3 Ethical Guidelines when Observing Children

In most early learning programs, a typical day includes educators taking pictures of the children engaged with others and materials, so that they will have ample documentation. Pedagogical documentation especially when observing young children, involves a range of ethical considerations and decision-making processes across philosophical, practical, and policy dimensions.

Philosophical Considerations

- Respect for child: Observations should be conducted with the utmost respect for the child’s privacy and individuality. This involves considering how documentation practices align with the principles of treating children with dignity and recognizing their agency in the learning process.

- Purpose: Reflect on the intent behind observing and documenting children. The goal should be to support their development and learning, not merely to collect data. This philosophical stance emphasizes that documentation should enhance educational experiences rather than serve as a tool for evaluation or control.

Practical Considerations

- Consent and Confidentiality: this needs to be on file for each child in your program so you are aware of the parameters that parents have agreed to. This information and what is observed is kept at the centre- further details about confidentiality are discussed later in this chapter.

- Accuracy: be mindful of the accuracy of observations and avoid biases. Documenting what is actually observed (heard and seen), rather than interpreting.

- Invisible: strive to make observations as unobtrusive as possible to minimize any potential impact on the child’s natural interactions.

Policy Considerations

- College of Early Childhood Educators: adhere to the Code of Ethics and Standards of Practice .

- Child Care and Early Years Act: Ontario government regulations for licensed centres.

- Program Handbook: these are the policies and procedures that are specific to each early learning environment.

Ponder This

Does the educator’s presence change the context of the child’s experience?

Does the thought of being monitored make the child behave any differently?

How does the child feel about having their picture taken?

Are educators overly concerned about capturing children in precious moments rather than being engaged in teachable moments?

As an ECE student who is learning to observe and document a child’s development, it is important for you to be aware of some ethical considerations when observing children, and that’s what we will focus on in this chapter.

Pin It

Ethics– defined- derived from the Greek word ‘ethos’ which means character or conduct. It is the concept of right and wrong, good and bad. Ethics are rules, principles and values that as a society or governing body we have chosen to follow. It is a system of moral principles. Examples of ethics includes: honesty, integrity, respect and loyalty.

Confidentiality

One of the standards of practice outlined by the College of Early Childhood Educators (2017) is related to confidentiality, and this is a key consideration when observing children.

One part of confidentiality involves protecting children’s identities in our documentation. For example, imagine you’re observing a child named Jensen, so you’re jotting down what you see and hear. Now imagine that Sam comes over and knocks down Jasper’s tower. It would be important to not include Sam’s name on this documentation (especially if it’s going to be shared with Jensen’s family) because that wouldn’t be respecting Sam’s privacy. (Also, if the observation is focused on Jensen, it doesn’t matter who knocked down the tower as we’re only interested in Jensen’s reaction to what happened; Sam knocking down the tower is definitely worthy of making note of, but that would need to be separate from Jensen’s observation). One way around this is to use initials for other children in written observations.

Another part of confidentiality involves protecting the information that contains children’s personal information, so we need to be sure that all of our notes are put somewhere safe. This might mean storing them in a cupboard or locked drawer that only other educators in the child’s program can access. We should share our observations only with the children’s families or any other relevant professionals, for example, the child’s doctor, speech-language pathologist, or social worker. Not only can we not share our written observations with anyone who is not directly involved in the child’s care, but what we observe must not be shared verbally with anyone who doesn’t need to know the child’s information. For example, if we are in the staff room with other educators and we share a child’s story about his parents who were fighting that morning, this is a breach of that family’s confidentiality. Breaching confidentiality can erode trust between families and educators and potentially harm the child’s well-being. It also creates a culture in the program that supports this lack of professionalism and disregard for our responsibility to support children and their families.

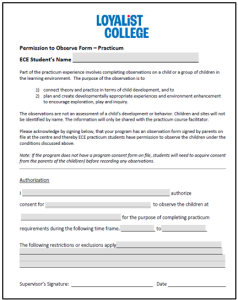

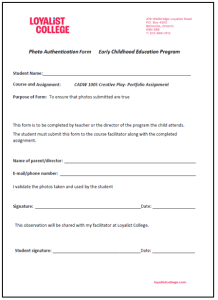

Sample confidentiality agreement from Loyalist College

Consent to Observe

Before conducting observations, educators need to ask for permission. A program may have consent as part of their intake/registration. If not then it needs to be from the child’s family, providing them with clear information about the purpose, methods, and potential uses of the observations. It is important to let the family know how the data will be collected, stored, and shared. Also, when children are old enough, they should be informed that they’re being observed and why. Children are often very interested in the process and like being the focus of attention! But if, for whatever reason, they express that they do not want to be observed, we must respect that. Obtaining informed consent respects the autonomy of families and children.

Informed consent also applies to taking pictures (and videos) of children. Some families do not want their child’s picture taken, and some might be okay with it being taken but have specific instructions about where they can and cannot be posted, so we must be aware of who you can take pictures of and what you’re allowed to do with those pictures. Parents may decline to have their child’s photo taken for any reason, and some reasons may include safety or culture. While parents do not need to give reasons for declining, if they’re comfortable providing you with a reason, it can be helpful. For instance, if they’re worried about a non-custodial parent seeing the child’s picture on the website and learning about the child’s whereabouts, this is important information for you to know so you can also ensure the child’s safety during pickup and while outside playing (as you’ll know who to look out for). The children we’re observing might not be old enough to provide consent to have their picture taken, but if a child ever says or nonverbally indicates that they don’t want their picture taken, we must respect that.

Sample consent forms for students from Loyalist College

Valuing and Respecting Children

Family living on street

Imagine these are pictures of you. You’re with your children and living through a very difficult time in your life when someone comes up to you and takes a picture. They then sit down and, while watching you with your children, write down some notes. How do you think you would feel? It’s fair to assume that you would probably feel self-conscious and like this person is infringing on your privacy. You would probably feel as though the observer should have asked before taking your picture and writing down their thoughts about you. Now imagine they write down that you’re ignoring your children, that you look like you’re in a bad mood, and that your clothes are tattered and dirty. If you were to read what they wrote, you would probably feel that they didn’t take the whole context into account and that what they documented made it sound like you were an awful and neglectful mother, when in fact you just fled your home that was unsafe to try and protect your children and are now trying to figure out where to go and what to do.

This scenario hopefully gives you an appreciation for how important it is to value and respect children when we’re observing them. Often we see children when they’re vulnerable, for example, if they’re crying because they’re terrified during their first day of school or if they’re screaming out of frustration that another child just ripped their painting. As we consider the ethics of observing children, we need to be mindful of when we choose to observe children, why we select those times, and what our purpose is. Also, ask yourself, “How would I feel if I were that child, having everything I said and did captured by someone else without my permission?”

Educators inherently have an ethic of care to treat students fairly, with respect and with dignity. Vulnerable groups require additional consideration, including those who are socially, economically or politically marginalized, including…children, those with disabilities or mental health considerations. When sharing documentation, special attention should be paid to ensure that vulnerable people are not negatively represented and/or impacted. (Ontario Ministry of Education, 2015, p. 7).

We all have the right to experience emotions privately without feeling that someone might be taking a picture of us or writing down their observations during a vulnerable time.

Recognizing your Biases

If you search for the word “bias,” this is what pops up: “prejudice in favour of or against one thing, person, or group compared with another, usually in a way considered to be unfair.”

We all have biases because they stem from our upbringing. Every interaction and every experience we have had has shaped who we are and how we see the world. To some degree, our biases influence our beliefs and behaviours, they sway our attitudes, and they affect our personalities. Because our biases are so ingrained into who we are, it would be unrealistic to simply try to ignore our biases. Therefore, a valuable exercise might be to do a self-check and examine your own biases. Look for those biases that are “triggers.” More specifically, think about the behaviors, temperamental traits, and moods that make you feel uncomfortable, frustrated, or annoyed.

It is important to note, that we might not be fully aware of all our biases. For example, when a child says, “give me some milk!” our first response might be “Ummm, how do you ask?” We might not realize that manners (or lack thereof) can make us react in a judgmental way. What’s important to recognize is that how we feel about the child’s behaviour can taint how we see them. What’s more, our biases can influence how we gather our observation evidence. As intentional educators we have to recognize our biases so we can treat all children with the respect that they deserve. According to NAEYC’s Code of Ethical Conduct and Statement of Commitment (2011).

We shall not participate in practices that discriminate against children by denying benefits, giving special advantages, or excluding them from programs or activities on the basis of their sex, race, national origin, immigration status, preferred home language, religious beliefs, medical condition, disability, or the marital status/family structure, sexual orientation, or religious beliefs or other affiliations of their families. (p. 3).

So as not to lose our objectivity, it is important to keep an open heart, an open mind, and a clear lens. Rather than letting a child’s behaviour trigger you, look beyond their behaviour, and look beyond your bias. Focus on collecting objective observation evidence and use that data to reflect on what might be causing that behaviour. Consider ways that you can support the child through redirection, modelling, scaffolding or positive reinforcements. As intentional educators, one of our primary roles is to empower children, and to build meaningful relationships by creating warm, caring environments (Epstein, 2007).

Social Media

In today’s technology-driven society, social media is everywhere. It only takes a few quick clicks to upload a picture and share it with others. On one hand, this is very helpful in keeping friends and family updated on our lives, but in an early learning setting, we need to be extremely careful about how we use social media. Many early learning programs use specific websites or apps to share information and pictures with families, and these are password-protected and only available to families registered in the program. To protect children’s identities and respect families’ privacy, we must only post children’s information on those pre-approved sites, and only when the families have consented to that specific form of sharing. If educators have their own personal social media accounts, pictures of the children must never be posted.

Something else to consider is the device that is used to take children’s pictures that will be posted on the program’s social media. If educators are only permitted to use a specific camera or iPad to take pictures, they must never use their own personal camera or phones to document children’s learning.

Ponder This

How do you, or how would you feel if you saw photos of yourself where you did not give consent?

Besides what has been discussed about confidentiality with media, what legal issues need to be considered?

General Guidelines

As we come to the end of this topic, here are some guidelines to ensure your observations are ethical, respectful, and protect children’s and families’ rights and values.

- Take every precaution to maintain confidentiality and to ensure privacy

- Remember to ask if it is OK to take photographs of children and their work

- Understand that children have the right not to take part in activities

- Be respectful and keep a reasonable amount of space between you and the child so as not to interfere with their play and learning

- Be attuned to children’s body language, temperament and styles of communication

- See each child as a unique individual who has their own perspective, set of feelings, interests, and way of socializing, along with their own cultural context, belief system, and values

- Be upfront and inform children about the purpose of your observation if you are approached

- Share information with the child about what you have observed when appropriate

- Write quotes down just as they were said without adding context, or trying to rationalize what the child may have meant

- Be aware that photos and observation data should be collected in a non-intrusive manner

- Ensure that observation evidence and photos are used only for the purposes intended

- Handle photos and data with care and sensitivity, and always store information securely

- Realize that a child’s reactions, behaviours and conversations may not be what you expect and therefore you should refrain from being judgmental or tainted by your cultural biases

By following these guidelines, you are providing the children you observe with the respect they deserve while ensuring their dignity and safety. The centres and programs where you are visiting, completing your placements, or working are trusting you to act with integrity while you are observing their children. Lastly, families will appreciate that you have their child’s best interest at heart.

ethical standards

Following established code of ethics and standards of practice encourages observers to be mindful when observing and documenting. Educators are are responsible for adhering to ethical and occupational standards specific to observing and creating documentation. The College of Early Childhood Educators regulates and governs Ontario’s registered early childhood educators -RECE- in the public interest. The Code of Ethics and Standards of Practice reflects the profession’s core set of beliefs and values of care, respect, trust and integrity.

Wrap it Up

It is important to explain to families that observations are part of your practice, and as a student your studies. Written consent needs to be given before observations commence and confidentiality forms signed. Pedagogical documentation, particularly when observing young children, involves navigating a complex landscape of ethical considerations across philosophical, practical, and policy dimensions.