20 Reflecting on and Transforming the Environment

“The learning environment is often viewed as “the third teacher”: it can either enhance learning, optimizing [children’s] potential to respond creatively and meaningfully, or detract from it” (Ministry of Education, 2012). With this in mind, it’s so important that educators observe and reflect on the environment of the early learning program that children spend time in.

The quote above refers to an environment that enhances learning and encourages children to be creative and engage in meaningful ways, so what does that look like? One of the most important qualities of such a space is that it supports all children in all developmental areas.

Universal Design for Learning

This notion of ensuring that all children can access and enjoy a barrier-free learning environment is called Universal Design for Learning (UDL).

Multiple Means of Representation

With this approach, an early learning environment includes multiple means of representation, and this means that children are presented with and can access information in multiple ways. For example, when an educator in a kindergarten classroom needs to tell the children about an upcoming transition to outdoor recess, rather than just tell children verbally, they might also point to a visual schedule hanging on the wall that has a picture of the play structure in the yard that the children know represents outdoor playtime. The fact that the information is presented to children both verbally and visually benefits all children and helps ensure that the message is received by everyone.

Multiple Means of Action and Expression

An early learning environment must also allow for multiple means of action and expression, and this means that children can express what they know and understand in a way that works best for them. For instance, when an educator is reading a story and shows the children a picture of a family of dogs and asks them how many dogs there are, some children might yell out, “Three!” Some children might hold up three fingers. Other children might come up to the book and touch one dog at a time. These are all ways that children can communicate their understanding of numeracy. If we required children to only say the number, we might underestimate the understanding of the other children who can much more easily communicate that knowledge in kinesthetic ways.

Note. Image generated using the prompt “young child holding up three fingers,” by Adobe, Adobe Firefly, 2024 (https://firefly.adobe.com/).

Multiple Means of Engagement

Finally, the environment needs to provide multiple means of engagement, and this refers to providing children with choices in how they want to play and learn. Some children might enjoy learning about math by figuring out how many dolls they have sitting at the table in the dramatic play area and ensuring they have the same number of plates, whereas others might prefer counting how many blocks are in their tower and determining that theirs has more than their friend’s. We all learn in different ways, and educators must always support children’s interests and encourage play-based learning.

In the remainder of this section, we will consider how we can apply the cycle of observation and UDL principles to the social-emotional, physical, and temporal environment.

The Social-Emotional Environment

When we hear the word “environment,” we often think of the physical space, but a significant part of an early learning environment include the interactions that take place in those settings.

“Research has suggested that educator-child relationships play a significant role in influencing young children’s social and emotional development. In studies of educator-child relationships, children who had a secure relationship with their preschool and kindergarten educators demonstrated good peer interactions and positive relationships with educators and peers in elementary school. On the other hand, children who had insecure relationships with educators had more difficulty interacting with peers and engaged in more conflict with their educators. In addition, research has shown that educators’ interaction styles with children help children build positive and emotionally secure relationships with adults. For instance, educators’ smiling behaviors, affectionate words, and appropriate physical contact help promote children’s positive responses toward educators. Also, children whose educators showed warmth and respect toward them (e.g., educators who listened when children talked to them, made eye contact, treated children fairly) developed positive and competent peer relationships. Moreover, children who had secure relationships with their educators demonstrated lower levels of challenging behaviors and higher levels of competence in school” (CSEFEL, n.d., p. 3).

Responding to Children’s Needs

It is evident that the social-emotional environment is key to a child’s well-being and healthy development. A significant part of creating an environment with a healthy social-emotional climate is to observe children’s needs and respond accordingly. For instance, if a child is dropped off by their parent in the morning and begins to cry, a responsive educator would observe that and approach the child, get down to their level, remind them that Mommy will be back, and offer physical comfort. Educators need to read children’s cues to determine what they need, so if that child turns to the educator and snuggles in for a hug, it is clear that that is what the child wants and needs in that moment.

Image by freepik

However, if the child continues to look out the window with both of their hands pressed against it, the educator should observe that the child is not showing signs of wanting to cuddle. The educator might provide a reassuring rub on the child’s back, and they would again observe to see how the child responds to assess what the child needs. Perhaps it’s enough for the educator to just be near the child, and the educator would be able to determine that just by observing the child. With these different educator responses, we are allowing children to engage with educators in a way that works best for them. Some children might appreciate and respond to an educator’s suggestion to draw a picture for their mom that they can give to her when she comes back, while other children might just need some time to sit quietly with the educator before they feel ready to engage with their friends in play.

So, the key in providing a healthy social-emotional environment is to observe children to understand what they want and need and then respond accordingly. This will look different for each child, but what is true for all children is that they need an educator who is warm, kind, and lets each child know that they are valued.

The Physical Environment

When you look around an early learning program and see an art centre with easels and lots of loose parts to create with, a quiet corner to look through picture books with beautiful illustrations, and a dramatic play area set up like a veterinary clinic, this is all part of the physical environment. These varied options provide multiple means of representation, and children have different ways they can choose to engage and express themselves.

When educators observe children in the physical environment, they might notice that a child seems drawn to the reading corner, but after very quickly flipping through a book, they leave the space. That educator might wonder if that child would perhaps enjoy a different way of engaging with that book and decide to include an audio station with headphones so they can listen to the book as they turn each page. Providing these multiple means of representation and engagement would benefit all children.

Variety of Materials

It is important that educators create spaces that have a variety of materials to reflect children’s different interests. There should be lots of open-ended items for children to explore in any way they like; these types of items like loose parts and art materials where there is no right or wrong way to do things (as opposed to puzzles, for example, where there is only one way for it to be completed) support different skill levels and focus on the process rather than the product. These materials promote children’s enjoyment and feelings of success because there is no way for them to fail when there are no clear expectations that must be met.

Aesthetics and Design

The aesthetics and design of an early learning environment are also important to consider because they have an impact on how children feel about and interact with the space. Imagine a room with bold orange and red walls, fluorescent lighting, and lots of bright commercial items on the bulletin boards like alphabet letters and posters. The room has tons of materials in unlabeled bins scattered throughout the room placed on shelving that runs around the perimeter of the room, leaving a large open space in the center. In environments like these, you would likely observe children running around or playing aimlessly. Children who are feeling overwhelmed by the frenetic energy and noise level in the room have no way to escape due to the design of the room and lack of a quiet and protected corner. An educator in that room might observe the chaos and overstimulation and recognize that the aesthetics and design of the room must be changed.

They may decide to transform the room by switching to calm colour tones, relying on natural lighting from the windows and soft lamps, and displaying the children’s artwork carefully and selectively. They choose to move the shelves and use them as low dividers to section off the space into different areas, which would allow them to create a quiet corner that is placed on the opposite site of the room from the bustling blocks area. Some of the materials could be put in storage to reduce clutter, and everything else could be stored in clear bins with pictures that show where everything can be found and where everything should be put back. After making the change, the educator would likely notice that the room is much quieter now that the children aren’t running around in circles and are dispersed throughout the different areas of the room. Children who need a break would finally have a quiet place to go.

In this latter physical environment, educators reflected their observations and responded by making changes that benefitted all children.

Accessibility

When we consider the physical environment, we also need to take into account accessibility to ensure we are providing a space that all children can enjoy, regardless of any barriers they may face. The space needs to have wide enough areas to accommodate any children who rely on wheelchairs or assistive walking devices for mobility. Furniture needs to be child-sized so all children can manage on their own. As much as possible, information should be presented visually (for example, a visual schedule or labels on bins) so children who cannot read or who process visual information more effectively are not hindered. Observation plays a significant role here. For example, if an educator notices a child who uses a wheelchair is struggling to reach the soap dispenser that is mounted behind the sink, a solution must be found for the soap to be placed where the child can reach it.

Outdoor Environments

We must also consider the outdoor environment because it is such an important component of an early learning program. All of the elements that were discussed above apply to the outdoor spaces that children spend time in on a daily basis. Children need lots of options when it comes to materials they can engage with. Some children enjoy being extremely active when outside and will choose to run with their friends or seek out gross motor toys like balls, scooters, and hula hoops. Other children may prefer quiet activities like drawing with chalk, playing in the sand, and inspecting the leaves on the bushes.

Image by Freepik

Just like with indoor spaces, educators need to observe children as they play outside to get an understanding of what their interests and development are, what materials might be beneficial, and what changes should be made. For instance, if an educator notices a group of children are constantly arguing over the one scooter, they might decide to purchase more scooters. If an educator observes several children who are constantly gravitating to the chalk to draw on the concrete, they might introduce additional materials like cups of water and paint brushes to “paint” on the concrete.

Just like in indoor spaces, educators must provide children with multiple means of expression, engagement, and representation in outdoor spaces. They must also observe how children engage with the environment and materials and make changes accordingly to ensure children’s interests are reflected and their holistic development is promoted.

Temporal Environment

The temporal environment of an early learning program refers to the schedule, routine, and flow of the day. One of the most important things educators can do to support children is to provide a predictable and regular schedule where children can easily anticipate what’s coming next. This helps to reduce children’s anxieties because they know that, for example, every day after recess is lunchtime and then naptime. Visual schedules that have been mentioned a couple of times above are an important part of the temporal environment and supporting all children.

Another important element of the temporal environment is to schedule large periods of time where children can become deeply engaged in their play without being interrupted. Educators should also provide children with a balance of active and quiet activities, and group and individual activities. When switching from one routine to another, children should be notified of the transition both verbally and non-verbally (i.e. turning lights off and on, ringing a bell, clapping hands, etc.) Again, these multiple means of engagement and representation benefit all children.

Image by Ozant Liuky from Pixabay

Observation plays a role in the temporal environment when educators take note of how children respond to the schedule and routine. For instance, if educators notice that having circle time right at the start of the day is difficult because the children are very excited to play with the materials in the room and talk with their friends, they might decide to have circle time an hour into the day to give children time to settle in first. And as per the cycle of observation, educators would then continue to observe to see how children respond to that change.

The Environment Rating Scales (ERS)

The Environment Rating Scale is a standardized assessment tool that can help educators evaluate and improve the quality of their program. This tool looks at the social-emotional, physical, and temporal environment.

- Interactions between educators and children

- Interactions among adults (educators, other staff, and parents)

- Interactions among the children

- Interactions children have with the many materials and activities in the environment

- The features, such as space, schedule and materials that support these interactions

These elements are assessed primarily through observation and have been found to be more predictive of child outcomes than structural indicators such as staff to child ratio, group size, cost of care, and even type of care, for example child care center or family child care home.

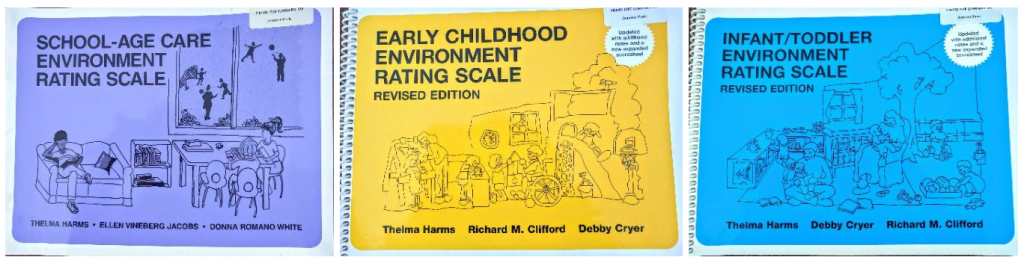

There are 4 Environment Rating Scales:

- The Infant and Toddler Environmental Rating Scale (ITERS) for programs serving young learners aged 6 weeks to 30 months

- The Early Childhood Environmental Rating Scale (ECERS) for preschool programs serving children aged 3-5 years

- The School-Age Child Environmental Rating Scale (SACERS) for afterschool programs serving children aged 5-12 years

- The Family Child Care Environmental Rating Scale (FCCERS) for family childcare programs serving children aged 6 weeks to 12 years.

Rating Scale Texts Image Credit: Image by College of the Canyons ZTC Team is licensed under CC BY 4.0

Why Use Environment Rating Scales

The scales are used in a variety of ways including for self-assessment by center staff, preparation for accreditation, and voluntary improvement efforts by licensing or other agencies. For example, some early learning programs bring in trained personnel who do assessments and provide guidance and technical assistance so that childcare centers and homes can increase their quality of care. Some areas use scale scores as part of a 5-star rated license system. As part of that system, centres and home daycare programs are awarded either one or two stars based on compliance with licensing standards. Programs may voluntarily apply for an additional three stars based on a set of quality measures including the licensing compliance record, teacher and director education, and the levels of process quality as measured by the appropriate environmental scale. Only the lowest level of licensing is mandatory. However, an additional fee is paid to the provider of subsidized care for each additional star earned voluntarily.

The ERS Tool

As suggested by ERS, in order to provide high-quality care and education experiences to all children and their families, an early learning program must provide for the three basic needs all children have:

- Protection of their health and safety

- Building positive relationships

- Opportunities for stimulation and learning from experience

Let’s take a closer look at how to use the Early Childhood Environmental Rating Scale (ECERS-3) for preschool programs serving children aged 3-5 years. The Scale consists of 35 items organized into 6 subscales:

- Space and Furnishings

- Personal Care Routines

- Language and Literacy

- Learning Activities

- Interaction

- Program Structure

Within each subscale there are indicators that are arranged in a hierarchical order with basic needs at low levels and the more educational and interactional aspects at higher levels.

Scoring:

- 1 = inadequate

- 3 = minimal

- 5 = good

- 7 = excellent

After you’ve completed the rating scale (focused either on children’s development or the early learning environment), you need to interpret that information. What was revealed? How should you respond? Are there changes to make to the environment or experiences that can be planned for the children?

Because rating scales are so similar to checklists, the advantages and disadvantages are essentially the same, except there is an added advantage of the flexibility in scoring. However, this then brings the increased likelihood of losing inter-rater reliability resulting in different observers disagreeing on the rating assigned due to subjectivity.

Pin It! Reliability and Validity Defined

Reliability means that the scores on the tool will be stable regardless of when the tool is administered, where it is administered, and who is administering it. Reliability answers the question: Is the tool producing consistent information across different circumstances? Reliability provides assurance that comparable information will be obtained from the tool across different situations.

Validity means that the scores on the tool accurately capture what the tool is meant to capture in terms of content. Validity answers the question: Is the tool assessing what it is supposed to assess?

Resources

Center on the Social and Emotional Foundations for Early Learning. (n.d.). Building positive teacher-child relationships. https://static.virtuallabschool.org/activities/self/PS.Self_1.Introduction_A1.BuildingPositiveRelationships.pdf

ERSI. (n.d.). Related work. https://www.ersi.info/scales_relatedwork.html

Fenning, K. & Wylie, S. (2020). Observing young children: Transformative inquiry, pedagogical documentation and reflection (6th ed.). Nelson.

Ministry of Education. (2012). 1.3 The learning environment. https://www.ontario.ca/document/kindergarten-program-2016/learning-environment

Mistrett, S. G. (2017). Universal design for learning: A checklist for early childhood environments. Center on Technology and Disability. https://va-leads-ecse.org/Document/zxbIhX_YCJNMoZ8Ys3rgdvERGbr0g1ZW/ADA-UDL-Checklist-EC.pdf