35 Upper Arm Musculature

Upper Limb:

Before we discuss the upper limb, let’s clear up a common confusion: the arm and the forearm are not the same thing! Think of the arm as the whole upper limb from shoulder to elbow, while the forearm starts at your elbow and ends at your wrist. This distinction is important, especially when we start talking about muscle actions and their innervations. We’ll use a cooking scenario to explore the interaction of bone, muscle, and joints of the upper limb.

Pectoral Region:

The pectoral region is the anterior side of the chest wall that connects the chest to the arm. The muscles in the pectoral region, given their proximity to the medial side of the arm, will be involved in adduction (moving the arm towards the body) and internal rotation (rotating the arm inwards). Imagine yourself in the kitchen, getting ready to prepare your favourite meal for dinner. Standing at the counter, you reach to your side, adducting these muscles to pull a cutting board towards you.

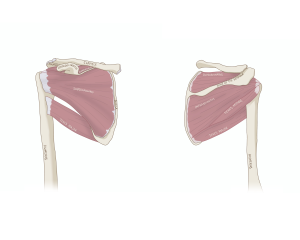

The Shoulder:

The muscles around the shoulder, given their placement on the joint, contribute to arm movements such as abduction (lifting the arm away from the body), flexion and extension (moving the arm forward and backward), and rotation (turning the arm inward or outward). Some shoulder muscles also play a key role in stabilizing the shoulder joint (such as the rotator cuff muscles), ensuring smooth and controlled movement. Certain posterior muscles further support circumduction, allowing for steadier circular arm motions.

Figure 76 Rotator cuff muscles; anterior(left), posterior(right)

Opening and closing the fridge door to take out ingredients requires flexion and extension of the arm. If your recipe requires something from the freezer, you might reach up for the freezer door by abducting the arm. Internal and external rotation of the arm allows you to put your vegetables on the chopping board for cutting and then push them off to one side.

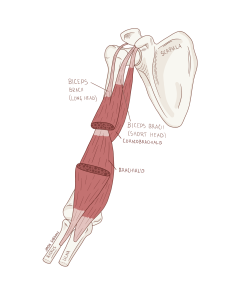

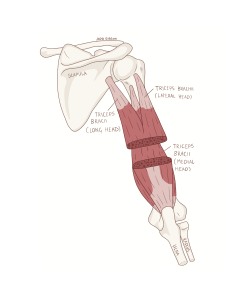

The Arm:

Most of the muscles in the arm travel distally (downward) along the upper limb to attach to the forearm bones, mainly the radius and ulna. In doing so, these muscles will act on the elbow joint. The arm muscles can be grouped into anterior and posterior compartments:

- Anterior Compartment: The muscles in the front of the arm (like the biceps brachii) are responsible for flexion of the elbow. When these muscles contract, they bend the arm at the elbow, bringing the hand closer to the shoulder.

- Posterior Compartment: The muscles like the triceps brachii are responsible for extension, straightening the arm by contracting and pulling the forearm away from the upper arm.

Figure 77 Muscles of the anterior compartment of the arm

Figure 78 Muscles of the posterior compartment of the arm

These muscles work in tandem, as antagonistic pairs, allowing you to raise a spoon to your mouth to taste for seasoning, and then to put the spoon back down through flexion and extension.

The Forearm:

The muscles of the forearm allow for more precise movements, from gripping to fine motor control like typing on a keyboard. Forearm muscles that end in the hand will be responsible for movements of the wrist, whereas those that cross the fingers will contribute to various finger motions. These muscles are categorized based on their location:

- Anterior Compartment: Muscles in the anterior compartment are responsible for flexion at the wrist and fingers. These muscles help bend the wrist (such as flexor carpi radialis and flexor carpi ulnaris) and curl the fingers into a fist (such as flexor digitorum superficialis and flexor digitorum profundus), allowing for grip and manipulation.

- Posterior compartment: Muscles such as the extensor digitorum allow for extension of the wrist and fingers. When these muscles contract, they straighten the wrist and fingers, enabling hand release and other actions.

Perhaps your recipe calls for a canned item. Gripping the can opener involves flexion of the muscles of the anterior compartment and relaxation of muscles of the posterior compartment. Once the lid comes off, the contraction of muscles of the posterior compartment allow you to release your grip on the can opener. You’ll notice that most muscles in the anterior and posterior compartments are involved in flexion and extension, but movement isn’t just strictly limited to forward and backward motions. Some muscles along the sides of the forearm help with side-to-side wrist movements, such as the flexor carpi ulnaris and extensor carpi ulnaris, which pull the wrist toward the pinky side, also known as wrist adduction. You’ll also find muscles that don’t control the wrist or fingers at all, but instead enable forearm rotation. Try turning your palm up and down. That’s the work of the pronator teres and supinator, which handle pronation and supination.

These muscles would be useful for any spills on the countertop which require side-to-side wrist movements as you wipe with a rag, or while using a spatula to flip something in a frying pan with the help of pronation and supination of the wrist.

The hand:

When your meal is just about ready, a final taste test might have you reaching for a last pinch of salt. If you’re big on presentation and plating, you may also sprinkle some herbs on your plated dish to garnish. These finishing touches are made possible by the precise flexion movements of the thenar and hypothenar muscles.

Beyond the thenar and hypothenar muscles, the hand also contains muscles that control finger movement. Between the metacarpal bones (which reside in the palm of your hand), are in the interosseous muscles, which help spread the fingers apart (abduction) and bring them back together (adduction). Another important group is the lumbricals, which allow you to selectively bend your fingers at the knuckles (metacarpophalangeal joints) while keeping the rest of the fingers extended, a motion you use when holding a flat object like a playing card. These small but powerful muscles work together to give your fingers precise control and dexterity!

Finally, your meal is ready! If you’ve had any experience waiting tables, you may be in the habit of carrying plates on your palm with fingers spread apart, thanks to the abduction of your interosseous muscles. Just before you dig in, you might reach for a napkin, pulling it up from the holder in a swift motion using your lumbricals. And you’re already familiar with all the anatomy of eating from studying the digestive system in Chapter 1, so bon appetit!