37 Hip to thigh musculature

Just like the difference between your arm and forearm, the lower limb can be divided into the thigh (more proximal) and the leg (more distal) – again, these terms are not the same. Try thinking of the thigh as the portion of the lower limb that ranges from the hip to the knee, and the lower leg as the portion ranging from the knee to the foot. These are not just fancy terms, as each region has differing muscle groups, acting on different joints thus producing different actions. To bring this to life, let’s step onto the soccer field. Whether you’re sprinting down the wing, pivoting to defend, or setting up for a shot, the muscles, bones, and joints of your lower limb are working together in a precise, coordinated dance. Throughout this section, we’ll use soccer as our guide to understanding how these body parts interact in real time.

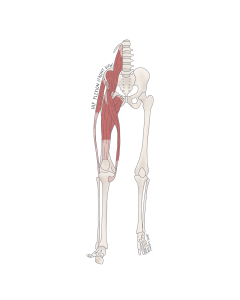

The Anterior Hip Region:

Before the whistle blows, you might find yourself stretching, standing tall and pulling one knee up toward your chest. That motion is powered by a deep-set muscle group known as the iliopsoas, found in the anterior hip region. These muscles anchor to the spine and extend down to the thigh, making them crucial for hip flexion or bringing your thigh toward your torso. Think of it as folding your body like a piece of paper. That hip-to-stomach movement is crucial not only for stretching but also for powering the first lift of your leg as you go to take a step or start a sprint.

The Gluteal Region:

When it’s time to fire off a shot, the muscles in your gluteal region kick into action—literally. While many know the gluteus maximus as the iconic “glute,” it’s only one part of a strong, versatile team. These muscles sit across the posterior and lateral sides of your hips and control key actions like hip extension (swinging the leg backward) and hip abduction (lifting the leg out to the side).

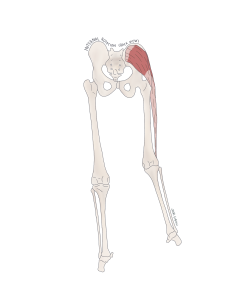

Figure 82 Posterior view of the muscles of the gluteal region internal rotation of the hip

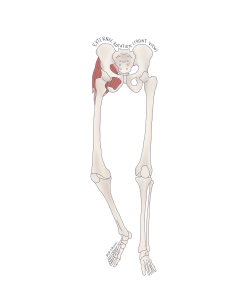

Figure 83 Anterior view of the muscles of the gluteal region executing external rotation of the hip

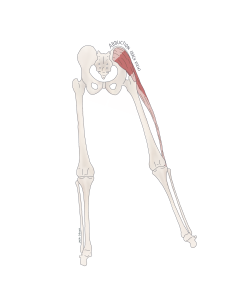

Figure 84 Posterior view of the lateral muscles of the gluteal region executing abduction of the hip

Picture this: you’re winding up for a long-range shot. As your leg sweeps backward, the gluteus maximus contracts, extending your hip. A moment later, if you pivot and pass the ball sideways across your body, smaller gluteal muscles on the side of your hip—like the gluteus medius—activate, abducting your leg out to the side. These muscles have differently oriented fibers (some diagonal, some vertical), making them versatile players for both stability and movement.

The Thigh:

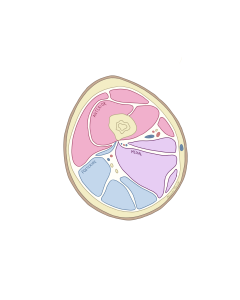

The thigh houses the powerhouse muscle groups that connect the hip to the knee and control motion at both joints. Much like the arm, the thigh is organized into anterior and posterior compartments, two muscle teams working as antagonistic pairs, each performing opposite roles in a coordinated effort. The thigh is also equipped with a medial compartment designed to adduct the thigh towards the midline.

Figure 85 Coronal cross section of the muscular compartments of the thigh (the left thigh – note placement of medial compartment)

- Anterior Compartment: The muscles of the anterior compartment, spanning from the pelvis to the patella (kneecap), are the main drivers of knee extension—like swinging your foot forward to strike a ball. Amongst this anterior group, the sartorius is a unique outlier. It winds down the thigh in an S-shape and wraps around to the back of the knee. Because of this unique path, it takes part in multiple motions, including hip flexion and even leg rotation—perfect for curling the ball into the top corner of the net.

Figure 86 Anterior view of the muscles of the anterior compartment of the thigh

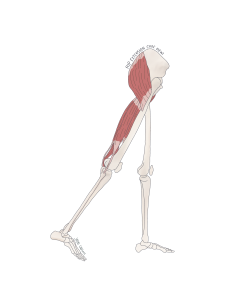

- Posterior Compartment: Muscles commonly referred to as the “hamstrings” compose your posterior compartment and connect the ischial tuberosity (or “sit bones”) of the pelvis to the leg. Contraction of these muscles will cause flexion at the knee joint and even extension at the hip, making them essential for winding up before a kick. One of the key players, the semitendinosus muscle, connects the ischial tuberosity of the hip to the tibia. Therefore, contraction of this muscle will pull the femur (thigh bone) backwards, producing hip extension. Whereas the short head of the biceps femoris, which doesn’t reach the hip, focuses only on knee flexion.

Figure 87 Lateral view of the muscles of the posterior compartment of the thigh producing extension of the hip

-

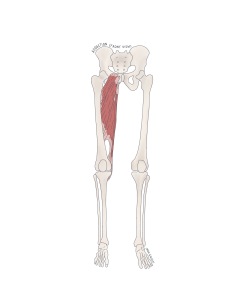

Medial Compartment: The medial compartment of the thigh houses the adductors—muscles responsible for pulling the leg inward, like squeezing a soccer ball between your knees. These muscles originate from the pubis of the pelvis and insert along the femur. One key example is the adductor longus, which runs along the inside of the thigh. When it shortens, it brings the thigh in medially—a motion called adduction. Another key player, the gracilis, is long and strap-like, crossing both the hip and knee joints. Because of its path, it can assist not only in adduction but also in slight flexion of the knee, offering subtle support during movements like crossing your legs or stabilizing your stance on uneven ground.

Figure 88 Anterior view of the muscles of the medial compartment of the thigh

Like the arm, the anterior and posterior compartments of the thigh work together as antagonistic pairs, allowing you to bend your knee to wind up and subsequently extend your leg, producing a single fluid motion. In order to wind up for a kick, your posterior compartment will contract, and thus your anterior compartment must relax as your foot comes behind you before you uncork the winning shot. Whereas to kick a ball sideways across your body as if to pass to your teammate, your medial compartment will produce adduction of the thigh.

The Leg:

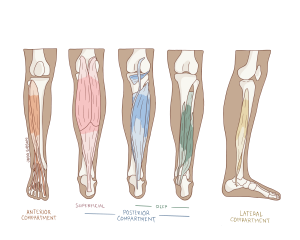

Moving distally from the knee, muscles surround what is commonly referred to as the lower leg, aiding in walking, running, jumping. Yet they also help with more independent movements like standing on your toes (plantarflexion), or bringing the tips of your toes upwards (dorsiflexion). The muscles of the lower leg also aids in eversion (standing on the outside edge of your feet) and inversion (standing on the inside edges of your feet). Compared to the forearm, the lower leg is divided into four compartments, each contributing to movements of the ankle and foot:

Figure 89 Muscular compartments of the leg

- Anterior Compartment: These muscles pull your toes upward, a motion known as dorsiflexion. The star here is the tibialis anterior, which runs down the shin and wraps around to the inside (medial side) of your foot. Imagine you’re stopping mid-dribble to tap the ball with your toe –this motion requires the foot to lift slightly, and that’s the tibialis anterior at work. It also contributes to inversion, tilting the foot so you’re balancing more on its inner edge.

- Lateral Compartment: The muscles of the lateral compartment of the lower leg originate from the fibula and reach under to your sole medial aspect of the foot. Therefore, when these muscles contract, they lift the inner side of your foot, causing you to lean on the outer edge – a movement called eversion. Since the lateral compartment also attaches underneath the foot, when it contracts, it can also lead the foot into plantar flexion (as seen when the sole of the foot is pointed downward, like when a soccer player points their toes to strike the ball with the top of the foot).

- Superficial Posterior Compartment: The posterior compartment can be divided into two layers – superficial and deep. The superficial layer is composed of the classic calf muscles like the gastrocnemius and soleus, which attach to the posterior aspect of your foot via the achilles tendon. When these muscles contract, they can pull the heal up into plantar flexion – like rising onto your toes to make a quick jump or maintaining balance during a penalty kick.

- Deep Posterior Compartment: Hidden beneath the calf are smaller muscles that control finer motions, like toe flexion and adjustments of the ankle. Muscles like the flexor digitorum longus help in curling your toes (flexion). The tibialis posterior, like the calf muscles, assist in plantarflexion and inversion, offering added control when pushing off of uneven ground.

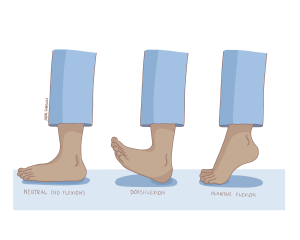

Figure 90 Movements of the foot; neutral (left), dorsiflexion (middle), plantar flexion (right)

The Foot:

At first glance, the foot might seem like the hand’s less glamorous cousin—less dexterous, not built for gripping or fine manipulation. But don’t be fooled: your feet are masters of stability and support, quietly working overtime every time you take a step, sprint, or pivot on the field. Where the hand excels at finesse, the foot is built for endurance. It’s your shock absorber, balance beam, and launch pad—all in one.

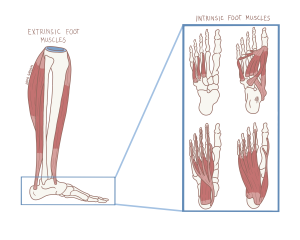

Just as we’ve seen with the lower leg muscles, many of the movements at the ankle and toes—like plantarflexion, dorsiflexion, inversion, and eversion—are powered by extrinsic foot muscles. These muscles live in the lower leg but extend down into the foot. Take the flexor digitorum longus from the deep posterior compartment: though it starts in the leg, it helps curl your toes, offering control as your foot pushes off the ground.

Figure 91 Extrinsic muscles (left) and intrinsic muscles of the foot (right)

Intrinsic Muscles of the Foot:

The intrinsic muscles of the foot are located within the foot. These muscles may be smaller, deeper, and not in control of broad movements, but instead they maintain posture, absorb shock, and fine-tune stability. These are your foot’s local defense squad, working behind the scenes to keep your arches lifted, your toes aligned, and your balance in check.

Picture yourself mid-game, racing across the field and suddenly changing direction. It’s not just your thigh or calf muscles helping you out. Muscles like the adductor hallucis, which tethers your big toe toward the midline of your foot, are hard at work keeping you grounded. Though it seems subtle, this action enhances medial foot stability—especially when one foot is bearing your full body weight during quick turns or landings.

Even though you might not feel them working, these muscles act like internal supports, reinforcing the arches of your foot. Depending on the orientation of their fibers, different intrinsic muscles support different arches. For example, the adductor digiti minimi, which runs along the outer edge of your foot toward your pinky toe, offers lateral stability by supporting the lateral longitudinal arch. Each muscle is like a tension cable in a suspension bridge—its direction and placement determining how it reinforces your foundation.

Deep Foot Muscles:

Beneath the surface are even more specialized layers of muscles, like the plantar and dorsal interossei and lumbricals. Though tiny, these muscles are paramount to flexing the toes at the knuckles and providing stability. You might wonder: What do toes really do anyway? Just try walking barefoot on a balance beam, or sprinting without pushing off from your toes. It’s nearly impossible! These deep muscles don’t just assist with toe movement—they’re instrumental in maintaining your balance. They act like tiny stabilizers that prevent your foot from collapsing or wobbling under pressure. Their positioning also helps uphold the structural integrity of the foot’s arches, reinforcing that spring-like bounce with every step.

Let’s put this all together within the context of our soccer match. When the opening whistle blows, we need to pick up our feet and get running, so we must dorsiflex our feet using our anterior compartment, lifting up our toes from the ground. When running around a tight corner we may need to dig our feet on our outside and inside edges. To dig into your outside edge, your lateral compartment will contract producing eversion. To invert your feet and lean on the inside edges, your anterior compartment will contract. After winning the game, jumping up and embracing your teammates will require your posterior compartment to facilitate plantarflexion so you can lift off the ground. While you may not have noticed, the intrinsic muscles of your feet were busy at work ensuring you were balanced on your feet, supporting the arches below your feet so you could spring into action. Now that the game is finished, put your feet up and relax, but just for a little while – you’ve got anatomy to study!