7 Pharynx and Esophagus

Pharynx

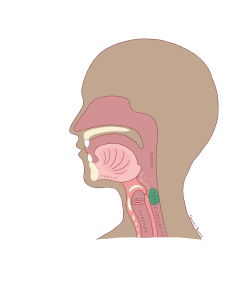

As the bolus leaves the mouth to enter the pharynx, commonly known as the throat. From here the food passes from the oropharynx (the part behind your mouth), then to the laryngopharynx (closer to your voice box) before entering your esophagus. The epiglottis, a small flap acts like a safety guard to make sure food goes into the esophagus and not your trachea.

Figure 7 Sagittal view of pharynx and epiglottis

Tongue: Where foodstuff enters and flows to the pharynx.

Epiglottis: Covers the trachea to allow food to enter the esophagus.

Trachea: Where the respiratory system diverges from the phayrnx.

Esophagus

After leaving the throat, food enters the esophagus—a soft, stretchy tube about 25 cm long. The esophagus passes through an opening in the diaphragm – the muscle which separates the lungs from the abdominal organs – called the esophageal hiatus, on the left side of your body.

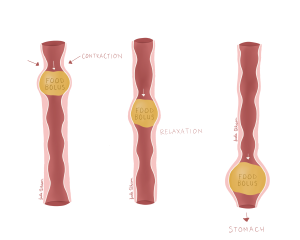

The walls of the esophagus are made of smooth muscle, which allows swallowing to happen involuntarily (without consciously thinking about it). These muscles squeeze in a wave-like motion, called peristalsis, to push food toward your stomach. You can even feel this process if you swallow while upside down—gravity doesn’t stop peristalsis from working!

Figure 8 Peristaltic contractions of esophagus

The esophagus has two key sphincters, acting as the gatekeepers of the digestive system. The upper esophageal sphincter (UES) remains closed and contracted until you swallow, which allows for the bolus to pass through. Muscular contractions known as peristalsis involuntarily propels food further downwards. The lower esophageal sphincter (LES) or cardiac sphincter guards the entrance to the stomach, where it contracts involuntarily to open to allow food into the stomach.

What does the Epiglottis do again?

Hint: The epiglottis serves as a bodyguard to the trachea remaining closed so food doesn’t find its way into the trachea and lungs