2 Types and Variability within Illness Trajectories

The trouble with always trying to preserve the health of the body is that it is so difficult to do without destroying the health of the mind.

-G.K. Chesterton

Learning Objectives

- Define illness trajectory.

- Identify the four most common illness trajectories.

- Describe the relationship of illness trajectories to hospice care.

- Explain the importance understanding patterns of illness for individual patients.

Most nurses learn about the term “illness trajectory” at some point during their nursing program. In loose terms, trajectory means “course,” and therefore illness trajectory means “course of illness.” By understanding which type of illness trajectory a patient has, it will help to provide answers for two important and common questions many patients have: “How long do I have?” and “What will happen?” (Murray, Kendall, Boyd, & Sheikh, 2005). Understanding the usual course of illness includes both the expected time frame until death and also what the patient can expect will happen with the illness’ progression. Often the length of time is less important for patients then what will happen during their upcoming days. In order for patients to prepare, many want to know what the end of life will be like. Although each patient’s illness and subsequent death can differ, you will see patterns in those final days of life. The illness trajectory largely determines these commonalities. Although not everyone will fit into a specific illness trajectory prognosis, trajectories help both patient and nurse plan for the care needs of the patient. It is far better for the patient to know about, and be prepared for, what might happen.

In the late 1960s, two researchers by the names of Glaser and Strauss (Glaser & Strauss, 1968) wrote about three different trajectories that people who are dying experience. These include: surprise deaths, expected deaths, and entry-reentry deaths. Surprise deaths are those that are unexpected and usually happen without prior warning, such as a motor vehicle accident. Expected deaths are those that are with people who have some type of terminal illness in which their death is not a surprise and is expected with usual course of disease progression. Entry-reentry deaths are used to describe persons whose illness trajectory is slower but they have periods of hospitalization and periods of better health. Glaser and Strauss were the first to begin to identify and describe these trajectories of how people die. Additionally, they studied dying people and learned a great deal about how people who are dying feel about what is happening to them. (Refer to Chapter 3 for more information regarding this and other frameworks used to describe how people with serious illnesses perceive their health.)

Types of Illness Trajectories

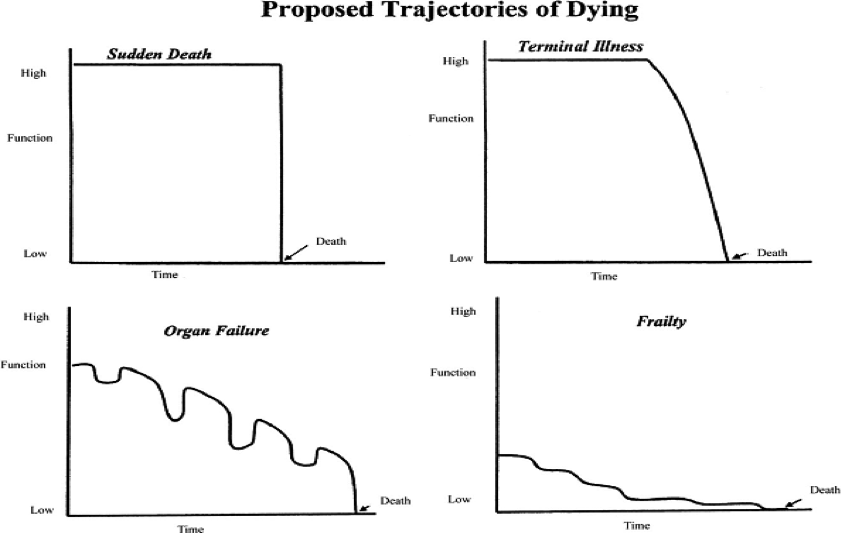

Although Glaser & Strauss were the first to identify trajectories of dying, much work has been done since their initial description. These trajectories can also be referred to as illness trajectories. June Lunney and colleagues (Lunney, Lynn, & Hogan, 2002) used data from Medicare decedents and proposed the following four trajectories (Figure 2.1) as the most common patterns of illness progression:

- Sudden death

- Terminal illness

- Organ failure

- Frailty

Sudden death

This trajectory is characterized by no prior warning or knowledge that death is imminent. People are at a high or normal level of functioning right until death occurs. This is most common with accidents and other unexpected deaths.

Terminal illness

This trajectory is most common among patients living with an illness that can be categorized as leading to terminal, such as cancer. Functioning remains fairly high throughout the course of illness and then patients rapidly decline weeks or sometimes even days before death. Hospice care was developed based on this type of trajectory, which will be discussed in the next section.

Organ failure

This trajectory is very common among many people in this country who live with a chronic illness which will eventually progress to death. Heart failure and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease are the most common illnesses that follow this type of progression. These illnesses can also be known as exacerbating-remitting, which simply means that they experience periodic exacerbations (flare-ups or worsening) of their illness which often leads to hospitalization. The symptoms eventually improve but over time, there is a gradual decline in the overall health of these individuals. Patients with this type of trajectory, particularly those with heart failure, have an increased risk for sudden cardiac death (Tomaselli & Zipes, 2004).

Frailty

This trajectory is characterized by a slow decline towards death with low functional ability through the majority of their illness. These patients often live with progressive disability and require maximum assistance and care for a long period of time before their death. Patients with a general frailty and decline of all systems, such as with older adults afflicted with multiple conditions, can be categorized with this pattern. Patients diagnosed with dementia or Alzheimer’s disease also have a prolonged period of decline and low level of functioning. Patients with this type of trajectory often die from complications associated with being totally dependent in all activities of daily living. They have also been found to have higher rates of pressure ulcers and pneumonia from being bedbound and with prolonged use of feeding tubes (Rhodes, 2014).

As mentioned before, it is important for nurses to have an understanding of which trajectory describes their patient’s illness. Each of these trajectories will vary in their overall course and presentation and a basic understanding about how they differ will be helpful for the nurse to be able to plan individualized care for their patient. In addition, it is important to understand the common experiences of people living with these various trajectories and the experiences of the family members who care for them. Nurses who care for patients at the end of life should have a basic understanding of the concerns common to people with certain types of illnesses. This will help the nurse better prepare for the care needs of these patients and their families.

Illness Trajectories and Hospice

Hospice enrollment is structured by policy, both related to governing reimbursement agencies such as Medicare and Medicaid, and also within the individual hospice agency (Scala-Foley, Caruso, Archer, & Reinhard, 2004; Lorenz, Asch, Rosenfeld, Liu, & Ettner, 2004). Historically, the Medicare hospice benefit was structured to fit a specific type of problem—the illness trajectory of those afflicted with cancer (National Health Policy Forum, 2008). This is described as the terminal illness trajectory in Figure 2.1. As the decades have progressed, the scope of end-of-life care has expanded and includes patients with other types of trajectories that are different, such as patients with chronic illnesses, such as heart failure.

Since hospice care in this country was developed based on the terminal illness trajectory, many of the rules and regulations that govern the Medicare hospice benefit do not meet the needs of patients who are afflicted with an illness depicted by one of the other trajectories. For instance, the goal of hospice is to improve a person’s quality of life through adequate management of symptoms. In patients with a terminal illness trajectory, many of the medications used to manage adverse symptoms are those to treat pain and anxiety. In patients with an organ failure trajectory, many of the medications that are used to manage symptoms are not pain medications, but medications to reduce the workload of their heart and/or reduce the fluid build-up around their heart. The current hospice benefit reimburses specific medications for use in hospice, with pain and anxiety medications being the most common. Other medications that are used for symptom management in illnesses, such as heart failure, are often not reimbursed with hospice because they are considered curative medications, rather than medications used for symptom management. So in trajectories such as this one, the medications that are used to manage the symptoms associated with the illness are not covered or allowed with the hospice benefits. This dissuades many individuals afflicted with non-cancer illness trajectories from electing hospice care. To date, there have been no substantial changes made to this policy to allow it to fit those other illness trajectories very well.

Currently, prognosis and patient preference are part of the main inclusion criteria that have to be in place in order for people to access the Medicare Hospice Benefit. The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services have designated four conditions that need to be met for an individual to be covered under the Medicare Hospice Benefit: (a) the individual must be eligible for Medicare Part A, (b) the individual must be certified as having a terminal illness with a 6-month or less prognosis if the illness runs its usual course, (c) hospice care must be received from a Medicare-certified hospice provider, and (d) the individual must waive their right to all Medicare payments for curative care, electing only comfort care through hospice (Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, 2013).

An Understanding of Illness Trajectories in Nursing Care

So now that you have a basic understanding about illness trajectories, how can that knowledge be used when planning and implementing care for your patients? Although the nurse will not typically be the clinician who provides prognostic information to the patient answering the question “How long do I have?”, you should be prepared to address the question “What will happen?” Educating the patient and family does not stop during end-of-life care. There will be many areas that patients and families will need to learn about in order to promote the best quality of life. In addition to teaching patients about various medications used for symptom management, strategies to address nutrition and hydration needs, and a host of other topics, the nurse should be able to tell patients what they might expect over the next few months, weeks or days, if applicable. This can include both physiological and psychological signs and symptoms, in addition to practical aspects of how their activities of daily living will change and what kinds of care they should anticipate they might require.

Some patients and families may want to know every detail about what to expect, including how their death might actually happen. Others might prefer to know this information in smaller doses, as they begin to exhibit signs and symptoms that would require patient care teaching. It is very important to ascertain the patient’s desire for this information including level of detail. It is not wise to delve in to very detailed accounts of the dying process very early on, as this may frighten the patient and cause undue anxiety. If, however, patients want to know, the nurse should provide that information in a sensitive manner. There is a plethora of educational brochures and information available on this topic. Nurses should check with their institutions to obtain educational materials to have on hand to give to patients as the time arises. Now we will go through some commonalities that patients and families may experience with each of the four illness trajectories.

Sudden death

With this illness trajectory, you might or might not have provided any care to the patient who has suddenly died. You may be the nurse in the Emergency Department who was assigned to the patient who had already died in route to the hospital or whose death had been called following an unsuccessful code. If the patient is alive at the time of the interaction, the nurse must be sure to provide as much support and comfort as they can in the midst of the likely chaos that will be happening. The nurse must never forget that their patient is an actual individual with a life and a family, as they are busily working with the health care team to save his or her life. As things may progress, the nurse should take time to let the patient know what is being done and that they are not alone. Instead of just standing in the corner as other clinicians perform cardio-pulmonary resuscitation on the patient, the nurse should proceed to the head of the bed and provide reassurance that they are present with the patient. Often the patient may be unconscious at that point, but we cannot say with certainty what they can or cannot hear, so be mindful of what is said during that period of time. Following the death, be sure to provide respect and dignity during post-mortem care. Communicating with the family of a deceased patient can be one of the most challenging and difficult encounters a nurse will experience, as with a sudden type of illness trajectory the death was not expected. This means that the family was likely not present or with the patient before or at the time of death, depending on the policy that governs family presence at the bedside within your institution. There can be a lot of emotional and psychological stressors associated with the family members of patients with this type of death. Family members might not have been able to say their goodbyes or to mend any differences before their loved one died. There might be guilt associated with this; and if family members were also involved in an accident and survived, they may experience survivor’s guilt. Survivor’s guilt is a common reaction to a sudden and/or traumatic loss in which the person left behind feels guilt that they survived and their loved one did not (International Society for Traumatic Stress Studies, 2005). Families experiencing difficulty coping after the sudden death of their loved one often have alterations in the normal grieving process and may likely need to seek assistance in helping deal with the loss.

Terminal illness

Patients with this type of trajectory usually have some type of cancer. Their decline is typically short, often only a few weeks or days before they die. As you can see in Figure 2.1, the patient remains at a high level of function until that sudden sharp decline before death. One of the most important pieces of information that a nurse can give patients and families with this type of trajectory is that the end of life often comes quickly, without much warning. Most patients who are living with cancer receive treatment and diagnostic testing, followed sometimes by a break and then more treatment, and the cycle continues until the cancer goes into remission. If the cancer is at an advanced stage, there may be no break in treatment. Patients with end-stage cancer will usually continue their treatments until all curative options are exhausted, their lab values indicate that they are unable to receive further treatment due to low blood counts, or their cancer progresses despite all of the before mentioned interventions. It is often at the point at which the patient is informed that the cancer is spreading, or that there are no other treatment options, that the terminal decline towards death begins to happen. The important factor to explain to patients and families is that a person can be alright one day (or at least holding his own) and then bedbound the next day and actively dying. Thus the period of decline and disability is rapid and often chaotic if patients and families are uninformed that this commonly happens with this type of trajectory. Families of patients with this trajectory often take on the role of caregiver quickly and are usually aware that death is nearing and have the time to make amends and say good-bye. Taking on the caregiver role during this time instead of just being the patient’s spouse or son or daughter can cause emotional distress in family members. Depending on the setting, you can try to offer assistance with basic caregiving tasks, or perhaps institute a nursing assistant or tech to help the patient with those needs. This will help the family member to just be with the patient as the family member rather than as the caregiver.

Organ failure

This type of trajectory may be the most common you will see in acute care settings. This trajectory is characterized by chronic and progressive illnesses that have periodic exacerbations that frequently result in inpatient hospitalization. Patients with this type of trajectory live with their illness for several years and go through many ups and downs during that time. Although patients recover from their exacerbation and get discharged from the hospital, there is a gradual decline in functional status over the years. So with each exacerbation, patients never really return to the same level of function they were previously. Over time, these exacerbations become more frequent and patients have more difficulty bouncing back. There is much difficulty with prognostication among these patients, as even experienced physicians cannot say with certainty if patients are at the end of life. Additionally, many of the medications that these patients receive for symptom management during an exacerbation are considered to be curative and are not covered by the current Medicare hospice benefit. This factor detours some patients with this type of trajectory from electing to have hospice care.

Educating patients and families is very important because these patients usually have a higher risk of sudden death (particularly with a cardiac diagnosis). These patients are also used to going to the hospital to get “fixed up” for exacerbations. Since this illness trajectory has a less predictable course than other trajectories, we never know if the next exacerbation could be the last. Assessing whether patients have an advance directive is very important because of the unpredictability of this type of trajectory. Since prognosis is not commonly talked about with these types of illnesses, patients might not be aware of their options and perhaps have not considered making an advance directive. Additionally, the risk of death following an exacerbation is great for this type of trajectory and often, as mentioned before, unexpected. Families may have a difficult time understanding why their loved one did not bounce back this time. It is important to educate patients and families about illness progression with this type of trajectory in a way that informs them but does not completely rob them of hope.

Frailty

Patients who have this type of trajectory often live with their illnesses for many years. Illnesses that comprise this progression often disable patients early on and patients live with a low level of functioning for many years, requiring maximum assistance. This assistance and care is usually provided by family members and/or patients become institutionalized in long term care facilities. Caregiver burnout is often a problem and family members require a lot of emotional support as well as practical support and assistance. Offering any type of community resource or respite care for these families can be a great deal of help. Patients themselves might be afflicted with cognitive impairments which can lead to many adverse events. Most require assistance in most activities of their daily living.

Patients with this type of trajectory may get to a point in which they are no longer able to swallow and require artificial means of nutrition and hydration. The use of feeding tubes is a sensitive subject and can cause many ethical dilemmas for healthcare personnel and families alike (Rhodes, 2014). Often helping families evaluate the quality of life of their loved ones is one way that nurses can help families with their decision making about whether a feeding tube is appropriate. Families often struggle with caring for their afflicted loved ones for many years and the nurse should always keep this in mind when planning and implementing care for these types of patients.

What You Should Know

- By understanding illness trajectories, the nurse will be able to develop an individualized plan of care for the patient who is nearing the end of life.

- Sudden death, terminal illness, organ failure, and frailty are the four most common types of illness trajectories found in end-of-life care.

- The current Medicare hospice benefit was developed based on a terminal illness type trajectory and its regulations may not be as well suited for patients with other illness trajectories.

References

Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. (2013). Medicare hospice benefits. Retrieved from http://www.medicare.gov/pubs/pdf/02154.pdf

Glaser, B. G. & Strauss, A. L. (1965). Awareness of dying. New Brunswick: Aldine Transaction.

International Society for Traumatic Stress Studies. (2005). Trauma, loss and traumatic grief. Retrieved from http://www.istss.org

Lorenz, K. A., Asch, S. M., Rosenfeld, K. E., Liu, H., & Ettner, S. L. (2004). Hospice admission practices: Where does hospice fit in the continuum of care? Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 52, 725-730.

Lunney, J. R., Lynn, J., Hogan, C. (2002). Profiles of older Medicare decedents. Journal of American Geriatrics Society, 50, 1108-1112.

Murray, S. A., Kendall, M., Boyd, K., & Sheikh, A. (2005). Illness trajectories and palliative care. BMJ, 330, 1007-1011.

National Health Policy Forum. (2008). Medicare’s hospice benefit: In the spotlight. Retrieved from http://www.nhpf.org/library/forum-sessions/FS_08-01-08_MedicareHospice.pdf

Rhodes, R. (2014). When evidence clashes with emotion: Feeding tubes in advanced dementia. Annals of Long Term Care, 22(9), 11-19.

Scala-Foley, M. A., Caruso, J. T., Archer, D. J. & Reinhard, S. C. (2004). Medicare’s hospice benefits: When cure is no longer the goal, Medicare will cover palliative care. American Journal of Nursing, 104, 66-67.

Tomaselli, G.F. & Zipes, D.P. (2004). What causes sudden death in heart failure? Circulation Research, 95, 754-763.