9 Module 2 – Human-Centered Design

Learning Objectives

- Explain how curricular problem-solving differs from problem-solving in the real world

- Define Human-Centered Design

- Apply Empathy, the first stage in Human-Centered Design in understanding a problem

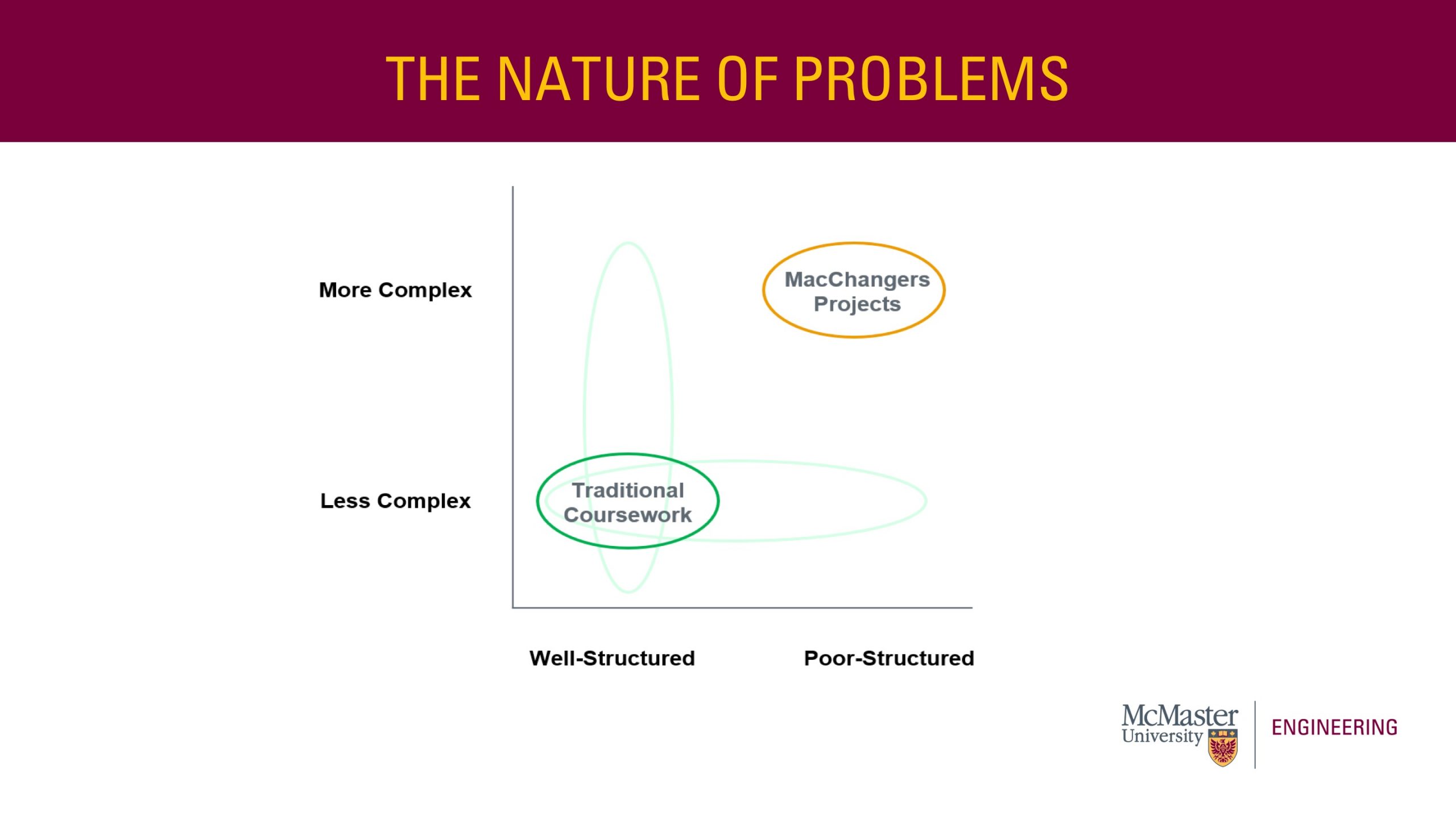

When we look at the nature of problems, there are two main elements, including Structure and Complexity. The complexity of a problem is related to the number of variables involved. For example, if you are in a STEM field, then you are used to solving problems in which there is one unknown variable, and you use everything you know to find that variable. But with complex problems, you are working with many unknown variables and so it becomes a lot harder to pin down a ‘solution’. Essentially, the less that is known, and the more variables there are, the more complex and difficult the problems become.

The second core element of a problem is structure. You can measure structure with the coherence of the variables. So what do I mean by that? If you and a friend and working on a problem, the problem would be well-structured if you can both look at the information provided and agree on the interpretation of the information and what needs to be done to arrive at a solution. The problem would be ill-structured however, if you disagree on the interpretation of the information, the goals, what the next steps would be and even the constraints.

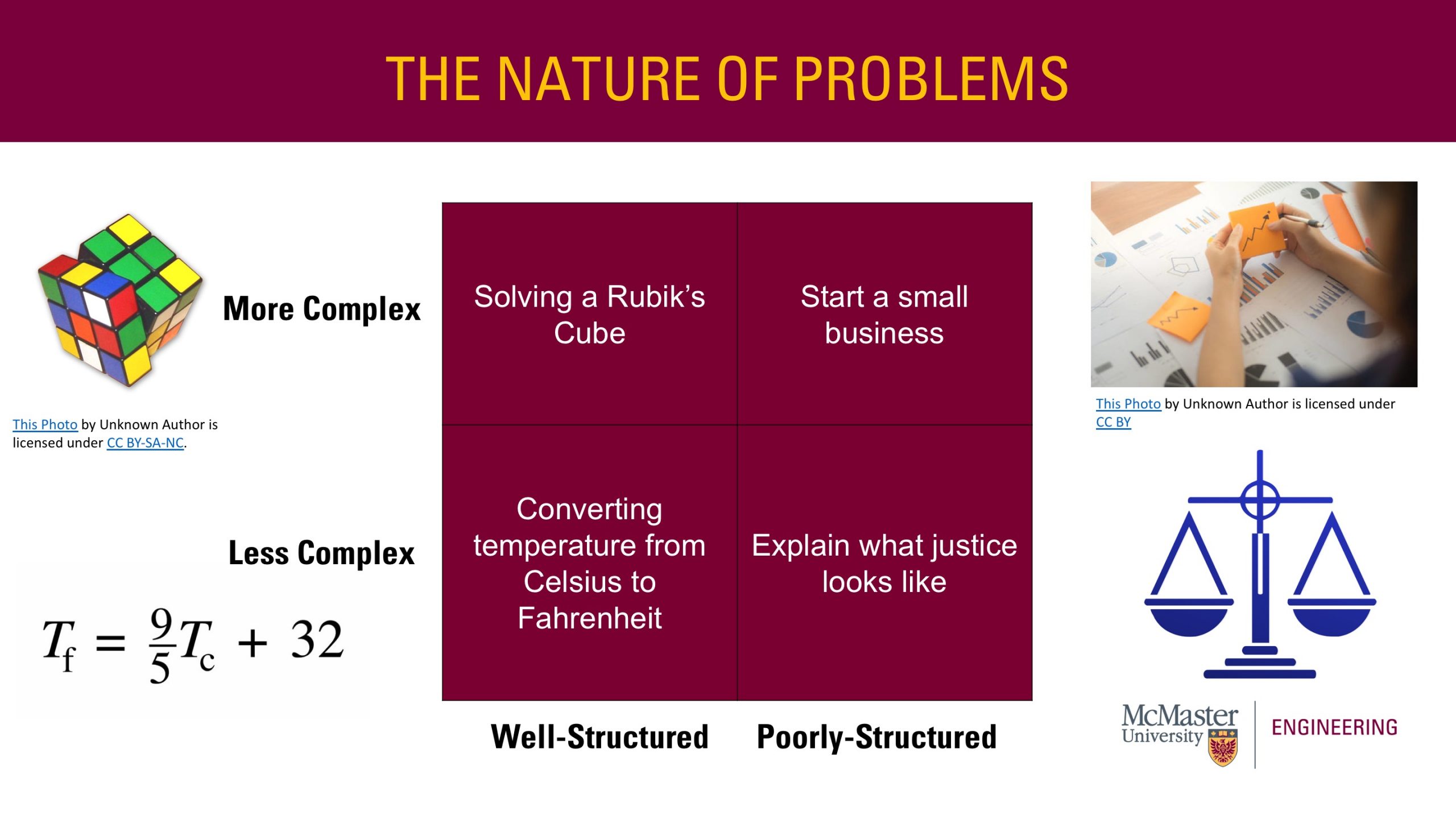

Let’s dive into some examples.

An example of a well-structured and less complex problem would be simply converting temperature from Celsius to Fahrenheit. It is less complex because there only one unknown variable, Fahrenheit, and it is well-structured because the process to convert degrees Celsius to Fahrenheit is a known equation.

Moving up, a well-structured but more complex problem is solving a Rubiks cube. It’s structured because you can all agree on what the objective of the game is, but what makes it complex is that you cant change any single tile without changing at least seven others.

Moving down to the right, a poorly structured but less complex problem is attempting to explain what justice looks like. What makes this less complex is that it’s only referring to one variable, and that is Justice. But, to now explain what Justice looks like, depending on your background, values, morals, justice can look very different. You could probably go in the dictionary to DEFINE justice, but to explain what it LOOKS like can be a downright contentious topic to discuss, making it a very ill-structured problem in that there may very well be differing ideas of the how to arrive at an ‘answer’ and even what the ‘answer’ would be.

Finally, the hardest challenge here, is starting a small business. What makes this a very complex problem is that there are so many variables involved to do so. From financing, base location, logistics, to marketing, and more. And what makes this a poorly-structured challenge is that there is no hard and fast rule to starting a new business. Typically with starting a business there is no ‘right way’ to do so, just a better or a worse way to do.

By now, I hope these examples have helped break down the nature of problems as it relates to complexity and structure.

So now what? Why are we seeking to understand this?

Traditional coursework in university or in higher education in general tend to fall within the less complex and well-structured domain. This means that the problems you are typically exposed to have a right or wrong answer, or right or wrong process.

Sometimes, especially in your final years, you may delve into more complex problems OR poorly structure problems, but almost never both at the same time, unless you are in graduate or final year thesis or capstone projects.

Well, real-world problems, or MacChangers challenges, sit in the poorly-structured and more complex domain. And in fact, this where we operate post graduation and in the professional world. Almost everything we do in the professional world is poorly structured and very complex. The reality is, there are no formulas to real-world problems.

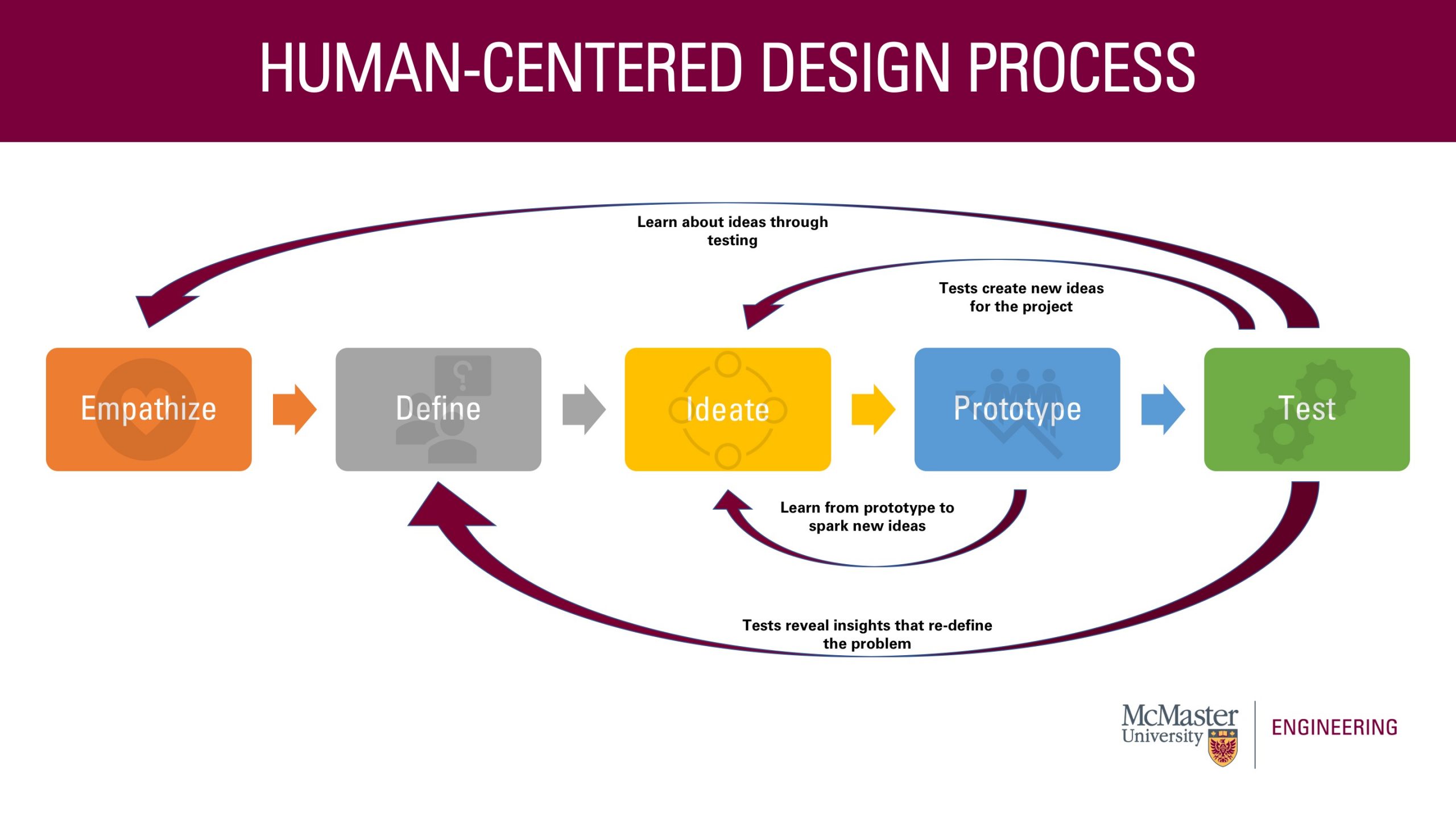

We can start with a human-centered approach. Human centered design is a creative approach to complex and ill-structured problem solving. It’s a process that starts with empathizing with the people experiencing the problem and ends with new solutions that are tailor made to suit their needs. Instead of looking at the technological feasibility or the financial viability of a possible solution, we start with the people who have a vested interest in solving this problem, who we will refer to as stakeholders.

Throughout this entire process, as in the name ‘Human Centered’ makes explicit, it is important to remember that there is a human behind every challenge and so empathy with the user is the guiding strategy to developing meaningful solutions.

Let’s take a look at a real-world example.

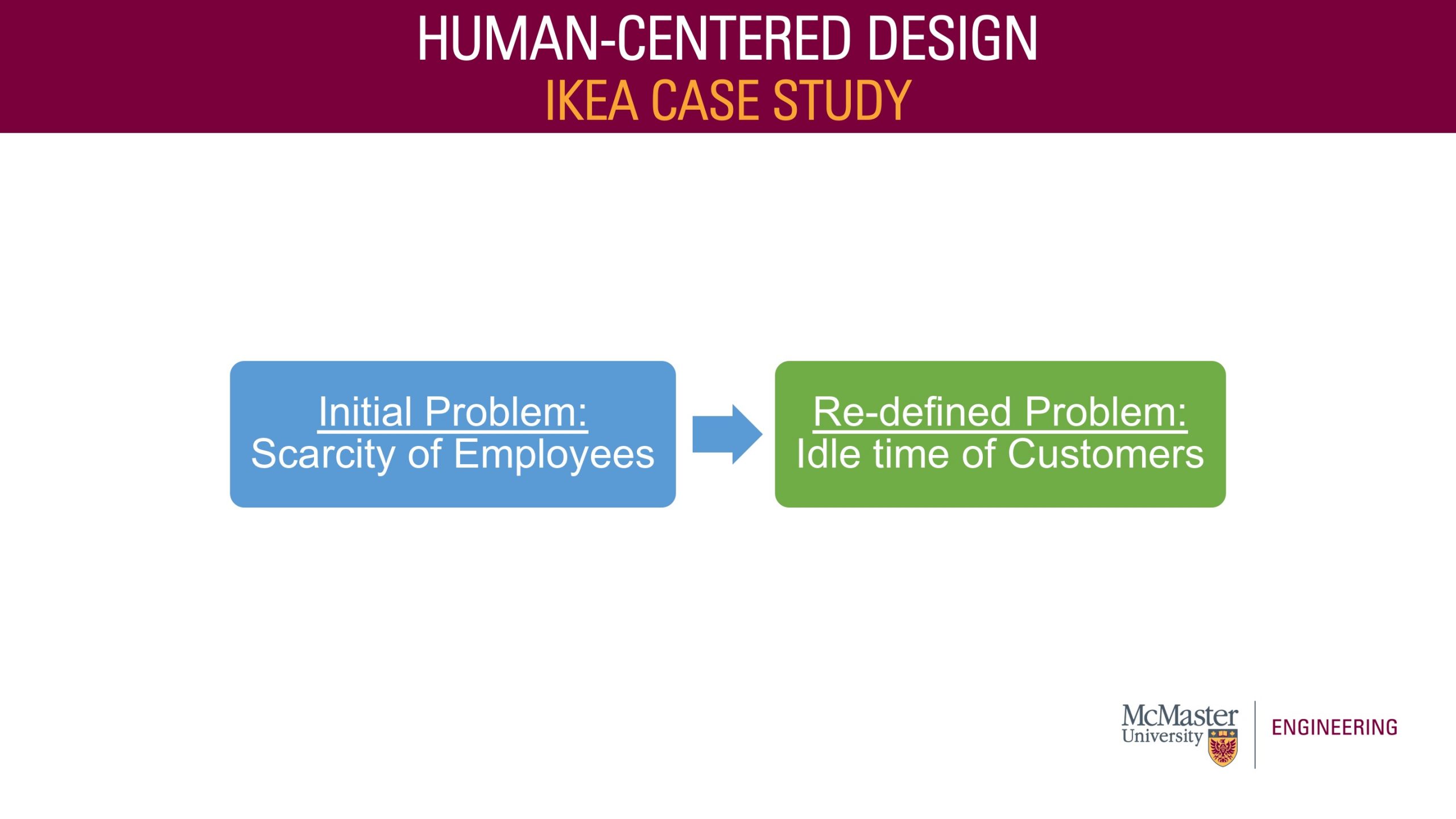

A few years back, IKEA was facing a problem with the shortage of manpower for their stores. Being a low-cost furniture manufacturer, they had their own limitations. Customers were frustrated, waiting to get ordered furniture from the warehouse. So this is a typical employee shortage of employees, shortage of manpower and trying to service the requests and the demands from the consumer.

Being a low cost furniture manufacturer, they had their own limitations. Customers were frustrated, waiting to get ordered furniture from the warehouse. So this is a typical employee shortage of employees, shortage of manpower and trying to service the requests and the demands from the consumer.

Let’s take a look at the two stakeholders in this situation.

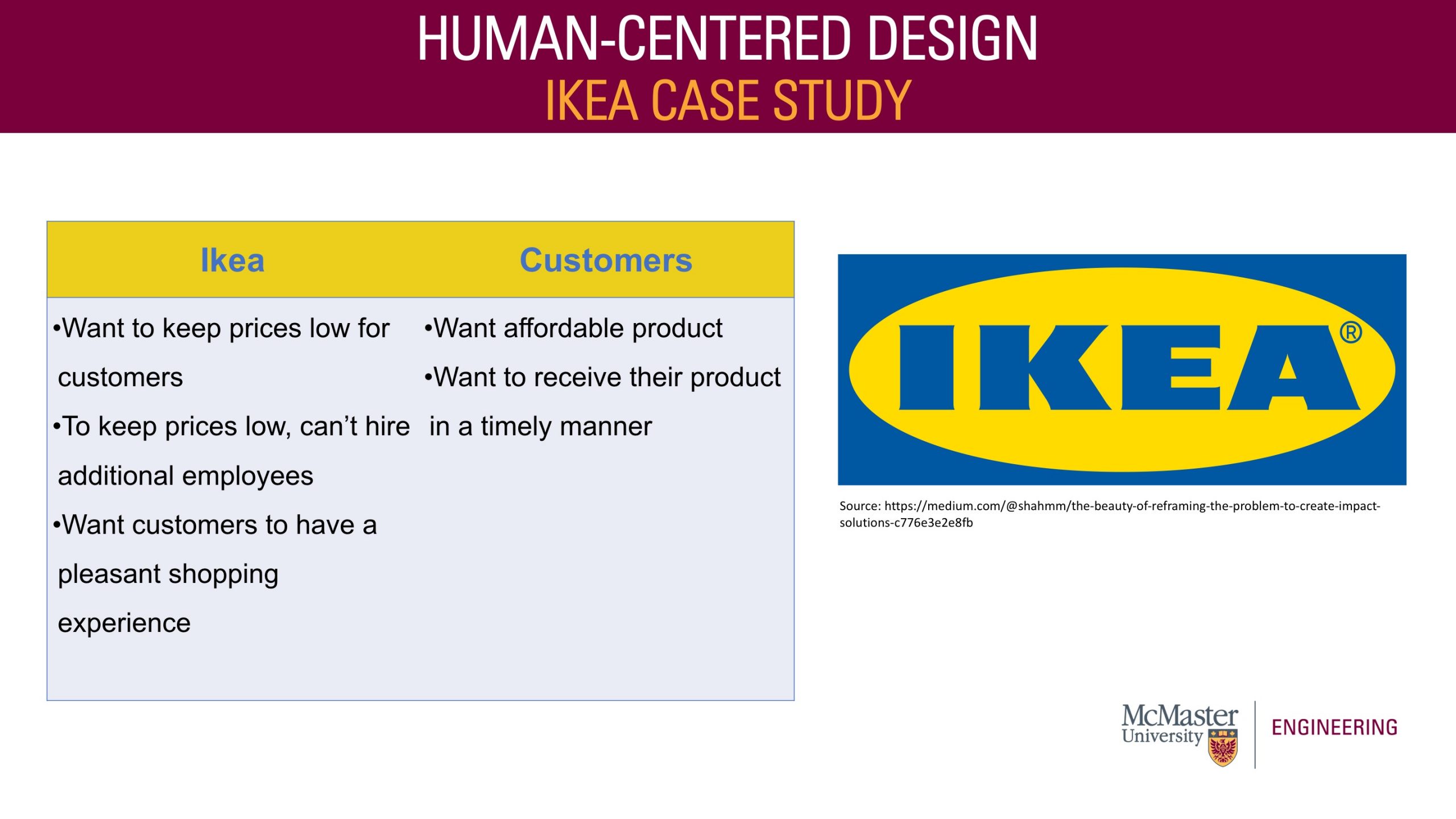

The first stakeholder we’ll talk about is IKEA themselves. IKEA is very interested in keeping prices low for customers to improve customer satisfaction. However, to keep prices low, they can’t hire additional employees because in order to pay them, you need to charge more for your product. Finally, IKEA would like customers to have a pleasant shopping experience because that will increase the chances of them coming back.

From the customer perspective, customers want an affordable product, and they want to receive their product in a timely manner. If you were to solve this problem on pen and paper, your instinct might be for IKEA to hire more employees. But as was just mentioned, hiring more employees means that you need to charge more for your product and charging more for your product likely means that you will start to lose customers somewhere along the way. When working with stakeholders and when working with actual real people as opposed to pen and paper. It’s these kind of ripple effects that you’ll need to keep in mind as you design your solution. So what did IKEA do?

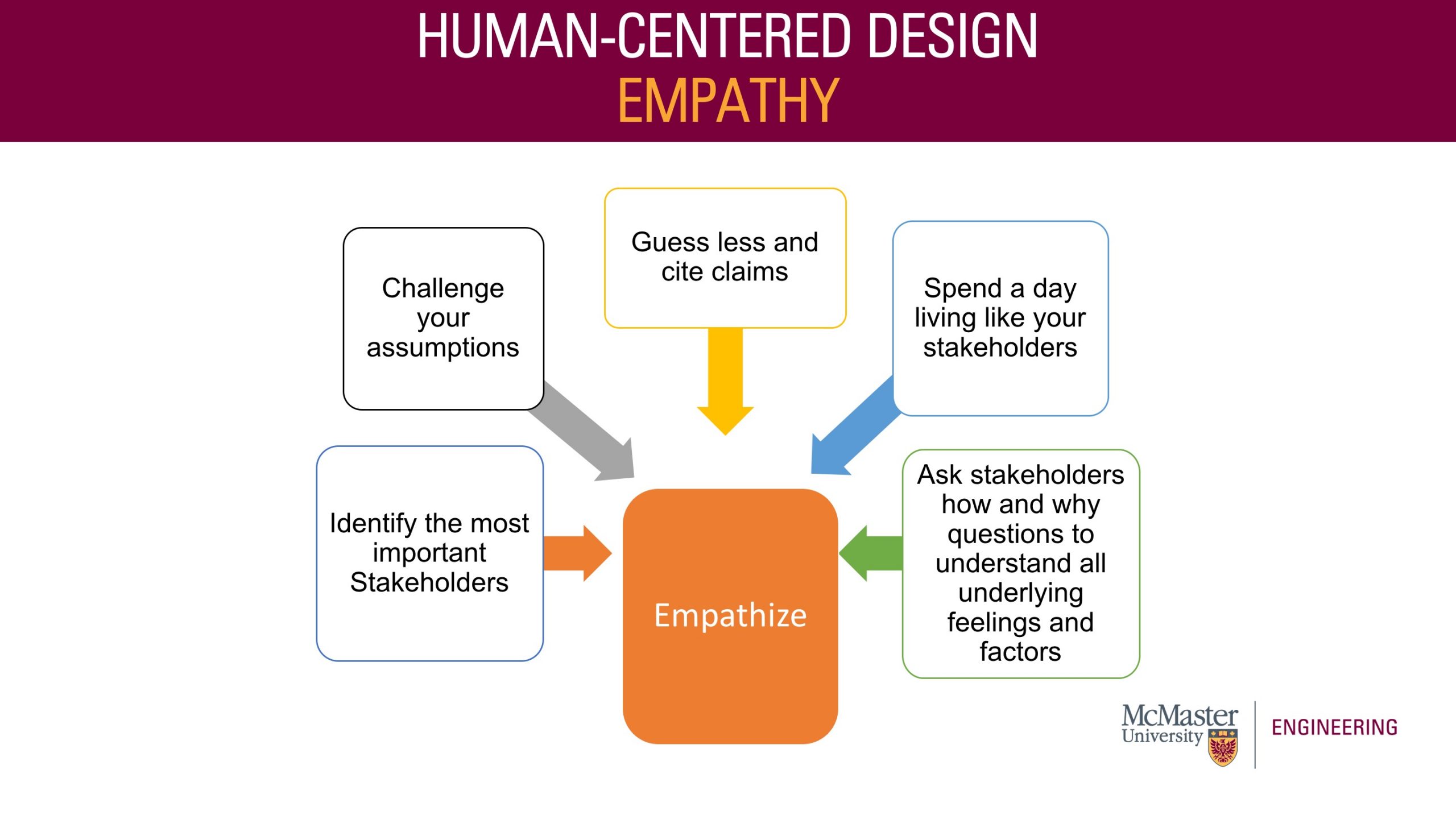

So let’s break down the first stage, empathize. How do we empathize and with who?

We start with the people who have a vested interest in solving this problem, who we will refer to as stakeholders moving forward. When considering stakeholders, there actually tend to be many more than we initially think. It’s best to begin with the interests of and the barriers faced by the three most relevant groups of stakeholders in order to better understand this.

Another way to empathize with stakeholders is to spend a day living like your stakeholder. There is no better way than to put yourself in the shoes of others. If your challenge is to reduce the impact of heat related illnesses in our urban core, take a walk in the city for more than hour on a hot, sunny weekend. Look around you, what does the built environment look like? What kinds of people are out and about? How are people mostly travelling? Are they walking, biking, cycling etc? How do you feel? Are you thirsty or uncomfortable? Imagine if you experienced precarious housing. How would you navigate yourself or where would you flock to?

References

Da Silva, T.,Filipe Pereira, & Marques, J. P. C. (2020). Human-centered design for collaborative innovation in knowledge-based economies. Technology Innovation Management Review, 10(9), 5-15. Retrieved from http://libaccess.mcmaster.ca/login?url=https://www.proquest.com/scholarly-journals/human-centered-design-collaborative-innovation/docview/2450654229/se-2

Nandan, M., Jaskyte, K., & Mandayam, G. (2020). Human Centered Design as a New Approach to Creative Problem Solving: Its Usefulness and Applicability for Social Work Practice. Human Service Organizations: Management, Leadership & Governance, 44(4), 310–316. https://doi.org/10.1080/23303131.2020.1737294

Translated Resources — Stanford d.school. (2022). Retrieved 27 February 2022, from https://dschool.stanford.edu/resources/the-gift-giving-project