Head and Neck Anatomy

Introduction to Head and Neck Anatomy

|

Anatomic Position and Nomenclature:

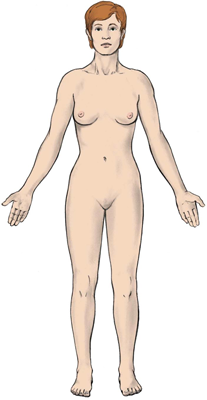

To better understand how structures are named, it is vital first to learn some of the conventions or rules used by early anatomists. These scientists positioned their specimens, often human cadavers, in a very specific way, called the anatomic position, with the body standing erect and the arms at the sides and the palms, the toes, and the eyes facing forward. Of course, it isn’t easy to get a dead body to stand erect, so no matter what position the body is actually in, this anatomic position is assumed to locate structures. |

|

Directional Terms – Superior and Inferior:

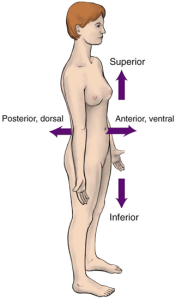

With the body in the anatomic position, we can begin assigning some locational terms to anatomic structures, starting with structures closer to the head, which are termed superior. Conversely, structures that are closer to the feet are said to be inferior. Imagine yourself sitting in someone’s navel (i.e., the belly button). All structures between your position and the top of that person’s head are located superiorly; all structures from your position down to the soles are located inferiorly. Directional Terms – Anterior and Posterior: With the body in an anatomic position, structures located toward the front of the body are termed anterior, and those toward the back of the body are called posterior. (The term ventral may be used for anterior and the term dorsal for posterior in human beings, although they rarely are in dentistry.) In the diagram shown on the left, the head is superior to the shoulders, and the nose is anterior to the ears. |

|

Directional Terms – Median and Lateral, Superficial and Deep:

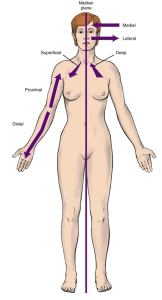

The median line (or midline) is an imaginary vertical line that divides the body into left and right mirror-image halves. When comparing two structures or reference points, the structure closer to this line is termed medial (or proximal). The structure farther from the midline is called distal (or lateral). Superficial structures lie close to the body’s surface; deep ones are closer to the body’s core. This terminology can be used to identify the location of a structure or lesion on a patient. For example: “The patient has a suspicious mole in the left infraorbital region, 1 cm lateral to the left side of the nose and 1 cm inferior to the left eye.” Documenting this information in the patient’s chart makes finding the mole on a follow-up visit easy or helps a specialist find it if the patient is referred. Regions of the Head – Frontal and Parietal: The face and head are divided into regions that are used to locate anatomical structures and, as in our example, lesions that may indicate disease. The names of these regions are based on nearby anatomic structures. You should learn to identify the regions by name to communicate with the dentist about any areas of concern you might notice. Let’s begin with the frontal region. This region, located superior to the eyes, includes the forehead extending to the top of the head. Superior and posterior to the frontal region is the parietal region, which includes the bulk of the head covered by the scalp. |

Regions of the Head

|

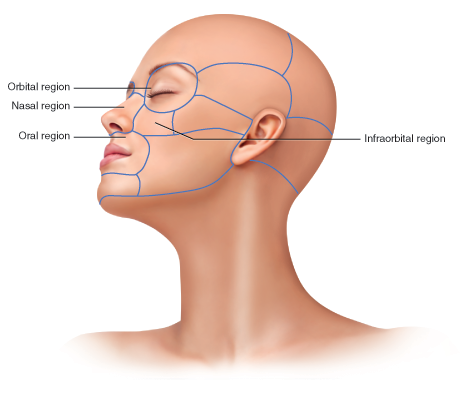

Orbital, Oral, Infraorbital, Nasal:

The anatomic term for the bony housing of the eye (the eye socket) is the orbit; as you might guess, the orbital region includes the eye and some surrounding tissues. The oral region, not surprisingly, refers to the area surrounding the oral cavity (mouth). The prefix infra means “below” (or, more appropriately, “inferior to”). The infraorbital region is the area inferior to the orbital region and superior to the oral region. It is also lateral to the next region we’ll discuss, the nasal region. As the name suggests, the nose is the most prominent feature of the nasal region. |

|

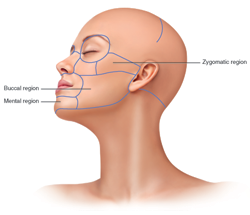

Zygomatic, Buccal, Mental:

The zygomatic region, which includes the prominence of the cheek, is located inferior to the temporal region and anterior to the auricular (ear) region. Some very important structures are here, so we’ll visit this region again soon. The buccal region is a large region that lies lateral to the oral region and includes the cheeks. Finally, the mental region sounds like it has something to do with the brain, but it doesn’t! It’s inferior to the oral region and includes the chin, known more formally as the mental protuberance. |

Activity 1: Regions of the Head

Terminology of Osseous Anatomy

Holes

Before we examine individual bones and their features, let’s learn some terminology you may come across in your study of osseous anatomy. We’ll start with holes that appear in bones.

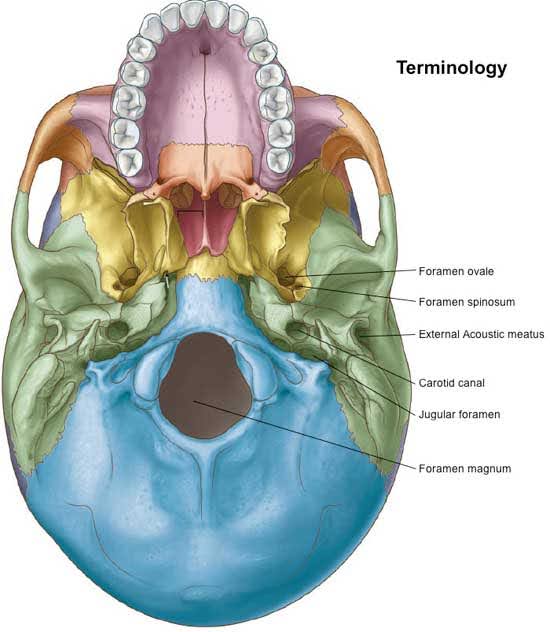

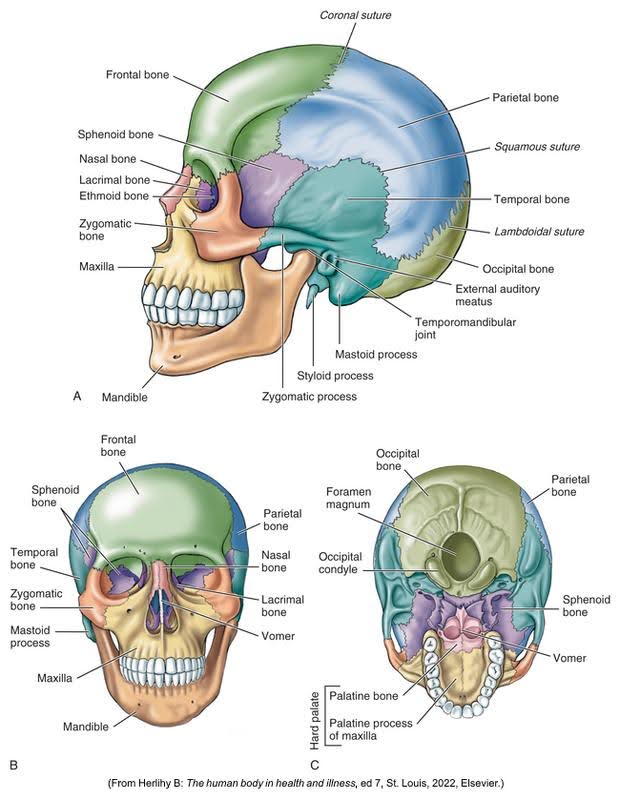

A foramen is a hole in a bone through which blood vessels and nerves pass. (The plural is foramina.) In the diagram below, you can refer to the foramen magnum located at the skull’s base. The spinal cord leaves the cranial cavity through this impressive hole. Notice the other foramina in the diagram.

A canal is a long, bony passageway. The carotid canal is pictured in the diagram.

A meatus is very similar to a canal, though the terms are not interchangeable. One cannot call the carotid canal by the name “carotid meatus,” for example.

Projections

Bony projections serve as anchors for muscles and ligaments. Here are the terms most commonly used to name bony projections:

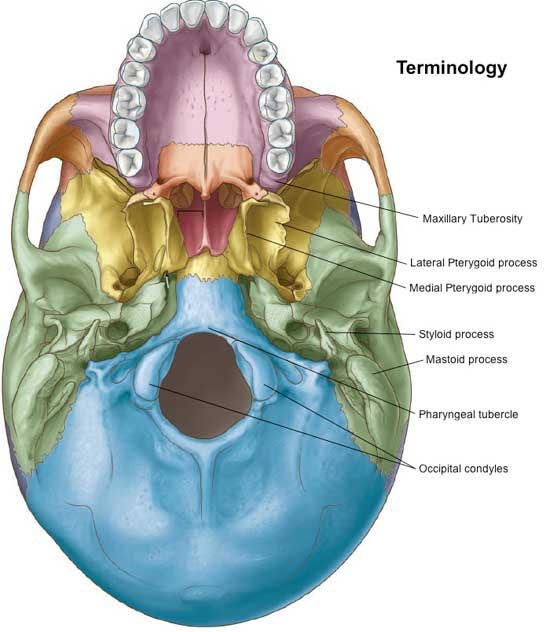

A process is a projection of bone. Some processes meet and join other bones in rigid articulations called sutures (such as the ones we covered in the discussion of the newborn’s skull); others do not. In the diagram below, you can refer to many processes, including the mastoid process and styloid process of the temporal bone, which we’ll discuss soon.

A tubercle is a small, rough bony projection; a tuberosity is a large, rounded bony projection. The maxillary tuberosity is a large, rounded, bony projection distal to the maxillary third molars. On the inside of the lower jaw (the mandible), at the midline, are the genial tubercles, which serve as points of muscle attachment.

Miscellaneous

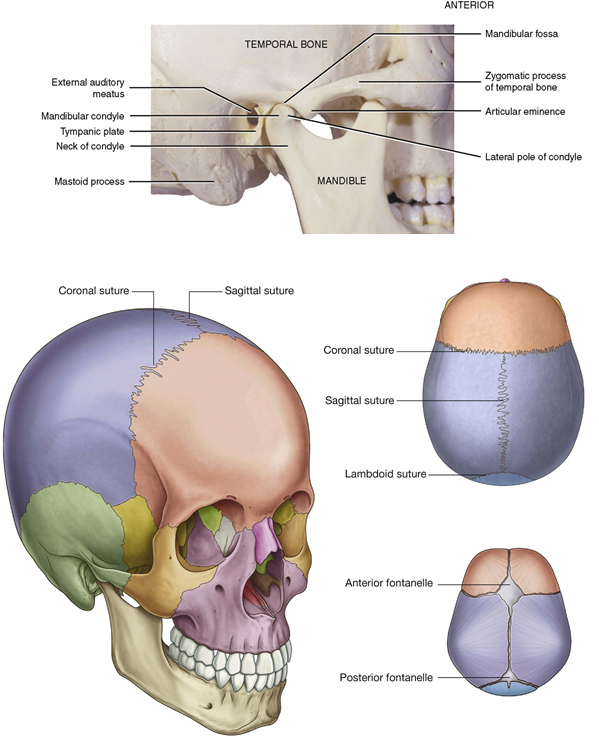

A depression in bone is known as a fossa. The fossae (plural) are there for a reason, usually to accommodate a structure that resides there. In the diagram below, you can see that the mandibular condyle sits in the mandibular fossa. This movable joint called the temporomandibular joint (TMJ) and is responsible for jaw movement that allows us to eat and speak.

Speaking of joints between bones, there are two additional joints to discuss: the suture (which we’ve already discussed in this lesson), a rigid, immovable joint between bones, and the symphysis, a cartilage joint between bones that permits limited movement. (The lower diagram shows the cranial sutures.)

Eight Bones of the Cranium

| Bone | Location |

| Frontal | The frontal bone forms the forehead above the orbits. It extends to the top of the head, partially covered by the scalp. It forms the roof of the orbits and contains hollow openings called the frontal sinuses that can become inflamed, causing a sinus headache. |

| Parietal | The two parietal bones, which form the roof of the cranial cavity, join in the midline at the sagittal suture. The frontal bone joins the two parietal bones in an articulation known as the coronal suture. |

| Occipital | The occipital bone forms the posterior and inferior portion of the cranium. Its most prominent feature is the foramen magnum, the large opening on the base of the skull through which the spinal cord exits the cranial cavity. The lambdoidal suture joins the occipital bone with the two parietal bones. |

| Temporal | The two temporal bones form a portion of the side and base of the cranium. |

| Sphenoid | The sphenoid bone looks like a bat when removed from the skull. It has a central body with greater and lesser wings extending outward and pterygoid processes extending downward like legs. The sphenoid sinus, located in the body of the bone, drains into the nose. |

| Ethmoid | The ethmoid bone, which also contains a sinus, is centrally located in the skull. The middle and superior nasal conchae extend from the ethmoid bone into the nasal cavity. The perpendicular plate of the ethmoid bone also forms a portion of the nasal septum, which divides the nasal cavity into right and left nares (nostrils). |

The diagram below displays all the bones of the skull. The top of the diagram(A) is a side view and the smaller diagrams at the bottom are (B) the frontal view and (C) the base of the skull.

Facial Bones

Click on the hotspots in the image below to see the 14 facial bones content.

Activity 2: Bones of the Cranium

Activity 3: Bones of the Face

The Temporomandibular Joint (TMJ)

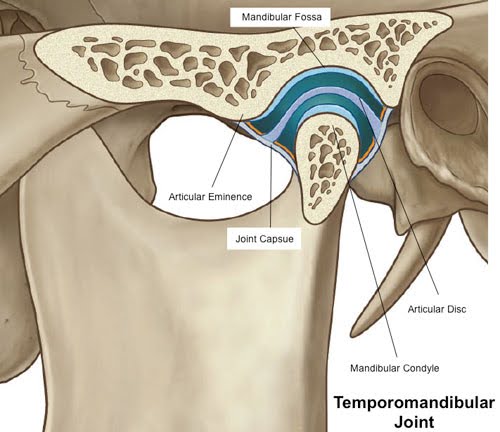

The temporomandibular joint (TMJ) articulates the movable mandible and the skull’s temporal bone. It comprises numerous parts that work together to permit such activities as eating and talking. They include:

- The mandibular condyle, a bulbous bony projection of the condyloid process of the mandible

- The mandibular (or glenoid) fossa of the temporal bone, a depression where the condyle sits

- The articular eminence, a bony slope anterior to the mandibular fossa down which the condyle rides when the jaws are opened

- The articular disc or meniscus is a piece of cartilage that sits between the condyle and the fossa/eminence

- The joint capsule, which surrounds the condyle and is attached around its neck and to the temporal bone above

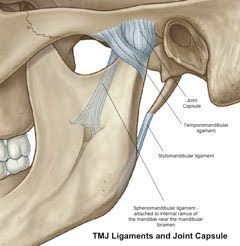

- Three ligaments associated with the TMJ, whose role is to limit the extent of mandibular movement

Below are diagrams of the temporomandibular joint and the TMJ ligaments and joint capsule.

|

|

TMJ Movement

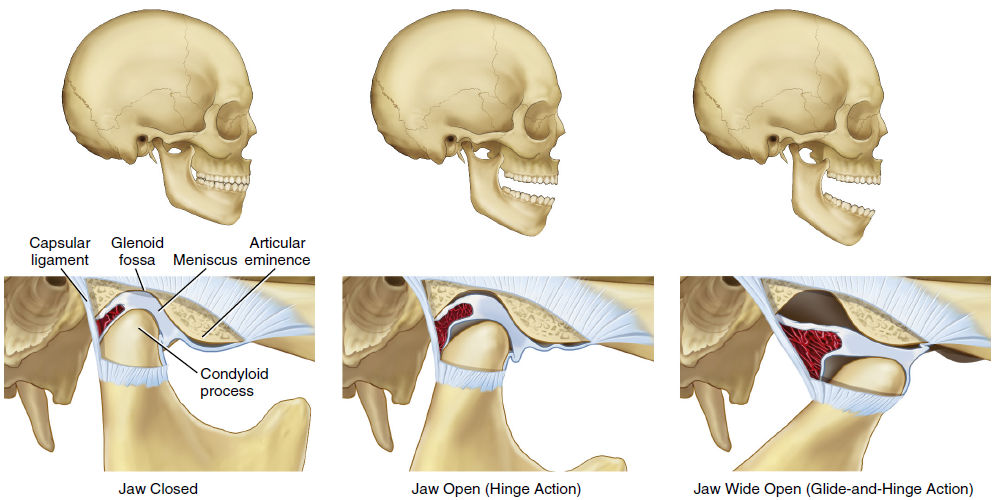

The TMJ performs two types of movement: hinge and gliding.

When you open your mouth (mandibular depression), the initial joint movement is similar to that of a door hinge, with the condyle rotating within the fossa. In fact, the actual hinge movement is between the condyle and the underside of the articular disc. As you open your mouth wider, the articular disc glides forward (mandibular protrusion) down the articular eminence. It is the action of the lateral pterygoid muscles, with an assist from the hyoid muscles (and gravity), that causes mandibular depression.

Closing the jaws (mandibular elevation) requires the combined action of the masseters, temporalis muscles, and medial pterygoids to return the condyle back into the fossa. This elevation is a reverse of the depression movement described with a gliding action between the disc and the eminence, returning the condyle to the fossa and a hinge movement between the condyle and the disc, restoring the jaws to their resting position.

The diagram below displays the hinge and gliding actions of the TMJ.

Temporomandibular Disorders

A patient may experience a disease process associated with one or both of the TMJs, called a temporomandibular disorder (TMD). TMD is a complex disorder involving such factors as:

- Stress

- Clenching, holding teeth tightly together for prolonged periods

- Bruxism habitual grinding of the teeth, especially at night

TMD can also be caused by trauma to the jaw, systemic diseases such as osteoarthritis, or wear due to aging. Malocclusion may also put a strain on the joint.

TMD diagnosis and treatment can be difficult and frequently require a multidisciplinary approach. A complete analysis of a patient’s condition may require involving other health professionals such as physicians, psychiatrists, neurologists, and others.

One reason TMD is difficult to diagnose is that symptoms may vary. The most common symptoms are pain, joint sounds, and limitations in movement.

Patients with TMD may report a variety of pain types such as:

- Headache

- Pain in and around the ear (when no infection is present)

- Pain when chewing

- Pain in the face, head and/or neck

- Spasms of the muscles

Joint sounds may be clicking, popping, or crepitus when opening the mouth. Crepitus is the cracking sound that can be heard in the joint.

Limitations in movement may lead to difficulty and pain when chewing, yawning, or opening the mouth widely. The most common cause of restricted movement is trismus, which is spasms of the muscles caused by mastication. Trismus can severely limit a patient’s ability to open their mouth. The patient may describe this as the jaw got “locked,” “gets stuck,” or “goes out.”

Checking for Temporomandibular Disorder

The image below shows the patient palpating during the movements of both temporomandibular joints. The dental professional is having the patient open and close her mouth to check for pain, sounds, and other symptoms that may be related to TMD.

You have completed Module 4. Please return to Blackboard for the next steps.

Media Attributions

- Images from: Modern Dental Assisting, 13th and 14th Edition

The body standing erect face forward, feet together, arms hanging at the sides, and palms forward.

Above another portion, or closer to the head.

Structures that are closer to the feet.

Toward the front.

Toward the back.

Imaginary vertical line that divides the body into left and right mirror-image halves.

Toward or nearer to the midline of the body.

Farther away from the trunk of the body; opposite of proximal.

Toward or from the side.

On or near the surface.

Closer to the bodies core.

Region of the head below the orbital region.

Area superior to the eyes, includes the forehead extending to the top of the head.

Pertaining to the walls of a body cavity.

Region of the head pertaining to or located around the eye.

Region of the head pertaining to or located near the mouth.

Region of the head that pertains to or is located near the nose.

Region of the head pertaining to or located near the zygomatic bone (cheekbone).

Region of the head superior to the zygomatic arch.

Region of the head that refers to structures closest to the inner cheek.

Region of the head pertaining to or located near the chin.

Part of the mandible that forms the chin.

Small round opening in a bone through which blood vessels, nerves, and ligaments pass; plural, foramina.

Large opening in the occipital bone that connects the vertical canal and the cranial cavity.

External opening of a canal.

Prominence or projection on a bone.

Process that extends from the undersurface of the temporal bone.

Large, rounded area on the outer surface of the maxillary bones in the area of the posterior teeth.

Suture that is located at the midline of the skull, where the two parietal bones are joined.

Line of articulation between the frontal bone and parietal bones.

Region of the head overlying the occipital bone and covered by the scalp.

Process of the sphenoid bone, consisting of two plates.

Projecting structures found in each lateral wall of the nasal cavity and extending inward from the maxilla; singular, concha.