Head and Neck Anatomy (Part A)

The Muscular System

Muscles allow the body to move. When you’re surprised, your muscles enable you to raise and lower your mandible to chew food or raise the skin under your eyebrows. Both of these actions are performed by skeletal muscle under voluntary control.

This lesson will concentrate on two groups of muscles, the muscles of mastication and the muscles of facial expression. When learning about any muscle, it is important to remember the following four pieces of information:

- Origin – the structure (usually a bone) to which the muscle is attached; it doesn’t move.

- Insertion –the other, more movable point of attachment of a muscle; it may be bone, another muscle, or skin.

- Action – when stimulated, the muscle contracts pulling the movable insertion toward immovable origin.

- Innervation – the nervous stimulus that causes the muscle to contract.

The Muscles of Mastication

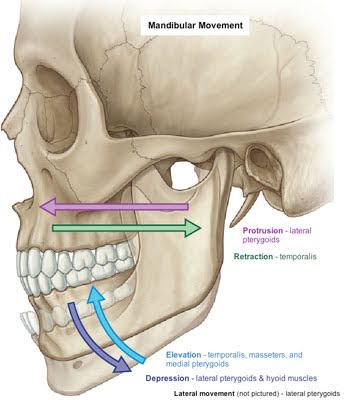

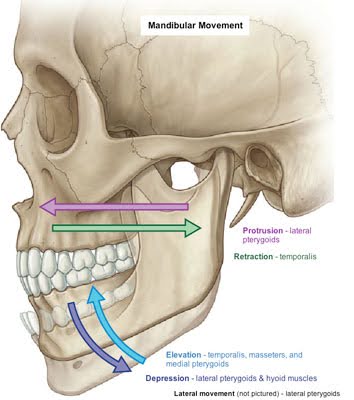

The mandible is the only movable bone of the skull. It is capable of five types of movement, thanks to the actions of the four paired muscles of mastication (chewing), as well as numerous lesser muscles. The five movements of the mandible are:

- Elevation – raising the mandible (i.e., closing the jaws)

- Depression – lowering the mandible (i.e., opening the jaws)

- Protrusion – moving the mandible forward

- Retraction – moving the mandible backward

- Lateral movement – moving the mandible from side to side

Innervation for all of the muscles of mastication is supplied by the fifth cranial nerve, also known as the trigeminal nerve.

Mastication of food requires tremendous force to close the jaws powerfully enough to crush food between the teeth. The elevator muscles are responsible for this mandibular motion; let’s look at those first.

Elevator Muscles

There are four muscles of mastication:

- Temporalis

- Masseter

- Medial pterygoid

- Lateral pterygoid

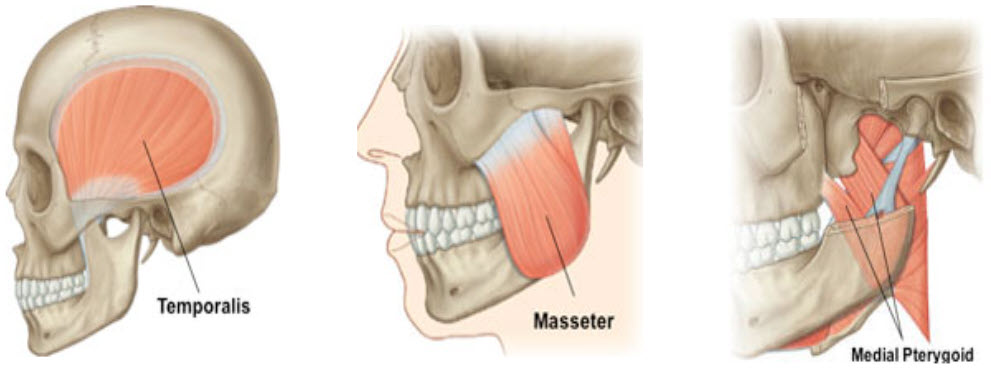

Three pairs of muscles cause mandibular elevation (closure). First up are the two fan-shaped temporalis muscles, each of which has its origin in the broad, shallow depression on the side of the skull called the temporal fossa. The temporalis muscle passes beneath the zygomatic arch and inserts onto the coronoid process of the mandible.

The masseter is a strong muscle that has its origin on the zygomatic arch and inserts onto the outer surface of the mandible at the ramus and angle.

Finally, the medial pterygoid muscle originates from the pterygoid processes of the sphenoid bone and inserts onto the inner surface of the mandible at an angle, forming a sling around the mandibular angle with the masseter.

Depressor Muscles

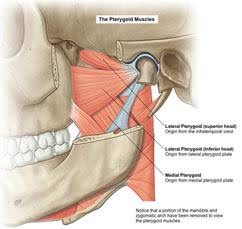

Lowering the jaw (depression) doesn’t require much muscle effort. Gravity plays a part, with an assist from both lateral pterygoid muscles. Simultaneous contraction of the lateral pterygoid muscles pulls the condyles forward in the TMJ. The joint’s anatomy causes the condyle to move forward and downward, resulting in mandibular depression.

The lateral pterygoid muscles, the fourth and final major muscles of mastication, have two origins: one from the lateral pterygoid plates of the sphenoid bone and the other from the infratemporal crest (refer to image). These two heads of the muscle converge to insert onto the neck of the condyle of the mandible.

Muscles attached to a free-floating bone in the neck, the hyoid bone, also play an important part in mandibular depression.

Protrusion, Retraction, and Lateral Movement Muscles

A protrusion is the action of jutting the lower jaw forward. This is accomplished with the bilateral contraction of the lateral pterygoid muscles without the action of the hyoid muscles we mentioned on the previous slide.

Retraction or retrusion of the mandible, which involves moving the mandible backward into a resting position, is accomplished by the bilateral contraction of the posterior fibers of the temporalis muscles.

Contraction of one lateral pterygoid muscle causes mandible movement to the opposite side. Mastication involves a combination of these five jaw movements.

Muscles of Facial Expression

The muscles of facial expression are very superficial, lying just beneath the skin. Unlike the muscles of mastication, these muscles don’t necessarily originate from bone, although most do. Most of these facial muscles insert into the skin, allowing them to cause the skin to fold when they contract.

The major muscles of facial expression are:

- Orbicularis oris

- Buccinator

- Mentalis

- Zygomatic major

Innervation for all the muscles of facial expression is supplied by the seventh cranial nerve, the facial nerve.

The orbicularis oris originates from the muscle fibers around the mouth; there is no skeletal attachment. It inserts into itself and the skin surrounding the muscle. The function of the orbicularis oris is to close and pucker lips. It also aids in speaking by pressing the lips against the teeth.

The buccinator originates from the posterior portion of the alveolar processes of the maxillary bone and the mandible. It inserts into the fibers of the orbicularis oris at the angle of the mouth. The function of the buccinator is to compress the cheeks against the teeth and retract the angle of the mouth.

The mentalis originates from the incisive fossa of the mandible and inserts into the skin of the chin. The mentalis wrinkles the skin of the chin and pushes up the lower lip.

The zygomatic major originates from the zygomatic bone and inserts into the fibers of the orbicularis oris. Its function is to draw the mouth upward and backward, as when laughing.

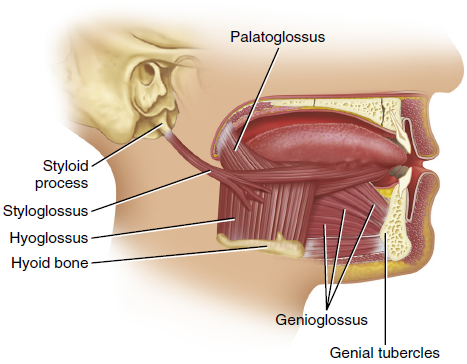

Muscles of the Tongue

The tongue is a very muscular organ. It contains intrinsic tongue muscles (located within the tongue itself) that assist in speaking, chewing, and swallowing. Extrinsic tongue muscles originate from external structures and insert into the tongue. The extrinsic tongue muscles include the:

- Genioglossus

- Hyoglossus

- Styloglossus

- Palatoglossus

All tongue muscles except the palatoglossus are innervated by the hypoglossal nerve. These muscles raise and lower the tongue, moving it forward and backward. Muscles of the tongue and the floor of the mouth attach to the hyoid bone.

Muscles of the Floor of the Mouth

The muscles of the floor of the mouth are:

- Digastric

- Mylohyoid

- Stylohyoid

- Geniohyoid

All these muscles are located between the mandible and the hyoid bone and are innervated by different nerve branches.

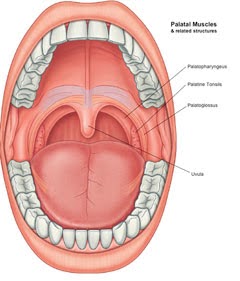

Palatal Muscles

The opening to the pharynx from the oral cavity is surrounded by two bands of muscles. These are called the pillars of the fauces, and between them on either side are the palatine tonsils. The two muscles that form the pillars are the palatoglossus (anterior pillar) and the palatopharyngeus (posterior pillar) muscles. When they contract, they close like a drawstring change purse and thus help separate the oral cavity from the pharynx during swallowing.

Neck Muscles

Two major muscles located in the neck assist in turning the head and shrugging the shoulders. They are the sternocleidomastoid muscle and the trapezius muscle. The sternocleidomastoid, a large strap muscle, is an important landmark in the extraoral examination of a patient.

Palpation of the sternocleidomastoid muscle is done by having the patient turn the head to the opposite side to help make the muscle stand out more, which is shown in the image below. The deep cervical lymph nodes are found around and deep in this muscle.

Activity 1: Muscles of Mastication

The Nervous System

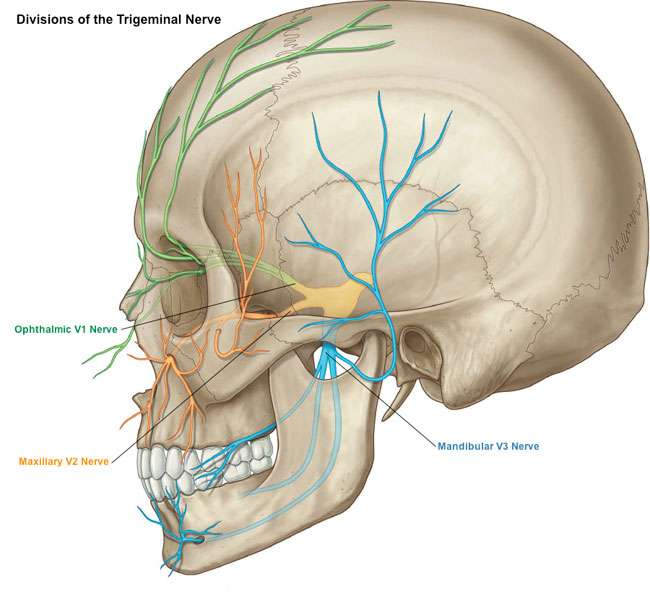

The structures of the head and neck receive their innervation mainly from the cranial nerves, 12 pairs of nerves that emerge from beneath the brain and exit the cranium through foramina to connect with muscles, glands, sense organs, and other structures in the head and neck. Two of the cranial nerves have particular relevance to oral and facial structures: the fifth (V) cranial nerve (trigeminal) and the seventh (VII) cranial nerve (facial). For the purposes of this discussion, we’ll simplify the division of labor for these two cranial nerves like this:

Trigeminal nerve (V) – provides motor innervation to the muscles of mastication and sensory innervation to the face and head (including the teeth and gingiva).

Facial nerve (VII) – provides motor innervation to the muscles of facial expression and taste sensation to the tongue.

The Trigeminal Nerve

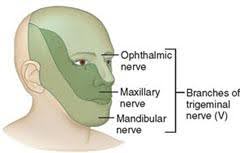

The trigeminal nerve gets its name from its three roots: ophthalmic, maxillary, and mandibular. The ophthalmic (V1) and maxillary (V2) roots are only sensory in nature, meaning that their nerve endings transmit sensation to the brain from facial structures but do not aid in movement. The third or mandibular division (V3) has a sensory root and a motor root. It is the motor root of the mandibular division that causes the muscles of mastication to contract.

The diagram to the right shows the regions of the face and the division of the trigeminal nerve that provides each with sensation. The upper face, as you can see, is innervated by the ophthalmic division. Damage to the nerve would render the affected area numb. Similarly, the midface is innervated by the maxillary division and the lower face by the mandibular division.

|

|

| Anatomical illustration of the human skull displaying the divisions of the Trigeminal nerve, with the Ophthalmic (V1), Maxillary (V2), and Mandibular (V3) nerves color-coded and mapped throughout their respective paths. | An illustration of a human face showing the areas served by the branches of the trigeminal nerve, specifically highlighting the Ophthalmic, Maxillary, and Mandibular nerves. |

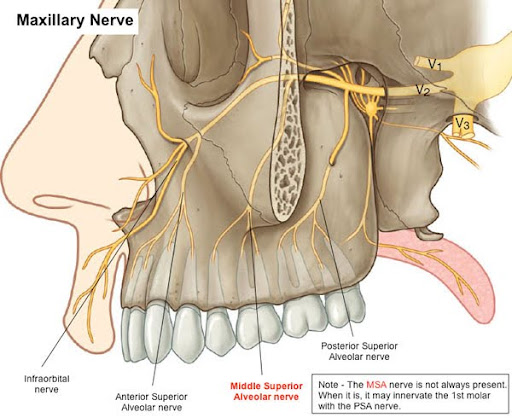

The Maxillary Nerve

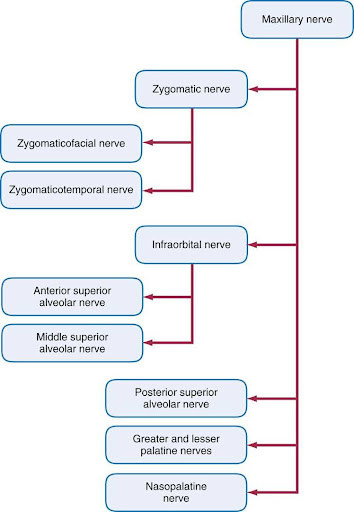

The maxillary division of the trigeminal nerve provides sensation to the maxillary teeth, the periosteum, the maxillary sinuses and the soft palate. The maxillary nerve subdivides into the:

- The anterior superior alveolar nerve supplies the maxillary anterior teeth with their periodontal membranes and gingivae. It also supplies the maxillary sinus.

- The middle superior alveolar nerve supplies the maxillary premolars, the mesiobuccal root of the maxillary first molar, and the maxillary sinus.

- The posterior superior alveolar nerve supplies the other roots of the maxillary first molar and the maxillary second and third molars. It also branches forward to supply the lateral wall of the maxillary sinus.

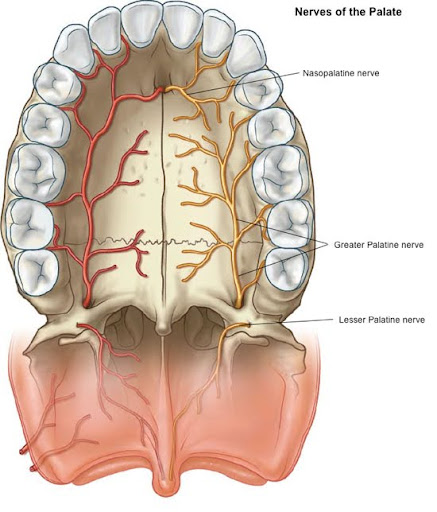

- The greater palatine nerve supplies the posterior two-thirds of the hard palate and palatal tissues around the posterior teeth.

- The nasopalatine nerve supplies the anterior third of the hard palate.

Depending on the dental procedure, the dentist may anesthetize both the tooth and the palatal tissues to make the patient comfortable.

Here is a flowchart of the maxillary nerve showing branches and sub-branches.

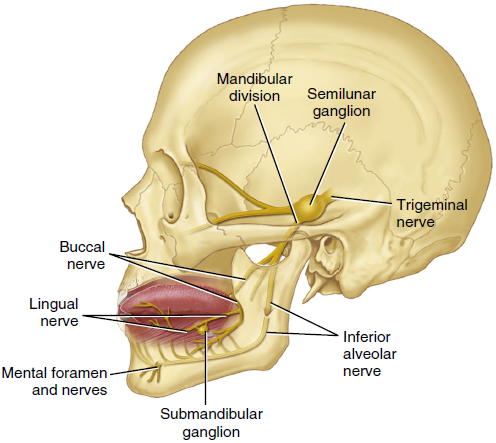

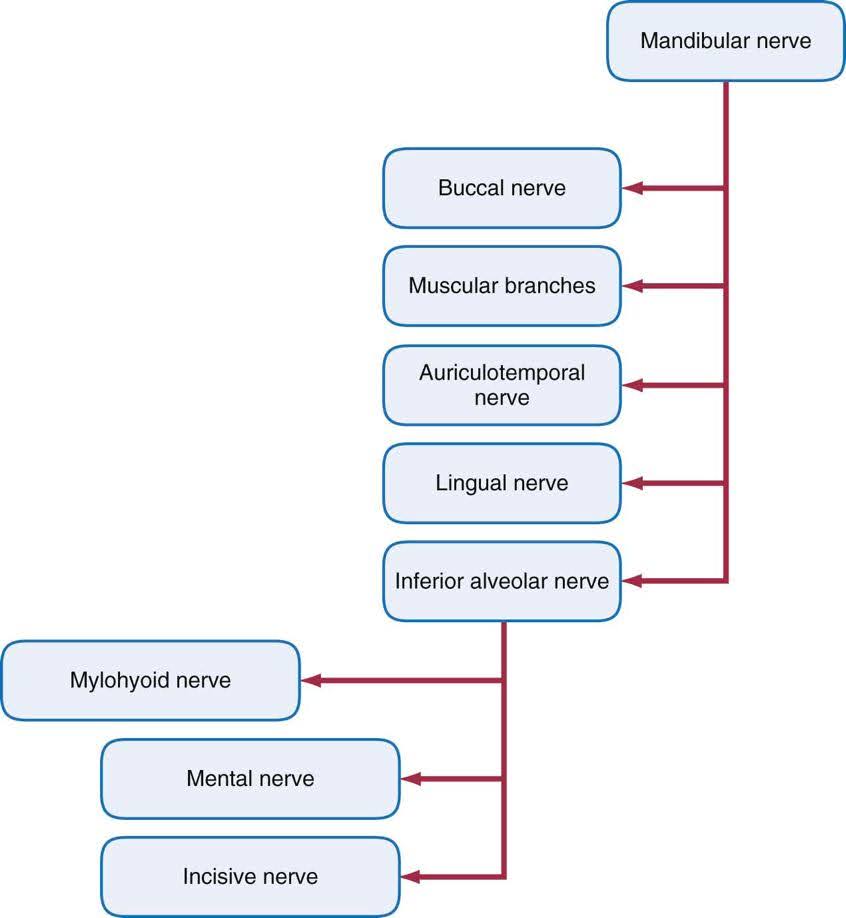

The Mandibular Nerve

The mandibular division of the trigeminal nerve has two roots: a motor root and a sensory root. The motor root has branches that stimulate the four major muscles of mastication and some additional muscles. The mandibular nerve subdivides into the:

- The buccal nerve supplies branches to the buccal mucous membrane and to the mucoperiosteum of the mandibular molars.

- The lingual nerve supplies the anterior two thirds of the tongue and branches to supply the lingual mucous membrane and mucoperiosteum.

- The inferior alveolar nerve subdivides into the following:

- Mylohyoid nerve supplies the mylohyoid muscles and the anterior belly of the digastric muscle.

- Small dental nerves supply the mandibular molars and premolars, the alveolar process and the periosteum.

- The mental nerve supplies the chin and mucous membrane of the lower lip.

- The incisive nerve supplies the mandibular incisor teeth.

Here is a flowchart of the mandibular nerve showing branches and sub-branches.

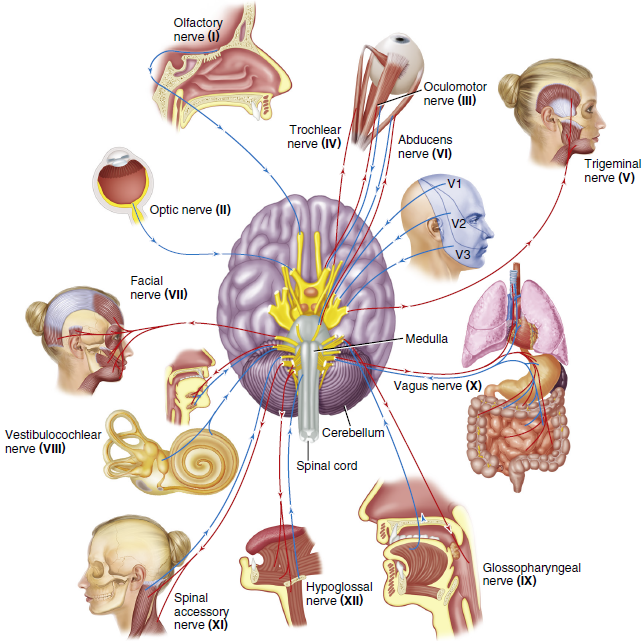

The Cranial Nerves

There are 12 pairs of cranial nerves, all connected to the brain. These nerves serve both sensory and motor functions. The cranial nerves are generally named for the area or function they serve and are also identified with Roman numerals I to XII.

The table below lists the twelve cranial nerves, their types (sensory, motor, or both), and details of each function.

| Nerve | Type | Function |

| (I) Olfactory | Sensory | Sense of smell |

| (II) Optic | Sensory | Sense of sight |

| (III) Oculomotor | Motor | Movement of eye muscles |

| (IV) Trochlear | Motor | Movement of eye muscles |

| (V) Trigeminal | Motor

Sensory |

Movement of muscles of mastication and other cranial muscles

General sensations of face, head, skin, teeth, oral cavity, and tongue |

| (VI) Abuducens | Motor | Movement of eye muscles |

| (VII) Facial | Motor

Sensory |

Facial expression, functions of glands and muscles

Sense of taste on tongue |

| (VIII) Vestibulocochlear | Sensory | Senses of sound and balance |

| (IX) Glossopharyngeal | Motor

Sensory |

Functioning of parotid gland

General sensation on skin around ear |

| (X) Vagus | Motor

Sensory |

Moves muscles in soft palate, pharynx, and larynx

General sensation on skin around ear and sense of taste |

| (XI) Accessory | Motor | Movement of muscles of the neck, soft palate, and pharnyx |

| (XII) Hypoglossal | Motor | Movement of muscles of the tongue |

Activity 2: Innervation of Muscles

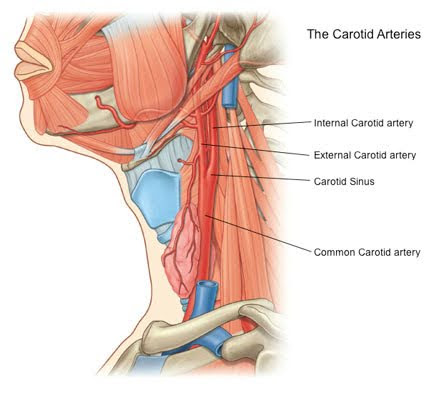

Arteries of the Head and Neck

Blood containing oxygen leaves the heart from the left ventricle and moves into the aorta. The blood is immediately directed to the head through the common carotid arteries, which are located beneath the sternocleidomastoid muscle.

The common carotid artery splits into the internal carotid and external carotid arteries in the neck. The internal carotid artery feeds oxygen to the brain, whereas the external carotid artery supplies oxygenated blood to the rest of the head and neck.

The Facial Artery

The external carotid artery has numerous branches that provide oxygenated blood to most areas of the head and neck. The facial artery is a branch of the external carotid artery and can be detected by gently palpating the mandibular notch. The facial artery passes forward and upward across the cheek toward the angle of the mouth. It then continues upward alongside the nose and ends at the inner canthus of the eye.

The facial artery has six branches that supply the pharyngeal muscles, soft palate, tonsils, posterior tongue, submandibular gland, muscles of the face, nasal septum, nose, and eyelids.

The lingual artery is also a branch of the external carotid. It consists of several branches that supply the entire tongue, the floor of the mouth, lingual gingiva, and a portion of the soft palate and tonsils.

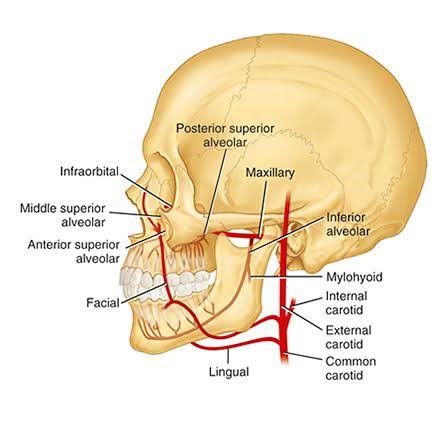

The Maxillary Artery

The maxillary artery is the larger of the two terminal branches of the external carotid artery. It arises behind the angle of the mandible and supplies the deep structures of the face. The maxillary artery divides into three sections: inferior alveolar, pterygoid, and pterygoid palatine.

The pterygoid artery supplies blood to the temporal muscle, masseter muscle, pterygoid muscles, and buccinator muscles. The pterygoid artery divides into five branches:

- The anterior and middle superior alveolar artery supplies the maxillary anterior teeth and maxillary sinuses.

- The posterior superior alveolar artery supplies the maxillary posterior teeth and gingivae.

- The infraorbital artery supplies the face.

- The greater palatine artery supplies the hard palate and lingual gingiva.

- The anterior superior alveolar artery supplies the anterior teeth.

The inferior alveolar artery branches from the maxillary artery. It enters the mandibular canal along the inferior alveolar nerve. It branches into three arteries:

- The mylohyoid artery supplies the mylohyoid muscle.

- The incisive branch supplies the anterior teeth.

- The mental branch supplies the chin and lower lip.

Tissues often receive oxygenated blood from more than one artery. This prevents damage to the tissue should one blood source be compromised. One example is the infraorbital branch of the maxillary artery, which provides blood to the same region as branches of the facial artery.

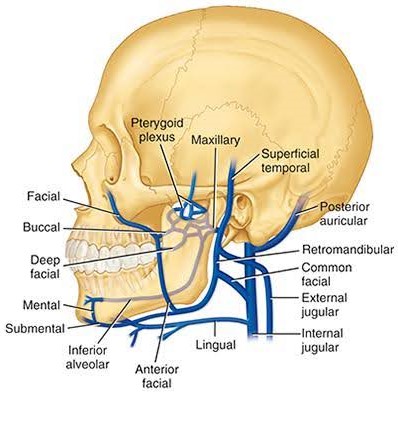

Venous Drainage of the Head and Neck

The maxillary and facial veins drain the head areas supplied by the maxillary and facial arteries. The branches are similarly named (e.g., the angular artery provides oxygenated blood to the region drained by the angular vein). The maxillary and superficial temporal veins join to form the retromandibular vein, which is located behind the ramus of the mandible, as its name suggests. The external jugular vein is the primary vessel for draining the head structures outside the cranial cavity. The internal jugular vein drains the contents of the cranial cavity (brain).

Activity 3: Circulation of the Head and Neck

Video: Blood and nerve supply of the oral cavity [16:30]

Click here for a video transcript in .docx format: Video Transcript

You have completed Module 4A. Please return to Blackboard for the next steps.

Media Attributions

- Images from: Modern Dental Assisting, 13th and 14th Edition

The structure (usually a bone) to which the muscle is attached; it doesn’t move.

The other, more movable point of attachment of a muscle; it may be bone, another muscle, or skin.

Supply or distribution of nerves to a specific body part.

(FOS-ah, FAW-seh); Hollow, grooved, or depressed area in a bone.

Arch formed when the temporal process of the zygomatic bone articulates with the zygomatic process of the temporal bone.

Strongest and most obvious muscle of mastication.

Process of the sphenoid bone, consisting of two plates.

Point of origin for internal and external pterygoid muscles.

Toward the back.

On or near the surface.

Portion of the maxillary bones that forms the support for teeth of the maxillary arch.

Toward the front.

Major cervical muscle.

Major cervical muscle.

Eight bones that cover and protect the brain.

Above another portion, or closer to the head.

Toward or from the side.

Region of the head that refers to structures closest to the inner cheek.

Structures that are closer to the feet.

Region of the head pertaining to or located near the chin.

Large blood vessels that carry blood away from the heart.

Blood vessels that carry blood to the heart.