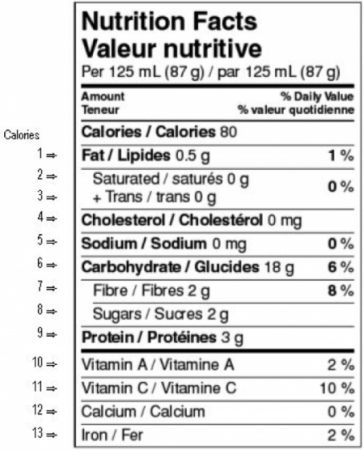

2 The Nutrition Facts Table

Under Government of Canada regulations, the nutrition facts table (NFT) must provide serving size, calories, and 13 core nutrients, including fat, sodium, and sugar (Figure 2). The list of micronutrients, which includes cholesterol, folate, magnesium, niacin, phosphorus, potassium, riboflavin, selenium, thiamine, vitamin B12, vitamin B6, vitamin D, vitamin E, zinc, and other vitamins and minerals, is optional (Health Canada, 2004a). Reading and understanding the NFT is essential for choosing food products that meet the dietary needs of individuals. It is important to consider the % DV and to understand what “less than 5% DV” and “15% DV” mean. For an interactive NFT, visit the Health Canada website.

The NFT displays the % DV so consumers can determine the amount of a certain nutrient in one serving. The list of ingredients is mandatory on most packaged foods that contain more than one ingredient, and ingredients are listed in order of weight. In general, it is mandatory to show both official languages of Canada (French and English) on labels, with some exceptions (e.g., specialty foods, local foods, test market foods, and shipping containers) as long as the products are not resold to consumers.

Allergens

“Allergen Declarations and Gluten Sources” is the declaration on the label that includes the top 10 priority food allergens. They are set by Health Canada and include egg, soy, sesame seeds, milk, seafood, tree nuts (including peanuts), sulphites, wheat, and mustard. If any of these priority food allergens are present, they must be listed in the ingredients and/or in a statement that begins with “contains” or “may contain” on a food product label. It is prudent for any consumer to read the food labels, and it is paramount for a person who either has allergies, or produces food for someone with allergies. Note that companies can change ingredients without telling consumers, thus the responsibility remains with the consumer or end user to read labels.

Best Before and Expiry Dates

The best before date indicates the anticipated amount of time an unopened food product keeps its freshness, taste, nutritional value, or any other qualities claimed by the company, when stored properly and unopened. As soon as the product is opened, the best before date no longer applies. In addition, the best before date does not guarantee product safety.

The best before date must appear on packaged foods that have a shelf life of 90 days or less such as milk, yogurt, or bread. Best before date products still can be purchased or eaten after these dates.

Packaged foods that show an expiration date must be consumed before that date or discarded after the expiry date. The expiry date must not be mistaken for the best before date.

Food packaging plays an important part in the food industry; it keeps the products fresh, prevents them from becoming contaminated, and inhibits bacteria growth. As stated by Health Canada, “all materials used for packaging foods is controlled under Division 23 of the Food and Drugs Act and Regulations, Section B.23.001 of which prohibits the sale of foods in packages that may impart harmful substances to their contents. This regulation puts the onus clearly on the food seller (manufacturer, distributor, etc.) to ensure that any packaging material that is used in the sale of food products will meet that requirement” (Health Canada, 2010, September 9).

Other Claims on Food Labels

The Canadian Food Inspection Agency (CFIA) requires that packaged goods, including baked products, be pulled off the shelves if their labels are missing ingredients or have misleading information. Baked products such as whole grain bread and whole wheat bread must be labelled as such. What constitutes whole wheat bread in Canada? The definition of whole wheat breads states that, “under the Food and Drug Regulations, up to 5% of the kernel can be removed to help reduce rancidity and prolong the shelf life of whole wheat flour. The portion of the kernel that is removed for this purpose contains much of the germ and some of the bran. However, according to the American Association for Cereal Chemists International definition, it is only when all parts of the kernel are used in the same relative proportions as they exist in the original kernel, that the flour can be considered whole grain” (Health Canada, 2007). In addition, claims about the composition of a food product must be identifed. This section of a food label is voluntary, but a company may choose to highlight or emphasize an ingredient or flavour in a product, such as no added preservatives or artificial flavours, or “made with 100% fruit juice.” Such claims do not guarantee that there are no food additives present in a product. Food additives, food colourings, gelling agents, bleaching, maturing or dough conditioners (e.g., azodicarbonamide), which is banned in some countries, and emulsifying agents in amounts not exceeding government guidelines do not need to be listed. A complete list of allowable additives is available on Health Canada’s website. Many foods are exempt from declaration when used as ingredients in other foods; however, exempt components that contain any allergen, gluten source, or sulphites must be declared.

The Canadian Food Inspection Agency states that components “may be declared in the list immediately in parentheses after the ingredient which they are component of or in the ‘Contains’ statement immediately following the list of ingredients. If nutrients components are also required to be declared by section D.01>007 (1) (a) and D.02005, the nutrient components should be declared in separate brackets after the allergen, gluten source or sulphite declarations. For example: enriched flour (wheat), (niacin, thiamine, riboflavin, iron) or wheat flour (niacin, thiamine, riboflavin, iron).” (Canadian Food Inspection Agency, 2013).

Compliance with Labelling Regulations

Only nutrition facts and the ingredient list are mandatory in Canada. The nutrition facts table (NFT) includes the “specific amount of food on which all nutrient information is based: calories and 13 core nutrients; the actual amount of a nutrient, in grams or milligrams; the % Daily Value” (Health Canada, 2015). Although the NFT is helpful for consumers making informed food choices, it is the food manufacturer (i.e., baker/business owner) who needs to be in compliance with the labelling regulations. Customers must take caution when reading health facts, in particular if a product lists certain health claims that may be based on marketing schemes and or sales promotions. A recent documentary broadcasted on CBC Marketplace investigated food product labels. See the story, “Food fiction.”

Nutrition and Health Claims

Nutrition and health claims, when made, must follow specific rules from Health Canada to ensure the claims are consistent and not misleading. A nutrient claim may provide information on calorie counts, or on whether a product is a “good source of fibre” or “trans fat free.” Other nutrition claims may inform consumers if a product is high in calcium. A health claim on labels promotes or claims health effects of certain foods (e.g., “a healthy diet rich in fruit and vegetables may help to reduce the risk of some types of cancer”). Health or nutrition claims of products must meet specific criteria determined by Health Canada regulations. In order to “use these nutrition claims, the food product must meet specific criteria.”

For example:

- for “sodium free,” the product must have less than 5 mg of sodium per specific amount of food and per a pre-set amount of food specified in the regulations, the reference amount;

- in order to be able to say the product is “low in fat,” the product must have 3 g or less of fat per specific amount of food and per reference amount. (Health Canada, 2015).

Methods of Production

Methods of production claims are voluntary and provide information about how products where grown, produced, or handled. Such claims provide consumers with information on how cattle were raised, fed, transported, or slaughtered and whether they were given growth hormones or antibiotics. Other claims may show whether eggs are organic or free range, and the type of feed given to the hens. All claims must be truthful and not misleading, and are required to meet additional criteria.

Country of Origin

If a product is imported from another country, its country of origin must be on the label. If products are produced in Canada, they must include the name and address of the responsible company. Food products that say “Product of Canada” must follow specific guidelines. For example, a “Product of Canada” must have most (generally 98%) of its food, processes, and labour originating in Canada. This means these foods were grown or raised by Canadian farmers, and are prepared and packaged by Canadian food companies.

[The] claim “Made in Canada” means that the manufacturing or processing of the food occurred in Canada. A claim can be made on a label if the last substantial step of the product occurred in Canada, regardless if the ingredients are domestic or imported. For example, the processing of cheese, dough, sauce, and other ingredients to create a pizza would be considered a substantial step. If the food product contains some food grown by Canadian farmers, it can use the claim “Made in Canada” with domestic and imported ingredients. If all of the ingredients have been imported, it can use the claim “Made in Canada” from imported ingredients. All other origin claims such as “Distilled in Canada”, “Roasted in the United States”, and “Refined in France” that describe the country’s value-added may be used as long as they are truthful and not misleading for consumers. (Canadian Food Inspection Agency, 2015d).

Consumers play an important role in food labelling in that they make an effort to read and understand the labels of all the food products they buy. If questions arise and more information on a product is needed, consumers should get in touch with the company directly. However, if there are any safety concerns or apprehensions about an unlabelled allergen, the complaint needs to be reported to Canadian Food Inspection Agency (CFIA).

Other processes such as high pressure processes (HPP) where foods have gone through high pressure processing exposure of “87,000 psi/600 MPa for up to 9 minutes does not cause a significant compositional change in the treated food, nor have there been any safety concerns raised regarding the use of this process for fruit and vegetable-based juices. On this basis, mandatory labelling requirements are not necessary in this case” (Health Canada, Food and Nutrition, 2015).