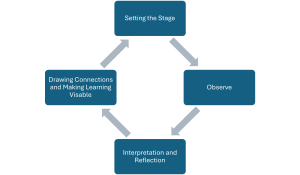

4 The Cycle of Observation

When we observe children, it isn’t just an isolated event; observing children is an in-depth process that happens in a cycle. In this chapter, we’ll take a look at the different steps in the cycle.

Step 1: Setting the Stage

In step 1 is when we get ready to observe and document. We can certainly just observe children spontaneously, but we should be prepared to document our observations so we are always ready.

An intentional educator is a prepared educator, so here are a few things to organize before observing and documenting children’s learning:

- Something to write on – paper, sticky notes, colour-coded index cards, clipboard, notebook

- Something to write with – coloured ink pens, sharpie markers

- Something to record with – phone, tablet, printer

- Something to store your documentation in – a filing cabinet, accordion file folder, portfolio, application, server, cloud

- Blank observation tool templates – checklists, frequency counts, ABC, anecdotal notes (we will learn all about these in an upcoming chapter)

- Some extras – tape, stickers, paper clips, labels, charger cables

Ponder This

How can you complete observations while still being hands on and engaged with young children?

Will the way you document impact their play?

How does the early learning environment affect your ability to observe?

Step 2: Observe

This next step is when the observation takes place. You might be wondering how to know when to observe children. What is important? What kinds of moments should we try to capture? There isn’t a straightforward answer to this question, but let’s consider some general guidelines to help you decide when to observe children.

A New Appreciative Inquiry: We might have no specific reason to observe a child other than wanting to learn more about them, including their interests and development, and that’s perfectly fine! This is often the reason why we observe children who are new to a program.

A Previous Appreciative Inquiry: Perhaps we have previously observed a child and want to follow up to see how their skills have developed or how their interests may have evolved since the last observation. The child might be working on a specific skill that requires some support, so in these situations, we would want to observe the child relatively often to determine whether we can decrease the amount of support as the child becomes increasingly more competent.

Response to an Invitation: One way that we can learn more about a child is to observe how they respond to something in the environment which can help us determine a child’s interests. For example, we may decide to put out some gems, small pebbles, fresh flowers, and a mirror to see what children choose to do with the materials.

A Question or Wondering: There might be something specific that we want to know about a child. For instance, perhaps we have noticed that James always chooses to play in the block area, so we’re curious about what kind of structures he builds, what he knows about different kinds of buildings, what strategies he uses, and whether he is open to collaborating with other children or prefers to build by himself. We might also wonder whether a child needs additional support in a certain area that we’re hoping to answer through observation.

Here are some examples of questions and wonderings that might guide your next observation:

- “In what ways are the children using the new materials in the block area?”

- “Which children can cut a zig-zag line with scissors?”

- “Who will recognize their name tag that is posted on the outside table?”

- “Will Sofia play with a peer today or keep to herself?”

- “I wonder how Jackson will do at drop-off today.”

- “I’m curious how the children will react to painting with fall leaves and who will try.

- “What activity area are the children using the most while outside?”

Indigenous Perspective

Five components of Indigenous Knowledge that are important to know for those engaging in practice, programming, research, evaluation, and observation with Indigenous children, youth, and families.

Indigenous Knowledge is based on millennia of observations

Observations have been documented for generations in Indigenous Peoples’ stories, songs, place names, values, and languages and passed down intergenerationally to children and youth as they grow. This teaches children and connects them to their ancestors as well as future generations. Generation after generation of Indigenous Peoples have further accumulated and refined their Knowledges through life experience.

Indigenous Knowledge is temporal and place-based

An understanding of what has changed over time. This Knowledge is necessary for survival through adaptation. Indigenous people are land-based and their Knowledge is grounded in what they see around them

Indigenous Knowledge is living

Intergenerational and grounded in evidence through observation; as a result, it is living and not static. As people observe and learn, their Peoples’ body of Knowledge grows, and they change their behavior based on the new knowledge.

Indigenous Knowledge is kinship-based

Nothing is objective or alone. All things are in interaction with one another, including humans and the natural world. Instead of being separate, Indigenous Peoples understand relationality through kinship and an understanding that plants, waters, trees, lands, and animals are relatives and ancestors.

Indigenous Knowledge is wholistic

These are based on each Peoples’ ways of knowing; their understandings of nature and human existence; and the values, value judgements, and ethics they have accumulated over years of survival and relational existence.

adapted from: Gordon, H.S.J. (2023). 5 things to know about Indigenous Knowledge when working with Indigenous children, youth, and families. Child Trends. https://doi.org/10.56417/3504n5609v

Step 3: Interpretation and Reflection

Once we observe children, we then need to figure out what it all means. For instance, if we notice that James always builds castles in the block area and only builds by himself, turning down invitations from other children to build together, what’s next? What does that all mean, and how should we respond? These questions are asked in this stage when we interpret our observations and reflect on the significance of them. This is a bit of a complex task and will be explored in more detail in an upcoming chapter. During this step, we can collaborate with other educators and the children’s families since their perspectives and knowledge might provide some valuable insight. We can even speak with children themselves to help us understand their thinking.

Pin It

interpretation – definition- a teaching technique that combines factual with stimulating explanatory information.

reflection – definition- a thought, idea, or opinion formed or a remark made, consideration of some subject matter, idea, or purpose.

insight – definition- the power or act of seeing into a situation

Merriam-Webster.com Dictionary, Merriam-Webster, https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary

Step 4: Drawing Connections and Making Learning Visible

In this step, we need to document our observations, interpretations, and reflections. There are different ways we can do this and guidelines to keep in mind, which we will explore in an upcoming chapter, but essentially, this is when we make children’s learning visible by writing down what we saw, adding a caption to a picture we took, writing a note on the back of a child’s drawing, etc. We make connections between our own interpretations and reflections and insights we gleaned from other educators, the families, and the children. Once we have documented our observations, we will then respond to what we observed, often by creating new learning experiences for children to engage in that either extend their interests or help them further develop a particular skill, and the cycle starts all over again because we will want to observe and reflect on that new experience to figure out how their interests/development have changed and how we can best support their learning from that point. And then we’ll want to observe again… You get the idea!

Wrap it Up

We recognize that observing children involves more than just watching them. It is an ongoing process that encompasses 4 key steps- setting the stage, observing, interpretation and reflection, drawing connections and making learning visible. Making learning visible for children and families is about helping them recognize and understand their own learning processes and progress. This approach supports child, family and educator engagement and self-awareness.