Amanda Egert; Kimberly Lee; and Manu Gill

In this section, we will review common conditions and diseases related to the gastrointestinal system and elimination including hyperacidity, diarrhea, constipation, nausea, and vomiting.

Hyperacidity and Ulcers

Acid-related diseases can occur when there is an imbalance of secretions by the surface epithelium cells in the stomach.

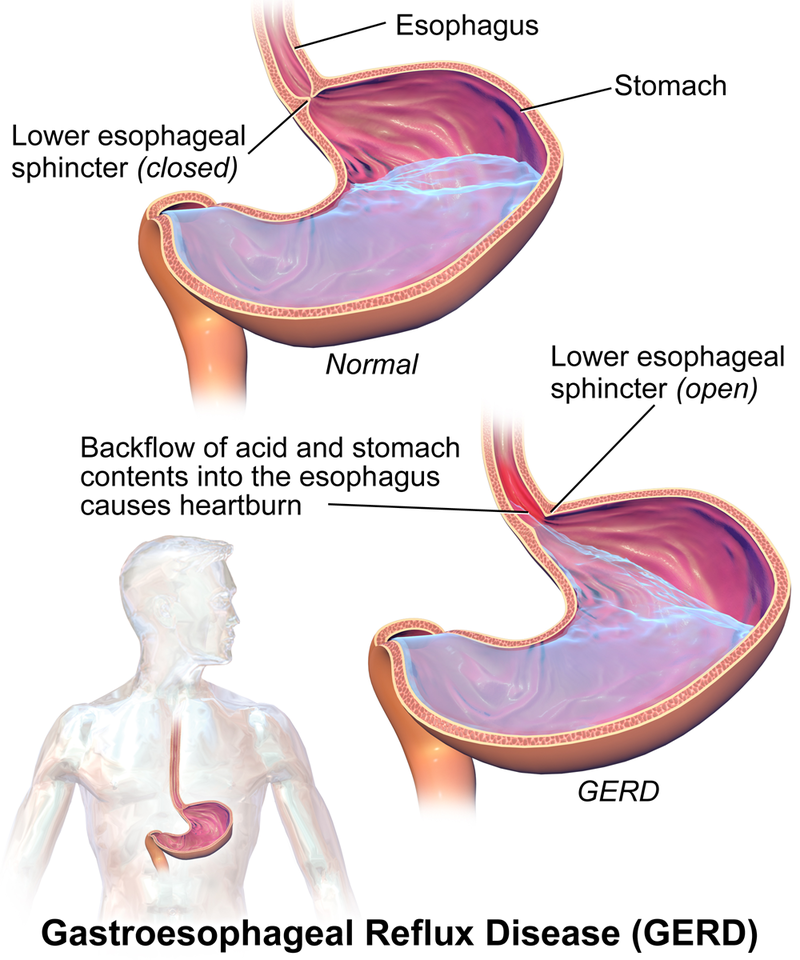

The most common mild to moderate hyperacidic condition is gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), often referred to by clients as heartburn, indigestion, or sour stomach. GERD is caused by excessive hydrochloric acid that tends to back up, or reflux, into the lower esophagus. See Figure 7.3a for an illustration of GERD.[1]

Peptic ulcer disease (PUD) occurs when gastric or duodenal ulcers are caused by the breakdown of GI mucosa by pepsin, in combination with the caustic effects of hydrochloric acid. PUD is the most harmful disease related to hyperacidity because it can result in bleeding ulcers, a life-threatening condition.

Stress-related mucosal damage is another common condition that can occur in hospitalized clients leading to PUD. Thus, many post-operative or critically ill clients receive medication to prevent the formation of a stress ulcer, which is also called stress ulcer prophylaxis.[2] See an image of a duodenal ulcer in Figure 7.3b.[3]

Here are some additional links to supplementary videos illustrating heartburn and gastric ulcers:

Diarrhea

Diarrhea itself is not a disease but is a sign and symptom of other conditions and disease processes in the body.

Diarrhea is defined as the passage of three or more loose or liquid stools per day (or more frequent passage than is normal for the individual). Frequent passing of formed stools is not considered diarrhea. Diarrhea has multiple causes such as bacteria from contaminated food or water; viruses such as influenza, norovirus, or rotavirus; parasites found in contaminated food or water; medicines such as antibiotics, cancer drugs, and antacids that contain magnesium; food intolerances and sensitivities; and diseases that affect the colon, such as Crohn’s disease or irritable bowel syndrome.[6]

The most severe threat posed by diarrhea is dehydration caused by the loss of water and electrolytes. Diarrheal disease is a leading cause of child mortality and morbidity throughout the world due to dehydration; frail elderly are also at risk. When severe diarrhea occurs, assessment for dehydration and electrolyte imbalances receive top priority and rehydration with oral rehydration solutions or IV fluids may be required.[7]

Constipation

Constipation is defined as “three or fewer bowel movements in a week; stools that are hard, dry or lumpy; stools that are difficult or painful to pass; or the feeling that not all stool has passed.”[8] If defecation is delayed for an extended time, additional water is absorbed, thus making the feces firmer and potentially leading to constipation. There are several causes of constipation, such as lack of proper fluids or fiber in the diet, lack of ambulation, various disease processes, recovery from surgical anesthesia and opiates, and side effects of many medications. A list of these potential causes can be found in Table 7.3a.[9] Because there are several potential causes of constipation, treatment should always be individualized to the client. Many times, constipation can be treated with simple changes in diet, exercise, or routine. However, when medications are also needed to resolve constipation, there are several categories of laxative medications that work in different ways. Classes of laxative medications are described below.

| Cause | Examples |

|---|---|

| Medications |

|

| Health and Nutrition Problems |

|

| Daily Routine Changes |

|

Nausea and Vomiting

Similar to diarrhea and constipation, nausea and vomiting are common conditions that are most often signs and symptoms of other conditions or side effects of medication.

Nausea is the unpleasant sensation of having the urge to vomit, and vomiting (emesis) is the forceful expulsion of gastric contents.[10]

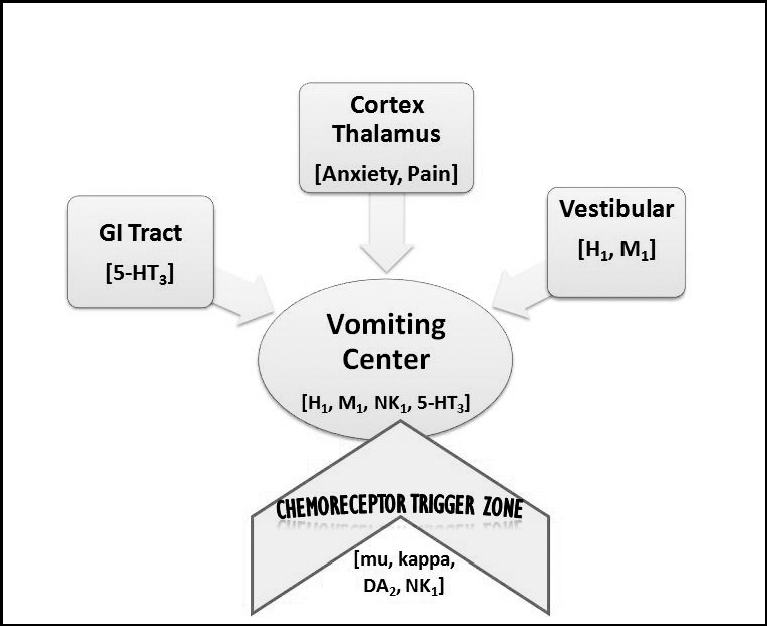

The vomiting center can be activated directly by irritants or indirectly following input from four principal areas: gastrointestinal tract, cerebral cortex and thalamus, vestibular region, and chemoreceptor trigger zone (CRTZ). See Figure 7.3c for an illustration of the pathophysiology of nausea and vomiting.[11]

An important part of the emesis circuit is the chemoreceptor trigger zone (CTZ), located in the area postrema in the brain. The CTZ is not restricted by the blood–brain barrier, which allows it to respond directly to toxins in the bloodstream such as anesthesia and opioids. The CTZ also receives stimuli from several other locations in the body including the vestibular center; visceral organs such as the GI tract, kidneys, and liver; the thalamus; and the cerebral cortex.

The vestibular center and cerebral cortex can stimulate the vomiting center directly or indirectly through the CTZ. The vestibular system is located within the inner ear and gives a sense of balance and spatial orientation for the purpose of coordinating movement with balance. The feeling of nausea associated with motion sickness often arises from stimuli from the vestibular center. The gastrointestinal tract sends stimuli to the CTZ via cranial nerves IX and X related to obstruction, distension, inflammation, and infection. The cerebral cortex and other parts of the brain can also stimulate a sense of nausea related to odors, tastes, and images and send these stimuli to the CTZ. The CTZ forwards these signals to the vomiting center in the brain. Pain can also directly stimulate the vomiting center.

The vomiting center (VC) is located in the medulla in the brain. In response to these stimuli, the vomiting center initiates vomiting by inhibiting peristalsis and producing retro-peristaltic contractions beginning in the small bowel and ascending into the stomach. It also produces simultaneous contractions in the abdominal muscles and diaphragm that generate high pressures to propel the stomach contents upwards. Additionally, autonomic stimulation of the heart, airways, salivary glands, and skin cause other symptoms associated with vomiting such as salivation, palor, sweating, and tachycardia. Several neurotransmitters are involved in the nausea and vomiting process, and antiemetic medications are targeted to specific neuroreceptors.[12]

There are many potential causes of nausea and vomiting, such as:

- Morning sickness during pregnancy

- Gastroenteritis and other infections

- Migraines

- Motion sickness

- Food poisoning

- Side effects of medicines, including those for cancer chemotherapy

- GERD and ulcers

- Intestinal obstruction

- Poisoning or exposure to a toxic substance

- Diseases of other organs (cardiac, renal, or liver)

A health care provider should be contacted immediately if the following conditions occur:

- Vomiting for longer than 24 hours

- Blood in the vomit (also called hematemesis)

- Severe abdominal pain

- Severe headache and stiff neck

- Signs of dehydration, such as dry mouth, infrequent urination, or dark urine

Image Descriptions

Figure 7.3a image description: Illustration of GERD.

The stomach is located in the upper left quadrant of the abdomen and the esophagus comes down from the throat to the stomach.

When it is normal, the lower oesophageal sphincter, which is between the esophagus and stomach, is closed. Stomach acid and stomach contents sit in the stomach.

When a person has GERD, the lower esophageal sphincter is open. This allows a back flow of acid and stomach contents into the esophagus, which causes heartburn. [Return to figure 7.3a]

Figure 7.3c image description: The pathophysiology of nausea and vomiting.

The Vomiting Center sits in the centre. The receptors illustrated in the vomiting center are:

- H1 histamine

- M1 acetylcholine

- NK1 (neurokinin), and 5-HT3 serotonin.

Four principal areas can activate the vomiting center:

- GI Tract (5-HT3 serotonin)

- Cortex Thalamus (Anxiety, Pain)

- Vestibular (H1 histamine, M1 acetylcholine)

- Chemoreceptor trigger zone (mu/kappa opioids, DA2 dopamine, and NK1 (neurokinin)) [Return to figure 7.3c]

- "GERD.png" by BruceBlaus is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0 ↵

- Lilley, L., Collins, S., & Snyder, J. (2014). Pharmacology and the Nursing Process. pp. 782-862. Elsevier. ↵

- ""Duodenal ulcer01.jpg" by melvil is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0 ↵

- MedlinePlus. Bethesda (MD): National Library of Medicine (US); [updated 2019 October 23]. Heartburn; [updated 2019 October 2; cited 2019 October 27] https://medlineplus.gov/ency/anatomyvideos/000068.htm ↵

- Blausen Medical. (2015, November 17). Gastric Ulcers [Video].https://blausen.com/en/video/gastric-ulcers/# ↵

- A.D.A.M. Medical Encyclopedia [Internet]. Atlanta (GA): A.D.A.M., Inc.; ©2019. Heartburn; [reviewed 2019 May 10; cited 2019 October 27]. https://medlineplus.gov/ency/anatomyvideos/000068.htm ↵

- World Health Organization. (2017, May 2). Diarrhoeal disease.https://www.who.int/en/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/diarrhoeal-disease. ↵

- National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, National Institute of Health. (2018). Symptoms and causes of constipation.https://www.niddk.nih.gov/health-information/digestive-diseases/constipation/symptoms-causes ↵

- National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, National Institute of Health. (2018). Symptoms and causes of constipation.https://www.niddk.nih.gov/health-information/digestive-diseases/constipation/symptoms-causes ↵

- Bashashati, M. & McCallum, R. (2014). Neurochemical mechanisms and pharmacologic strategies in managing nausea and vomiting related to cyclic vomiting syndrome and other gastrointestinal disorders. European Journal of Pharmacology, 772, p 79. ↵

- Becker D. E. (2010). Nausea, vomiting, and hiccups: a review of mechanisms and treatment. Anesthesia progress, 57(4), 150–157. doi:10.2344/0003-3006-57.4.150 ↵

- Becker D. E. (2010). Nausea, vomiting, and hiccups: a review of mechanisms and treatment. Anesthesia progress, 57(4), 150–157. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3006663/ ↵

Caused by excessive hydrochloric acid that tends to back up, or reflux, into the lower esophagus.

Occurs when gastric or duodenal ulcers are caused by the breakdown of GI mucosa by pepsin in combination with the caustic effects of hydrochloric acid.

A common condition in hospitalized patients that can lead to PUD.

Medication to prevent the formation of stress ulcers.

The passage of three or more loose or liquid stools per day (or more frequent passage than is normal for the individual).

Three or fewer bowel movements in a week; stools that are hard, dry or lumpy; stools that are difficult or painful to pass; or the feeling that not all stool has passed.

Area in the brain that responds directly to toxins in the bloodstream and stimulates the vomiting center. The CTZ receives stimuli from several other locations in the body.

A structure in the medulla oblongata in the brainstem that controls vomiting. Its location in the brain also allows it to play a vital role in the control of autonomic functions by the central nervous system.

An area located within the inner ear that gives a sense of balance and spatial orientation for the purpose of coordinating movement with balance.

An area in the brain that initiates vomiting by inhibiting peristalsis and producing retro peristaltic contractions beginning in the small bowel and ascending into the stomach. It also produces simultaneous contractions in the abdominal muscles and diaphragm that generate high pressures to propel the stomach contents upwards.

Infection of the intestines.

Blood in the vomit.