4.2 Frequently Asked Questions

Suzan Last

{1} Gathering, analyzing, and synthesizing research assures others that what you have to say is built on credible and accepted grounds. Readers will want to know where you have found your source material not only to ensure that it says or demonstrates what you’ve alleged it does, but also to ensure that it is credible, relevant, and authoritative. One reference to an obscure journal source is unlikely to prove as convincing as one to a leading journal or, better, to several journals and books in the field. Citation styles, of which there are several, provide readers with consistent, user-friendly information to access your source material. The choice of a style is typically dependent on the field of study. Competent use of a style empowers readers to locate your sources.

1. What is IEEE Style and why do I need to use it?

{2} The Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers (IEEE) Style is one of many systems for referencing (citing and documenting) sources that you have quoted, paraphrased, or summarized in your documents or presentations. Different disciplines use different styles. Table 4.2.1 identifies the most common styles for several academic disciplines.

Table 4.2.1: Typical citation styles by academic discipline

| DISCIPLINE | CITATION STYLE |

| Engineering (computer, civil and construction, electrical and electronics, mechanical, photonics) | IEEE or APA |

| Social sciences (economics, politics, psychology, sociology) | APA |

| Humanities (English, philosophy, history) | MLA or Chicago/Turabian |

| Natural sciences (biology, chemistry, physics) | CSE |

| Health sciences (dentistry, kinesiology, medical, nursing) | APA or Vancouver |

{3} IEEE is the preferred citation and referencing style used for engineering technician and technologist programs at Niagara College, including civil, computer, construction, electrical, electronics, mechanical, and photonics. Compared with most of the other systems, the chief difference students will notice is that IEEE uses a numerical organization of reference list entries rather than an alphabetical list that uses an author’s last name. In-text citations are themselves numerical as you will see.

{4} In your assignments, you often have to gather information, data, illustrations, theories, interpretations and facts. These sources often provide the evidence or theoretical framework you need to support and develop your ideas. You must cite all information and images that you retrieve from other sources to assure readers of the quality of your research and to give credit for the ideas and information to the original author. Failing to cite a source—whether quoted, paraphrased or summarized—is plagiarism. Citing your sources correctly has the following benefits:

- Provides evidence you need to support your claims and validate ideas

- Shows you have done significant reading and research on your topic, and therefore have a credible level of authority to write or speak on this topic

- Shows that you can synthesize and incorporate information into your own work, combining it with your own ideas; the citations distinguish YOUR ideas from those of your sources

- Allows the reader to find those sources and do further reading

- Allows you to maintain academic integrity (avoid plagiarizing).

2. What are in-text citations and reference list entries?

{5} Citing and referencing sources is a two-part process: (i) an in-text marker or signal directs the reader (ii) to the complete bibliographical reference at the end of the document. Think of the former as a way of letting the reader know that what they have just been reading is taken from (as a summary, paraphrase, or quotation) or is supported by some form of research material. The “Reference” list at the end of your document provides your reader with the tools they need to access the material–it is here that you supply your reader with the information needed (author, title, publication, etc.) to locate your sources for themselves. Both elements, in-text citations and reference list entries, are essential. Moreover, missing one or the other can result in plagiarism.

Key Takeaways

In-text citations

- occur throughout your document

- use a recognizable format to ensure that readers know that you are signalling a source

- alert your reader to the fact that you are using research materials

- follow your use of quotations, paraphrases, summaries, or data and graphics taken from your research materials

Reference list entries

- occur at the end of your document

- provide the reader with complete bibliographic (library/search related) content to enable them to locate your sources

- require that you follow a consistent formatting system to make it easy for your reader to identify the content they need to search for your sources

{6} Formatting and using in-text citations in IEEE is fairly straightforward. IEEE uses a numerical system to document research sources. The numbers appear (a) on the line rather than superscript, (b) inside square brackets, and (c) prior to the end punctuation or period. A comparison might help: the American Psychological Association (APA) uses a parenthetical (rounded brackets) system that includes the author’s last name and the date of publication, so (Ferry, 2022) would alert the reader to a source written by an author with that name published in that year. IEEE simply uses the number in square brackets or [1]. To discover the needed information to locate the source, the reader will have to refer to the reference list at the end of your document, but all they need is the [1] to do so.

{7} Sources are assigned their respective number by the order of use in your document: that is, the first source you use is numbered [1], the second source you use is numbered [2], and so on. Moreover, each source retains the same number throughout the remainder of your document, no matter how many more times you refer to it; so the second source you use, [2], will remain [2] each subsequent time that you refer to material taken from it. The reason for this is that the reference list at the end of your document is numerically organized. Each entry in the list has a unique number identifier that allows your reader to find the source material they are looking for. In contrast, most other citation styles use alphabetically arranged lists that distinguish sources by the last names of authors. Unlike the in-text citations, the requirements for entries in your list of references are more complex, so they will be covered in Section 4.3.

3. In-Text Citations – Where do they go?

{8} It can be tricky to know exactly where to place the in-text citation in your sentence. Generally, the default position for a citation is at the end of the sentence, unless placing it there would create confusion. For example, where should the citation go in the following sentence?

Smith claims that “assume this is a quotation from Smith,” but other scientists argue that her conclusions are flawed.

If you place the citation for Smith at the end of the sentence, you are saying that Smith acknowledges that many scientists think her conclusions are flawed. That wouldn’t make sense. Moreover, you might confuse your reader because you will have to provide citations for the work by the “other scientists” to whom you refer. To avoid any ambiguity, you should place the in-text citations as follows:

Smith claims that “assume this is a quotation from Smith” [1], but other scientists [2]-[5] argue that her conclusions are flawed.

Note that you could also have placed the in-text citations [2]-[5] at the end of the sentence. The key thing is to differentiate for your reader the origin of the material you are citing.

{9} The in-text citation can be located in several places:

- At the end of the sentence, if the entire sentence is a quotation, paraphrase, or summary of your source: Chan asserts ideas X and Y, and he gives additional examples to illustrate them [3].

- Directly after the name of the source: Chan [1] claims…

- Directly after a quotation: Chan asserts that “insert quotation here” [2].

-

- If you include commentary of your own (your analysis of Chan’s assertion, for example), you should place the in-text citation immediately after the quotation. Otherwise, place it at the end of the sentence, and carry on with your idea (your analysis of Chan’s assertion) in the following sentence.

-

- After referring to a source or an idea (in a summary or paraphrase) from a source:

- This theory was first put forward in a 1996 study [4].

- Several recent studies [3], [5], [9]-[12] have suggested that…

{10} The central rule governing the use of quotation marks (“”) in your texts–that is, that everything inside the quotation marks appears as it would in the original, unless otherwise indicated–dictates that your citation should NOT go inside the quotation marks when it is not part of the quotation. However, punctuation must be placed AFTER the citation whenever that citation is part of that sentence (or clause), not part of the next sentence, for example:

- Author X claims “this idea is a quotation” [1]. The next sentence starts here…

- Author X claims “this ideas is a quotation” [1], and I add my interpretation after.

Exceptions to this rule include the use of a question mark or an exclamation in the original text. In such cases, include that punctuation inside the quotation mark, but also include a final end-punctuation mark after the in-text citation. Finally, IEEE’s style guide permits you to use the in-text citation as a noun-substitute, including for the subject of a sentence:

- As [1] and [5] have shown, quantum theory has many practical applications in real world settings. [2] disagrees, however, and argues that ….

This is why you must put the period AFTER the citation when a sentence ends with a citation. A citation that comes AFTER the period technically belongs to the next sentence, as [2] does in the preceding example, where it is the subject of the verb “disagrees”.

4. Do I need to include page numbers in my in-text citations?

{11} For the most part, your in-text citations will almost always consist of just the two parts: the square brackets and numerical reference–[5]. Some IEEE publications, however, require authors to differentiate in-text citations for paraphrases and summaries from those for quotations by including page numbers in the latter. When citing a quotation from a print source, therefore, your citation could indicate the page or pages where that quotation can be found:

- [2, p. 7]

- or, when the quotation carries over to a second page, [2, pp. 7-8]

If the source is from the Internet or does not have pagination, you do not have to indicate page numbers (or paragraph numbers). When citing equations, figures, and appendices, you should also use the same format used for citing page numbers:

- [3, eq. (2)]

- [3, Fig. 7.2]

- [3, Appendix B]

If you create your own visual (table or graph) based on the data from a source, then your citation should refer to the source. You might include a note such as:

- Figure 4.2.4 data adapted from [3].

5. Do I need to keep citing the source every time I refer to it?

{12} Occasionally, you will use the same source for a larger section of your text from a few sentences to an entire paragraph. If you are discussing the ideas in a source at length (for example, in a summary or extended paraphrase), you can cite either the first time you mention the source or at the end of your summary or paraphrase. As long the following sentences clearly indicate that the ideas come from the same source—for example, you are using signal phrases, such as “the author further clarifies the problem by…”—you do not need to keep citing. Don’t be afraid to cite more often, however. And, if you stop using signal phrases, be sure to include a citation. If you introduce material from another source or add your own analysis between references to the source, you will also have to cite the source again when you refer to it. Always make sure your reader can identify those ideas that come from a source and those that originate with you. When you shift from one to the other, therefore, it is clearer to cite.

6. Should I mention every author if a source has more than one?

{13} When writing about a text, you will often find that you use the author’s last name (or surname) as a way of attributing claims to or of drawing on evidence from their work. Think of these attribution statements as signal phrases. If the source you are citing has one or two authors, use their names in your signal phrase:

- Brady [5] argues that ….

- Mehta and Barth’s study [6] demonstrates that ….

If the source has three or more authors, use the name of the lead author, followed by et al. (Latin for “and others”):

- Isaacson et al., in their study on fluid dynamics, found that ….

NOTE: in your Reference list at the end of your document, it is a courtesy to list the names of ALL the authors who contributed to the source (rather than using et al.). However, if there are 6 or more authors, it is acceptable to use et al. in your reference list as well.

7. Where do I find the bibliographic content that I need to create my references?

{14} The bibliographic information (the content that your reader needs to be able to locate your sources for themselves) varies from source to source. Fuller information on the preparation of the “References” list is provided below, and several sample entries for you to follow as models are available in Section 4.3. Typically, you will need:

- Authors’ names

- Article title (or book chapter/title or web site)

- Journal title (or book title and place of publication or web site production company)

- Date and publication information (volume and issue numbers for print journals; DOI for online journals; uniform resource locator (URL) for web sites)

Figure 4.2.1 provides the top section of the first page of a typical journal article. Everything you will need to create a reference list entry for this source can be found here (note: sometimes this information is provided at the top and bottom of the first page). The necessary information has been labelled for you.

8. How do I set up my References list?

{15} Different citation styles use various terms to introduce their list of references, for example, Bibliography or Works Cited. IEEE style uses the term References for the list of entries at the end of your document. The purpose of this list is to enable your reader to locate the sources of information or argumentation that you have drawn on or engaged with. This list will appear at the end of your document, though it usually comes before appendices or an index. Every source that you have referred to in your text should appear in the list, including sources that are cited as they appear in one of your sources. List all sources in the order you have cited them—that is, in numerical order (not in alphabetical order). Their order is determined by their appearance in your text (first source cited is [1], second source is [2], and so on).

{16} Each reference must provide correct and complete documentation, so readers can identify the kind of source and retrieve it. Section 4.3 includes illustrations of the most common source types and their formatting. It is important to use the correct conventions for each type of source, as readers familiar with such conventions will expect this from you. If you use conventions incorrectly (such as failing to italicize the appropriate item or to use quotation marks around article titles), you may confuse and/or mislead your readers.

Here are some general formatting guidelines for setting up your references list:

- Create a bold heading entitled REFERENCES that is aligned with the left margin.

- If you use other headings in your document, make this heading consistent with your first level headings.

- Align the square-bracketed numbered references ([1], [2], [3], [4], etc.) with the left margin.

- These should form a column of their own, with the text of the references indented so the numbers are easy for the reader to navigate (use the “hanging indent” function to format this, or use a table with invisible grid lines).

- Provide all authors’ names (unless there are 6 or more).

-

- Only use initials for first and middle names.

- Don’t invert the order.

- Separate names with commas, and include the word “and” before the last author.

-

- Capitalize only the first word (and the first word after a colon, as well as proper nouns) in titles of articles within journals, magazines and newspapers, chapters in books, conference papers, and reports.

-

- Only use ALL CAPS for acronyms.

-

- Capitalize the first letter of all main words in the titles of books, journals, magazines and newspapers.

{17} If you use citation software (such as Zotero, Endnote, or Mendeley) to generate a list of references, be sure to review the references it generates for any errors. These programs are not foolproof, and it is up to you to make sure your references conform to IEEE conventions. For example, sometimes the auto-generator will give a title in ALL CAPS or the author’s full first name. You will have to revise this. They usually do not give DOIs; you may have to add these. Some of you may use the in-text citation and References list generator in Microsoft Word. It remains your responsibility to check each entry in the list for accuracy and correctness after it is generated.

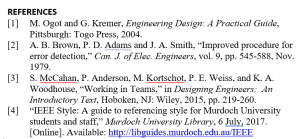

Sample References List

{18} The sample References list below illustrates IEEE formatting. Note the use of a hanging indent (the alley between the number and the entry) that increases the accessibility of the document by making it easy for the reader to follow the numbers. When your entry is two or more lines long, be sure that it doesn’t return under the numbers and into the alley. If you are manually setting up your list, you might find it helpful to use a table with two columns and as many rows as you need for your entries. Remember to turn off all table borders when you finish organizing the list.

9. How do I avoid plagiarism?

{19} Begin by taking careful notes. When you are working with your source material, take the time to identify in your notes where ideas or information originated. This will help you avoid accidentally moving material from your notes into your assignments without the proper documentation. Beyond taking careful notes, you need to become adept at using citations with quotations, summaries, and paraphrases from source material.

{20} Additional resources to help you avoid plagiarism are available on the “Citation + Plagiarism” page of the Niagara College Libraries web site. You’ll find tip sheets on avoiding plagiarism, short videos that explain what constitutes plagiarism, and information on your rights and responsibilities as students of Niagara College.

Media Attributions

- Chapter 4 Bibliographic Image

- Sample Ref List 4.2