Nursing Fundamentals

Nursing Fundamentals

Nursing Fundamentals

Nursing Fundamentals

Nursing Fundamentals by Chippewa Valley Technical College is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted.

Introduction

1

This Nursing Fundamentals textbook is an open educational resource with CC-BY licensing developed for entry-level nursing students. Content is based on the Wisconsin Technical College System (WTCS) statewide nursing curriculum for the Nursing Fundamentals course (543-101), the 2019 NCLEX-RN Test Plan,NCSBN. (n.d.). 2019 NCLEX-RN test plan. https://www.ncsbn.org/2019_RN_TestPlan-English.htm the 2020 NCLEX-PN Test Plan,NCSBN. (2019). NCLEX-PN Examination: Test plan for the national council licensure examination for practical nurses. https://www.ncsbn.org/2020_NCLEXPN_TestPlan-English.pdf and the Wisconsin Nurse Practice Act.Wisconsin State Legislature. (2018). Chapter 6: Standards of practice for registered nurses and licensed practical nurses. Board of Nursing. https://docs.legis.wisconsin.gov/statutes/statutes/441

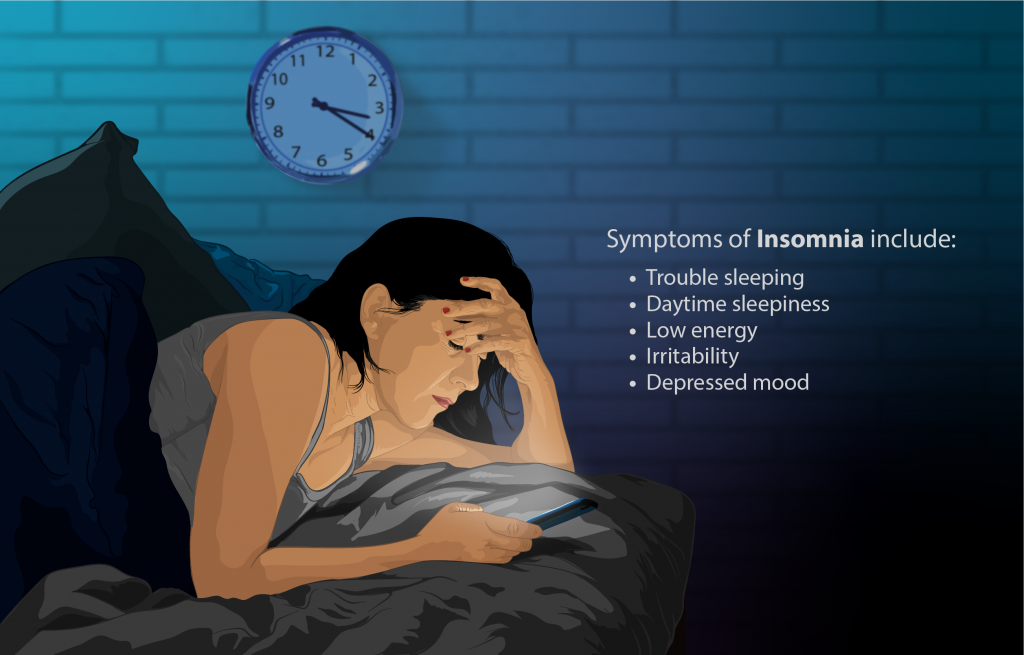

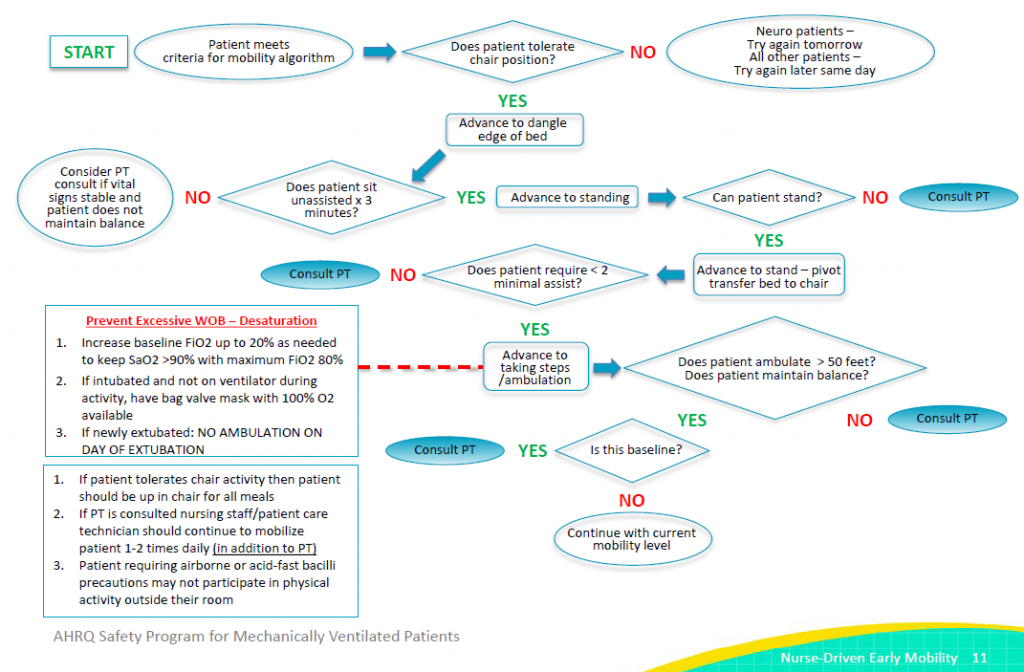

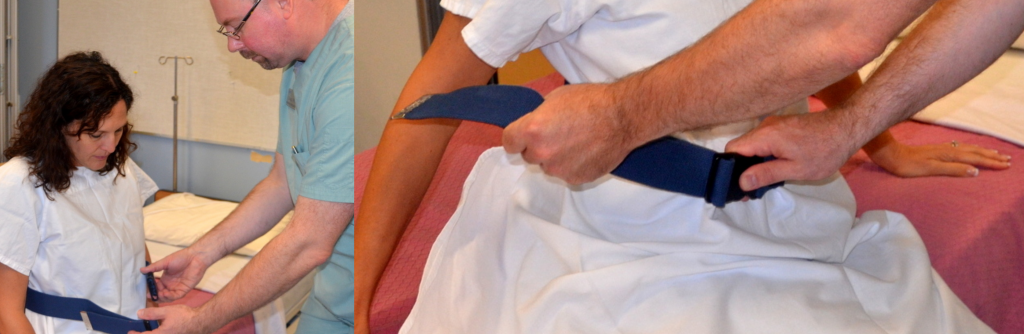

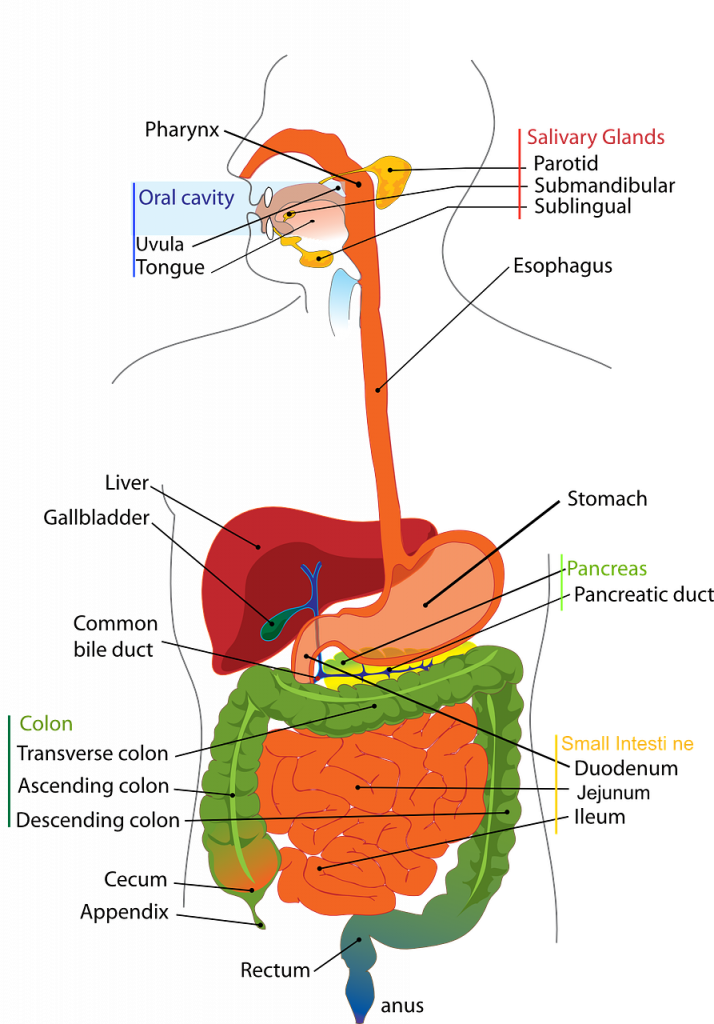

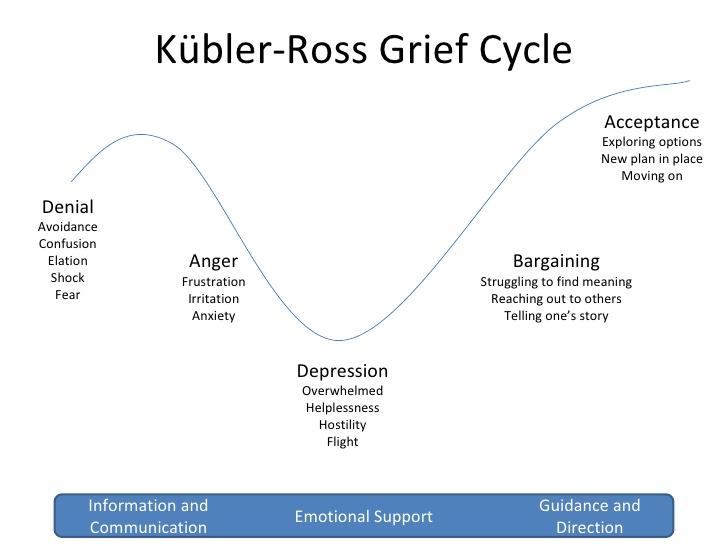

This book introduces the entry-level nursing student to the scope of nursing practice, various communication techniques, and caring for diverse patients. The nursing process is used as a framework for providing patient care based on the following nursing concepts: safety, oxygenation, comfort, spiritual well-being, grief and loss, sleep and rest, mobility, nutrition, fluid and electrolyte imbalance, and elimination. Care for patients with integumentary disorders and cognitive or sensory impairments is also discussed. Learning activities have been incorporated into each chapter to encourage students to use critical thinking while applying content to patient care situations.

The Open Resources for Nursing (Open RN) project is supported by a $2.5 million grant from the Department of Education. This book is available for free online and can also be downloaded in multiple formats for offline use. The online version is required for interaction with adaptive learning activities included in each chapter. Affordable print versions may also be purchased from XanEdu in college bookstores and on Amazon.

The following video provides a quick overview of how to navigate the online version.

Preface

2

This Nursing Fundamentals textbook is an open educational resource with a CC-BY 4.0 license developed for entry-level prelicensure nursing students. Content is based on the Wisconsin Technical College System (WTCS) statewide nursing curriculum for the Nursing Fundamentals course (543-101), the 2019 NCLEX-RN Test Plan,NCSBN. (n.d.). 2019 NCLEX-RN test plan.https://www.ncsbn.org/2019_RN_TestPlan-English.htm the 2020 NCLEX-PN Test Plan,NCSBN. (2019). NCLEX-PN Examination: Test plan for the national council licensure examination for practical nurses.https://www.ncsbn.org/2020_NCLEXPN_TestPlan-English.pdf and the Wisconsin Nurse Practice Act.Wisconsin State Legislature. (2018). Chapter 6: Standards of practice for registered nurses and licensed practical nurses. Board of Nursing. https://docs.legis.wisconsin.gov/statutes/statutes/441

The project is supported by a $2.5 million Open Resources for Nursing (Open RN) grant from the Department of Education to create five free, open source nursing textbooks. However, this content does not necessarily represent the policy of the Department of Education, and you should not assume endorsement by the federal government.

More information about the Open RN grant can be found at cvtc.edu/OpenRN. The first textbook of the Open RN textbook series, Nursing Pharmacology, received an OE Award for Excellence from OE Global. For more information, visit the 2020 OE Awards for Excellence site.

Usage Survey and Feedback

We would love to hear if you have integrated some or all of this resource into your course. Please use this short survey to report student usage information every semester that is reported to the Department of Education. Please use this survey to provide constructive feedback or report any errors.

About this Book

Editors

- Kimberly Ernstmeyer, MSN, RN, CNE, CHSE, APNP-BC

- Dr. Elizabeth Christman, DNP, RN, CNE

Graphics Editor

- Nic Ashman, MLIS, Librarian, Chippewa Valley Technical College

Developing Authors

Developing authors remixed existing open educational resources and developed new content based on evidence-based sources:

- Leeann Anthon, MSN, RN, CNE, Madison Area Technical College

- Dr. Lisa Blohm, PhD, RN, Northeast Wisconsin Technical College

- Barbara Brown, MSN, RN, Moraine Park Technical College

- Dr. Elizabeth Christman, DNP, RN, CNE, Chippewa Valley Technical College/Southern New Hampshire University

- Tami Davis, MSN, RN, Chippewa Valley Technical College

- Kim Ernstmeyer, MSN, RN, CNE, CHSE, APNP-BC, Chippewa Valley Technical College

- Dr. Allison Nicol, PhD, RN, CNE, Milwaukee Area Technical College

- Dr. Valerie Palarski, EdD, MSN/ED, RN, Northcentral Technical College

- Lynda Rastall, MSN, RN, CNE, Northeast Wisconsin Technical College

- Julie Sigler, MSN, RN, Chippewa Valley Technical College

Contributors

Contributors assisted in the creation of this textbook:

- Jane Flesher, MST, Proofreader, Chippewa Valley Technical College

- Deanna Hoyord, Paramedic (retired), Human Patient Simulation Technician and Photographer, Chippewa Valley Technical College

- Theresa Meinen, MS, RRT, CHSE, Director of Clinical Education – Respiratory Therapy Program, Chippewa Valley Technical College

- Vince Mussehl, MLIS, Open RN Lead Librarian, Chippewa Valley Technical College

- Joshua Myers, Web Developer, Chippewa Valley Technical College

- Meredith Pomietlo, Retail Design and Marketing Student, UW-Stout

- Lauren Richards, Graphics Designer, Chippewa Valley Technical College

- Celee Schuch, Nursing Student, St. Catherine University

- Christina Sima, MSN, RN, Gateway Community College

- Dominic Slauson, Technology Professional Developer, Chippewa Valley Technical College

- Dr. Jamie Zwicky, EdD, MSN, RN, Moraine Park Technical College

Advisory Committee

The Open RN Advisory Committee consists of industry members and nursing deans and provides input for the Open RN textbooks and virtual reality scenarios:

- Jenny Bauer, MSN, RN, NPD-BC, Mayo Clinic Health System Northwest Wisconsin, Eau Claire, WI

- Gina Bloczynski, MSN, RN, Dean of Nursing, Chippewa Valley Technical College

- Angela Branum, Western Wisconsin Health

- Lisa Cannestra, Eastern Wisconsin Healthcare Alliance

- Travis Christman, MSN, RN, Clinical Director, HSHS Sacred Heart and St. Joseph’s Hospitals

- Sheri Johnson, UW Population Health Institute

- Dr. Vicki Hulback, DNP, RN, Dean of Nursing, Gateway Technical College

- Jenna Julson, MSN, RN, NPD-BC, Nursing Education Specialist, Mayo Clinic Health System Northwest Wisconsin, Eau Claire, WI

- Brian Krogh, MSN, RN, Associate Dean – Health Sciences, Northeast Wisconsin Technical College

- Hugh Leasum, MBA, MSN, RN, Nurse Manager Cardiology/ICU, Marshfield Clinic Health System, Eau Claire, WI

- Pam Maxwell, SSM Health

- Mari Kay-Nobozny, NW Wisconsin Workforce Development Board

- Dr. Amy Olson, DNP, RN, Nursing Education Specialist, Mayo Clinic Health System Northwest Wisconsin, Eau Claire, WI

- Rorey Pritchard, EdS, MEd, MSN, RN-BC, CNOR(E), CNE, Senior RN Clinical Educator, Allevant Solutions, LLC

- Kelly Shafaie, MSN, RN, Associate Dean of Nursing, Moraine Park Technical College

- Dr. Ernise Watson, PhD, RN, Associate Dean of Nursing, Madison Area Technical College

- Sherry Willems, HSHS St. Vincent Hospital

Reviewers

- Emily Adams, MSN, RN, CNE, Arizona Western College

- Ava Alden, Nursing Student, St. Catherine University

- Dr. Caryn Aleo, PhD, RN, CCRN, CEN, CNEcl, NPD-BC, Pasco-Hernando State College

- Dr. Kimberly A. Amos, PhD, MS(N), RN, CNE, Isothermal Community College

- Sara Annunziato, MSN, RN, Rockland Community College

- Megan Baldwin, MSN, RN, CNOR, MercyOne Medical Center, Des Moines, Iowa

- Jenny M. Bauer, MSN, RN, NPD-BC, Mayo Clinic Health System, Northwest Wisconsin

- Lisa Bechard, MSN, RN, Mid-State Technical College

- Ginger Becker, Nursing Student, Portland Community College

- Jolan Berg, MSN, RN, Madison Area Technical College

- Nancy Bonard, MSN, RN-BC, Saint Joseph’s College of Maine

- Valerie J. Bugosh, MSN, RN, CNE, Harrisburg Area Community College

- Dr. Sara I. Cano, PhD, RN, College of Southern Maryland

- Katherine Cart, MSN, MA, RN, Blinn College

- Travis Christman, MSN, RN, HSHS Sacred Heart and St. Joseph’s Hospitals

- Pasang Comfort, Nursing Student, Portland Community College

- Lenore Cortez, MSN, RN-C, Angelo State University

- Dr. Catina Davis, DNP, RN, Tidewater Community College

- Dr. Gerrin Davis, DNP, MA, CRNP, FNP-C, Community College of Baltimore County-Catonsville

- Dr. Andrea Dobogai, DNP, RN, Moraine Park Technical College

- Stacy Svoma Doering, MAEd, RDMS, RVT, Chippewa Valley Technical College

- Jessica Dwork, MSN-ED, RN, Maricopa Community College

- Dr. Maria Motilla Fabro, DNP, APRN-Rx, FNP-BC, Kaua’i Community College

- Dr. Rachael Farrell, EdD, RN, CNE, Howard Community College

- Kathleen Fraley, MSN, RN, St. Clair County Community College

- Kailey Funk, MSN, RN, Madison College

- Kristin Gadzinski, MSN, RN, Lakeshore Technical College

- Amy Gatton, MSN, CNE, Nicolet Area Technical College

- Carla Genovese, MSN, RN-BC, CCRN, Flathead Valley Community College

- Kerry L. Hamm, MSN, RN, Lakeland University

- Melissa Hauge, MSN, RN-BC, Madison College

- Sharon Rhodes Hawkins, MPA, MSN/ed, RN, Sinclair Community College

- Camille Hernandez, MSN, RN, ACNP/FNP-BC, Hawai’i Community College

- Kristine Sioson Holden, MSN, RN, Prince George’s Community College

- Lexa Hosier, Nursing Student, St. Catherine University

- Katherine Howard, MS, RN-BC, CNE, Middlesex County College

- Jenna Julson, MSN, RN, NPD-BC, Mayo Clinic Health System, Northwest Wisconsin

- Lindsay A Kuhlman, BSN, RN, HSHS Sacred Heart Hospital

- Erin Kupkovits, MSN, RN, Madison Area Technical College

- Julie Lepianka, MSN, RN, CNE, Moraine Park Technical College

- Tamella P. Livengood, MSN, FNP-C, Northwestern Michigan College

- Kathy L. Loppnow, MSN, RN, WTCS Health Education Director

- Dawn M. Lyon, MSN, RN, St. Clair County Community College

- Dr. Lydia A. Massias, EdD, MS, RN, Pasco- Hernando State College

- Dr. Jamie Murphy, PhD, RN, State University of New York, Delhi

- Angela Ngo-Bigge, MSN, RN, FNP-C, Grossmont College

- Dr. Tennille O’Connor, DNP, RN, CNE, Pasco- Hernando State College

- Dr. Lilleth D. Okossi, DNP, RN, ACNS-BC, CCRN, Bergen Community College

- Dr. Amy Olson, DNP, RN, Mayo Clinic Health System, Northwest Wisconsin

- Jane Palmieri, MSN, RN, Portland Community College

- Laurie E. Paugel, MSN, RN, Nicolet College

- Dr. Grace Paul, DNP, RN, CNE, Glendale Community College

- Krista Polomis, MSN, RN, Nicolet College

- Mary Pomietlo, MSN, RN, CNE, University of Wisconsin – Eau Claire

- Cassandra Porter, MSN, RN, Lake Land College

- Rorey Pritchard, EdS, MSN, MEd, RN-BC, NPD, CNE, CNOR(E), Allevant Solutions, LLC

- Dr. Regina Prusinski, DNP, APRN, CPNP-AC, BC FNP, Otterbein University

- Jen Renstrom-Dallman, MSN, RN, Chippewa Valley Technical College

- Sharon Rhodes Hawkins, MPA, MSN, RN, Sinclair Community College

- Dr. Debbie Rickeard, DNP, BScN, BA, RN, CNE, CCRN, University of Windsor, Canada

- Dr. Julia E. Robinson, DNP, MSN, APRN, FNP-C, GCNS-BC, Palomar Community College

- Ann K. Rosemeyer, MSN, RN, Chippewa Valley Technical College

- Callie Schlegel, Nursing Student, St. Catherine University

- Celee Schuch, Nursing Students, St. Catherine University

- Chassity Speight-Washburn, MSN, RN, CNE, Stanly Community College

- Dr. Carmen Stephens, DNP, RN, MS, University of Colorado-Anschutz Medical Campus

- Dr. Suzanne H. Tang, DNP, MSN, APRN, FNP-BC, PHN, Rio Hondo College

- Forum Tihara, MSN, RN, Madison Area Technical College

- Jacquelyn R. Titus, MS, RN, Pasco Hernando State College

- Amy L. Tyznik, MSN, RN, Moraine Park Technical College

- Heidi VandenBush, MSN, RN-BC, Northeast Wisconsin Technical College

- Jennie E. Ver Steeg, MA, MS, MLS, Mercy College of Health Sciences

- Dr. Nancy Lynn Whitehead, PhD, APNP, RN, Milwaukee Area Technical College

- Dr. LaDonna Williams, DNP, RN, Lord Fairfax Community College

- Julie Woitalla, MSN, RN, Central Lakes College

Licensing/Terms of Use

This textbook is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International (CC-BY) license unless otherwise indicated, which means that you are free to:

- SHARE – copy and redistribute the material in any medium or format

- ADAPT – remix, transform, and build upon the material for any purpose, even commercially

The licensor cannot revoke these freedoms as long as you follow the license terms.

- Attribution: You must give appropriate credit, provide a link to the license, and indicate if any changes were made. You may do so in any reasonable manner, but not in any way that suggests the licensor endorses you or your use.

- No Additional Restrictions: You may not apply legal terms or technological measures that legally restrict others from doing anything the license permits.

- Notice: You do not have to comply with the license for elements of the material in the public domain or where your use is permitted by an applicable exception or limitation.

- No Warranties are Given: The license may not give you all of the permissions necessary for your intended use. For example, other rights such as publicity, privacy, or moral rights may limit how you use the material.

Attribution

Some of the content for this textbook was adapted from the following open educational resources. For specific reference information about what was used and/or changed in this adaptation, please refer to the footnotes at the bottom of each page of the book.

- Nursing Pharmacology by Chippewa Valley Technical College is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

- Nursing Skills by Chippewa Valley Technical College is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

- Anatomy and Physiology by Boundless is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0.

- Anatomy & Physiology by OpenStax is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

- Anatomy and Physiology by Rice University is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

- Clinical Procedures for Safer Care by British Columbia Institute of Technology is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

- The Complete Subjective Health Assessment by Lapum, St-Amant, Hughes, Petrie, Morrell, and Mistry is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

- Concepts of Biology – 1st Canadian Edition by Molnar & Gair is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

- Human Biology by Wakim and Grewal is licensed under CC-BY-NC 4.0.

- Human Relations by LibreTexts is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA.

- Human Development Life Span by Overstreet is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

- Human Nutrition by University of Hawai’i at Mānoa Food Science and Human Nutrition Program is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

- Introduction to Sociology by OpenStax is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

- Microbiology by OpenStax is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

- Nursing Care at the End of Life by Lowey is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0.

- The Scholarship of Writing in Nursing Education: 1st Canadian Edition by Lapum, St-Amant, Hughes, Tan, Bogdan, Dimaranan, Frantzke, and Savicevic is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0.

- StatPearls by StatPearls Publishing is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Content that is not taken from the above OER or public domain should include the following attribution statement:

Ernstmeyer, K., & Christman, E. (Eds.). (2021). Open RN Nursing Fundamentals by Chippewa Valley Technical College is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Standards & Conceptual Approach

3

The Open RN Nursing Fundamentals textbook is based on several external standards and uses a conceptual approach.

External Standards

American Nurses Association (ANA):

The ANA provides standards for professional nursing practice including nursing standards and a code of ethics for nurses.

The National Council Licensure Examination for Registered Nurses: NCLEX-PN and NCLEX-RN Test Plans

The NCLEX-RN and NCLEX-PN test plans are updated every three years to reflect fair, comprehensive, current, and entry-level nursing competency.

The National League of Nursing (NLN): Competencies for Graduates of Nursing Programs

NLN competencies guide nursing curricula to position graduates in a dynamic health care arena with practice that is informed by a body of knowledge and ensures that all members of the public receive safe, quality care.

Quality and Safety Education for Nurses (QSEN) Institute: Pre-licensure Competencies

Quality and safety competencies include knowledge, skills, and attitudes to be developed in nursing pre-licensure programs. QSEN competencies include patient-centered care, teamwork and collaboration, evidence-based practice, quality improvement, safety, and informatics.

Wisconsin State Legislature, Administrative Code Chapter N6

The Wisconsin Administrative Code governs the Registered Nursing and Practical Nursing professions in Wisconsin.

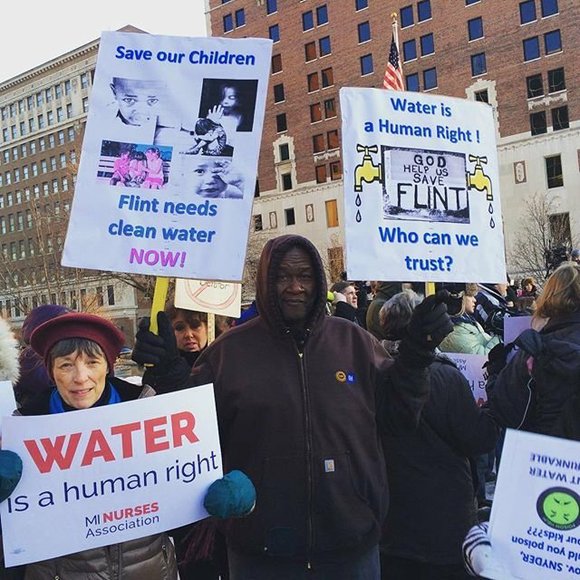

Healthy People 2030

Healthy People 2030 envisions a society in which all people can achieve their full potential for health and well-being across the life span. Healthy People provides objectives based on national data and includes social determinants of health.

Conceptual Approach

The Open RN Nursing Fundamentals textbook incorporates the following concepts across all chapters:

- Holism. Florence Nightingale taught nurses to focus on the principles of holism, including wellness and the interrelationship of human beings and their environment. This textbook encourages the application of holism by assessing the impact of developmental, emotional, cultural, religious, and spiritual influences on a patient’s health status.

- Evidence-Based Practice (EBP). Textbook content is based on current, evidence-based practices that are referenced by footnotes. To promote digital literacy, hyperlinks are provided to credible, free online resources that supplement content. The Open RN textbooks will be updated as new EBP is established and with the release of updated NCLEX Test Plans every three years.

- Cultural Competency. Nurses have an ethical and moral obligation to provide culturally competent care to the patients they serve based on the ANA Code of Ethics.American Nurses Association. (2015). Code of ethics for nurses with interpretive statements. American Nurses Association. https://www.nursingworld.org/practice-policy/nursing-excellence/ethics/code-of-ethics-for-nurses/ Cultural considerations are included throughout this textbook.

- Care Across the Life Span. Developmental stages are addressed regarding patient assessments and procedures.

- Health Promotion. Focused interview questions and patient education topics are included to promote patient well-being and encourage self-care behaviors.

- Scope of Practice. Assessment techniques are included that have been identified as frequently performed by entry-level nurse generalists.Anderson, B., Nix, E., Norman, B., & McPike, H. D. (2014). An evidence based approach to undergraduate physical assessment practicum course development. Nurse Education in Practice, 14(3), 242–246. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nepr.2013.08.007,Giddens, J., & Eddy, L. (2009). A survey of physical examination skills taught in undergraduate nursing programs: Are we teaching too much? Journal of Nursing Education, 48(1), 24–29. https://doi.org/10.3928/01484834-20090101-05,Giddens, J. (2007). A survey of physical assessment techniques performed by RNs: Lessons for nursing education. Journal of Nursing Education, 46(2), 83–87. https://doi.org/10.3928/01484834-20070201-09,Morrell, S., Ralph, J., Giannotti, N., Dayus, D., Dennison, S., & Bornais, J.(2019). Physical assessment skills in nursing curricula: A scoping review protocol. JBI Database System Rev Implement Rep., 17(6), 1086-1091. https://doi.org/10.11124/jbisrir-2017-003981.

- Patient Safety. Expected and unexpected findings on assessment are highlighted in tables to promote patient safety by encouraging notification of health care providers when changes in condition occur.

- Clear and Inclusive Language. Content is written using clear language preferred by entry-level pre-licensure nursing students to enhance understanding of complex concepts.Verkuyl, M., Lapum, J., St-Amant, O., Bregstein, J., & Hughes, M. (2020). Healthcare students’ use of an e-textbook open educational resource on vital sign measurement: A qualitative study. Open Learning: The Journal of Open, Distance and e-Learning. https://doi.org/10.1080/02680513.2020.1835623 “They” is used as a singular pronoun to refer to a person whose gender is unknown or irrelevant to the context of the usage, as endorsed by APA style. It is inclusive of all people and helps writers avoid making assumptions about gender.American Psychological Association (2021). Singular “They.” https://apastyle.apa.org/style-grammar-guidelines/grammar/singular-they

- Open Source Images and Fair Use. Images are included to promote visual learning. Students and faculty can reuse open source images by following the terms of their associated Creative Commons licensing. Some images are included based on Fair Use as described in the “Code of Best Practices for Fair Use and Fair Dealing in Open Education” presented at the OpenEd20 conference. Refer to the footnotes of images for source and licensing information throughout the text.

- Open Pedagogy. Students are encouraged to contribute to the Open RN textbooks in meaningful ways. In this textbook, students assisted in reviewing content for clarity for an entry-level learner and also assisted in creating open source images.The Open Pedagogy Notebook by Steel Wagstaff is licensed under CC BY 4.0

Supplementary Material Provided

Several supplementary resources are provided with this textbook.

- Supplementary, free videos to promote student understanding of concepts and procedures

- Sample documentation for assessments and procedures

- Online learning activities with formative feedback

- Critical thinking questions that encourage application of content to patient scenarios

- Free downloadable versions for offline use

An affordable print version of this textbook is published by XanEdu and is available on Amazon and in college bookstores. It has been reported that over 65% of students prefer a print version of their textbooks.Verkuyl, M., Lapum, J., St-Amant, O., Bregstein, J., & Hughes, M. (2020). Healthcare students’ use of an e-textbook open educational resource on vital sign measurement: A qualitative study. Open Learning: The Journal of Open, Distance and e-Learning. https://doi.org/10.1080/02680513.2020.1835623

Scope of Practice

I

1.1. Scope of Practice Introduction

Open Resources for Nursing (Open RN)

Learning Objectives

- Discuss nursing scope of practice and standards of care

- Compare various settings in which nurses work

- Describe contributions of interprofessional health care team members

- Describe levels of nursing education and the NCLEX

- Discuss basic legal considerations and ethics

- Outline professional nursing organizations

- Examine quality and evidence-based practice in nursing

You are probably wondering, “What is scope of practice? What does it mean for me and my nursing practice?” Scope of practice is defined as services that a trained health professional is deemed competent to perform and permitted to undertake according to the terms of their professional nursing license.American Nurses Association. (n.d.). Scope of practice. https://www.nursingworld.org/practice-policy/scope-of-practice/ Nursing scope of practice provides a framework and structured guidance for activities one can perform based on their nursing license. As a nurse and a nursing student, is always important to consider: Just because your employer asks you to do a task…can you perform this task according to your scope of practice – or are you putting your nursing license at risk?

Nurses must also follow legal standards in when providing nursing care. Standards are set by several organizations, including the American Nurses Association (ANA), your state’s Nurse Practice Act, agency policies and procedures, and federal regulators. These standards assure safe, competent care is provided to the public.

This chapter will provide an overview of basic concepts related to nursing scope of practice and standards of care.

1.2 History and Foundation

Open Resources for Nursing (Open RN)

Brief History of Nursing

Before discussing scope and standards of nursing care, it is helpful to briefly review a history of the nursing profession. Florence Nightingale is considered to be the founder of modern nursing practice. In 1860 she established the first nursing school in the world. By establishing this school of nursing, Nightingale promoted the concept of nurses as a professional, educated workforce of caregivers for the sick.Karimi, H., & Masoudi Alavi, N. (2015). Florence Nightingale: The mother of nursing. Nursing and Midwifery Studies, 4(2), e29475. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4557413/ See Figure 1.1“Florence Nightingale (H Hering NPG x82368).jpg” by Henry Hering (1814-1893) is in the Public Domain for a portrait of Florence Nightingale. Florence Nightingale’s contributions to health care started during the Crimean War in 1854. Her team discovered that poor health care for wounded soldiers was being delivered by overworked medical staff in a dirty environment. Florence recorded the mortality rate in the hospital and created statistical models that demonstrated that out of every 1,000 injured soldiers, 600 were dying because of preventable communicable and infectious diseases. Florence’s nursing interventions were simple; she focused on providing a clean environment, clean water, and good nutrition to promote healing, such as providing fruit as part of the care for the wounded soldiers. With these simple actions, the mortality rate of the soldiers decreased from 60% to 2.2%. In 1859 Nightingale wrote a book titled Notes on Nursing that served as the cornerstone of the Nightingale School of Nursing curriculum. Nightingale believed in the importance of placing a patient in a environment that promoted healing where they could recover from disease. She promoted this knowledge as distinct from medical knowledge. Her emphasis on the value of the environment formed many of the foundational principles that we still use in creating a healing health care setting today. She also insisted on the importance of building trusting relationships with patients and believed in the therapeutic healing that resulted from nurses’ presence with patients. She promoted the concept of confidentiality, stating a nurse “should never answer questions about her sick except to those who have a right to ask them.”Karimi, H., & Masoudi Alavi, N. (2015). Florence Nightingale: The mother of nursing. Nursing and Midwifery Studies, 4(2), e29475. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4557413/. These nursing concepts formed the foundation of nursing practice as we know it today.

Modern nursing has reinvented itself a number of times as health care has advanced and changed over the past 160 years. With more than four million members, the nursing profession represents the largest segment of the United States’ health care workforce. Nursing practice covers a broad continuum, including health promotion, disease prevention, coordination of care, and palliative care when cure is not possible. Nurses directly affect patient care and provide the majority of patient assessments, evaluations, and care in hospitals, nursing homes, clinics, schools, workplaces, and ambulatory settings. They are at the front lines in ensuring that patient care is delivered safely, effectively, and compassionately. Additionally, nurses attend to patients and their families in a holistic way that often goes beyond physical health needs and recognize social, mental, emotional, and spiritual needs.Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Initiative on the Future of Nursing, at the Institute of Medicine. (2011). The future of nursing: Leading change, advancing health. National Academies Press. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK209880/57413/

American Nurses Association (ANA)

The American Nurses Association (ANA) is a national, professional nursing organization that was established in 1896. The ANA represents the interests of nurses in all 50 states of America while also promoting improved health care for everyone. The mission of the ANA is to “lead the profession to shape the future of nursing and health care.”American Nurses Association. (n.d.). About ANA. https://www.nursingworld.org/ana/about-ana/ The ANA states that it exists to advance the nursing profession by doing the following:

- Fostering high standards of nursing practice

- Promoting a safe and ethical work environment

- Bolstering the health and wellness of nurses

- Advocating on health care issues that affect nurses and the publicAmerican Nurses Association. (n.d.). About ANA. https://www.nursingworld.org/ana/about-ana/

The ANA sets many standard of care for professional nurses that will be discussed in the next section.

Read more information about the American Nurses Association

View the Discover the American Nurses Association video.American Nurses Association. (2010, May 14). Discover the American Nurses Association (ANA). [Video]. YouTube. All rights reserved. https://youtu.be/PRwPhOjeqL4

1.3 Regulations & Standards

Open Resources for Nursing (Open RN)

Standards for nursing care are set by several organizations, including the American Nurses Association (ANA), your state’s Nurse Practice Act, agency policies and procedures, federal regulators, and other professional nursing organizations. These standards assure safe, competent care is provided to the public.

ANA Scope and Standards of Practice

The American Nurses Association (ANA) publishes two resources that set standards and guide professional nursing practice in the United States: The Code of Ethics for Nurses and Nursing: Scope and Standards of Practice. The Code of Ethics for Nurses establishes an ethical framework for nursing practice across all roles, levels, and settings. It is discussed in greater detail in the “Legal Considerations and Ethics” subsection of this chapter. The Nursing: Scope and Standards of Practice describes a professional nurse’s scope of practice and defines the who, what, where, when, why, and how of nursing. It also sets 18 standards of professional practice that all registered nurses are expected to perform competently. American Nurses Association. (2021). Nursing: Scope and standards of practice (4th ed.). American Nurses Association

The “who” of nursing practice are the nurses who have been educated, titled, and maintain active licensure to practice nursing. The “what” of nursing is the recently revised definition of nursing: “Nursing integrates the art and science of caring and focuses on the protection, promotion, and optimization of health and human functioning; prevention of illness and injury; facilitation of healing; and alleviation of suffering through compassionate presence. Nursing is the diagnosis and treatment of human responses and advocacy in the care of individuals, families, groups, communities, and populations in recognition of the connection of all humanity.”American Nurses Association. (2021). Nursing: Scope and standards of practice (4th ed.). American Nurses Association Simply put, nurses treat human responses to health problems and life processes and advocate for the care of others.

Nursing practice occurs “when” there is a need for nursing knowledge, wisdom, caring, leadership, practice, or education, anytime, anywhere. Nursing practice occurs in any environment “where” there is a health care consumer in need of care, information, or advocacy. The “why” of nursing practice is described as nursing’s response to the changing needs of society to achieve positive health care consumer outcomes in keeping with nursing’s social contract and obligation to society. The “how” of nursing practice is defined as the ways, means, methods, and manners that nurses use to practice professionally.American Nurses Association. (2021). Nursing: Scope and standards of practice (4th ed.). American Nurses Association The “how” of nursing is further defined by the standards of practice set by the ANA. There are two sets of standards, the Standards of Professional Nursing Practice and the Standards of Professional Performance.

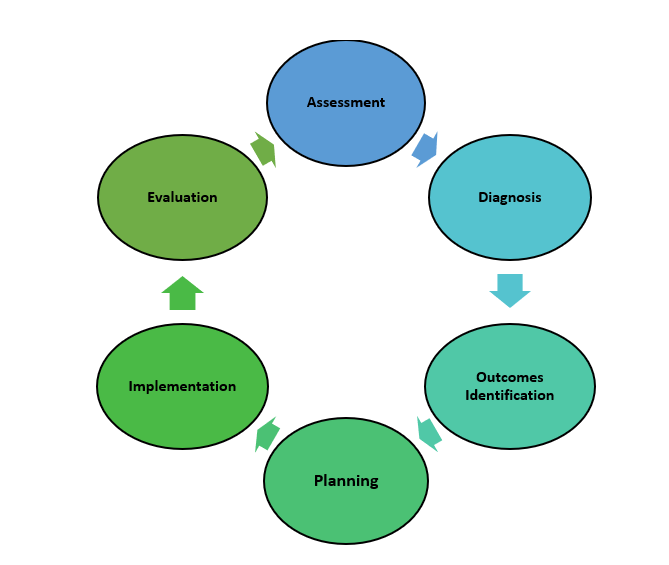

The Standards of Professional Nursing Practice are “authoritative statements of the actions and behaviors that all registered nurses, regardless of role, population, specialty, and setting, are expected to perform competently.”American Nurses Association. (2021). Nursing: Scope and standards of practice (4th ed.). American Nurses Association These standards define a competent level of nursing practice based on the critical thinking model known as the nursing process. The nursing process includes the components of assessment, diagnosis, outcomes identification, planning, implementation, and evaluation.American Nurses Association. (2021). Nursing: Scope and standards of practice (4th ed.). American Nurses Association. Each of these standards is further discussed in the “Nursing Process” chapter of this book.

The Standards of Professional Performance are 12 additional standards that describe a nurse’s professional behavior, including activities related to ethics, advocacy, respectful and equitable practice, communication, collaboration, leadership, education, scholarly inquiry, quality of practice, professional practice evaluation, resource stewardship, and environmental health. All registered nurses are expected to engage in these professional role activities based on their level of education, position, and role. Registered nurses are accountable for their professional behaviors to themselves, health care consumers, peers, and ultimately to society. American Nurses Association. (2021). Nursing: Scope and standards of practice (4th ed.). American Nurses Association. The 2021 Standards of Professional Performance are as follows:

- Ethics. The registered nurse integrates ethics in all aspects of practice.

- Advocacy. The registered nurse demonstrates advocacy in all roles and settings.

- Respectful and Equitable Practice. The registered nurse practices with cultural humility and inclusiveness.

- Communication. The registered nurse communicates effectively in all areas of professional practice.

- Collaboration. The registered nurse collaborates with the health care consumer and other key stakeholders.

- Leadership. The registered nurse leads within the profession and practice setting.

- Education. The registered nurse seeks knowledge and competence that reflects current nursing practice and promotes futuristic thinking.

- Scholarly Inquiry. The registered nurse integrates scholarship, evidence, and research findings into practice.

- Quality of Practice. The registered nurse contributes to quality nursing practice.

- Professional Practice Evaluation. The registered nurse evaluates one’s own and others’ nursing practice.

- Resource Stewardship. The registered nurse utilizes appropriate resources to plan, provide, and sustain evidence-based nursing services that are safe, effective, financially responsible, and judiciously used.

- Environmental Health. The registered nurse practices in a manner that advances environmental safety and health.American Nurses Association. (2021). Nursing: Scope and standards of practice (4th ed.). American Nurses Association.

Years ago, nurses were required to recite the Nightingale pledge to publicly confirm their commitment to maintain the profession’s high ethical and moral values: “I will do all in my power to maintain and elevate the standard of my profession and will hold in confidence all personal matters committed to my keeping and family affairs coming to my knowledge in the practice of my calling, with loyalty will I endeavor to aid the physician in his work, and devote myself to the welfare of those committed to my care.” Although some of the words are outdated, the meaning is clear: Nursing is a calling, not just a job; to answer that call, you must be dedicated to serve your community according to the ANA standards of care and code of ethics.Bostain, L. (2020, June 25). Nursing professionalism begins with you. American Nurse. https://www.myamericannurse.com/nursing-professionalism-begins-with-you/

Nurse Practice Act

In addition to the professional standards of practice and professional performance set by the American Nurses Association, nurses must legally follow regulations set by the Nurse Practice Act and enforced by the Board of Nursing in the state where they are employed. The Board of Nursing is the state-specific licensing and regulatory body that sets standards for safe nursing care and issues nursing licenses to qualified candidates, based on the Nurse Practice Act enacted by that state’s legislature. The Nurse Practice Act establishes regulations for nursing practice within that state and defines the scope of nursing practice. If nurses do not follow the standards and scope of practice set forth by the Nurse Practice Act, they can have their nursing license revoked by the Board of Nursing.

To read more about the the Wisconsin Board of Nursing, Standards of Practice, and Rules of Conduct, use the hyperlinked PDFs provided below.Wisconsin Administrative Code. (2018). Chapter N 6 standards of practice for registered nurses and licensed practical nurses. https://docs.legis.wisconsin.gov/code/admin_code/n/6.pdf

Read more details about the Wisconsin Administrative Code and the Board of Nursing.

Read about Wisconsin Standards of Practice for Nurses in Chapter N 6.

Read about Wisconsin Rules of Conduct in Chapter N 7.

Nursing students must understand their scope of practice outlined in their state’s Nurse Practice Act. Nursing students are legally accountable for the quality of care they provide to patients just as nurses are accountable. Students are expected to recognize the limits of their knowledge and experience and appropriately alert individuals in authority regarding situations that are beyond their competency. A violation of the standards of practice constitutes unprofessional conduct and can result in the Board of Nursing denying a license to a nursing graduate.

Employer Policies, Procedures, and Protocols

In addition to professional nursing standards set by the American Nurses Association and the state Nurse Practice Act where they work, nurses and nursing students must also practice according to agency policies, procedures, and protocols. For example, hospitals often set a policy that requires a thorough skin assessment must be completed and documented daily on every patient. If a nurse did not follow this policy and a patient developed a pressure injury, the nurse could be held liable. In addition, every agency has their own set of procedures and protocols that a nurse and nursing student must follow. For example, each agency has specific procedural steps for performing nursing skills, such as inserting urinary catheters. A protocol is defined by the Wisconsin Nurse Practice Act as a “precise and detailed written plan for a regimen of therapy.” For example, agencies typically have a hypoglycemia protocol that nurses automatically implement when a patient’s blood sugar falls below a specific number. The hypoglycemia protocol includes actions such as providing orange juice and rechecking the blood sugar. These agency-specific policies, procedures, and protocols supersede the information taught in nursing school, and nurses and nursing students can be held legally liable if they don’t follow them. Therefore, it is vital for nurses and nursing students to always review and follow current agency-specific procedures, policies, and protocols when providing patient care.

Nurses and nursing students must continue to follow their scope of practice as defined by the Nurse Practice Act in the state they are practicing when following agency policies, procedures, and protocols. Situations have occurred when a nurse or nursing student was asked by an agency to do something outside their defined scope of practice that impaired their nursing license. It is always up to you to protect your nursing license and follow the state’s Nurse Practice Act when providing patient care.

Federal Regulations

In addition to nursing scope of practice and standards being defined by the American Nurses Association, state Nurse Practice Acts, and employer policies, procedures, and protocols, nursing practice is also influenced by federal regulations enacted by agencies such as the Joint Commission and the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid.

The Joint Commission

The Joint Commission is a national organization that accredits and certifies over 20,000 health care organizations in the United States. The mission of The Joint Commission (TJC) is to continuously improve health care for the public by inspiring health care organizations to excel in providing safe and effective care of the highest quality and value.The Joint Commission. (n.d.). https://www.jointcommission.org/ The Joint Commission sets standards for providing safe, high-quality health care.

National Patient Safety Goals

The Joint Commission establishes annual National Patient Safety Goals for various types of agencies based on data regarding current national safety concerns.The Joint Commission. (n.d.). National patient safety goals. https://www.jointcommission.org/standards/national-patient-safety-goals/ For example, National Patient Safety Goals for hospitals include the following:

- Identify Patients Correctly

- Improve Staff Communication

- Use Medicines Safely

- Use Alarms Safely

- Prevent Infection

- Identify Patient Safety Risks

- Prevent Mistakes in Surgery

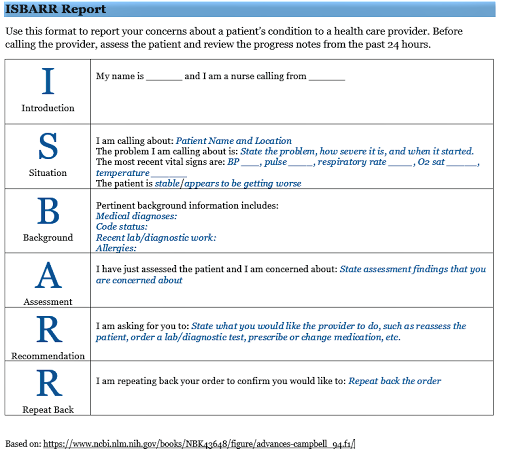

Nurses, nursing students, and other staff members are expected to incorporate actions related to these safety goals into their daily patient care. For example, SBAR (Situation, Background, Assessment, and Recommendation) handoff reporting techniques, bar code scanning equipment, and perioperative team “time-outs” prior to surgery are examples of actions incorporated at agencies based on National Patient Safety Goals. Nursing programs also use National Patient Safety Goals to guide their curriculum and clinical practice expectations. National Patient Safety Goals are further discussed in the “Safety” chapter of this book.

Use the hyperlinks provided below to read more about The Joint Commission and National Patient Safety Goals.

Joint Commission Center for Transforming Healthcare

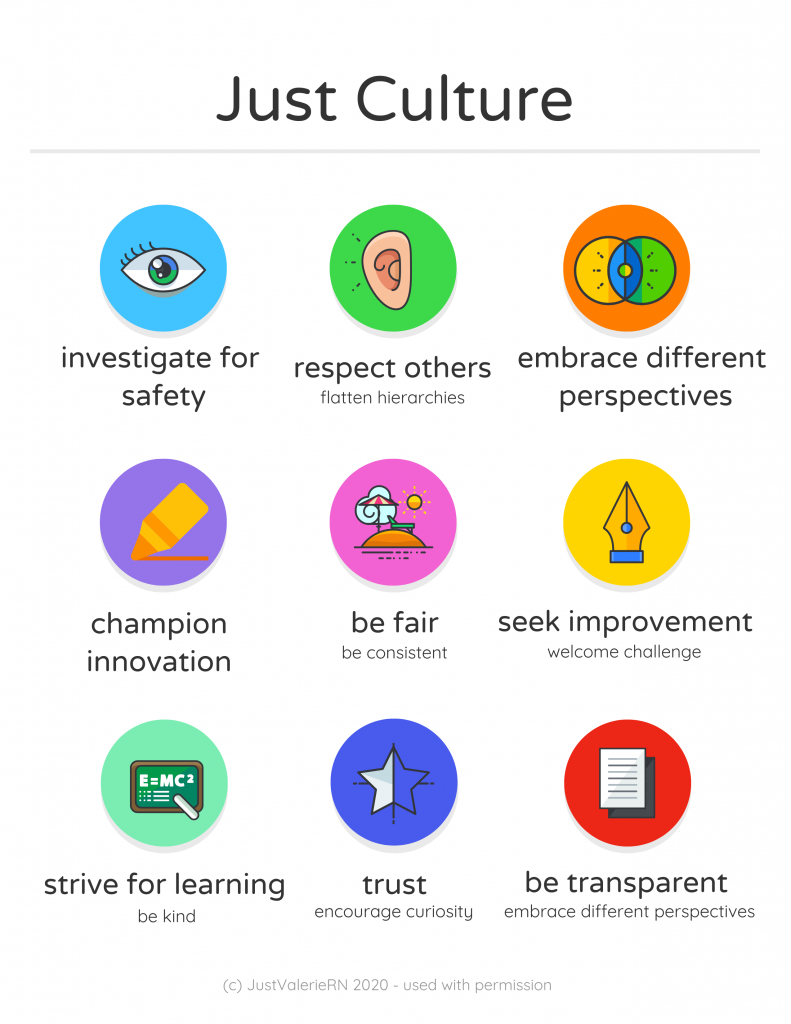

The Joint Commission Center for Transforming Healthcare was developed in 2008 to help agencies develop effective solutions for critical safety problems with a goal to ultimately achieve zero harm to patients. Some of the projects the Center has developed include improved hand hygiene, effective handoff communications, and safe and effective use of insulin. The Center has also been instrumental in creating a focus on a safety culture in health care organizations. A safety culture empowers nurses, nursing students, and other staff members to speak up about their concerns about patient risks and to report errors and near misses, all of which drive improvement in patient care and reduce the incidences of patient harm.Joint Commission Center for Transforming Healthcare. (n.d.). Creating a safety culture. https://www.centerfortransforminghealthcare.org/why-work-with-us/video-resources/creating-a-safety-culture Many health care agencies have implemented a safety culture in their workplace and successfully reduced incidences of patient harm. An example of a safety culture action is a nurse or nursing student creating an incident report when an error occurs when administering medication. The incident report is used by the agency to investigate system factors that contribute to errors. To read more about creating a safety culture, use the hyperlink provided below.

Read more about Creating a Safety Culture.

Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services

The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) is another federal agency that establishes regulations that affect nursing care. CMS is a part of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) that administers the Medicare program and works in partnership with state governments to administer Medicaid. The CMS establishes and enforces regulations to protect patient safety in hospitals that receive Medicare and Medicaid funding. For example, one CMS regulation states that a hospital’s policies and procedures must require confirmation of specific information before medication is administered to patients. This CMS regulation is often referred to as “checking the rights of medication administration.” You can read more information about checking the rights of medication administration in the “Administration of Enteral Medications” chapter of the Open RN Nursing Skills textbook.This work is a derivative of Nursing Skills by Open RN and is licensed under CC BY 4.0

CMS also enforces quality standards in health care organizations that receive Medicare and Medicaid funding. These organizations are reimbursed based on the quality of their patient outcomes. For example, organizations with high rates of healthcare-associated infections (HAI) receive less reimbursement for services they provide. As a result, many agencies have reexamined their policies, procedures, and protocols to promote optimal patient outcomes and maximum reimbursement.

Now that we have discussed various agencies that affect a nurse’s scope and standards of practice, let’s review various types of health care settings where nurses work and members of the health care team.

1.4 Health Care Settings & Team

Open Resources for Nursing (Open RN)

Health Care Settings

There are several levels of health care including primary, secondary, and tertiary care. Each of these levels focuses on different aspects of health care and is typically provided in different settings.

Primary Care

Primary care promotes wellness and prevents disease. This care includes health promotion, education, protection (such as immunizations), early disease screening, and environmental considerations. Settings providing this type of health care include physician offices, public health clinics, school nursing, and community health nursing.

Secondary care

Secondary care occurs when a person has contracted an illness or injury and requires medical care. Secondary care is often referred to as acute care. Secondary care can range from uncomplicated care to repair a small laceration or treat a strep throat infection to more complicated emergent care such as treating a head injury sustained in an automobile accident. Whatever the problem, the patient needs medical and nursing attention to return to a state of health and wellness. Secondary care is provided in settings such as physician offices, clinics, urgent care facilities, or hospitals. Specialized units include areas such as burn care, neurosurgery, cardiac surgery, and transplant services.

Tertiary Care

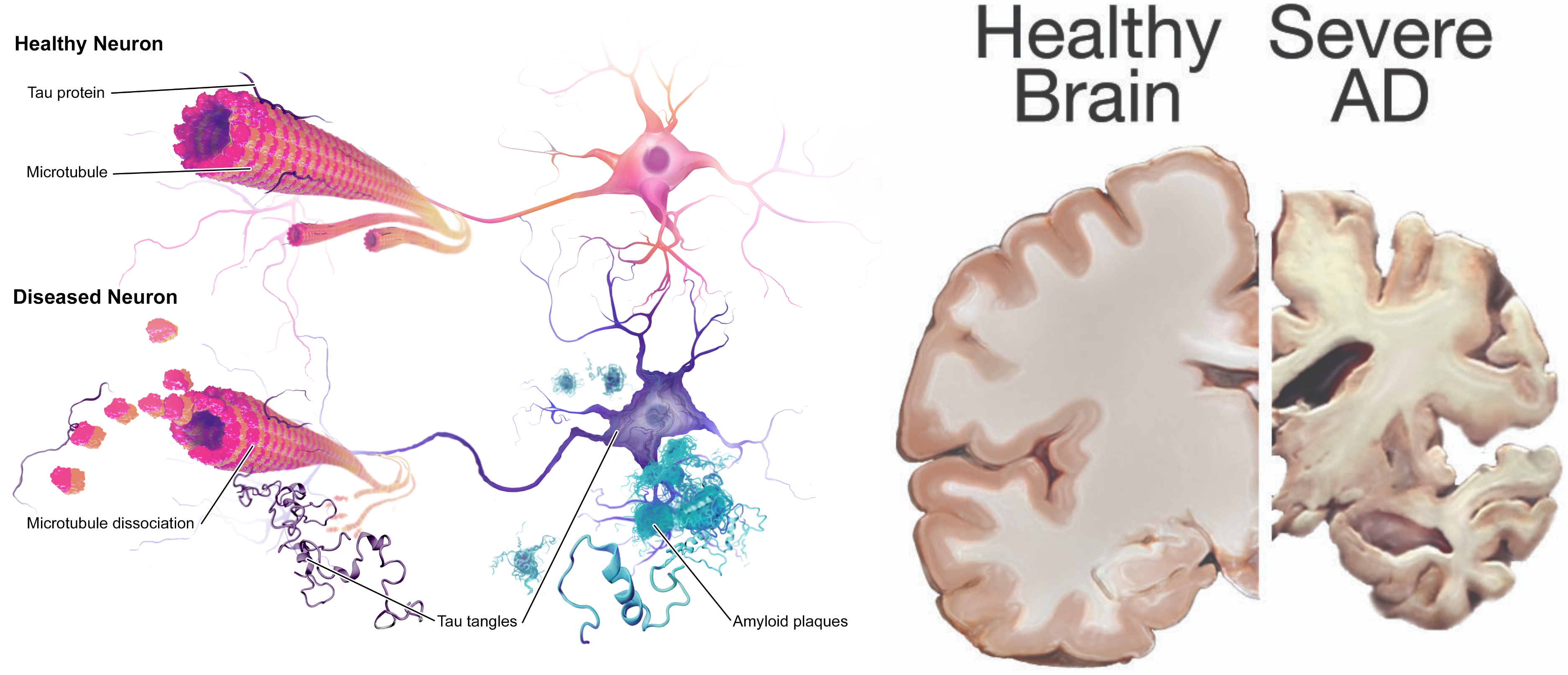

Tertiary care addresses the long-term effects from chronic illnesses or conditions with the purpose to restore a patient’s maximum physical and mental function. The goal of tertiary care is to achieve the highest level of functioning possible while managing the chronic illness. For example, a patient who falls and fractures their hip will need secondary care to set the broken bones, but may need tertiary care to regain their strength and ability to walk even after the bones have healed. Patients with incurable diseases, such as dementia, may need specialized tertiary care to provide support they need for daily functioning. Tertiary care settings include rehabilitation units, assisted living facilities, adult day care, skilled nursing units, home care, and hospice centers.

Health Care Team

No matter the setting, quality health care requires a team of health care professionals collaboratively working together to deliver holistic, individualized care. Nursing students must be aware of the roles and contributions of various health care team members. The health care team consists of health care providers, nurses (licensed practical nurses, registered nurses, and advanced registered nurses), unlicensed assistive personnel, and a variety of interprofessional team members.

Health Care Providers

The Wisconsin Nurse Practice Act defines a provider as, “A physician, podiatrist, dentist, optometrist, or advanced practice nurse.”Wisconsin Administrative Code. (2018). Chapter N 6 standards of practice for registered nurses and licensed practical nurses. https://docs.legis.wisconsin.gov/code/admin_code/n/6.pdf Providers are responsible for ordering diagnostic tests such as blood work and X-rays, diagnosing a patient’s medical condition, developing a medical treatment plan, and prescribing medications. In a hospital setting, the medical treatment plan developed by a provider is communicated in the “History and Physical” component of the patient’s medical record with associated prescriptions (otherwise known as “orders”). Prescriptions or “orders” include diagnostic and laboratory tests, medications, and general parameters regarding the care that each patient is to receive. Nurses should respectfully clarify prescriptions they have questions or concerns about to ensure safe patient care. Providers typically visit hospitalized patients daily in what is referred to as “rounds.” It is helpful for nurses and nursing students to attend provider rounds for their assigned patients to be aware of and provide input regarding the current medical treatment plan, seek clarification, or ask questions. This helps to ensure that the provider, nurse, and patient have a clear understanding of the goals of care and minimize the need for follow-up phone calls.

Nurses

There are three levels of nurses as defined by each state’s Nurse Practice Act: Licensed Practical Nurse/Vocational Nurse (LPN/LVN), Registered Nurse (RN), and Advanced Practice Nurse (APRN).

Licensed Practical/Vocational Nurses

The NCSBN defines a licensed practical nurse (LPN) as, “An individual who has completed a state-approved practical or vocational nursing program, passed the NCLEX-PN examination, and is licensed by a state board of nursing to provide patient care.”NCSBN. https://www.ncsbn.org/ In some states, the term licensed vocational nurse (LVN) is used. LPN/LVNs typically work under the supervision of a registered nurse, advanced practice registered nurse, or physician.NCSBN. https://www.ncsbn.org/index.htm LPNs provide “basic nursing care” and work with stable and/or chronically ill populations. Basic nursing care is defined by the Wisconsin Nurse Practice Act as “care that can be performed following a defined nursing procedure with minimal modification in which the responses of the patient to the nursing care are predictable.”Wisconsin Administrative Code. (2018). Chapter N 6 standards of practice for registered nurses and licensed practical nurses. https://docs.legis.wisconsin.gov/code/admin_code/n/6.pdf LPN/LVNs typically collect patient assessment information, administer medications, and perform nursing procedures according to their scope of practice in that state. The Open RN Nursing Skills textbook discusses the skills and procedures that LPNs frequently perform in Wisconsin. See the following box for additional details about the scope of practice of the Licensed Practical Nurse in Wisconsin.

Scope of Practice for Licensed Practical Nurses in Wisconsin

The Wisconsin Nurse Practice Act defines the scope of practice for Licensed Practical Nurses as the following: “In the performance of acts in basic patient situations, the LPN shall, under the general supervision of an RN or the direction of a provider:

(a) Accept only patient care assignments which the LPN is competent to perform.

(b) Provide basic nursing care.

(c) Record nursing care given and report to the appropriate person changes in the condition of a patient.

(d) Consult with a provider in cases where an LPN knows or should know a delegated act may harm a patient.

(e) Perform the following other acts when applicable:

- Assist with the collection of data.

- Assist with the development and revision of a nursing care plan.

- Reinforce the teaching provided by an RN provider and provide basic health care instruction.

- Participate with other health team members in meeting basic patient needs.”Wisconsin Administrative Code. (2018). Chapter N 6 standards of practice for registered nurses and licensed practical nurses. https://docs.legis.wisconsin.gov/code/admin_code/n/6.pdf

Registered Nurses

The NCSBN defines a Registered Nurse as “An individual who has graduated from a state-approved school of nursing, passed the NCLEX-RN examination and is licensed by a state board of nursing to provide patient care.”NCSBN. https://www.ncsbn.org/index.htm Registered Nurses (RNs) use the nursing process as a critical thinking model as they make decisions and use clinical judgment regarding patient care. The nursing process is discussed in more detail in the “Nursing Process” chapter of this book. RNs may be delegated tasks from providers or may delegate tasks to LPNs and UAPs with supervision. See the following box for additional details about the scope of practice for Registered Nurses in the state of Wisconsin.

Scope of Practice for Registered Nurses in Wisconsin

(1) GENERAL NURSING PROCEDURES. An RN shall utilize the nursing process in the execution of general nursing procedures in the maintenance of health, prevention of illness or care of the ill. The nursing process consists of the steps of assessment, planning, intervention, and evaluation. This standard is met through performance of each of the following steps of the nursing process:

(a) Assessment. Assessment is the systematic and continual collection and analysis of data about the health status of a patient culminating in the formulation of a nursing diagnosis.

(b) Planning. Planning is developing a nursing plan of care for a patient, which includes goals and priorities derived from the nursing diagnosis.

(c) Intervention. Intervention is the nursing action to implement the plan of care by directly administering care or by directing and supervising nursing acts delegated to LPNs or less skilled assistants.

(d) Evaluation. Evaluation is the determination of a patient’s progress or lack of progress toward goal achievement, which may lead to modification of the nursing diagnosis.

(2) PERFORMANCE OF DELEGATED ACTS. In the performance of delegated acts, an RN shall do all of the following:

(a) Accept only those delegated acts for which there are protocols or written or verbal orders.

(b) Accept only those delegated acts for which the RN is competent to perform based on his or her nursing education, training or experience.

(c) Consult with a provider in cases where the RN knows or should know a delegated act may harm a patient.

(d) Perform delegated acts under the general supervision or direction of provider.

(3) SUPERVISION AND DIRECTION OF DELEGATED ACTS. In the supervision and direction of delegated acts, an RN shall do all of the following:

(a) Delegate tasks commensurate with educational preparation and demonstrated abilities of the person supervised.

(b) Provide direction and assistance to those supervised.

(c) Observe and monitor the activities of those supervised.

(d) Evaluate the effectiveness of acts performed under supervision.Wisconsin Administrative Code. (2018). Chapter N 6 standards of practice for registered nurses and licensed practical nurses. https://docs.legis.wisconsin.gov/code/admin_code/n/6.pdf

Advanced Practice Nurses

Advanced Practice Nurses (APRN) are defined by the NCSBN as an RN who has a graduate degree and advanced knowledge. There are four categories of Advanced Practice Nurses: certified nurse-midwife (CNM), clinical nurse specialist (CNS), certified nurse practitioner (CNP), and certified registered nurse anesthetist (CRNA). APRNs can diagnose illnesses and prescribe treatments and medications. Additional information about advanced nursing degrees and roles is provided in the box below.

Advanced Practice Nursing RolesInstitute of Medicine (US) Committee on the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Initiative on the Future of Nursing at the Institute of Medicine. (2011). The future of nursing: Leading change, advancing health. National Academies Press. https://www.nap.edu/catalog/12956/the-future-of-nursing-leading-change-advancing-health

Nurse Practitioners: Nurse practitioners (NPs) work in a variety of settings and complete physical examinations, diagnose and treat common acute illness and manage chronic illness, order laboratory and diagnostic tests, prescribe medications and other therapies, provide health teaching and supportive counseling with an emphasis on prevention of illness and health maintenance, and refer patients to other health professionals and specialists as needed. In many states, NPs can function independently and manage their own clinics, whereas in other states physician supervision is required. NP certifications include, but are not limited to, Family Practice, Adult-Gerontology Primary Care and Acute Care, and Psychiatric/Mental Health.

To read more about NP certification, visit Nursing World’s Our Certifications web page.

Clinical Nurse Specialists: Clinical Nurse Specialists (CNS) practice in a variety of health care environments and participate in mentoring other nurses, case management, research, designing and conducting quality improvement programs, and serving as educators and consultants. Specialty areas include, but are not limited to, Adult/Gerontology, Pediatrics, and Neonatal.

To read more about CNS certification, visit NACNS’s What is a CNS? web page.

Certified Registered Nurse Anesthetists: Certified Registered Nurse Anesthetists (CRNAs) administer anesthesia and related care before, during, and after surgical, therapeutic, diagnostic, and obstetrical procedures, as well as provide airway management during medical emergencies. CRNAs deliver more than 65 percent of all anesthetics to patients in the United States. Practice settings include operating rooms, dental offices, and outpatient surgical centers.

To read more about CRNA certification, visit NBCRNA’s website.

Certified Nurse Midwives: Certified Nurse Midwives provide gynecological exams, family planning advice, prenatal care, management of low-risk labor and delivery, and neonatal care. Practice settings include hospitals, birthing centers, community clinics, and patient homes.

To read more about CNM certification, visit AMCB Midwife’s website.

Unlicensed Assistive Personnel

Unlicensed Assistive Personnel (UAP) are defined by the NCSBN as, “Any unlicensed person, regardless of title, who performs tasks delegated by a nurse. This includes certified nursing aides/assistants (CNAs), patient care assistants (PCAs), patient care technicians (PCTs), state tested nursing assistants (STNAs), nursing assistants-registered (NA/Rs), or certified medication aides/assistants (MA-Cs). Certification of UAPs varies between jurisdictions.”NCSBN. https://www.ncsbn.org/index.htm

CNAs, PCAs, and PCTs in Wisconsin generally work in hospitals and long-term care facilities and assist patients with daily tasks such as bathing, dressing, feeding, and toileting. They may also collect patient information such as vital signs, weight, and input/output as delegated by the nurse. The RN remains accountable that delegated tasks have been completed and documented by the UAP.

Interprofessional Team Members

Nurses, as the coordinator of a patient’s care, continuously review the plan of care to ensure all contributions of the multidisciplinary team are moving the patient toward expected outcomes and goals. The roles and contributions of interprofessional health care team members are further described in the following box.

Interprofessional Team Member RolesBurke, A. (2020, January 15). Collaboration with interdisciplinary team: NCLEX-RN. RegisteredNursing.org. https://www.registerednursing.org/nclex/collaboration-interdisciplinary-team/#collaborating-healthcare-members-disciplines-providing-client-care

Dieticians: Dieticians assess, plan, implement, and evaluate interventions including those relating to dietary needs of those patients who need regular or therapeutic diets. They also provide dietary education and work with other members of the health care team when a client has dietary needs secondary to physical disorders such as dysphagia.

Occupational Therapists (OT): Occupational therapists assess, plan, implement, and evaluate interventions, including those that facilitate the patient’s ability to achieve their highest possible level of independence in their activities of daily living such as bathing, grooming, eating, and dressing. They also provide patients adaptive devices such as long shoe horns so the patient can put their shoes on, sock pulls so they can independently pull on socks, adaptive silverware to facilitate independent eating, grabbers so the patient can pick items up from the floor, and special devices to manipulate buttoning so the person can dress and button their clothing independently. Occupational therapists also assess the home for safety and the need for assistive devices when the patient is discharged home. They may recommend modifications to the home environment such as ramps, grab rails, and handrails to ensure safety and independence. Like physical therapists, occupational therapists practice in all health care environments including the home, hospital, and rehabilitation centers.

Pharmacists: Pharmacists ensure the safe prescribing and dispensing of medication and are a vital resource for nurses with questions or concerns about medications they are administering to patients. Pharmacists ensure that patients not only get the correct medication and dosing, but also have the guidance they need to use the medication safely and effectively.

Physical Therapists (PT): Physical therapists are licensed health care professionals who assess, plan, implement, and evaluate interventions including those related to the patient’s functional abilities in terms of their strength, mobility, balance, gait, coordination, and joint range of motion. They supervise prescribed exercise activities according to a patient’s condition and also provide and teach patients how to use assistive aids like walkers and canes and exercise regimens. Physical therapists practice in all health care environments including the home, hospital, and rehabilitation centers.

Podiatrists: Podiatrists provide care and services to patients who have foot problems. They often work with diabetic patients to clip toenails and provide foot care to prevent complications.

Prosthetists: Prosthetists design, fit, and supply the patient with an artificial body part such as a leg or arm prosthesis. They adjust prosthesis to ensure proper fit, patient comfort, and functioning.

Psychologists and Psychiatrists: Psychologists and psychiatrists provide mental health and psychiatric services to patients with mental health disorders and provide psychological support to family members and significant others as indicated.

Respiratory Therapists: Respiratory therapists treat respiratory-related conditions in patients. Their specialized respiratory care includes managing oxygen therapy; drawing arterial blood gases; managing patients on specialized oxygenation devices such as mechanical ventilators, CPAP, and Bi-PAP machines; administering respiratory medications like inhalers and nebulizers; intubating patients; assisting with bronchoscopy and other respiratory-related diagnostic tests; performing pulmonary hygiene measures like chest physiotherapy; and serving an integral role during cardiac and respiratory arrests.

Social Workers: Social workers counsel patients and provide psychological support, help set up community resources according to patients’ financial needs, and serve as part of the team that ensures continuity of care after the person is discharged.

Speech Therapists: Speech therapists assess, diagnose, and treat communication and swallowing disorders. For example, speech therapists help patients with a disorder called expressive aphasia. They also assist patients with using word boards and other electronic devices to facilitate communication. They assess patients with swallowing disorders called dysphagia and treat them in collaboration with other members of the health care team including nurses, dieticians, and health care providers.

Ancillary Department Members: Nurses also work with ancillary departments such as laboratory and radiology departments. Clinical laboratory departments provide a wide range of laboratory procedures that aid health care providers to diagnose, treat, and manage patients. These laboratories are staffed by medical technologists who test biological specimens collected from patients. Examples of laboratory tests performed include blood tests, blood banking, cultures, urine tests, and histopathology (changes in tissues caused by disease).This work is a derivative of StatPearls by Bayot and Naidoo and licensed under CC BY 4.0Radiology departments use imaging to assist providers in diagnosing and treating diseases seen within the body. They perform diagnostic tests such as X-rays, CTs, MRIs, nuclear medicine, PET scans, and ultrasound scans.

Chain of Command

Nurses rarely make patient decisions in isolation, but instead consult with other nurses and interprofessional team members. Concerns and questions about patient care are typically communicated according to that agency’s chain of command. In the military, chain of command refers to a hierarchy of reporting relationships – from the bottom to the top of an organization – regarding who must answer to whom. The chain of command not only establishes accountability, but also lays out lines of authority and decision-making power. The chain of command also applies to health care. For example, a registered nurse in a hospital may consult a “charge nurse,” who may consult the “nurse supervisor,” who may consult the “director of nursing,” who may consult the “vice president of nursing.” In a long-term care facility, a licensed practical/vocational nurse typically consults the registered nurse/charge nurse, who may consult with the director of nursing. Nursing students should always consult with their nursing instructor regarding questions or concerns about patient care before “going up the chain of command.”

Nurse Specialties

Registered nurses can obtain several types of certifications as a nurse specialist. Certification is the formal recognition of specialized knowledge, skills, and experience demonstrated by the achievement of standards identified by a nursing specialty. See the following box for descriptions of common nurse specialties.

Common Nurse Specialties

Critical Care Nurses provide care to patients with serious, complex, and acute illnesses or injuries that require very close monitoring and extensive medication protocols and therapies. Critical care nurses most often work in intensive care units of hospitals.

Public Health Nurses work to promote and protect the health of populations based on knowledge from nursing, social, and public health sciences. Public Health Nurses most often work in municipal and state health departments.

Home Health/Hospice Nurses provide a variety of nursing services for chronically ill patients and their caregivers in the home, including end-of-life care.

Occupational/Employee Health Nurses provide health screening, wellness programs and other health teaching, minor treatments, and disease/medication management services to people in the workplace. The focus is on promotion and restoration of health, prevention of illness and injury, and protection from work-related and environmental hazards.

Oncology Nurses care for patients with various types of cancer, administering chemotherapy and providing follow-up care, teaching, and monitoring. Oncology nurses work in hospitals, outpatient clinics, and patients’ homes.

Perioperative/Operating Room Nurses provide preoperative and postoperative care to patients undergoing anesthesia or assist with surgical procedures by selecting and handling instruments, controlling bleeding, and suturing incisions. These nurses work in hospitals and outpatient surgical centers.

Rehabilitation Nurses care for patients with temporary and permanent disabilities within inpatient and outpatient settings such as clinics and home health care.

Psychiatric/Mental Health Nurses specialize in mental and behavioral health problems and provide nursing care to individuals with psychiatric disorders. Psychiatric nurses work in hospitals, outpatient clinics, and private offices.

School Nurses provide health assessment, intervention, and follow-up to maintain school compliance with health care policies and ensure the health and safety of staff and students. They administer medications and refer students for additional services when hearing, vision, and other issues become inhibitors to successful learning.

Other common specialty areas include a life span approach across health care settings and include maternal-child, neonatal, pediatric, and gerontological nursing.Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Initiative on the Future of Nursing at the Institute of Medicine. (2011). The future of nursing: Leading change, advancing health. National Academies Press. https://www.nap.edu/catalog/12956/the-future-of-nursing-leading-change-advancing-health

Now that we have discussed various settings where nurses work and various nursing roles, let’s review levels of nursing education and the national licensure exam (NCLEX).

1.5 Nursing Education and the NCLEX

Open Resources for Nursing (Open RN)

Nursing Education and the NCLEX

Everyone who wants to become a nurse has a story to tell about why they want to enter the nursing profession. What is your story? Perhaps it has been a lifelong dream to become a Life Flight nurse, or maybe you became interested after watching a nurse help you or a family member through the birth of a baby, heal from a challenging illness, or assist a loved one at the end of life. Whatever the reason, everyone who wants to become a nurse must do two things: graduate from a state-approved nursing program and pass the National Council Licensure Exam (known as the NCLEX).

Nursing Programs

There are several types of nursing programs you can attend to become a nurse. If your goal is to become a Licensed Practical Nurse (LPN), you must successfully complete a one-year nursing program, pass the NCLEX-PN exam, and apply to your state board of nursing to receive a LPN license.

If you want to become a Registered Nurse, you can obtain either a two-year associate degree (ADN) or a four-year baccalaureate of science in nursing degree (BSN). Associate degree nursing graduates often enroll into a baccalaureate or higher degree program after they graduate. Many hospitals hire ADN nurses on a condition they complete their BSN within a specific time frame. A BSN is required for military nursing, case management, public health nursing, and school-based nursing services. Another lesser-known option to become an RN is to complete a three-year hospital-based diploma program, which was historically the most common way to become a nurse. Diploma programs have slowly been replaced by college degrees, and now only nine states offer this option.NCSBN. (2019). 2018 NCLEX examination statistics 77. https://www.ncsbn.org/2018_NCLEXExamStats.pdf After completing a diploma program, associate degree, or baccalaureate degree, nursing graduates must successfully pass the NCLEX-RN to apply for a registered nursing license from their state’s Board of Nursing.

NCLEX

Nursing graduates must successfully pass the National Council Licensure Examination (NCLEX) to receive a nursing license. Registered nurses must successfully pass the NCLEX-RN exam, and Licensed Practical Nurses (LPNs) or Licensed Vocational Nurses (LVNs) must pass the NCLEX-PN exam.

The NCLEX-PN and NCLEX-RN are online, adaptive tests taken at a specialized testing center. The NCLEX tests knowledge, skills, and abilities essential to the safe and effective practice of nursing at the entry level. NCLEX exams are continually reviewed and updated based on surveys of newly graduated nurses every three years.

Both the NCLEX-RN and the NCLEX-PN are variable length tests that adapt as you answer the test items. The NCLEX-RN examination can be anywhere from 75 to 265 items, depending on how quickly you are able to demonstrate your proficiency. Of these items, 15 are unscored test items. The time limit for this examination is six hours. The NCLEX-PN examination can be anywhere from 85 to 205 items. Of these items, 25 are unscored items. The time limit for this examination is five hours.NCSBN. (2019). NCLEX & Other Exams. https://www.ncsbn.org/nclex.htm

In 2023, the Next Generation NCLEX (NGN) is anticipated to go into effect. Examination questions on the NGN will use the new Clinical Judgment Measurement Model as a framework to measure prelicensure nursing graduates’ clinical judgment and decision-making. The critical thinking model called the “Nursing Process” (discussed in Chapter 4 of this book) will continue to underlie the NGN, but candidates will notice new terminology used to assess their decision-making. For example, candidates may be asked to “recognize cues,” “analyze cues,” “create a hypothesis,” “prioritize hypotheses,” “generate solutions,” “take actions,” or “evaluate outcomes.”NCSBN. (2021). NCSBN Next Generation NCLEX Project. https://www.ncsbn.org/next-generation-nclex.htm For this reason, many of the case studies and learning activities included in this book will use similar terminology as the NGN.

There will also be new types of examination questions on the NGN, including case studies, enhanced hot spots, drag and drop ordering of responses, multiple responses, and embedded answer choices within paragraphs of text. View sample NGN questions in the following hyperlink. NCSBN’s rationale for including these types of questions is to “measure the nursing clinical judgment and decision-making ability of prospective entry-level nurses to protect the public’s health and welfare by assuring that safe and competent nursing care is provided by licensed nurses.”NCSBN. (2021). NCSBN Next Generation NCLEX Project. https://www.ncsbn.org/next-generation-nclex.htm Similar questions have been incorporated into learning activities throughout this textbook.

Use the hyperlinks below to read more information about the NCLEX and the Next Generation NCLEX.

Read more information about the NCLEX & Test Plans.

Review sample Next Generation NCLEX questions at https://www.ncsbn.org/NGN-Sample-Questions.pdf.

Nurse Licensure Compact

The Nurse Licensure Compact (NLC) allows a nurse to have one multistate nursing license with the ability to practice in their home state, as well as in other compact states. As of 2020, 33 states have implemented NLC legislation.

Read additional details about the Nurse Licensure Compact.

Advanced Nursing Degrees

After obtaining an RN license, nurses can receive advanced degrees to expand their opportunities in the nursing profession.

Master’s Degree in Nursing

A Master’s of Science in Nursing Degree (MSN) requires additional credits and years of schooling beyond the BSN. There are a variety of potential focuses in this degree, including Nurse Educator and Advanced Practice Nurse (APRN). Certifications associated with an MSN degree are Certified Nurse Educator (CNE), Nurse Practitioner (NP), Clinical Nurse Specialist (CNS), Certified Registered Nurse Anesthetist (CRNA), and Certified Nurse Midwife (CNM). Certifications require the successful completion of a certification exam, as well as continuing education requirements to maintain the certification. Scope of practice for advanced practice nursing roles is defined by each state’s Nurse Practice Act.

Doctoral Degrees in Nursing

Doctoral nursing degrees include the Doctor of Philosophy in Nursing (PhD) and the Doctor of Nursing Practice (DNP). PhD-prepared nurses complete doctoral work that is focused on research. They often teach in a university setting or environment to conduct research. DNP-prepared nurses complete doctoral work that is focused on clinical nursing practice. They typically have work roles in advanced nursing practice, clinical leadership, or academic settings.

Lifelong Learning

No matter what nursing role or level of nursing education you choose, nursing practice changes rapidly and is constantly updated with new evidence-based practices. Nurses must commit to lifelong learning to continue to provide safe, quality care to their patients. Many states require continuing education credits to renew RN licenses, whereas others rely on health care organizations to set education standards and ongoing educational requirements.

Now that we have discussed nursing roles and education, let’s review legal and ethical considerations in nursing.

1.6 Legal Considerations & Ethics

Open Resources for Nursing (Open RN)

Legal Considerations