Head and Neck Anatomy (Part B)

Salivary Glands of Head and Neck

The salivary glands produce saliva, which lubricates and cleanses the oral cavity and aids in the digestion of food through an enzymatic process. Saliva also helps maintain the integrity of tooth surfaces through a process of remineralization. In addition, saliva forms dental plaque and supplies minerals for supragingival calculus to form.

Salivary glands produce two types of saliva:

- Serous saliva is watery, mainly protein fluid.

- Mucous saliva is very thick, mainly carbohydrate fluid.

Salivary glands are classified by their size as either major or minor.

Minor Salivary Glands

The minor salivary glands are smaller and more numerous than the major salivary glands. The minor glands are scattered in the tissues of the buccal, labial, and lingual mucosa, the soft palate, the lateral portions of the hard palate, and the floor of the mouth.

Von Ebner’s salivary gland is associated with the large circumvallate papillae on the tongue.

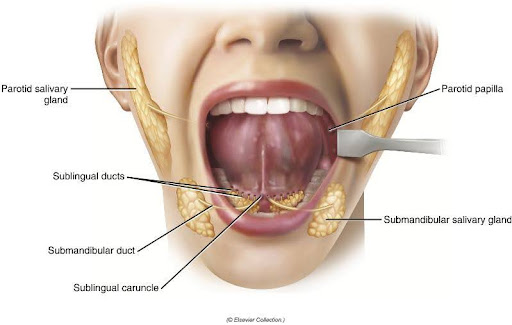

The three large paired salivary glands are the parotid, submandibular and sublingual glands.

The parotid salivary gland is the largest of these glands. It provides only 25% of the total volume of saliva. It is located in the area just below and in front of the ear. Saliva passes from the parotid gland into the mouth through a duct called the parotid duct (also known as Stensen’s duct).

The submandibular salivary gland is about the size of a walnut and is the second largest gland. It provides 60 to 65% of the total volume of saliva. It is located beneath the mandible in the submandibular fossa, posterior to the sublingual salivary gland. It releases saliva into the oral cavity through the submandibular duct (also known as Wharton’s duct), which ends in the sublingual caruncles.

The sublingual salivary gland is the smallest of the major glands. It provides only 10% of the total volume of saliva. It releases saliva into the oral cavity through the sublingual duct (also known as Bartholin’s duct).

Activity 1: Salivary Glands

Lymphatics of the Head and Neck

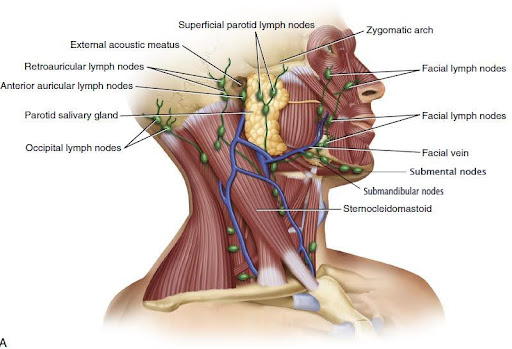

Lymph nodes are bean-shaped organs distributed throughout the head and neck, where they process lymph, or tissue fluid, that flows through the lymph vessels. Some are located close to the body surface, making them easy to palpate. Others are deeper, and others still are so deep that they cannot be palpated.

Inflammation of a lymph node, a condition called lymphadenopathy, indicates that there may be an infection or other disease nearby. Lymph nodes are impossible to detect on palpation when healthy. In the presence of disease, white blood cells within the node multiply and enlarge, causing the nodes, in turn, to enlarge and become tender to the touch.

You may have had a sore throat, and the lymph nodes in your neck may have become painful. Most often people refer to this as having “swollen glands“.

Cancer cells can travel within the lymph system to distant sites within the body, a process called lymphatic spread. Lymph nodes that are very hard and attached firmly to adjacent tissues (so they cannot be moved) are at risk for harboring cancer cells.

Specific Lymph Nodes of the Head and Neck

It’s important to palpate the following superficial lymph nodes during an extraoral examination:

- Occipital – back of the head, near the neck

- Retroauricular – behind the ear

- Anterior auricular – in front of the ear

- Superficial parotid – in the zygomatic region

- Facial – located along the facial artery/vein

- Submandibular – beneath the inferior border of the mandible

- Submental – beneath the chin

By palpating the lymph nodes at each dental examination, the dentist can establish the patient’s baseline, against which future findings may be compared, making detecting changes easier.

When someone has an infection or cancer in a region, the lymph nodes in that region will respond by increasing in size and becoming firm. This change in size and consistency is called lymphadenopathy.

Palpating Lymph Nodes of the Head and Neck

When checking lymph nodes use three fingers (index, middle and ring fingers) and gently palpate in the areas indicated by the images below:

|

|

| Checking submental nodes | Checking facial nodes |

|

|

| Checking retroauricular nodes | Checking occipital nodes |

The Paranasal Sinuses

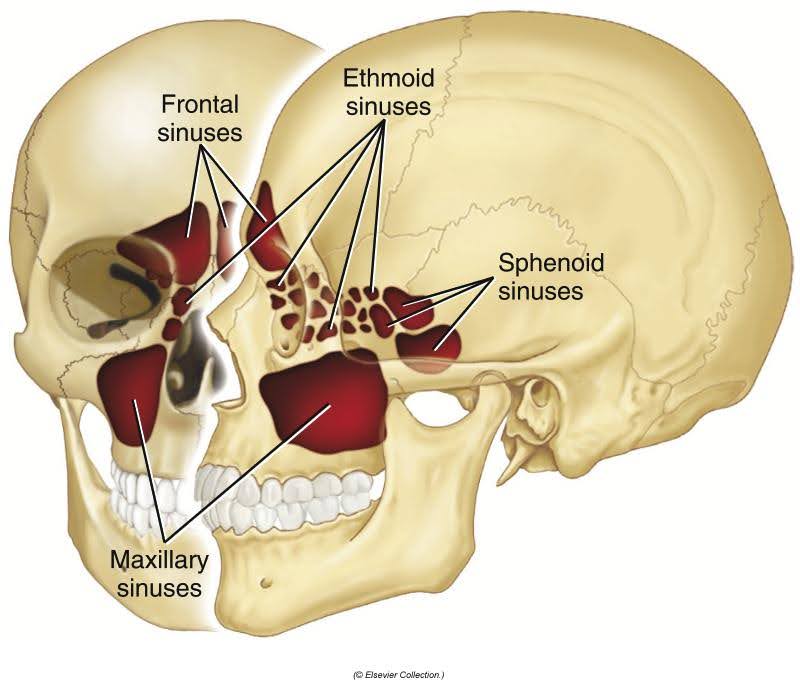

The paranasal sinuses are air-containing spaces within the skull that communicate with the nasal cavity. A sinus is an air-filled cavity within a bone.

The functions of the sinuses include:

- Producing mucus

- Making the bones of the skull lighter

- Providing resonance that helps produce sound

The maxillary teeth’ roots lie close to the sinus floor. Because the teeth and the maxillary sinus share a common nerve supply, sinus inflammation may cause a generalized aching of the maxillary teeth.

The sinuses are named for the bones in which they are located:

- Maxillary sinuses are the largest of the paranasal sinuses.

- Frontal sinuses are located within the forehead, just above both eyes.

- Ethmoid sinuses are irregularly shaped air cells separated from the orbital cavity by a very thin layer of bone.

Sphenoid sinuses are located close to the optic nerves, where an infection may damage vision.

Activity 2: Lymph Nodes

You have completed Module 4B. Please return to Blackboard for the next steps.

Media Attributions

- Images from: Modern Dental Assisting, 13th and 14th Edition

Region of the head pertaining to or located near the mouth.

Region of the head that refers to structures closest to the inner cheek.

Toward or from the side.

(FOS-ah, FAW-seh); Hollow, grooved, or depressed area in a bone.

Toward the back.

Closer to the bodies core.

Region of the head overlying the occipital bone and covered by the scalp.

Toward the front.

Region of the head pertaining to or located near the zygomatic bone (cheekbone).

Structures that are closer to the feet.

Region of the head pertaining to or located near the chin.