When a nurse administers medication, the ultimate goal is to provide client safety and prevent harm from medications. However, medical errors and adverse effects of medication therapy continue to be a significant problem in Canada. This section will discuss initiatives established by the Institute of Medicine (IOM), the World Health Organization (WHO), the Institute for Safe Medication Practices (ISMP) Canada, British Columbia Patient Safety and Quality Council (BCPSQC) and Health Quality Ontario (HQO).

Safety Culture

According to the Institute of Medicine, “The biggest challenge to moving toward a safer health system is changing the culture from one of blaming individuals for errors to one in which errors are treated not as personal failures, but as opportunities to improve the system and prevent harm.”[1] The British Columbia Patient Safety and Quality Council (BCPSQC) develops effective solutions for health care’s most critical safety and quality problems with a goal to ultimately achieving zero harm to clients. The Center has also been instrumental in creating a focus on a “Safety Culture” in health care organizations. A safety culture empowers staff to speak up about risks to clients and to report errors and near misses, all of which drive improvement in client care and reduce the incidence of client harm.

In addition to the BCPSQC, some health authorities in Canada also use electronic databases to collect and use evidence to support and sustain protocols that help identify drug misuse and see gaps (for example, the BC Patient Safety Learning System).

As a result of the focus on creating a safety culture, whenever a medication error or a “near-miss” occurs nurses should submit a safety event report according to their institution’s guidelines. The incident report triggers a root cause analysis to help identify not only what and how an event occurred, but also why it happened. When investigators are able to determine why an event or failure occurred, they can create workable corrective measures that prevent future errors from occurring.[2]

Based on results from incident report data, the Canadian Patient Safety Institute (CPSI), in partnership with the ISMP Canada, created a Medication Safety Action Plan to accelerate improvements in safe medication use in Canada. The action plan covers five major themes:[4]

- Reporting, learning and sharing – focusing on reporting medication safety events, but also actively and mindfully sharing results with relevant parties.

- Evidence-informed practices – focusing on developing and implementing evidence-informed guidelines for clinical practice to improve medication safety.

- Partnering with patients – shifting the professional culture to encourage open sharing of information between providers and clients.

- Education – ensuring clients have access to plain-language resources related to medication safety, and ensuring each member of the interdisciplinary team has a clear understanding of their roles with medication safety.

- Technology – integration of health care system technologies, while addressing privacy concerns.

The plan outlines clear goals and actions that health authorities can take in order to mitigate medication errors.

Reducing Medication Errors

The national focus on reducing medical errors has been in place for almost two decades. In Canada, researchers estimate that there are 70,000 preventable adverse events annually in hospitalized clients, and preventable mortalities in the range of 9,000 to 24,000. In response to this data, health organizations have aimed to break the cycle of inaction regarding medical errors by advocating a comprehensive approach to improving client safety. [5]

Despite the progress made in client safety over the last few years, medication errors remain extremely common, and the national health care system continues to implement initiatives to prevent errors. In 2015, ISMP Canada published a report titled Medication Error and Patient Safety: A Systems Approach, reporting that more than 7.5% (or 187,500) patients in Canadian hospitals were seriously harmed by their care. ISMP Canada emphasized systems-based actions that health care organizations, providers, and policy-makers/regulators could take to improve medication safety. These recommendations included actions such as automation or computerization of medication dispensing, standardization of order sets, electronic order sets, and improved policies/guidelines on medication administration. IOM and ISMP Canada also emphasize actions that individual clients can take to prevent medication errors, such as maintaining active medication lists and bringing their medications to appointments for review.[6][7]

On a global scale, multiple interventions to address the frequency and impact of medication errors have already been developed, yet their implementation has varied. In 2019, the World Health Organization (WHO) identified “Medication Without Harm” as a theme for the Global Patient Safety Challenge with the goal of reducing severe, avoidable medication-related harm by 50% over the next five years. As part of this challenge, WHO has prioritized three areas to protect clients from harm, while maximizing the benefit from medication:[8]

- Medication safety in high-risk situations

- Medication safety in polypharmacy

- Medication safety in transitions of care

A summary of these three areas and the strategies to reduce harm is provided below.

Medication Safety in High-Risk Situations

Medication safety in high-risk situations includes high-risk medications, provider-client relations, and systems factors.

High-risk (High-Alert) Medications

High-risk medications are drugs that bear a heightened risk of causing significant client harm when they are used in error. Although mistakes may or may not be more common with these medications, the consequences of an error are more devastating to clients. High-risk medication can be remembered using the mnemonic “A PINCH.” Figure 2.5 describes these medications included with the “A PINCH” mnemonic.

| High-Risk Medicine Group | Examples of Medicines |

|---|---|

| A: Anti-infective |

|

| P: Potassium and other electrolytes |

|

| I: Insulin |

|

| N: Narcotics & Other Sedatives |

|

| C: Chemotherapeutic Agents |

|

| H: Heparin & Anticoagulants |

|

Note: Based on research, the Institute of Safe Medication Practices (ISMP) has expanded this list. The list can be viewed at: ISMP List of High-Alert Medications in Acute Care Settings

Strategies for safe administration of high-alert medication include:

- Standardizing the ordering, storage, preparation, and administration of these products

- Improving access to information about these drugs

- Employing clinical decision support and automated alerts

- Using redundancies such as automated or independent double checks when necessary

Provider-Client Relations

In addition to high-risk medications, the second component of medication safety in high-risk situations includes provider and client factors. This component relates to either the health care professional providing care or the client being treated. Even the most dedicated health care professional is fallible and can make errors. The act of prescribing, dispensing, and administering medicine is complex and involves several health care professionals.

Clients also can present risk factors. For example, it is well-known that adverse drug events occur most often at the extremes of life (in the very young and in older people). In the older population, frail clients are likely to be receiving several medications concurrently, which adds to the risk of adverse drug events. In addition, the harm of some of these medication combinations may sometimes be synergistic and greater than the sum of the risks of harm to the individual agents. In neonates (particularly premature neonates), elimination routes through the kidney or liver may not be fully developed. The very young and the very old are also less likely to tolerate adverse drug reactions, either because their homeostatic mechanisms are not yet fully developed or because they may have deteriorated. Medication errors in children, where doses may have to be calculated in relation to body weight or age, are also a source of major concern. Additionally, certain medical conditions predispose clients to an increased risk of adverse drug reactions, particularly renal or hepatic dysfunction and cardiac failure. Interprofessional strategies to address these potential harms are based on a systems approach with a “prescribing partnership” between the client, the prescriber, the pharmacist, and the nurse.

Some other provider-related errors include: misinterpreting an abbreviation, misidentifying drugs due to look-alike labels and packages, mis-programming a pump due to a pump design flaw, or simply making a mental slip when distracted. We expand on a few of these, below. Other errors stem from systems problems and practice issues that are somewhat unique to environments where the interdisciplinary team is caring together for clients.

Error-Prone Abbreviations

Error-prone abbreviations are abbreviations, symbols, and dose designations that have been reported through the ISMP National Medication Errors Reporting Program as being frequently misinterpreted and involved in harmful medication errors. ISMP Canada’s Do Not Use Dangerous Abbreviations, Symbols, and Dose Designations should never be used when communicating medical information. Some examples of abbreviations that were commonly used that should now be avoided are qd, qod, qhs, BID, QID, D/C, subq, and APAP.[9]

Strategies to avoid mistakes related to error-prone abbreviations include not using these abbreviations in medical documentation. Furthermore, if a nurse receives a prescription containing an error-prone abbreviation, it should be clarified with the provider and the order rewritten without the abbreviation.

Do Not Crush List

The IMSP also maintains a list of oral dosage medication that should not be crushed, commonly referred to as the do not crush list. These medications are typically extended-release formulations.[10]

Strategies for preventing harm related to oral medication that should not be crushed include requesting an order for a liquid form or a different route if the client cannot safely swallow the pill form.

Look-Alike and Sound-Alike (LASA) Drugs

ISMP maintains a list of drug names containing look-alike and sound-alike name pairs such as captopril and carvedilol. These medications require special safeguards to reduce the risk of errors and minimize harm. For a full list of these medications, you can review the following resource ISMP Look Alike-Sound Alike List of Medications

Safeguards may include:

- Using both the brand and generic names on prescriptions and labels

- Including the purpose of the medication on prescriptions

- Changing the appearance of look-alike product names to draw attention to their dissimilarities

- Configuring computer selection screens to prevent look-alike names from appearing consecutively[11]

A nurse is preparing to administer insulin to a client. The nurse is aware that insulin is a medication on the ISMP list of high-alert medications.

What strategies should the nurse implement to ensure safe administration of this medication to the client?

Note: Answers to the activities can be found in the “Answer Key” sections at the end of the book.

Systems Factors

In addition to high-risk medications and provider-client relations, systems factors also contribute to medication safety in high-risk situations. Systems factors, also called the environment in hospitals, can contribute to error-provoking conditions for several reasons. The unit may be busy or understaffed, which can contribute to inadequate supervision or failure to remember to check important information. Interruptions during critical processes (e.g., administration of medicines) can also occur, which can have significant implications for client safety. Tiredness and the need to multitask when busy or flustered can also contribute to error, and can be compounded by poor electronic medical record design. Preparing and administering intravenous medications is also particularly error-prone. Strategies for reducing errors include checking at each step of the medication administration process; preventing interruptions; electronic provider order entry; and utilizing prescribing assessment tools.

Medication Safety in Polypharmacy

Polypharmacy is the concurrent use of multiple medications. Although there is no standard definition, polypharmacy is often defined as the routine use of five or more medications. This includes over-the-counter, prescription and/or traditional, and complementary medicines used by a client. As the population ages, more people are likely to suffer from multiple long-term illnesses and take multiple medications. It is therefore essential to take a person-centered approach to ensure that medications are appropriate for the individual, to gain the most benefits without harm, and to ensure that clients are integral to the decision-making process.

Appropriate polypharmacy is present when:

- all medicines are prescribed for the purpose of achieving specific therapeutic objectives with which the client has agreed;

- therapeutic objectives are actually being achieved or there is a reasonable chance they will be achieved in the future; or

- medication therapy has been optimized to minimize the risk of adverse drug reactions, and the client is motivated and able to take all medicines as intended.

Inappropriate polypharmacy is present when:

- one or more medicines are prescribed that are not or no longer needed, either because there is no evidence-based indication, the indication has expired or the dose is unnecessarily high;

- one or more medicines fail to achieve the therapeutic objectives they are intended to achieve;

- a medicine or the combination of several medicines put the client at a high risk of adverse drug reactions; or

- the client is not willing or able to take one or more medicines as intended.

When clients move across care settings, medication review is important to prevent harm caused by inappropriate polypharmacy. The WHO’s report, titled Medication Safety in Polypharmacy, includes the questions that should be addressed during a medication review with a multidisciplinary approach that includes the nurse.

Medication Safety in Transitions of Care

A third area of the WHO Medications Without Harm initiative relates to medication safety during transitions of care. View the interactive activity below to see how medications are reconciled during transitions of care from admission to discharge in a hospital setting.

Interactive Activity

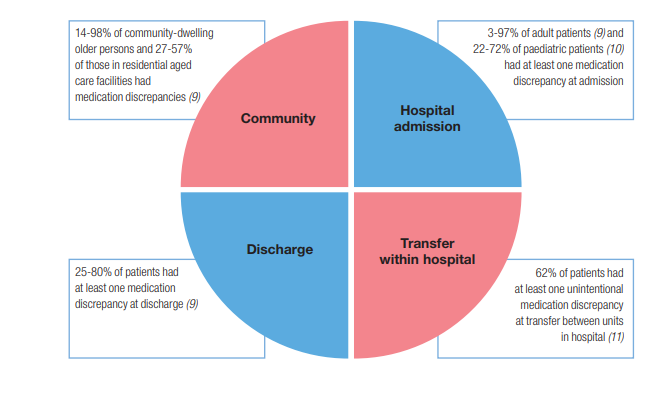

Medication errors can occur during these changes in settings. Figure 2.6[12] is an image from the WHO showing ranges of the percentage of errors that occur during common transitions of care.

Some suggested strategies for improving medication safety include:[13]

- Implement formal structured processes for medication reconciliation at all transition points of care. Steps of effective medication reconciliation include: building the best possible medication history by interviewing the client and verifying with at least one reliable information source; reconciling and updating the medication list; and communicating with the client and future health care providers about changes in their medications.

- Partner with clients, families, caregivers, and health care professionals to agree on treatment plans, ensuring clients are equipped to manage their medications safely and clients have an up-to-date medication list.

- Where necessary, prioritize clients at high risk of medication-related harm for enhanced support, such as post-discharge contact by a nurse.

A nurse is performing medication reconciliation for an elderly client admitted from home. The client does not have a medication list and cannot report the names, dosages, and frequencies of the medication taken at home.

What other sources can the nurse use to obtain medication information?

Note: Answers to the activities can be found in the “Answer Key” sections at the end of the book.

Supplementary Resources

Below are supplementary learning resources related to client safety and error prevention during medication administration.

Client example of medical errors.

Watch the Josie King Story about medical errors to gain perspective from a client who has experienced a medical error.

The Josie King Story and Medical Errors

Questions a nursing student may be asked about medications

As a student, when you prepare to administer medications to your clients during clinical care, your instructor will ask you questions to ensure safe medication administration.

See an example of the typical questions that a clinical instructor might ask. Enhancing Medication Safety in Clinical: A Video for Students and Nursing Faculty

BC Patient Safety and Quality Council

The BSPSQC was the basis for many references for this chapter; it also has several other resources that may be beneficial to your learning about client safety related to medication administration.

The Council provides system-wide leadership to efforts designed to improve the quality of health care in British Columbia. Through collaborative partnerships with health authorities, clients, and those working within the health care system, BCPSQC promotes and informs a provincially coordinated, client-centered approach to client safety and quality. The Council also provides numerous resources for health care professionals to help build competence in safety and quality. To view and register for upcoming learning programs related to client safety and quality, visit the BCPSQC website.

Image Description

Fig 2.6 description: This is is a circle divided into 4 quadrants to depict 4 areas where medication discrepancy can occur:

- Community: 14-98% of community-dwelling older person and 27-57% of those in residential aged care facilities had medication discrepancies.

- Hospital admission: 3-97% of adult patients and 22-72% of paediatric patients had at least one medication discrepancy at admission.

- Discharge: 25-80% of patients had at least one medication discrepancy at discharge.

- Transfer within hospital: 62% of patients had at least one unintentional medication discrepancy at transfer between units in hospital. [Return to Fig 2.6]

Attributions

- “Systems Factors” was adapted from Medication Safety in High Risk Situations by World Health Organization, which is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 licence.

- “Medication Safety in Polypharmacy” was adapted from Medication Safety in Polypharmacy by World Health Organization, which is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 licence.

- The Joint Commission. (2014, November). Facts about the safety culture project.https://www.centerfortransforminghealthcare.org/-/media/cth/documents/improvement-topics/cth_sc_fact_sheet.pdf ↵

- Patient Safety Network. (2019). Root cause analysis. https://psnet.ahrq.gov/primer/root-cause-analysis ↵

- Institute for Safe Medication Practices. (2007, November 29). Another heparin error: learning from mistakes so we don't repeat them. https://www.ismp.org/resources/another-heparin-error-learning-mistakes-so-we-dont-repeat-them ↵

- Patient Safety Institute. (2014). Medication Safety Action Plan. https://www.patientsafetyinstitute.ca/en/About/PatientSafetyForwardWith4/Documents/A%20Medication%20Safety%20Action%20Plan.pdf ↵

- Institute of Medicine. (2000). To Err Is Human: Building a Safer Health System. The National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/9728 footnote]Stelfox, H. T., Palmisani, S., Scurlock, C., Orav, E. J., and Bates, D. W. (2006). The "To Err is Human" report and the patient safety literature. Quality & Safety in Health Care, 15(3), 174–178. doi: 10.1136/qshc.2006.017947 ↵

- Institute of Medicine. (2007). Preventing medication errors. The National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/11623 ↵

- ISMP Canada (2015). Medication Error and Patient Safety: A Systems Approach. https://www.ismp-canada.org/download/presentations/SystemsApproach_ISMPCanada_18Nov2015.pdf ↵

- World Health Organization. (2019). Medication safety in key action areas. https://www.who.int/patientsafety/medication-safety/technical-reports/en ↵

- Institute for Safe Medication Practices. (2017, October 2). List of error-prone abbreviations. https://www.ismp.org/recommendations/error-prone-abbreviations-list ↵

- Institute for Safe Medication Practices. (2020, February 21). Oral dosage forms that should not be crushed.https://www.ismp.org/recommendations/do-not-crush ↵

- Institute for Safe Medication Practices. (2019, February 28). List of confused drug names. https://www.ismp.org/recommendations/confused-drug-names-list ↵

- This work is adapted from (2019) Medication Safety in Transition of Care by World Health Organization, https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/325453/WHO-UHC-SDS-2019.9-eng.pdf?ua=1 page 15, licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 ↵

- WHO. (2017). Medication Without Harm. https://www.who.int/initiatives/medication-without-harm ↵

- Healthcare.gov. (2011, May 25). Introducing the Partnerships for Patients with Sorrel King [Video]. YouTube. https://youtu.be/ak_5X66V5Ms ↵

The culture of a health care agency that empowers staff to speak up about risks to patients and to report errors and near misses, all of which drive improvement in patient care and reduce the incidence of patient harm.

An analysis after an error occurs to help identify not only what and how an event occurred, but also why it happened. When investigators are able to determine why an event or failure occurred, they can create workable corrective measures that prevent future errors from occurring.

The concurrent use of multiple medications.

Drugs that bear a heightened risk of causing significant patient harm when they are used in error.

Abbreviations, symbols, and dose designations that are frequently misinterpreted and involved in harmful medication errors.

A list of medications that should not be crushed, often due to a sustained-release formulation.

Medications that require special safeguards to reduce the risk of errors and minimize harm.

Present when one or more medicines are prescribed that are not or no longer needed.