5 Assessment: helping students develop and demonstrate knowledge and skills

There are many ways for assessment to work in order for learners to build knowledge, track their progress (formative assessment), and to assign grades (summative assessment).

Principles for assessment

The University of Calgary created a thoughtful explanation of five principles for meaningful online assessment, including the why and how to enact the principles, as well as further reading resources. The main points are:

- Focus on learning (especially the most important aims of the course)

- Balance structure with flexibility (consider potential/known challenges students are facing during the pandemic)

- Provide clear instructions and quality, prompt feedback

- When possible, replace timed exams with other types of assessments

- Emphasize academic integrity (e.g., through conversations early and often, and an academic integrity statement in the syllabus)

Asynchronous assessment options

Asynchronous assessment options

There are many options for structuring assessments over the course of the semester. Laurentian University’s CAE Teaching and Innovation team has created this document of samples of alternative assessments. There are many more possibilities of assessments beyond the midterm and final exam that could work with your learning outcomes and course structure that will meet your teaching and learning goals.

- D2L quizzes; posted weekly on, say, Thursdays and due the following Wednesday

- Problem sets, that are not evaluated, but just for learning purposes. Live (or synchronous sessions can review any difficulties students had. Questions and answers can then be posted as PDFs in D2L for self-review.

- Written assignments such as essays and reports, submitted in the dropbox in D2L

Other alternatives include:

- Summarize weekly reading; submitted in the dropbox in D2L

- Collaborative assignments; submit as a D2L assignment

Synchronous assessment options

Synchronous assessment options

- Answer a series of questions in class (via live lecture): the instructor can review and expand on the answers or move on if the concept is well-understood. For example, a poll in Zoom, a Google Form survey or a Menti survey are examples of is a classroom response systems that can be used to gauge students’ understanding of material in near real time—it works as an online version of a clicker. There are many such classroom response systems.

- Submit one or two sentences identifying the main point of a concept using a Google form or in the Zoom chat of a synchronous session.

- Use the polling option in Zoom to gain a sense of students’ understanding or to collect their opinions.

Classroom response systems are popular and useful tools in a virtual classroom. Classroom response systems can be effective from both the learner and teacher perspective and can be used in the following ways:

- Access prior knowledge;

- Confidence-level questions;

- Concept or exam review;

- Question-driven instruction;

- Contingent/agile teaching;

Please note that although there are many great student response tools available, they may be unsupported by Laurentian University. If you choose to use an unsupported technology, Laurentian is unable to support you or your students with any technical difficulties. Please consult the list of Laurentian-supported tech to identify tools that may be suitable in your classroom.

Exams

Exams

A new situation requires new approaches, and one of the most challenging parts of moving to remote teaching is figuring out how to evaluate students’ learning.

A successfully administered midterm or final exam in a remote learning environment will:

- Maintain academic integrity (see policy on Student(see Laurentian University policy on Student academic integrity)

- Permit all students to participate equally;

- Yield a reasonable measurement of student learning;

- Not impose unreasonable costs (monetary or otherwise) for students or the university.

If you wish to give a fairly traditional exam under these non-traditional circumstances, we recommend:

- a collaborative, open-book exam

- an individual, open-book exam

- if open-book exams cannot work, an exam using an online proctoring system such as Respondus Lockdown Browser

To determine what strategy to take, consult the determining your final assessment flowchart.

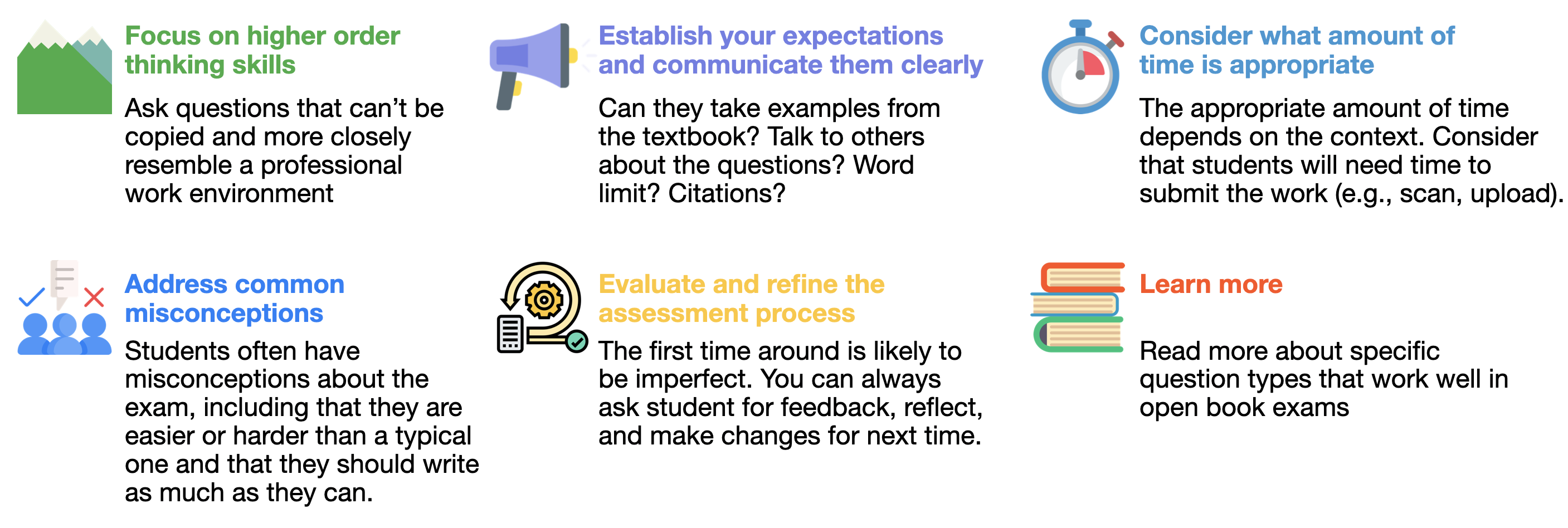

Practical details for open-book exams

Communicate clearly with students about how answers are to be submitted (e.g., there is one submission per group, submit in the D2L dropbox), advise that answers will be checked using plagiarism software (if applicable).

You can require students to certify that they have participated equally in the preparation of answers by asking them to use track changes in word or suggesting features of Google documents.

Traditional exams in a remote teaching world

Traditional exams in a remote teaching world

One of the biggest hurdles to offering a solid, remote learning course is understanding that exams cannot be administered in the traditional way. The practical barriers to assessing students effectively and fairly (and remotely) are significant for most professors. Consider the five principles for meaningful online assessment, explored in detail by the Taylor Institute for Teaching and Learning at the University of Calgary.

In this unique time, we recognize that there are no perfect ways to give a traditional exam under remote learning conditions. It’s harder still during a pandemic. One approach that has occurred too many is to give short, timed exams with the underlying premise that it is harder to cheat if time is very limited. We are skeptical that this is true. Moreover, administering that kind of exam in a remote learning environment is likely to create serious (and stressful) logistical challenges: all it takes is one legitimate technical hurdle and the whole, carefully timed process could fail.

The pandemic makes problems more challenging. We cannot have hundreds of students in gyms writing exams for multiple courses in the morning, followed by a second cohort in the afternoon, and a third in the evening, and expect to maintain physical distancing requirements. For the Fall 2020 and Fall/Winter 2020-21 courses at Laurentian University, no final exams will be held in person during the exam period, as per Senate decision June 1, 2020.

Remotely-administered exam formats require software systems that may be: highly invasive, unreliable or susceptible to academic fraud, too expensive, technologically difficult for students, damaging to students’ experience in our courses, or all of the above. Furthermore, although lockdown browsers and proctoring software may be available, current technology does not overcome the many accessibility, privacy, and implementation challenges that accompany these strategies.

Whatever the exam style, administering the exam will require significant changes relative to typical, in-person exams. It is worth remembering as per this article, that relatively few students cheat on exams.

Most students live up to requirements around academic integrity, although an open book exam is probably going to be collaborative whether you want it to be or not, at least for a few students. Honest students may themselves feel cheated if they know that others have not upheld academic integrity standards and that is also a consideration.

Honour codes can also be used to emphasize and teach students about academic integrity and ethics; students can sign a declaration at the start of their exam attesting that they agree to follow the exam’s guidelines.

Academic integrity

Educators are understandably concerned about academic misconduct and minimizing academic misconduct involves more than putting in measures to stop it. Building a culture of academic integrity involves building trust through conversations and clear communication throughout a course, providing several opportunities for students to demonstrate what they have learned, making efforts to identify academic misconduct (e.g., plagiarized assignments, contract cheating), and institutional support that includes clear and robust policies, integrity campaigns with a positive focus, involving student leaders, and training programs for everyone in the university community.

Some of the essential aspects of academic integrity include:

- Having institutional policies that addresses teaching students about academic integrity and enforcing regulations

- Involving student leaders in conversations and policy-making

- Including explanations about academic integrity in course syllabi

- Class conversations that inform, share expectations, and create an environment of academic integrity

- Requiring that students read and sign an academic integrity statement for the course overall and specific assessments

- Including detailed instruction on assessments indicating what is and is not allowed; don’t assume students will interpret statements the same way you do. For example, saying that an exam is “open book” could mean that the students can consult:

- Only the textbook

- Any source, including the web

- Classmates

- Anyone, anywhere

- Asking questions that require higher order thinking, which make cheating harder

- Designing assessments that mitigate cheating: authentic assessments (e.g., using real data on an assignment that can be used for another/real purpose), multi-stage assessments (individual written then oral), personal reflections

- Deterring academic misconduct, see below

Ways of deterring academic misconduct

- Promoting academic integrity, as described above

- Pros:

- Builds a healthy classroom culture

- Helps students who may not be aware of academic integrity/misconduct

- Cons: some people will always cheat (the same is true in academia with plagiarism)

- Pros:

- Spreading out the weighting of assessments, rather than having a few major ones

- Pros: Addresses major reasons why students engage in academic misconduct

- Cons: Like all methods, not a perfect solution

- Using remote proctoring software

- Pros:

- Deters but does not stop academic misconduct

- May help students feel less pressure to help their friends cheat

- Cons:

- Many students feel this as an invasion of privacy (having to share their home environment)

- Many students find that this type of video proctoring software increases text anxiety, which has had negative impact on performance

- Creates equity issues with students who cannot purchase a webcam or don’t have wifi

- Students can still find ways to cheat (e.g., using bathroom breaks, secondary device)

- Limits in question types that can be asked online; often still need pen/paper

- Risks breaking the trust and community that we are working hard to develop with students—our future honours students, graduate students, colleagues, and co-professionals

- Students with disabilities may get flagged more often than the average student, and as a consequence may feel that their privacy is more violated

- Pros:

- Addressing cases that are identified through institutional academic misconduct policies and processes

- Teach teaching assistants what to do if they suspect cases of academic misconduct

Options for exams that have been used to deter academic misconduct

- Shorter time allowed for exams

- Pros: in principle, harder to get answers in time

- Cons:

- Research shows that this method has little effect

- Forces students in a mode of rapid thinking rather than analytical thinking

- Students can still have others answer for them or search for answers

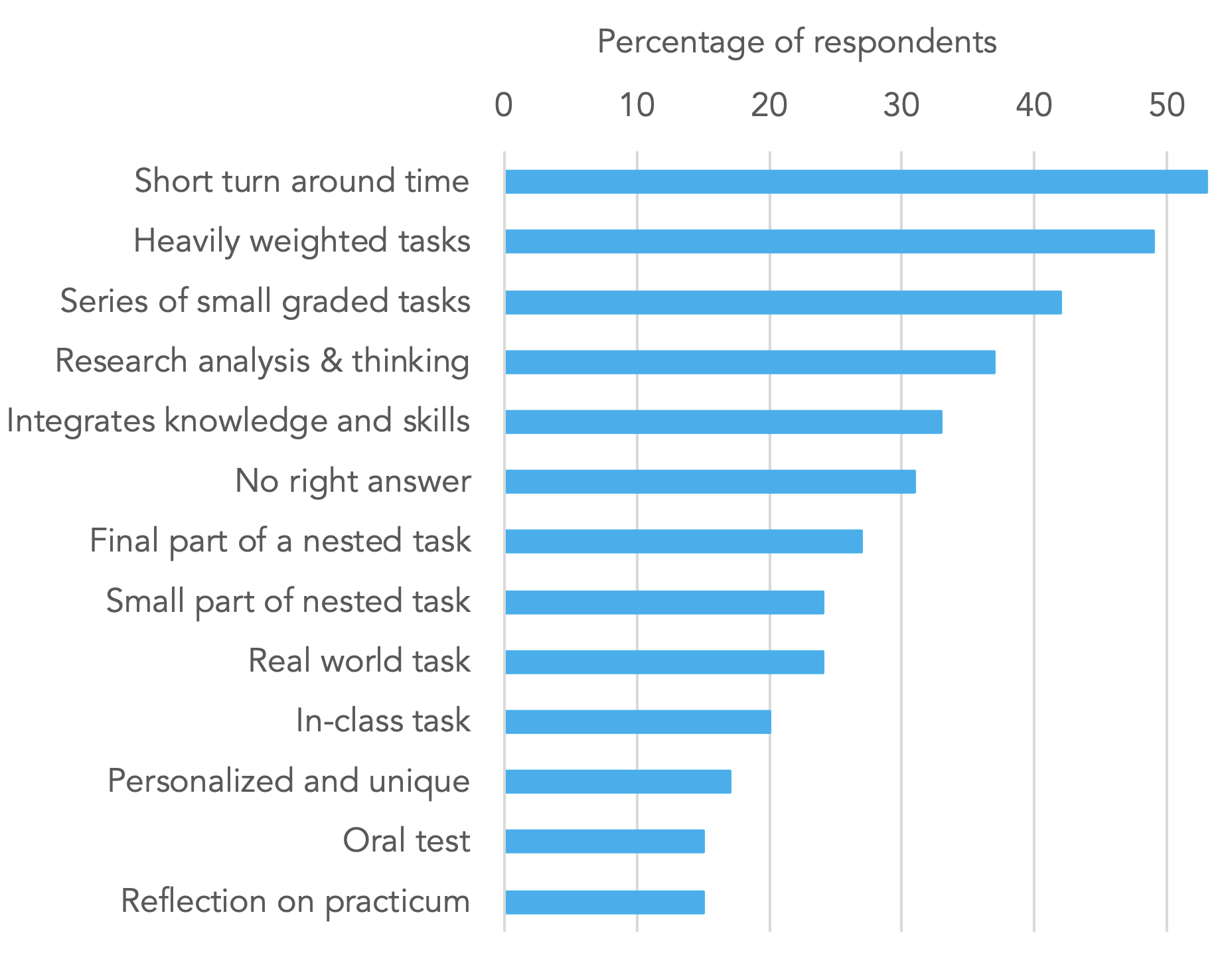

- Students are most likely to cheat on assessments that have a shorter turnaround time or account for a heavily weighted portion of the course grade

- Does not account for technical issues that can arise

- Multiple versions of exams

- Pros: harder to copy from someone else

- Cons: difficult and time-consuming to make many equivalent versions

- Not allowing backtracking (returning to a question once completed)

- Pros:

- Makes it harder for students to submit a question on a website that provides answers while they work on other questions

- Cons:

- Prevents students from working strategically on the exam as they often would (e.g., first answering questions they feel confident doing then leaving others to later)

- Pros:

- Variable question sequences

- Pros: Slightly hinders sharing answers

- Cons: Has relatively little impact

- Allowing students to take the exam only once

- Pros: Analogous to an in-person exam

- Cons:

- Pressure to get the answers right on the first try is a factor in cheating;

- They could do poorly if they have a bad day, are in a distracted home environment.

- Delay score availability

- Pros:

- Indications of correct answers from the professor cannot be shared with others

- Cons:

- Removes an important learning mechanism

- Pros:

- Delay or do not give feedback

- Pros:

- Correct answers from the professor cannot be shared with others

- Cons:

- Removes one of the most important learning mechanisms so substantially and negatively impacts learning and the majority of students in the course (honest students)

- Can build a sense of distrust and harm the course environment

- Pros:

The following graph summarizes the perceptions of cheating on assessments, as reported by those who cheated.

Probability of cheating on assessments, as reported by those who cheated. Chart adapted from Dr. Martin Wielemaker. The data are from Bretag, T., Harper,R., Burton, M., Ellis, C., Newton, P., Van Haeringen, K., Saddiqui, S., and Rozenberg, P. ( 2019). Contract Cheating and Assessment Design: Exploring the Relationship, Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 44(5): 676-691.

Additional readings and resources

- University of Calgary’s Taylor Institute for Teaching and Learning, Five principles for meaningful online assessment

- A Guide for Academics – Open Book Exams

- 5 Tips for Using Take-Home Exams

- Classroom response systems are popular and useful tools in a virtual classroom. Consult the University of Vanderbilt webpage on Classroom Response Systems if you want to learn more on effective practices.

- Create interactive videos using H5P through eCampusOntario’s H5P Studio or other methods, so that students can self-assess as they watch

- Weleschuk, Dyjur, & Kelly. (2019). Online assessment in higher education. Taylor Institute for Teaching and Learning Guide Series

- Wisniewski, Zierer, & Hattie. (2020). The power of feedback revisited: A meta-analysis of educational feedback research. Frontiers of Psychology. 10:3087. DOI: 10.3389/fpsyg.2019.03087

- Jopp & Cohen. (2020) Choose your own assessment – assessment choice for students in online higher education. Teaching in Higher Education, pages 1-18. DOI: 10.1080/13562517.2020.1742680

Up next

The next chapter addresses communication in the course, both between you and students and well as among students themselves.

Please feel free to contact us at any time with questions, suggestions, and concerns by emailing coffeehouse@laurentian.ca

The goal of formative assessment is to monitor student learning to provide ongoing feedback that can be used by instructors to improve their teaching and by students to improve their learning. More specifically, formative assessments:

- help students identify their strengths and weaknesses and target areas that need work

- help faculty recognize where students are struggling and address problems immediately

Formative assessments are generally low stakes, which means that they have low or no point value. Examples of formative assessments include asking students to:

- submit one or two sentences identifying the main point of a lecture

- turn in a research proposal for early feedback

- complete a problem set

Source: https://www.cmu.edu/teaching/assessment/basics/formative-summative.html

The goal of summative assessment is to evaluate student learning at the end of an instructional unit (e.g., module, course) by comparing it against some standard or benchmark.

Summative assessments are often high stakes, which means that they have a high point value. Examples of summative assessments include:

- a midterm or final exam

- a final project

- a paper

- a senior recital

Information from summative assessments can be used formatively when students or faculty use it to guide their efforts and activities in subsequent courses.

Source: https://www.cmu.edu/teaching/assessment/basics/formative-summative.html

Participants access and work on course materials at different times. Examples include email, discussion forums/chats, and assignments.

During synchronous instruction, the professor and students are online at the same time. Synchronous modes can include videoconferencing, discussion boards, etc.

Classroom response systems are a type of software that allow educators or students to create interactive presentations, which students (or other attendees) can answer using a phone, tablet, laptop. These systems had begun as clickers but are now more seamlessly used on devices that people typically carry with them.

These systems can be used for anonymous polling, to gauge students' understanding of concepts in the course, or for other reasons.

H5P (an abbreviation of HTML5 Package) is an open source plugin that gives you the ability to create, share and reuse content like interactive videos, interactive presentations, games, and quizzes to engage learners in your course.