6.3 Video Editing

A Guide to Video Editing

Thanks to video sharing platforms, it is easier than ever to share videos over the internet. But how do you actually create a video?

If you’re making a viral 10 second video of your cat, then you can just pick up your phone, hit record, and then upload the video to the site of your choosing. However, you might want to cut together a few videos of your cat, and maybe put some explanations between the recorded footage about how your cat is technically able to make those impressive leaps.

This page explores approaches to working with digital video, starting by noting how many of the principles that apply to image and audio editing also apply here. We’ll also consider technical aspects like frame rate and resolution.

When making a video, you’ll want to plan out your approach. You’ll need to create or find different media, and then edit them together in a video editing tool before exporting your finished film to an appropriate filetype and generating subtitles.

Along with all of this, you can review Video Editing 101 video to go over the essentials and the slide decks for two topics, Introduction to filmmaking and Video editing skills, which will take you through the key considerations and tips for choosing and using the right tools.

Haven’t we seen this somewhere before?

Video may generally be thought of as a series of still images arranged together, one after the other, to give the illusion of movement. This is literally true of something like film where a string of photographic images are displayed in quick succession.

Digital video follows a similar model, but with raster images rather than celluloid. As such, most of the content on our section about images will be very relevant, albeit with the added dimension of time.

Since video is usually accompanied by audio too, and since a lot of the principles of digital audio extend to digital video, we’d also suggest taking a look at the audio page.

Frame rate

Frame rate is the speed at which one still image replaces another on the screen. The higher the frame rate, the smoother the illusory movement will appear.

This animated gif is made up of 15 still images (numbered 2-16) animating at 10 frames per second (10 fps or 10 Hz). Most cinema film animates at 24 fps (24 Hz): that’s sufficient to trick the eye for most humans, but you’ll often see higher frame rates than that.

Most digital video, like film, uses ‘progressive scan‘: a posh way of saying that one still image appears after another.

The most common framerate in digital recording is 30fps: 30p (where the ‘p’ stands for ‘progressive scan’). That’s because it’s aligned to what American television does (but more of that below). If you’re wanting to keep file sizes down, you should be able to get away with 25p, or even as low as 10p if you’re just recording a desktop application on a computer screen.

Tip: Framerates

The lower your framerate, the smaller your video file, but too low and your video will look jerky.

Interlace

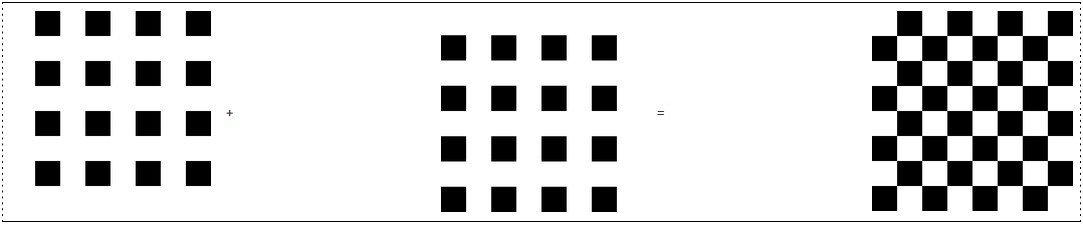

Unlike film, television (even digital television) typically uses a technique called ‘interlace‘: the odd-numbered rows of an image get sent first, and then the even-numbered rows (it’s a process derived from how cathode ray tubes scanned the image, back when television used cathode ray tubes, but that’s not important right now). Take this chess-board for instance:

If you see an ‘interlace’ setting, that’s what it does: It fillets your frames to half their size and interweaves them. This is great if your image is still but can be messy if things are moving about. If you ever work with television footage you’ll have to worry about something called deinterlacing which can prove to be a bit of a nightmare.

PAL television (the standard in the UK) uses 25fps (25Hz) but those 25 frames are interlaced meaning that you actually get an (albeit half-resolution) image 50 times per second: what’s referred to as 50i (where the “i” stands for “interlaced”). NTSC television (the American standard) works the same but at 30/50 fps: 60i. That’s why 30p is the predominant framerate for digital video.

Tip: Interlacing

Tip: Interlacing

Interlacing will reduce your file size by playing tricks with the vertical resolution, but that might create distortions if there’s a lot of movement in your video.

Groups of pictures

Not every frame of a digital video is necessarily a full image in its own right. The vast majority of digital video formats utilise something called Group of Pictures (GOP) – sometimes referred to as key frame distance. At its simplest, this works rather like JPEG compression, but in a third dimension: one frame of video (a “key frame” or “I-frame”) is an actual image, and the next few frames are rendered from that reference image using maths. The larger the GOP, the greater the risk of distortion artifacts. This is why flocks of birds tend to look rubbish on digital television, and why it takes a while for the picture to appear when you change channels (the television needs to wait for the next I-frame before it can show anything). A GOP that’s twice the framerate (in other words, one I-frame every two seconds) tends to be standard. So if your framerate is 30fps, you’d want a key frame every 60 frames. But that’s just a guide, and if the content of your frame doesn’t change that much, you can afford a much longer gap.

Tip: Key Frame Distance

The larger your GOP / key frame distance, the smaller your video file, but you’ll get more distortion the bigger you go, and you’ll also not be able to fast-forward as precisely.

Resolution and aspect ratio

As with digital images, size matters. But video has a very different history to that of the still image: a history wrapped up with that of television broadcasting. While a still image can be pretty much any size you like (within reason), there are certain standards to be aware of in video, and a whole new set of terminology for describing them.

Then there’s the fact that video resolution is usually expressed solely in terms of its height…

YouTube supports a range of standard sizes of video: 240p, 360p, 480p (equivalent to American standard definition TV), 720p, 1080p (equivalent to UK high definition TV), 1440p (also known as 2k), 2160p (4K ultra high definition – digital cinema standard), and 4320p (8k) — the ‘p’ refers to the ‘progressive scan’ method we mentioned above. In each case the value is the height of the picture in pixels.

Most monitors on campus (at the time of writing, at least) are 1920x1080px, which is also the most common monitor size more generally (again at the time of writing), so making videos at a higher resolution than 1080p is a waste of time unless you’re going for a theatrical release. But even 1080p will probably be excessive. A lot depends on the content of the video and what equipment your audience might be using to view it. After all, the higher the resolution the larger the file — some devices might struggle with high definition video content, and mobile devices are potentially going to be wasting their data on whatever you’re sharing.

That said, YouTube and Google let you choose a lower playback resolution than the original file, so the more prestigious your video, the higher you’ll want to set the resolution for the file you’re uploading. Still, the time’s you’ll need to go beyond 1080p will likely be few and far between.

So what about width? — aspect ratios

It’s complicated, and tied up with ratios… 4:3 (four units wide by three units tall) is the old television ratio but has now largely fallen out of use, having been replaced by 16:9 which is the standard widescreen TV ratio. 16:9 is also the most common ratio for a computer monitor, as well as being the ratio favoured by YouTube.

But those are just the two most common ratios, and the history of film is littered with others. The width of a 4:3 video should be 1.33…× its height, while for 16:9 it should be 1.77…× its height:

4:3

16:9

Standard definition (SD) television has a height of 576 pixels in Europe (PAL) or 480 pixels in America (NTSC). The number of pixels making up the width is not the same as the number of pixels you see on your screen: on Freeview (the UK’s main SD TV platform) it can be anything from 544px to 720px which then gets stretched to 768px for 4:3 and 1024px for 16:9 (widescreen).

High definition (HD) TV comes in two flavours: 720px height, or 1080px height (sometimes called FHD). Widths of 960 and 1440 have been common for 1080 broadcasts, though a full-width 1920px is increasingly seen as standard.

Then there’s Ultra High Definition (UHD), also known as 4K (confusingly a reference to its width!). 4K is 2160px high (twice that of HD). It’s 3840px wide (a natural 16:9), or 4096px wide in cinemas (hence the 4K). Videos of this size require a lot of processing so can be difficult to run on older devices. But a modern phone may well be able to record at that scale, so pay attention to your settings.

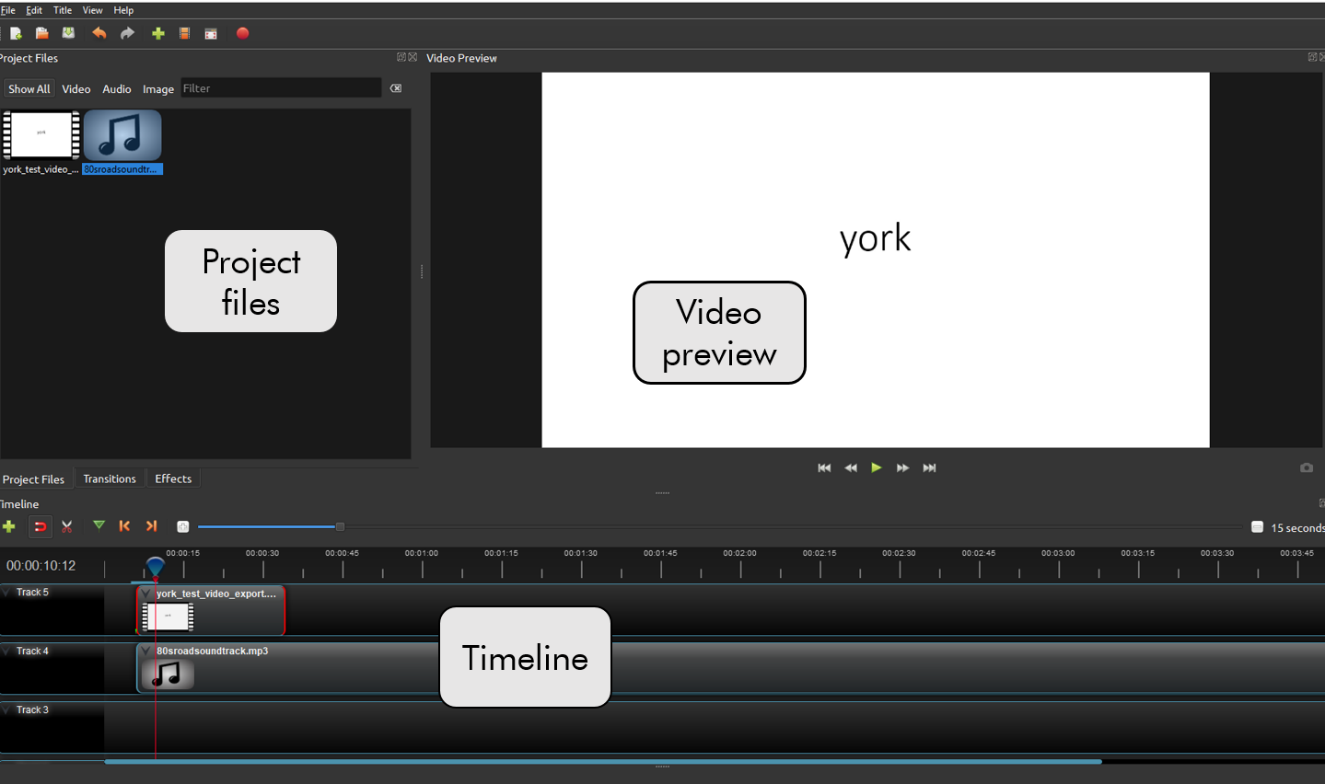

A typical video editor

Most video editing software follows the same basic layout conventions, though some programs will have more options and control panels than others. Here’s a typical example:

As well as the main features outlined below, there will be some options (either at the top or in a File menu) for modifying your project’s settings and for exporting your video into a final format. There also tends to be a range of mysterious buttons and options — hover over these to see a tooltip about what they do, or open a test project and try them out!

Most video editing tools will have built-in help from a menu, and may also have a walkthrough when you first open the application. Searching online for the name of the tool and what you’re trying to do can also be a good way to find help, particularly as there may be multiple methods of achieving the same result.

Tip: Confirming Settings

You may be asked to confirm the settings of your new project when you first open your video editor. You can generally go with the defaults, but you might want to modify certain settings if you’ve got a particular end in mind (for instance, if you’re going to need a higher resolution).

Let’s take a closer look at those typical main areas of the workspace:

Project files (assets)

To edit together a video, you need ‘assets‘ — the media files you will be using in your video. Your assets might just consist of a single video file you’ve recorded. But you could also import multiple video files, audio files or image files. It’s generally a good ideal to store all of your assets in a single folder and to give them sensible names.

If your assets are in common filetypes you should be able to import them into a video editing tool. There’s usually a section for assets somewhere to the left of the screen. Be sure to check that any images and video are of an appropriate resolution for the video you’re wanting to create (about the same as your frame size or bigger).

Once you’ve imported your assets you can drag them onto the timeline to add them to the video you’re creating.

Tip: Timeline

Anything you do on the timeline is only happening on the timeline — the underlying assets are unaffected. If you chop the end off of a video clip in the timeline, the end will still be there in the original asset.

Timeline

The timeline is the main part of your workspace: it’s where you compile and arrange the various parts of your video.

You can add an asset to your timeline by just dragging it into place. Often added items will ‘jump’ to the end of the timeline, but you can then reposition them to start at a specific timecode along your timeline. An item on a timeline is generally known as a clip. How fine you can position a clip will depend upon your framerate, so typically it will be to something like a 25th or a 30th of a second. Clips may ‘snap’ to other clips, but you can generally control this behaviour in the settings or perhaps avoid it by zooming further into your timeline.

Tracks

The timeline consists of multiple tracks which follow a layer principle whereby video (and image) items on tracks at the top of the timeline will cover up items on tracks lower down — you can have multiple tracks running at the same time, but only one of them can be visible on the screen.

You can add more than one item to the same track, but be careful of overlapping them in the same track — it might cause strange things to happen.

If you add an image to the timeline it will be converted into a video clip with default play length (sometimes ten seconds) which you can then modify (usually from a right-click context menu or by dragging the right-hand edge of the clip to the duration you want).

Audio may be separated from a video file and run as its own track. This can give you a bit more control over the sound of your video. Audio tracks can often be edited using the sort of techniques we looked at in the audio section, and a lot of the conventions of multitrack editing apply here too.

Video preview

The preview area is where you get to see how your video is actually looking at a given point along the timeline. There will usually be a traditional set of video playback controls here, but you can also use the playhead marker on the timeline to adjust the playback position.

Editing video

Having got your assets into your timeline, you’ll probably want to do something with them.

Let’s take a look at some basics:

Trimming and splitting

Just as with cutting and pasting in text, the language we use around video editing dates back to analogue days when film would literally be trimmed or clipped (with scissors) to a certain length (measured in feet, hence footage).

Just as with analogue film, the digital clips you add to your timeline might be too long, or they might need cutting into pieces and rearranging. Typically you’ll want to trim the start and end to remove unnecessary footage. To trim, you usually hover over one end of the clip until your cursor changes, then click and drag the cursor inwards to remove the start or end.

To split a clip, you typically need to use the playhead — the marker on the timeline that shows the current point that is being played. Move this to the point you want to split the clip (using the video preview to help you know where you’re at in the video), then there should be a scissors icon or ‘Split’ button you can use to split the clip at that point. You can then move around the separated clips (including onto separate tracks) or delete unnecessary parts.

Tip: Undo

Undo (CTRL + Z) will be your friend. You’ll probably have to use it quite a lot as you get used to the drag and drop interface and ways of trimming and splitting clips.

Transitions and effects

A transition is a visual effect that joins together two clips — for example a dissolve or a wipe.

A dissolve transition mixes between two clips.

You may want to add transitions between different clips, or between images and clips. You can even add special effects over a clip. Most video editors will have a selection of built-in transitions and effects, but you’ll probably want to use these sparingly unless you’re wanting something that looks like a cheap 1980s pop video — you don’t want to distract from your message and content.

To use a transition or effect, drag it onto the timeline over the relevant clip. You can then usually modify the properties of that effect to suit exactly what it is you want it to do.

Adding text

You could import an image or video with text on it, but most video editors also have built-in options for adding text. Text can be added over clips or over a blank background, for example for credits (and if you’ve used any third-party materials then you’ll probably want to provide some credits). Locate the text options in your tool then drag onto the timeline. You may edit the text in the video preview pane or when you insert it. You might need to use different tracks to get the text to appear exactly as you want, such as an overlay.

Be careful about how much text you add, and make sure you use an appropriately sized font so your audience can read it.

Saving, exporting, and sharing your video

Video editing requires a lot of your computer. Video files can be very big, so working with a lot of media at high resolutions will be a big drain on your computer’s memory and resources. Unless you have a particularly flashy computer, be prepared for video editing to take time.

Because video editing is so resource intensive, there’s a higher than average likelihood of your program crashing, so we’d suggest saving your project regularly. Whenever you’re happy with an edit you’ve made, hit the save button, and if you’ve made a significant change you might even want to save as a new project file, just so you can go back to the earlier state of things if you change your mind.

Exporting your video

Once you’ve edited your video together, it will need to be exported from the video editing tool into a single video file. There will be an Export (or Share) option, probably in the File menu or as its own button. You’ll be faced with a number of settings determining the kind of file you want to export, as well as its name and where you want to save it to.

Many video editors will give guidance around what each format is best for what use, and there may be some ready-made profiles you can use. For general use, MPEG-4 / H.264 / .mp4 are typically what you might want for a video you want to share or upload to a website. There will also be different quality options, and these will affect file size: higher quality videos can be very large files, so you might need to compromise quality in order to have a video that isn’t taking up obscene amounts of disc space, especially if you need to upload it to the internet. Take a look at our technical advice at the top of the page for a look at the various settings you’re likely to encounter.

Once you’ve chosen your format, there’ll be a button to select to start your export. It may take quite a while, depending on your video length and the encoding quality — the software will have to go through your entire video to create the file, so exporting might even take as long as if you were playing back your video from beginning to end; it may even take a lot longer!

Tip: Exporting

Exporting a video might require a lot of your computer, so you’re probably best leaving it alone for a while rather than trying to do something else on it at the same time. Go and get a cuppa and a good book.

Take a look at your exported video when it’s finished exporting. You might find that you need to try some different export options. I’ll put the kettle on, shall I?

Uploading and sharing a video

If you’re wanting to share your video on the internet in some way, you’re going to have to upload it. As we’ve said a few times now, videos are usually pretty big files, so uploading is going to take some time. It’s going to be a lot quicker on the campus network where we have much higher upload speeds than you’re likely to get on a home connection.

Given that uploading can be a slow process, this is another reason to ensure that you’re being as efficient as your use-case demands when exporting your video.

Tip: Uploading

Be prepared to have to step away from the computer again while your video uploads. If you’re uploading from home, you’re probably going to need another book!

Be sure to check the online copy of your video once it’s uploaded. It may take a while for whoever is hosting the video to process it before you can watch it. So be prepared to have to do even more waiting…

Videos uploaded to your Google Drive, or to a YouTube account will each have specific sharing permissions, that you can customize.

Subtitling

Subtitles are blocks of transcribed text that appear at the bottom of a video. Whether you’re deaf, struggling with an accent, watching the video in a distracting environment, or just don’t have the sound on, subtitles allow you to read the speech and sound of the video.

Containers and codecs

Video files contain both video and audio data, so a lot of video filetypes are quite relaxed about how that data is encoded so long as they’re wrapped up in a way that’s recognisable: they’re basically ‘containers‘ for different types of encoded video and audio which are then decoded by a coder-decoder (‘codec‘) program.

Encoding digital videos can therefore be a bit confusing: there are a lot of options, and a lot of codecs to choose from (not all of which are widely installed on people’s computers). So what video format should you choose?

H.264

By far the most common video format, H.264 (also known as Advanced Video Coding (AVC)) uses lossy compression that works in a similar sort of way to that of JPEGs and MP3s. It’s used in Blu-Ray discs, on most streaming platforms, and in an increasing amount of digital television broadcasting. It’s mostly used with the .mp4 container.

Other formats

There are a range of other formats and codecs to choose from, some of which have more adoption than others. Most formats can be played using VLC Media Player.

Sourcing video

Always bear in mind that published video is always subject to copyright law, so you can’t just use any sound you want.

Consider: Checking guidelines for videos

When creating videos for a particular purpose, you will often have guidelines or advice you will need to follow. Check this from the start, so you know if it affects your planning, filming, or editing. If you’re creating a video for an assessment, check how long it needs to be and how you need to submit it.

- What guidelines will you need to follow for video projects at school?

- What guidelines might be applicable if you’re creating a video for work purposes?

Attribution & References

Except where otherwise noted, this page was adapted from “Video” In A practical guide to media editing by University of York, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0. / Adaptations: removed links to University of York specific resources, cleaned up formatting, streamlined.