3.6 Images

Image Basics

An image is a visual representation of something, There are two main types of images digital and analog. Digital images are created using a computer or camera. Analog images are film photographs and paintings. Resolution, bit-depth (colour depth) and colour management make up the core of a digital image.

Image resolution

A digital image is a structured matrix (or grid) of tiny squares known as pixels (picture elements). Each of these pixels has an assigned tonal value and when viewed in combination with surrounding pixels form the illusion of a continuous tone image.

Image resolution is simply a measurement of the density (or number) of pixels within the digital image. It describes the amount of detail encoded within a digital image. In the scanning world, resolution is a representation of the number of samples taken from the analogue original (photograph, document etc). In general, a greater number a samples (or higher resolution) should result in a more representative digital surrogate.

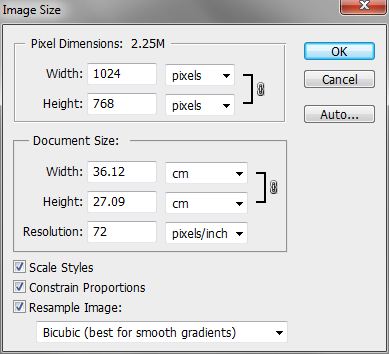

Resolution can be measured using two methods. In most software programs these are referred to as pixel dimensions and document size/pixels per inch.

Pixel dimensions (also known as pixel array) – makes reference to the number of pixels in the matrix arrangement (array) horizontally and vertically.

For example:

- 1024 x 768 pixels, or width=1024 and height=768

Document size/pixels per inch – resolution is most commonly expressed in pixels per inch (ppi) and measures the number of pixels per square inch.

For example:

- a 1 inch x 1 inch image @ 300ppi image = 300 x 300 pixels

Pixel per inch (ppi) is a variable measurement and is dependent on knowing the size of overall the image; without this scale (or magnification ratio) the measurement loses context.

[You might be familiar with the term dots per inch (dpi) and while the two terms are often interchangeable dpi refers to printed resolution whereas ppi refers to the pixels within the digital image file].

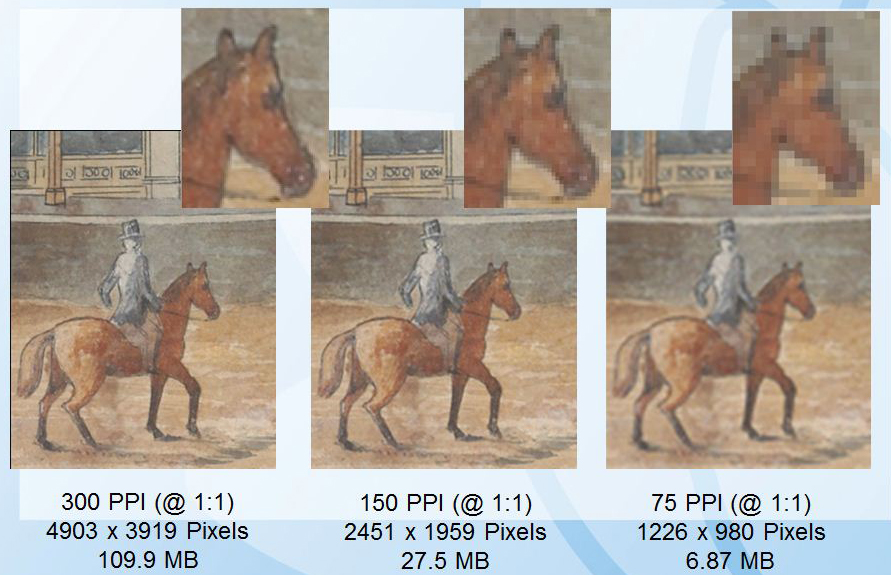

Example of image resolution

Here is an image from investigator records (University Hotel, Parramatta Road, Glebe 1890). Take note of the horse bottom right.

Digital ID: 9590_62784 Series: NRS 9590. Source: Image from Museums of History NSW – State Archives Collection, PDM.

Below is a close-up of the horse and shows three derivatives from the one master file. The higher the resolution, the greater the (uncompressed) file size – from 300ppi for printing down to 75ppi for web delivery.

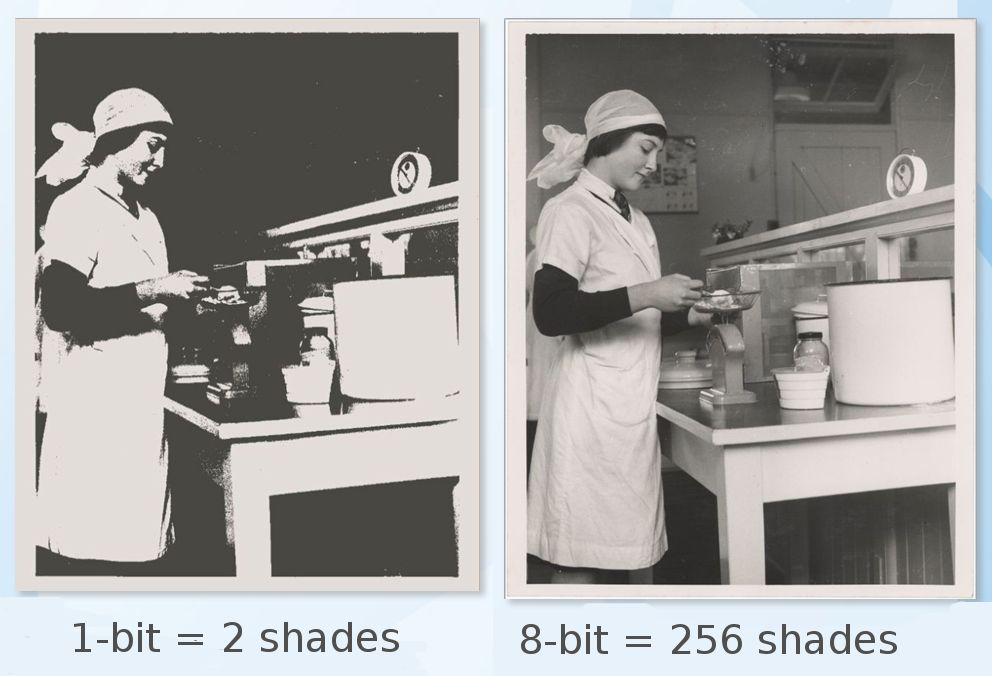

Bit depth (tonal or colour depth)

This is the measurement of the number of bits – or binary digits – devoted to storing the colour information about each pixel. The number of bits available determines the maximum possible range of colours and luminosity values (or grey shades) that can be represented within an image’s colour space or palette.

For instance, in a one bit image, each pixel is stored as a single bit (0 or 1) so there are only two digits available (black [0] or white [1]).

Colour management

Colour management outlines the colour capabilities of hardware devices – cameras, scanners, monitors and printers – by creating a translation (profile) that controls how the colour is displayed (or printed) by those devices.

Colour profiles ensure the quality of reproduced colour across many output devices. The minimum requirement for most projects should be an input profile outlining the colour space of the device that was used to digitise the document (most devices will default to sRGB).

Image File types

TIFF (TIF) – Tagged Image File Format

This is currently the preferred archival format for storage of images. It is the most common uncompressed image file type and retains all of the image information. It also offers lossless compression options (see below under File Compression). Most software programs use this format and it is available for both Macintosh and Windows.

JPG (JPEG) – Joint Photographic Experts Group

This format is highly compressed and removes “unnecessary” image information. Most software programs use this format and it is available for both Macintosh and Windows.

JPEG 2000

A compression standard enabling both lossless and lossy storage. The compression methods are different from the ones in standard JPEG and improve quality and compression ratios. However it requires more computational power (or to be more technical, grunt) to process.

| Format | Bit depth | Compression |

|---|---|---|

| TIFF (TIF) |

|

No Compression or Lossless (LWZ) |

| PNG |

|

Lossless (ZIP) |

| JPEG2000 (JP2) |

|

Lossless or Lossy |

| JPEG (JPG) |

|

Lossy |

| PSD |

|

No compression |

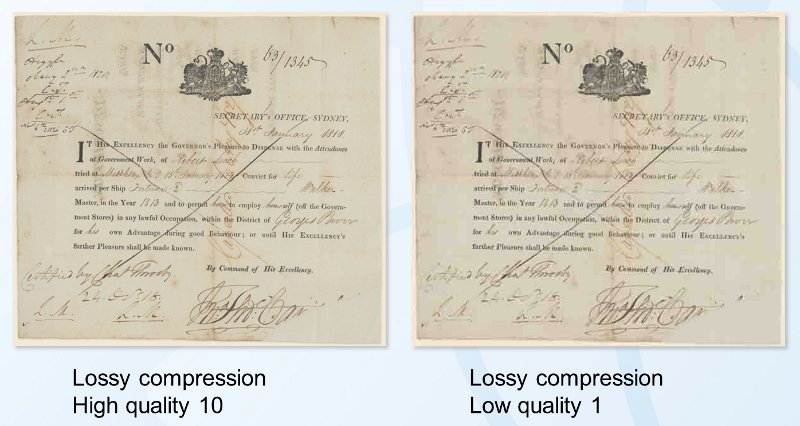

Image File compression

Compression shrinks the digital images for storage. There are two ways to compress:

- Lossless eg: TIFF – keeps all data by encoding the image files. It can reduce the file size by 40-60% information.

- Lossy eg: JPEG/JPG – this way of compression permanently removes “un-important data” (subtle colour/tonal information that is hard to distinguish with the human eye) aiming to strike a balance between acceptable loss of detail and bandwidth.

While lossless compression is preferable you can see in the image below that lossy compression doesn’t always show a loss of detail. It depends on the amount of compression that is applied which in turn depends on the image content and resolution.

The more compression applied the more visible the result. With lossy compression you can reduce an image from 1/10 to 1/20 of its original size without perceived loss.

Tip: Lossy Compression

Tip: Lossy Compression

Lossy compression is irreversible. Each time a jpeg file is saved – even after minor edits – it will lose quality.

Consider: Image Storage

Factors to consider for Image Storage

- Security – can the files be tampered with/can an unauthorised user gain access?

- Accessibility – are the files easy to retrieve by an authorised user? Is there a record of where items are stored? This could include sensible naming conventions for the digital files; organised folders/labels; keywords (metadata). Will they remain accessible long-term as storage systems change/or update?

- Media – will you store images on a hard-drive; USB stick/memory card? There’s no perfect medium – each has a limited lifespan.

- Back-ups – any of the above media could malfunction – have you made a back-up? Do you regularly update your back-up or check its functionality?

Attribution & References

Except where otherwise noted, this page is adapted from Digitising your collection – Part 3: Technical specifications, by Anthea Brown, NSW State Archives , CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 Australia License.