonstrating virus in frozen tissue using PCR testing, or in fixed tissue using immunohistochemistry.

On live animals: Virus can be identified in nasal swabs using PCR, antigen-detection assays, or virus isolation. These methods can provide a rapid diagnosis of the cause of the respiratory disease. It is important to recognize, for most respiratory viruses in all species, that the virus is cleared within 4-7 days of infection, and this corresponds to the first 1-4 days of clinical signs. Samples taken after this time will not contain viral antigen or nucleic acid, no matter what test method is used. Therefore, to detect viral antigen/nucleic acid, samples must be taken in the first 3-4 days of the outbreak from calves in the early stages (1-2 days) of disease. If you are not called to the farm until after this stage of disease, it may be impossible to detect viral antigen/nucleic acid in samples from live animals or dead animals.

Serology is an alternative testing strategy in the above situation. Serum antibody titres are measured in samples taken during acute disease and three weeks later. Measuring titres in a single serum sample is of no value. Serology is a very sensitive method to identify the cause of the outbreak, and rising titres can be detected even if you are called late to the farm. The disadvantage of serology is that the diagnosis is not made until the outbreak is long past, and it can be costly if large numbers of animals are tested.

INFECTIOUS BOVINE RHINOTRACHEITIS

Bovine herpesvirus-1 (BHV-1) was mentioned above with viral pneumonia, but it causes a “special” disease: infectious bovine rhinotracheitis (IBR). Note that BHV-1 may also cause other disease conditions: systemic disease in neonates, or encephalitis, or abortion.

IBR causes an acute onset of fever, depression, and variable degree of dyspnea, and careful inspection of the nasal cavity may reveal erosions. Most deaths from IBR result from secondary bacterial bronchopneumonia.

Gross lesions are erosions of nasal, laryngeal and tracheal mucosa, which appears either as tiny white depressed foci, or more commonly as a white mat of fibrin and necrotic tissue that sticks to the tracheal mucosa. This material cannot be easily wiped off of the mucosa, in contrast to the expectorated material that can be easily removed from the tracheal mucosa in cases of bacterial bronchopneumonia. Note that IBR causes necrosis in the respiratory tract (nasal, larynx, trachea), whereas BVD-mucosal disease causes necrosis in the digestive tract (oral, esophagus, intestine).

Diagnosis is as described for viral pneumonia: PCR testing or immunohistochemistry on lung tissue from dead animals, or for live animals testing of nasal swabs or serology.

Toxic lung disease

Toxic lung injury is rare in domestic animals, but important to recognize because many animals are usually affected.

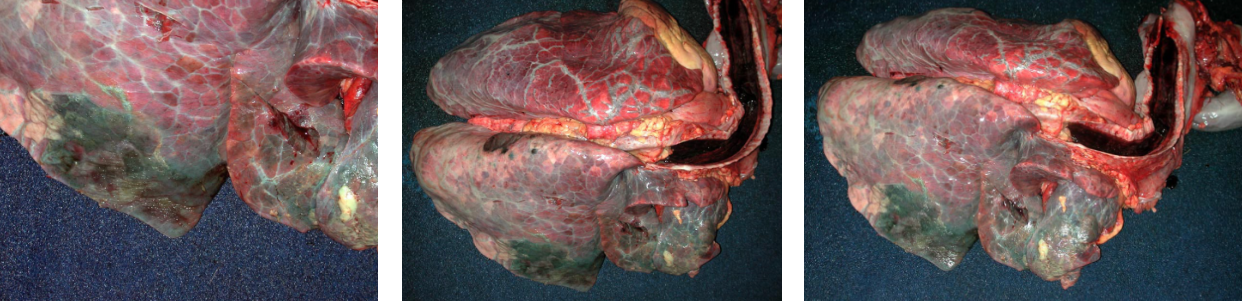

3-Methylindole toxicity (acute bovine pulmonary edema and emphysema, “fog fever”) affects adult cattle given sudden access to lush pastures. Affected cows have an acute onset of severe dyspnea, and death if forced to exercise. This disease is now uncommon, but it is a classic example of how an ingested toxicant causes lung disease. Lush pastures contain tryptophan, which is metabolized by rumen microbes to 3-methylindole (3-MI). The toxin is absorbed from the rumen, and delivered by the blood to the lung. Club cells and type II pneumocytes convert 3-MI to a reactive intermediate in the process of detoxification. This reactive compound is thought to cause oxidative injury to alveolar and bronchiolar epithelium, resulting in interstitial lung disease. This process is analogous to periacinar hepatic necrosis caused by conversion of hepatotoxins to reactive intermediates. Morphology: Gross lesions are diffuse pulmonary edema, congestion, emphysema, and firm or rubbery texture. The lesions are generalized (affect all parts of the lung) but more obvious in the caudal lobes. Histologic lesions include alveolar edema and hyaline membranes.

More toxins that are activated by type II pneumocytes and/or club cells include ipomeanol (mouldy sweet potatoes), perilla ketones (purple mint), and paraquat (herbicide).

Other toxins need not be metabolized to reactive intermediates, and instead cause direct damage to the lung on inhalation. These include ammonia, hydrogen sulfide (manure pit gas), nitrogen dioxide (silo gas). These gases more commonly cause peracute death without lesions (e.g. when accidentally exposed to gases by agitation of manure pits), but interstitial pneumonia may develop in surviving animals.

Interstitial pneumonia of feedlot cattle

Commonly identified in southern Alberta feedlots, it does occur but seems less common in Ontario. Affected cattle have an acute onset of severe dyspnea and lesions of diffuse interstitial pneumonia similar to that described for 3-methylindole toxicity (see below). Lesions are present throughout the lung, more evident in caudal lobes, and may be either diffuse or have a so-called checkerboard pattern where some lobules are affected more than others. The cause is not clear but appears to be related to the feed.

Dictyocaulus viviparus

Lungworms are most common in cool, wet climates. This is an uncommon diagnosis in Ontario but cases definitely do occur and it is suspected than many are missed by veterinarians. This is an important diagnosis because multiple animals are usually affected, and disease control is very different than for other respiratory pathogens.

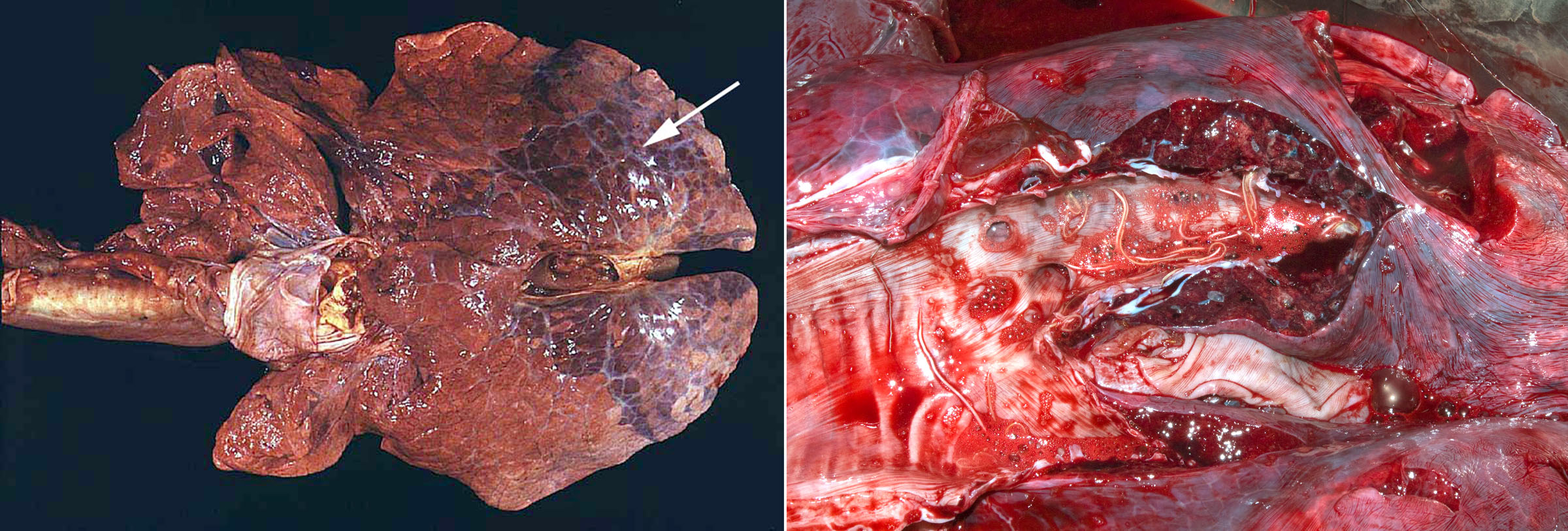

Adults worms are grossly visible, thread-like, white nematodes in bronchi within caudal lobes. These are easily overlooked if the caudal bronchi are not opened. When opening the trachea and bronchi at necropsy, always continue to the caudal bronchi: it takes an extra 15 seconds, and can lead you to an obvious and impactful diagnosis.

There are three distinct manifestations of lungworm in cattle:

- Acute diffuse interstitial pneumonia in naive calves exposed to pastures that are contaminated with many larvae. The disease is so acute that there are not yet any adults in the bronchi or larvae in feces. The diagnosis depends on histologic detection of larvae in formalin-fixed sections of lung.

- Chronic patent infections with adults in bronchi and larvae in feces causing acute or chronic respiratory disease. This is the most common disease manifestation. The diagnosis is usually made by detecting larvae in feces of live animals (Baermann test) or by seeing worms in the caudal bronchi of animals that have died.

- “Reinfection syndrome”: sensitized adult animals that are re-infected with large numbers of larvae may develop acute interstitial pneumonia, but the partial immune response doesn’t allow patency. There are no adults in the bronchi and no larvae in feces. This is the least common disease manifestation.The diagnosis depends on histologic detection of larvae in the multifocal nodular lung lesions.

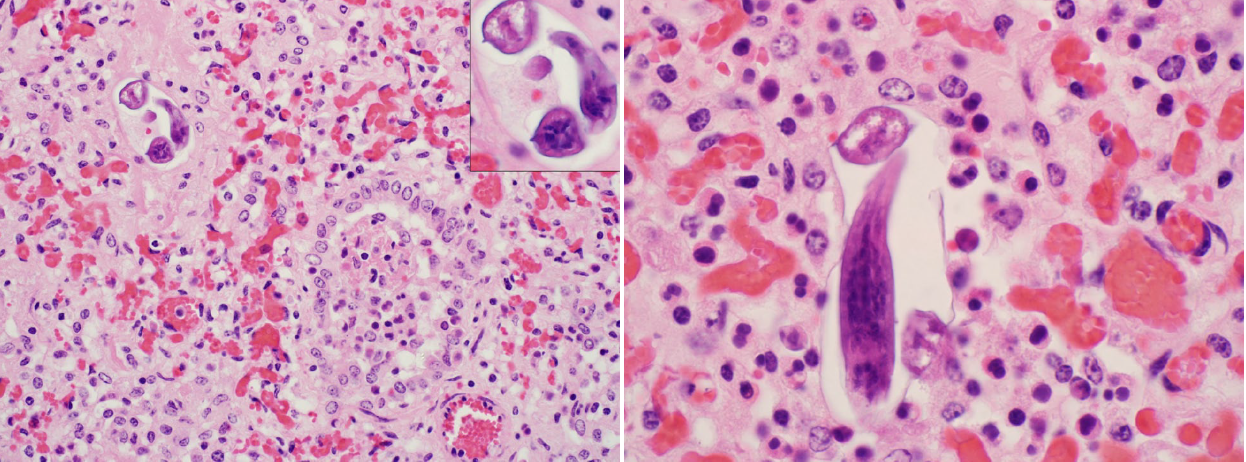

Ascaris suum larval migration

Ascaris suum is the intestinal roundworm of pigs, and the larva migrates through liver and lung, before returning to the intestine where it matures to adulthood. This disease occurs in calves raised in barns that formerly housed swine. Lesions are diffuse interstitial pneumonia, which are histologically characterized by numerous eosinophils and rare larvae. You probably wouldn’t think of this disease clinically, but the diagnosis can be made histologically by observing the wandering larvae. It’s an uncommon disease but is seen regularly in Ontario, and illustrates the value of laboratory testing for mysterious cases.

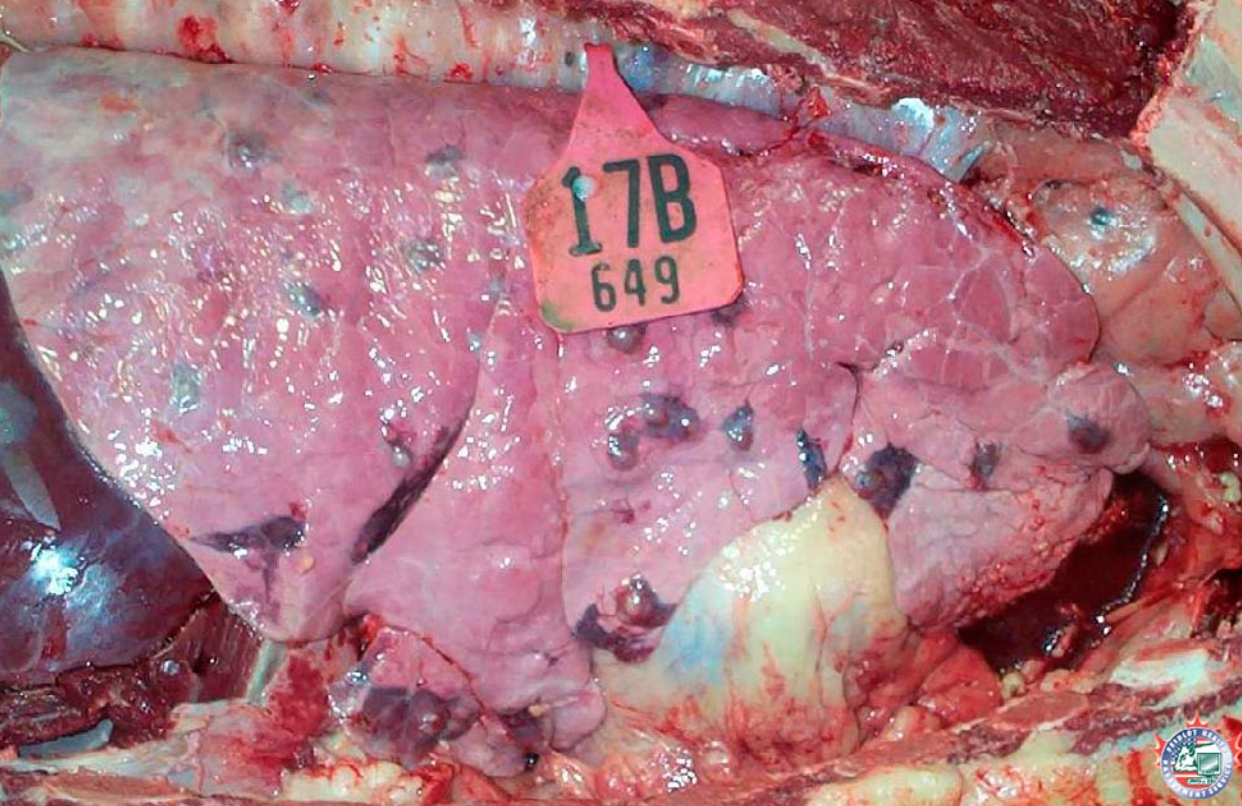

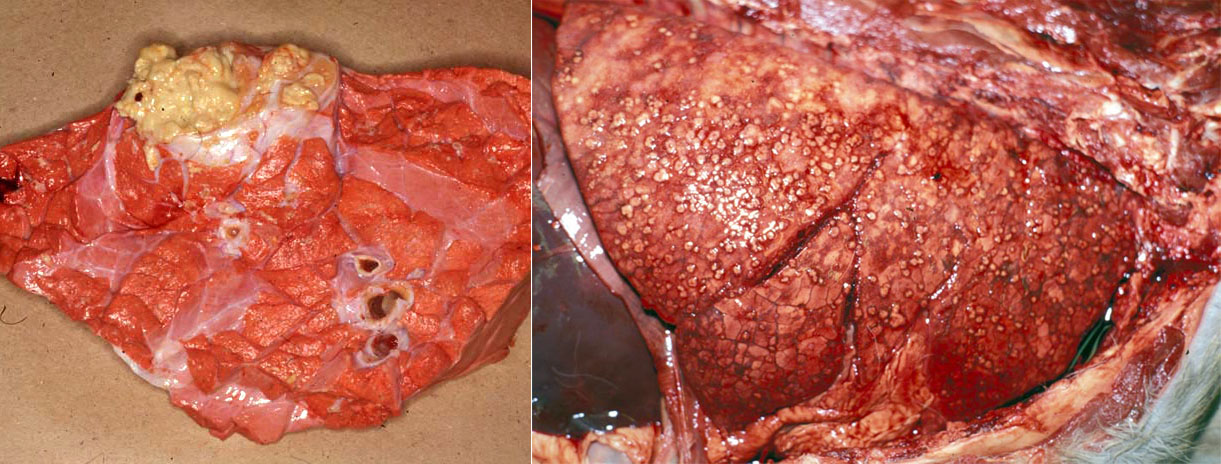

Embolism from liver abscess

Caval syndrome occurs when a thrombus obstructs the caudal vena cava, which leads to ascites from backup of venous pressure. For this reason, you must routinely open the caudal vena cava between the heart and the liver/diaphragm on every feedlot postmortem case.

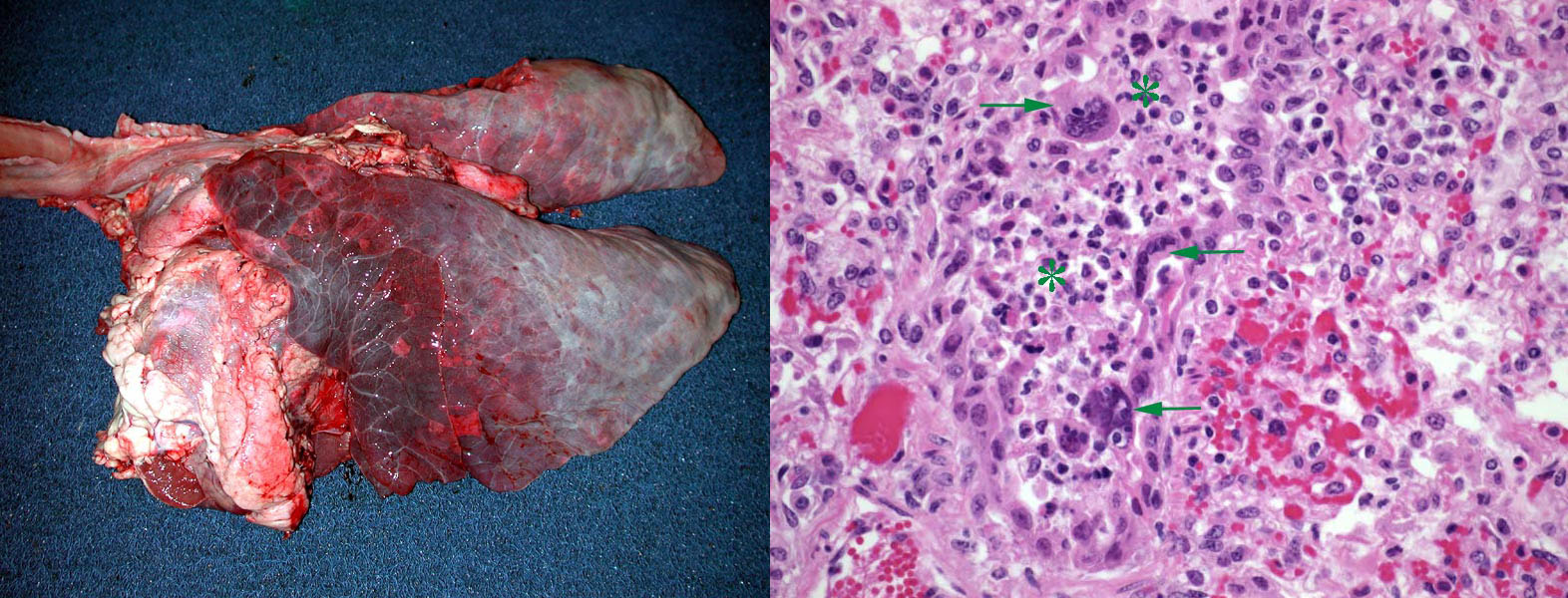

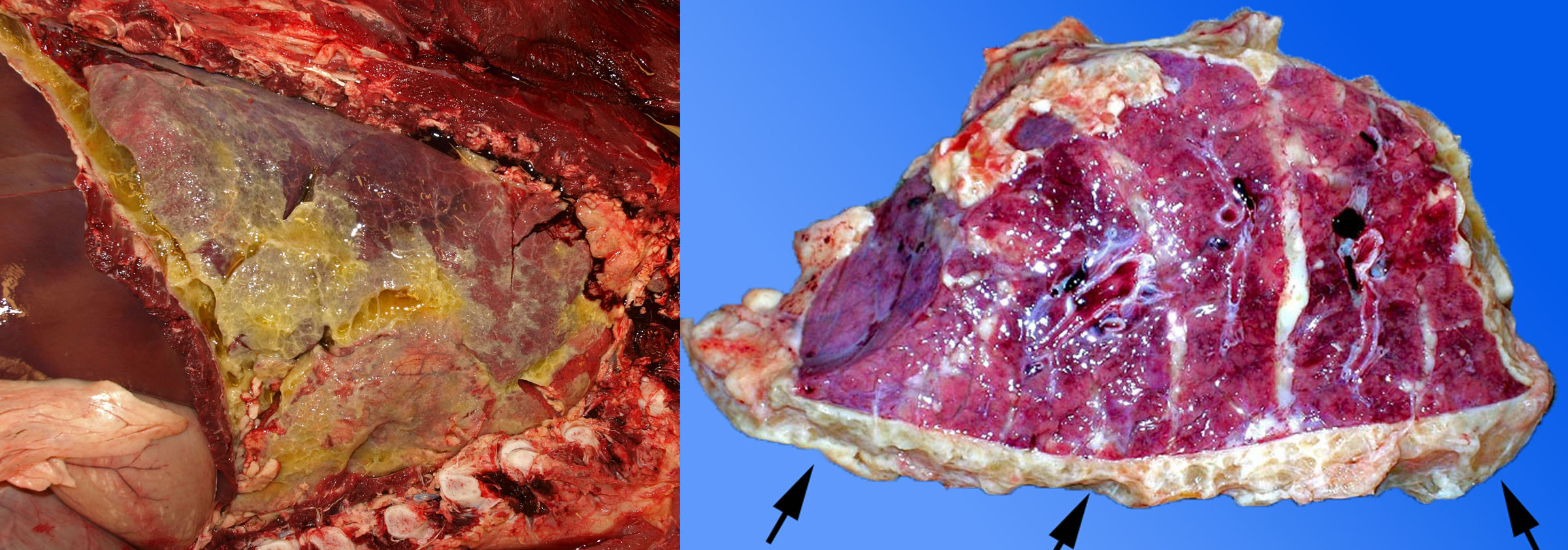

Fibrinous pleuritis caused by Histophilus somni

Histophilus somni can cause bacteremia, with localization of the blood-borne bacteria on serosal surfaces: the pleura, pericardium, joints, and sometimes peritoneum. With H. somni, this characteristically induces inflammation with abundant fibrin, so that one or more of these body cavities are filled with fibrin and clear fluid. In feedlot cattle, observing serofibrinous pleuritis without involvement of the underlying lung tissue is sufficient for routine diagnosis of H. somni pleuritis. Definitive diagnosis is by culturing a swab of the exudate in the pleural cavity.

Note that this disease — fibrinous pleuritis due to hematogenous spread of H. somni with no involvement of the lung tissue (no bronchopneumonia) — is quite different from fibrinous pleuritis secondary to extension from cranioventral bronchopneumonia. In the latter disease, bacteria enter the lung via the airways to cause bronchopneumonia, and in some of these cases there is spread of bacteria across the pleura to cause “pleuropneumonia” or bronchopneumonia with secondary pleuritis. This could be caused by H. somni, M. haemolytica or other bacteria.

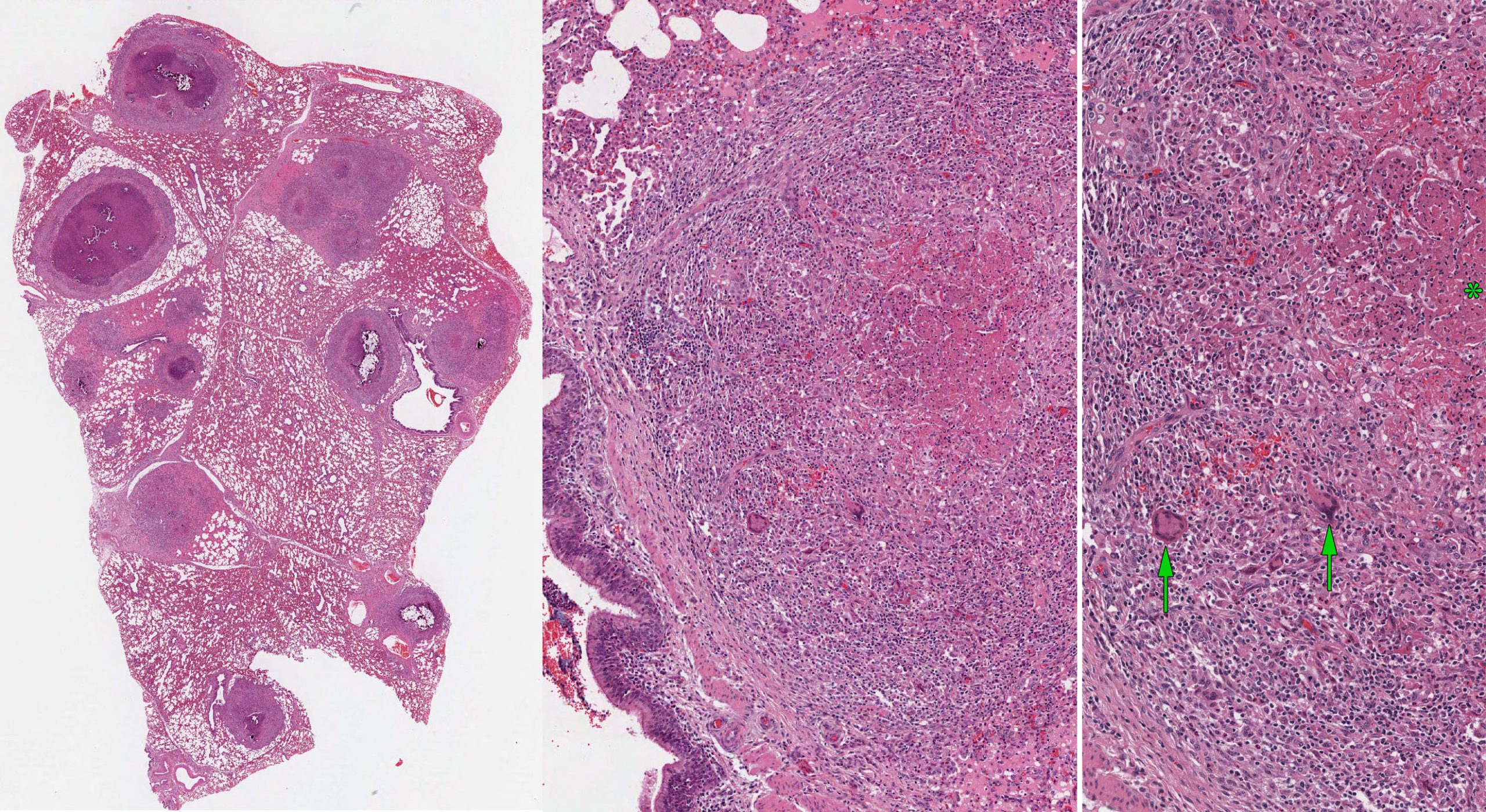

Bovine tuberculosis

Mycobacterium bovis causes bovine tuberculosis, and occasionally causes disease in humans. Most human cases are oropharyngeal or enteric infections due to ingestion of contaminated, non-pasteurized milk. The vast majority of human tuberculosis cases are caused by Mycobacterium tuberculosis, and infected humans sometimes transmit infection to their cats and dogs, but M. tuberculosis infection is rare in cattle.

Bovine tuberculosis is an immediately notifiable (reportable) disease in most developed countries including Canada. Although the prevalence is low enough that Canada is considered officially free of the disease, cases do occur occasionally in Canada, and these are usually first detected by clinical veterinarians or meat inspectors. So, it important to know about this disease, because of your role in early detection of cases before infection is transmitted to other herds and eradication becomes much more difficult.

Pathogenesis: Bacilli are phagocytosed by macrophages, but the complex cell wall lipids—which give the bacteria their acid-fast staining quality—prevent killing by non-activated macrophages. An adequate cell-mediated immune response enables T lymphocytes to activate macrophages to kill the pathogen. Most chronically infected animals do not show clinical signs, even though they can intermittently shed bacteria in sputum and are thus a source of infection to other animals and to other herds.

Gross lesions are caseating tubercles in retropharyngeal and tracheobronchial lymph nodes and in lung. The tubercles consist of a focal area of caseous necrosis, often with mineralization, and usually with a fibrous capsule. Many cases have only one lesion in the lung or lymph node, yet it is critical to detect these subclinical cases because they can transmit infection to herd mates. Other cases have multiple caseating nodules throughout the lung. Lesions may erode through the pleura and cause multiple tiny nodules on pleural surfaces, or erode blood vessels to cause disseminated small granulomas (miliary tuberculosis) or larger granulomas in multiple organs.

Lesions in farmed cervids (deer and elk) are often suppurative and can resemble abscesses.

Diagnosis: As this is an immediately notifiable disease, diagnostic testing in Canada is done by CFIA. This involves intradermal skin testing of affected and in-contact animals, as well as testing of lung and lymph nodes of euthanized animals using special mycobacterial culture as well as acid-fast stains of histologic sections.

Question:

List two causes or diseases resulting in diffuse interstitial pneumonia in cattle. (Answers are provided at the end of the chapter).

Question:

What are the two reportable (immediately notifiable) lung diseases of cattle? (Answers are provided at the end of the chapter).

Question:

List three different lung lesions resulting from liver abscesses. (Answers are provided at the end of the chapter).

Question:

What is the specific location of Dictyocaulus viviparus in adults? (Answers are provided at the end of the chapter).

Miscellaneous conditions

- Pulmonary edema. Clinical signs of respiratory distress need not be caused by respiratory disease. Heart disease can cause clinical signs that resemble pneumonia. Sporadic causes include valvular endocarditis, Histophilus somni myocarditis, and congenital anomalies such as ventricular septal defect. Multiple animals can develop respiratory signs in cases of myocardial necrosis caused by white muscle disease or feed-related toxicity such as monensin.

- Honker syndrome: tracheal edema and hemorrhage syndrome. Affected feedlot cattle develop an acute onset of dyspnea with stridor (honking inspiratory dyspnea) due to marked edema and/or hemorrhage of the tracheal mucosa that partially obstructs the lumen. The cause is not known.

- Necrotic laryngitis (laryngeal necrobacillosis). Ulcers of the larynx are thought to develop from the trauma of the larynx crashing shut, in feedlot cattle with rapid heavy breathing from pneumonia. The ulcers are often secondarily infected with Fusobacterium necrophorum, and typically respond well to antibiotic treatment. This disease of older calves should not be confused with “diphtheria” or oral necrobacillosis of young calves, which causes extensive necrotizing lesions of the oropharynx, and occasionally involves larynx and trachea.

- Contagious bovine pleuropneumonia. Caused by Mycoplasma mycoides ssp. mycoides, it is of major importance for livestock production in Africa, and is an immediately notifiable (reportable) disease.

- Allergic alveolitis or hypersensitivity pneumonitis. This is a hypersensitivity to inhaled spores of the mold Micropolysporum faeni, resulting in chronic coughing or dyspnea, and is most common in housed cows in wet climates.

- Meconium aspiration syndrome in neonates. Aspiration of meconium during dystocia incites an inflammatory reaction in the neonatal calf.

Septicemic lung injury. Neonatal calves with septicemia may have diffusely edematous and firm lungs, representing interstitial lung disease.

Question:

Describe the gross lesions resulting from respiratory infection with bovine herpesvirus-1. (Answers are provided at the end of the chapter).

Question:

Describe the two different manifestations of Histophilus somni infection in the respiratory tract of feedlot cattle. (Answers are provided at the end of the chapter).

Question:

What disease causes erosions in the nasal cavity and trachea?

What disease causes erosions in the oral cavity and esophagus?

(Answers are provided at the end of the chapter).

Question:

What is the most likely specific cause of single focal soft white nodules in the dorsocaudal lung and bronchial lymph node of a cow? (Answers are provided at the end of the chapter).

Question:

Describe the pathogenesis of 3-methylindole toxicity in cattle. (Answers are provided at the end of the chapter).

Question:

What is one cause and one gross lesion of cor pulmonale in cattle? (Answers are provided at the end of the chapter).

Question:

In a cow with multiple foci of suppurative inflammation distributed throughout the lung, what is an underlying lesion in another organ? (Answers are provided at the end of the chapter).

Answer:

What are the three related bacteria that commonly cause bronchopneumonia in cattle?

Mannheimia haemolytica,

Bibersteinia trehalosi,

Histophilus somni,

Pasteurella multocida.

Answer:

What pathogen causes caseonecrotic bronchopneumonia with polyarthritis in cattle?

Mycoplasma bovis.

Histophilus somni causes polyarthritis and bronchopneumonia, without foci of caseous necrosis.

Answer:

List two causes or diseases resulting in diffuse interstitial pneumonia in cattle.

- Idiopathic interstitial pneumonia, feedlot cattle.

- Toxic lung disease such as 3-methylindole in pastured cattle (fog fever).

- BRSV.

- Endotoxemia or septicemia.

- Larval migration (Dicytocaulus, Ascaris).

Answer:

What are the two reportable (immediately notifiable) lung diseases of cattle?

Bovine tuberculosis.

Contagious bovine pleuropneumonia.

Answer:

List three different lung lesions resulting from liver abscesses.

- Embolic pneumonia with multiple lung abscesses

- Acute diffuse interstitial pneumonia

- Pulmonary embolism: thrombi filling pulmonary arteries.

Answer:

What is the specific location of Dictyocaulus viviparus in adults?

Bronchial lumen, in caudal lobes.

Answer:

Describe the gross lesions resulting from respiratory infection with bovine herpesvirus-1.

Fibrinous and erosive rhinotracheitis.

Answer:

Describe the two different manifestations of Histophilus somni infection in the respiratory tract of feedlot cattle.

Cranioventral bronchopneumonia, fibrinous pleuritis.

Answer:

What disease causes erosions in the nasal cavity and trachea?

What disease causes erosions in the oral cavity and esophagus?

IBR (BHV-1) causes respiratory lesions. BVDV causes lesions of the digestive system. The exception is systemic BHV-1 infection (only in calves <2 months old), which can include esophageal and rumental lesions).

Answer:

What is the most likely specific cause of single focal soft white nodules in the dorsocaudal lung and bronchial lymph node of a cow?

Mycobacterium bovis (bovine tuberculosis). Lung cancer could cause this lesion in dogs and cats but is so rare in cattle that you will never see a case.

Answer:

Describe the pathogenesis of 3-methylindole toxicity in cattle.

Tryptophan in feed is converted by rumen microbes to 3-methylindole, which is converted by type II pneumocytes to reactive intermediates that cause lung injury.

Answer:

What is one cause and one gross lesion of cor pulmonale in cattle?

Cause: high altitude, viral airway injury (bronchiolitis obliterans), pulmonary embolism …

Lesions: ascites, right ventricular hypertrophy, muscular hypertrophy of pulmonary arteries …

Answer:

In a cow with multiple foci of suppurative inflammation distributed throughout the lung, what is an underlying lesion in another organ?

Endocarditis, jugular thrombophlebitis, liver abscesses, …