5.5 Vertical Integration

Vertical integration is a strategic decision that plays a critical role in shaping corporate strategy. It refers to a firm’s efforts to gain control over multiple stages of its industry’s value chain—either upstream (toward suppliers) or downstream (toward customers). The primary objectives of vertical integration include:

- Enhancing market power

- Reducing transaction and coordination costs

- Securing reliable access to inputs or distribution channels

- Improving product quality and delivery performance

All firms rely on external sources for at least some of their inputs—whether raw materials, components, or services. The degree of vertical integration reflects how many of these activities a firm chooses to perform internally rather than outsourcing. This decision is often framed as a “make or buy” choice:

- Make: Perform the activity in-house (greater integration)

- Buy: Outsource the activity to external suppliers (less integration)

Once these decisions are made, firms must develop systems to coordinate and integrate internal processes with those of external partners to ensure seamless operations.

Types of Vertical Integration

Vertical integration can take three primary forms:

Backward Integration (Upstream Integration)

This involves acquiring or controlling sources of supply. For example, an automobile manufacturer might own a tire company or a steel plant. The goal is to ensure a stable supply of inputs, reduce dependency on suppliers, and maintain consistent quality. Historically, companies like Ford Motor Company used this strategy extensively to control their entire supply chain.

Forward Integration (Downstream Integration)

This strategy involves gaining control over distribution channels or retail outlets. For instance, a manufacturer might acquire a chain of retail stores to sell its products directly to consumers. This allows the firm to capture more value, improve customer experience, and respond more quickly to market changes.

Balanced Integration

Balanced integration combines both backward and forward integration. Firms adopting this approach aim to control both input sourcing and product distribution, thereby maximizing control over the entire value chain.

Image Description

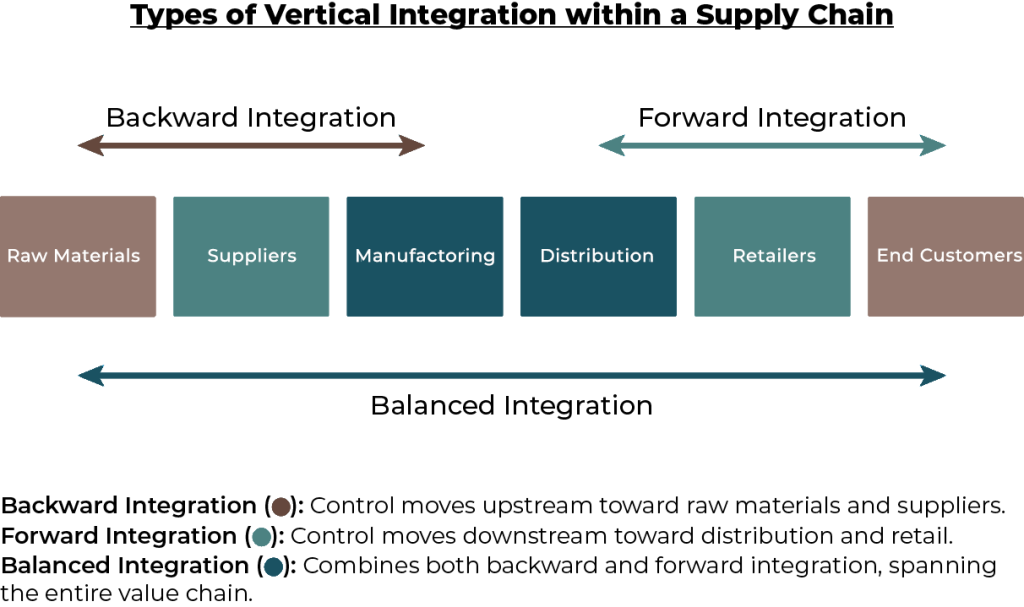

A diagram titled “Types of Vertical Integration within a Supply Chain” showing a horizontal flow from “Raw Materials” to “End Customers” through the stages: Raw Materials, Suppliers, Manufacturing, Distribution, Retailers, and End Customers.

- Backward Integration is illustrated with a double-headed arrow pointing leftward from Manufacturing toward Raw Materials, indicating control moving upstream.

- Forward Integration is shown with a double-headed arrow pointing rightward from Manufacturing toward End Customers, indicating control moving downstream.

- Balanced Integration is represented by a long arrow spanning both directions across the entire chain from Raw Materials to End Customers.

Below the diagram, definitions are provided:

- Backward Integration: Control moves upstream toward raw materials and suppliers.

- Forward Integration: Control moves downstream toward distribution and retail.

- Balanced Integration: Combines both backward and forward integration, spanning the entire value chain.

Advantages and Disadvantages of Vertical Integration

| Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|

| Increases market share and competitive advantage | Higher operational complexity and management burden |

| Facilitates entry into foreign or new markets | Risk of inefficiency if the firm lacks expertise in new activities |

| Enhances product quality and consistency | Reduced flexibility due to fixed internal supply or distribution structures |

| Improves delivery reliability and responsiveness | Potential for lower innovation due to reduced external competition |

| Reduces transaction costs and dependency on external suppliers or distributors | Capital-intensive and may require significant upfront investment |

“4. Process Management: Types of Process and its Implication in Operation Strategy” from Operations Management by Sudhanshu Joshi is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted.—Modifications: Used section 4.8; reworded; added further content.