Development during Emerging Adulthood

The theory of emerging adulthood proposes that a new life stage has arisen between adolescence and young adulthood over the past half-century in industrialized countries. Fifty years ago, most young people in these countries had entered stable adult roles in love and work by their late teens or early twenties. Relatively few people pursued education or training beyond secondary school, and, consequently, most young men were full-time workers by the end of their teens. Relatively few women worked in occupations outside the home, and the median marriage age for women in the United States and in most other industrialized countries in 1960 was around 20 (Arnett & Taber, 1994; Douglass, 2005). The median marriage age for men was around 22, and married couples usually had their first child about one year after their wedding day. All told, for most young people half a century ago, their teenage adolescence led quickly and directly to stable adult roles in love and work by their late teens or early twenties. These roles would form the structure of their adult lives for decades to come.

Now, all that has changed. A higher proportion of young people than ever before—about 70% in the United States—pursue education and training beyond secondary school (National Center for Education Statistics, 2012). The early twenties are not a time of entering stable adult work but a time of immense job instability: In the United States, the average number of job changes from ages 20 to 29 is seven. The median age of entering marriage in the United States is now 27 for women and 29 for men (U.S. Bureau of the Census, 2011). Consequently, a new stage of the life span, emerging adulthood, has been created, lasting from the late teens through the mid-twenties, roughly ages 18 to 25.

The Five Features of Emerging Adulthood

Five characteristics distinguish emerging adulthood from other life stages (Arnett, 2004). Emerging adulthood is:

- the age of identity explorations;

- the age of instability;

- the self-focused age;

- the age of feeling in-between; and

- the age of possibilities.

Perhaps the most distinctive characteristic of emerging adulthood is that it is the age of identity explorations. That is, it is an age when people explore various possibilities in love and work as they move toward making enduring choices. Through trying out these different possibilities, they develop a more definite identity, including an understanding of who they are, what their capabilities and limitations are, what their beliefs and values are, and how they fit into the society around them. Erik Erikson (1950), who was the first to develop the idea of identity, proposed that it is mainly an issue in adolescence; but that was more than 50 years ago, and today it is mainly in emerging adulthood that identity explorations take place (Côté, 2006).

The explorations of emerging adulthood also make it the age of instability. As emerging adults explore different possibilities in love and work, their lives are often unstable. A good illustration of this instability is their frequent moves from one residence to another. Rates of residential change in American society are much higher at ages 18 to 29 than at any other period of life (Arnett, 2004). This reflects the explorations going on in emerging adults’ lives. Some move out of their parents’ household for the first time in their late teens to attend a residential college, whereas others move out simply to be independent (Goldscheider & Goldscheider, 1999). They may move again when they drop out of college or when they graduate. They may move to cohabit with a romantic partner and then move out when the relationship ends. Some move to another part of the country or the world to study or work. For nearly half of American emerging adults, residential change includes moving back in with their parents at least once (Goldscheider & Goldscheider, 1999). In some countries, such as in southern Europe, emerging adults remain in their parents’ home rather than move out; nevertheless, they may still experience instability in education, work, and love relationships (Douglass, 2005, 2007).

Emerging adulthood is also a self-focused age. Most American emerging adults move out of their parents’ home at age 18 or 19 and do not marry or have their first child until at least their late twenties (Arnett, 2004). Even in countries where emerging adults remain in their parents’ home through their early twenties, as in southern Europe and in Asian countries such as Japan, they establish a more independent lifestyle than they had as adolescents (Rosenberger, 2007). Emerging adulthood is a time between adolescents’ reliance on parents and adults’ long-term commitments in love and work, and during these years, emerging adults focus on themselves as they develop the knowledge, skills, and self-understanding they will need for adult life. In the course of emerging adulthood, they learn to make independent decisions about everything from what to have for dinner to whether or not to get married.

Another distinctive feature of emerging adulthood is that it is an age of feeling in-between, not adolescent but not fully adult, either. When asked, “Do you feel that you have reached adulthood?” the majority of emerging adults respond neither yes nor no but with the ambiguous “in some ways yes, in some ways no” (Arnett, 2003, 2012). It is only when people reach their late twenties and early thirties that a clear majority feels adult. Most emerging adults have the subjective feeling of being in a transitional period of life, on the way to adulthood but not there yet. This “in-between” feeling in emerging adulthood has been found in a wide range of countries, including Argentina (Facio & Micocci, 2003), Austria (Sirsch, Dreher, Mayr, & Willinger, 2009), Israel (Mayseless & Scharf, 2003), the Czech Republic (Macek, Bejček, & Vaníčková, 2007), and China (Nelson & Chen, 2007).

Finally, emerging adulthood is the age of possibilities, when many different futures remain possible, and when little about a person’s direction in life has been decided for certain. It tends to be an age of high hopes and great expectations, in part because few of their dreams have been tested in the fires of real life. In one national survey of 18- to 24-year-olds in the United States, nearly all—89%—agreed with the statement, “I am confident that one day I will get to where I want to be in life” (Arnett & Schwab, 2012). This optimism in emerging adulthood has been found in other countries as well (Nelson & Chen, 2007).

International Variations

The five features proposed in the theory of emerging adulthood originally were based on research involving about 300 Americans between ages 18 and 29 from various ethnic groups, social classes, and geographical regions (Arnett, 2004). To what extent does the theory of emerging adulthood apply internationally?

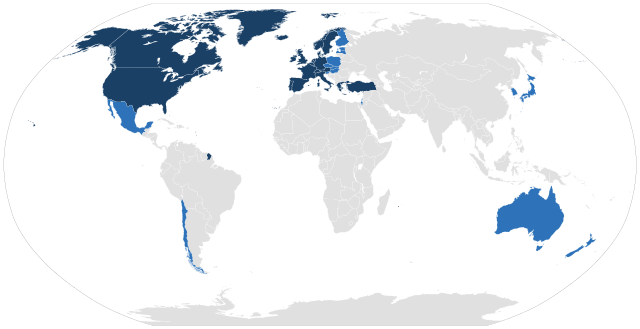

The answer to this question depends greatly on what part of the world is considered. Demographers make a useful distinction between the non-industrialized countries that comprise the majority of the world’s population and the industrialized countries that are part of the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), including the United States, Canada, western Europe, Japan, South Korea, Australia, and New Zealand. The current population of OECD countries (also called industrialized countries) is 1.2 billion, about 18% of the total world population (UNDP, 2011). The rest of the human population resides in non-industrialized countries, which have much lower median incomes; much lower median educational attainment; and much higher incidence of illness, disease, and early death. Let us consider emerging adulthood in OECD countries first, then in non-industrialized countries.

EA in OECD Countries: The Advantages of Affluence

The same demographic changes as described above for the United States have taken place in other OECD countries as well. This is true of participation in postsecondary education as well as median ages for entering marriage and parenthood (UN data, 2010). However, there is also substantial variability in how emerging adulthood is experienced across OECD countries. Europe is the region where emerging adulthood is the longest and most leisurely. The median ages for entering marriage and parenthood are near 30 in most European countries (Douglass, 2007). Europe today is the location of the most affluent, generous, and egalitarian societies in the world—in fact, in human history (Arnett, 2007). Governments pay for tertiary education, assist young people in finding jobs, and provide generous unemployment benefits for those who cannot find work. In northern Europe, many governments also provide housing support. Emerging adults in European societies make the most of these advantages, gradually making their way to adulthood during their twenties while enjoying travel and leisure with friends.

The lives of Asian emerging adults in industrialized countries such as Japan and South Korea are in some ways similar to the lives of emerging adults in Europe and in some ways strikingly different. Like European emerging adults, Asian emerging adults tend to enter marriage and parenthood around age 30 (Arnett, 2011). Like European emerging adults, Asian emerging adults in Japan and South Korea enjoy the benefits of living in affluent societies with generous social welfare systems that provide support for them in making the transition to adulthood—for example, free university education and substantial unemployment benefits.

However, in other ways, the experience of emerging adulthood in Asian OECD countries is markedly different than in Europe. Europe has a long history of individualism, and today’s emerging adults carry that legacy with them in their focus on self-development and leisure during emerging adulthood. In contrast, Asian cultures have a shared cultural history emphasizing collectivism and family obligations. Although Asian cultures have become more individualistic in recent decades as a consequence of globalization, the legacy of collectivism persists in the lives of emerging adults. They pursue identity explorations and self-development during emerging adulthood, like their American and European counterparts, but within narrower boundaries set by their sense of obligations to others, especially their parents (Phinney & Baldelomar, 2011). For example, in their views of the most important criteria for becoming an adult, emerging adults in the United States and Europe consistently rank financial independence among the most important markers of adulthood. In contrast, emerging adults with an Asian cultural background especially emphasize becoming capable of supporting parents financially as among the most important criteria (Arnett, 2003; Nelson, Badger, & Wu, 2004). This sense of family obligation may curtail their identity explorations in emerging adulthood to some extent, as they pay more heed to their parents’ wishes about what they should study, what job they should take, and where they should live than emerging adults do in the West (Rosenberger, 2007).

Another notable contrast between Western and Asian emerging adults is in their sexuality. In the West, premarital sex is normative by the late teens, more than a decade before most people enter marriage. In the United States and Canada, and in northern and eastern Europe, cohabitation is also normative; most people have at least one cohabiting partnership before marriage. In southern Europe, cohabiting is still taboo, but premarital sex is tolerated in emerging adulthood. In contrast, both premarital sex and cohabitation remain rare and forbidden throughout Asia. Even dating is discouraged until the late twenties when it would be a prelude to a serious relationship leading to marriage. In cross-cultural comparisons, about three-fourths of emerging adults in the United States and Europe report having had premarital sexual relations by age 20, versus less than one fifth in Japan and South Korea (Hatfield & Rapson, 2006).

EA in Non-Industrialized Countries: Low But Rising

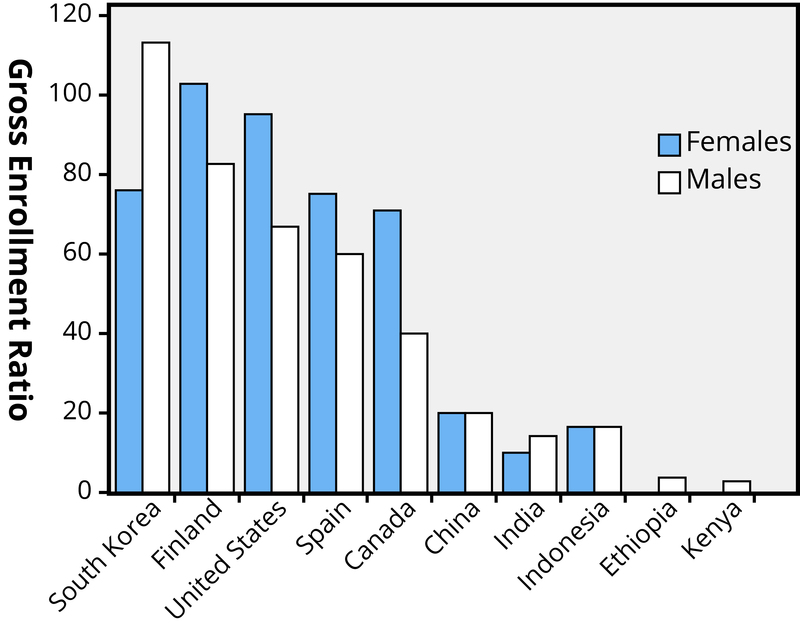

Emerging adulthood is well established as a normative life stage in the industrialized countries described thus far, but it is still growing in non-industrialized countries. Demographically, in non-industrialized countries as in OECD countries, the median ages for entering marriage and parenthood have been rising in recent decades, and an increasing proportion of young people have obtained post-secondary education. Nevertheless, currently, it is only a minority of young people in non-industrialized countries who experience anything resembling emerging adulthood. The majority of the population still marries around age 20 and has long finished education by the late teens. As you can see in Figure 1, rates of enrollment in tertiary education are much lower in non-industrialized countries (represented by the five countries on the right) than in OECD countries (represented by the five countries on the left).

For young people in non-industrialized countries, emerging adulthood exists only for the wealthier segment of society, mainly the urban middle class, whereas the rural and urban poor—the majority of the population—have no emerging adulthood and may even have no adolescence because they enter adult-like work at an early age and also begin marriage and parenthood relatively early. What Saraswathi and Larson (2002) observed about adolescence applies to emerging adulthood as well: “In many ways, the lives of middle-class youth in India, South East Asia, and Europe have more in common with each other than they do with those of poor youth in their own countries.” However, as globalization proceeds, and economic development along with it, the proportion of young people who experience emerging adulthood will increase as the middle class expands. By the end of the 21st century, emerging adulthood is likely to be normative worldwide.

Education and Work

Education in Early Adulthood

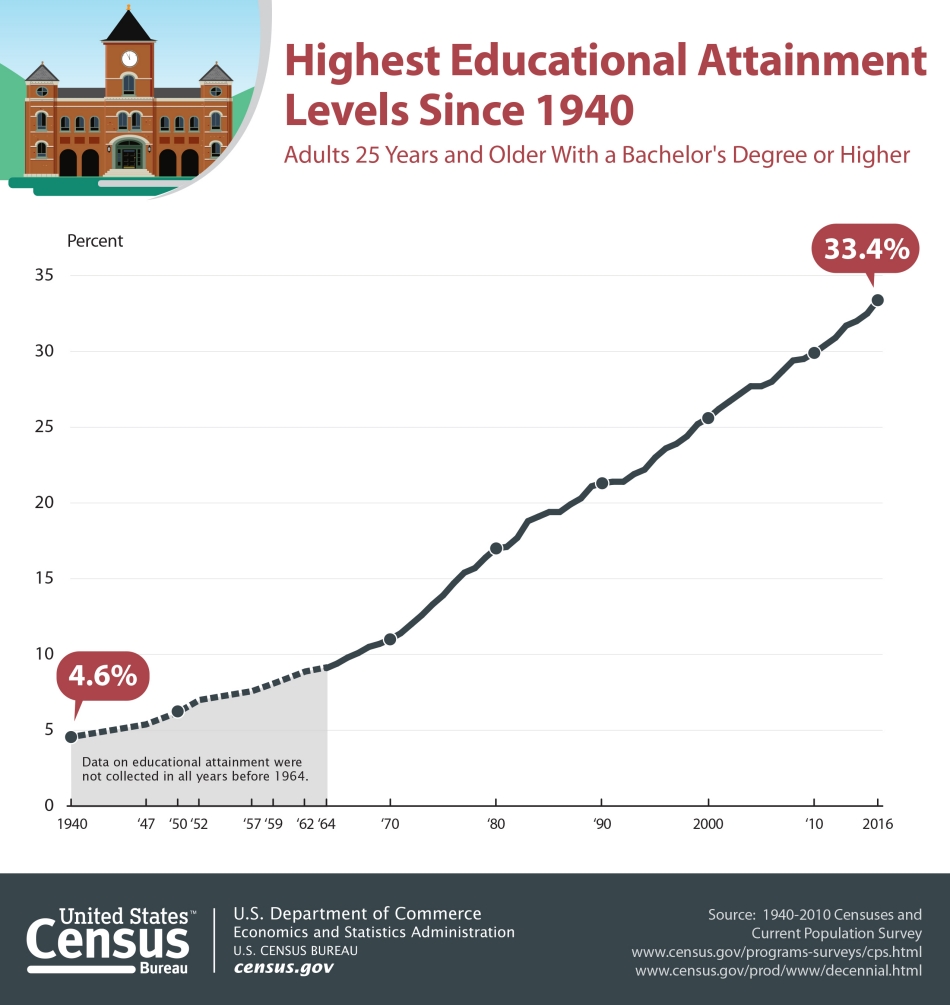

According to the U.S. Census Bureau (2017), 90 percent of the American population 25 and older have completed high school or higher level of education—compare this to just 24 percent in 1940! Each generation tends to earn (and perhaps need) increased levels of formal education. As we can see in the graph, approximately one-third of the American adult population has a bachelor’s degree or higher, as compared with less than 5 percent in 1940. Educational attainment rates vary by gender and race. In all races combined, women are slightly more likely to have graduated from college than men; that gap widens with graduate and professional degrees. However, wide racial disparities still exist. For example, 23 percent of African-Americans have a college degree and only 16.4 percent of Hispanic Americans have a college degree, compared to 37 percent of non-Hispanic white Americans. The college graduation rates of African-Americans and Hispanic Americans have been growing in recent years, however (the rate has doubled since 1991 for African-Americans and it has increased 60 percent in the last two decades for Hispanic-Americans).

Education and the Workplace

With the rising costs of higher education, various news headlines have asked if a college education is worth the cost. One way to address this question is in terms of the earning potential associated with various levels of educational achievement. In 2016, the average earnings for Americans 25 and older with only a high school education was $35,615, compared with $65,482 for those with a bachelor’s degree, compared with $92,525 for those with more advanced degrees. Average earnings vary by gender, race, and geographical location in the United States.

Of concern in recent years is the relationship between higher education and the workplace. In 2005, American educator and then Harvard University President, Derek Bok, called for a closer alignment between the goals of educators and the demands of the economy. Companies outsource much of their work, not only to save costs but to find workers with the skills they need. What is required to do well in today’s economy? Colleges and universities, he argued, need to promote global awareness, critical thinking skills, the ability to communicate, moral reasoning, and responsibility in their students. Regional accrediting agencies and state organizations provide similar guidelines for educators. Workers need skills in listening, reading, writing, speaking, global awareness, critical thinking, civility, and computer literacy—all skills that enhance success in the workplace.

More than a decade later, the question remains: does formal education prepare young adults for the workplace? It depends on whom you ask. In an article referring to information from the National Association of Colleges and Employers’ 2018 Job Outlook Survey, Bauer-Wolf (2018) explains that employers perceive gaps in students’ competencies but many graduating college seniors are overly confident. The biggest difference was in perceived professionalism and work ethic (only 43 percent of employers thought that students are competent in this area compared to 90 percent of the students). Similar differences were also found in terms of oral communication, written communication, and critical thinking skills. Only in terms of digital technology skills were more employers confident about students’ competencies than were the students (66 percent compared to 60 percent).

It appears that students need to learn what some call “soft skills,” as well as the particular knowledge and skills within their college major. As education researcher Loni Bordoloi Pazich (2018) noted, most American college students today are enrolling in business or other pre-professional programs and to be effective and successful workers and leaders, they would benefit from the communication, teamwork, and critical thinking skills, as well as the content knowledge, gained from liberal arts education. In fact, two-thirds of children starting primary school now will be employed in jobs in the future that currently do not exist. Therefore, students cannot learn every single skill or fact that they may need to know, but they can learn how to learn, think, research, and communicate well so that they are prepared to continually learn new things and adapt effectively in their careers and lives since the economy, technology, and global markets will continue to evolve.

An important consideration in managing employees is age. Workers’ expectations and attitudes are developed in part by experience in particular cultural time periods. Generational constructs are somewhat arbitrary, yet they may be helpful in setting broad directions to organizational management as one generation leaves the workforce and another enters it. The baby boomer generation (born between 1946 and 1964) is in the process of leaving the workforce and will continue to depart it for a decade or more. Generation X (born between the early 1960s and the 1980s) are now in the middle of their careers. Millennials (born from 1979 to early 1994) began to come of age at the turn of the century, and are early in their careers.

Today, as these three different generations work side by side in the workplace, employers and managers need to be able to identify their unique characteristics. Each generation has distinctive expectations, habits, attitudes, and motivations (Elmore, 2010). One of the major differences among these generations is knowledge of the use of technology in the workplace. Millennials are technologically sophisticated and believe their use of technology sets them apart from other generations. They have also been characterized as self-centered and overly self-confident. Their attitudinal differences have raised concerns for managers about maintaining their motivation as employees and their ability to integrate into organizational culture created by baby boomers (Myers & Sadaghiani, 2010). For example, millennials may expect to hear that they need to pay their dues in their jobs from baby boomers who believe they paid their dues in their time. Yet millennials may resist doing so because they value life outside of work to a greater degree (Myers & Sadaghiani, 2010). Meister & Willyerd (2010) suggest alternative approaches to training and mentoring that will engage millennials and adapt to their need for feedback from supervisors: reverse mentoring, in which a younger employee educates a senior employee in social media or other digital resources. The senior employee then has the opportunity to provide useful guidance within a less demanding role.

Recruiting and retaining millennials and Generation X employees poses challenges that did not exist in previous generations. The concept of building a career with the company is not relatable to most Generation X employees, who do not expect to stay with one employer for their career. This expectation arises from a reduced sense of loyalty because they do not expect their employer to be loyal to them (Gibson, Greenwood, & Murphy, 2009). Retaining Generation X workers thus relies on motivating them by making their work meaningful (Gibson, Greenwood, & Murphy, 2009). Since millennials lack an inherent loyalty to the company, retaining them also requires effort in the form of nurturing through frequent rewards, praise, and feedback.

Millennials are also interested in having many choices, including options in work scheduling, choice of job duties, and so on. They also expect more training and education from their employers. Companies that offer the best benefits package and brand attract millennials (Myers & Sadaghiani, 2010).

Career Choices in Early Adulthood

Hopefully, we are each becoming lifelong learners, particularly since we are living longer and will most likely change jobs multiple times during our lives. However, for many, our job changes will be within the same general occupational field, so our initial career choice is still significant. We’ve seen with Erikson that identity largely involves occupation and, as we will learn in the next section, Levinson found that young adults typically form a dream about work (though females may have to choose to focus relatively more on work or family initially with “split” dreams). The American School Counselor Association recommends that school counselors aid students in their career development beginning as early as kindergarten and continue this development throughout their education.

One of the most well-known theories about career choice is from John Holland (1985), who proposed that there are six personality types (realistic, investigative, artistic, social, enterprising, and conventional), as well as varying types of work environments. The better matched one’s personality is to the workplace characteristics, the more satisfied and successful one is predicted to be with that career or vocational choice. Research support has been mixed and we should note that there is more to satisfaction and success in a career than one’s personality traits or likes and dislikes. For instance, education, training, and abilities need to match the expectations and demands of the job, plus the state of the economy, availability of positions, and salary rates may play practical roles in choices about work.

Link to Learning: What’s Your Right Career?

To complete a free online career questionnaire and identify potential careers based on your preferences, go to Career One Stop Questionnaire

Did you find out anything interesting? Think of this activity as a starting point to your career exploration. Other great ways for young adults to research careers include informational interviewing, job shadowing, volunteering, practicums, and internships. Once you have a few careers in mind that you want to find out more about, go to the Occupational Outlook Handbook from the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics to learn about job tasks, required education, average pay, and projected outlook for the future.

The O*Net database describes the skills, knowledge, and education required for occupations, as well as what personality types and work styles are best suited to the role. See what it has to say about being a food server in a restaurant or an elementary school teacher or an industrial-organizational psychologist to learn more about these career paths.

EVERYDAY CONNECTION: Preparing for the Job Interview

You might be wondering if psychology research can tell you how to succeed in a job interview. As you can imagine, most research is concerned with the employer’s interest in choosing the most appropriate candidate for the job, a goal that makes sense for the candidate too. But suppose you are not the only qualified candidate for the job; is there a way to increase your chances of being hired? A limited amount of research has addressed this question.

As you might expect, nonverbal cues are important in an interview. Liden, Martin, & Parsons (1993) found that lack of eye contact and smiling on the part of the applicant led to lower applicant ratings. Studies of impression management on the part of an applicant have shown that self-promotion behaviors generally have a positive impact on interviewers (Gilmore & Ferris, 1989). Different personality types use different forms of impression management, for example, extroverts use verbal self-promotion, and applicants high in agreeableness use non-verbal methods such as smiling and eye contact. Self-promotion was most consistently related with a positive outcome for the interview, particularly if it was related to the candidate’s person-job fit. However, it is possible to overdo self-promotion with experienced interviewers (Howard & Ferris, 1996). Barrick, Swider & Stewart (2010) examined the effect of first impressions during the rapport-building that typically occurs before an interview begins. They found that initial judgments by interviewers during this period were related to job offers and that the judgments were about the candidate’s competence and not just likability. Levine and Feldman (2002) looked at the influence of several nonverbal behaviors in mock interviews on candidates’ likability and projections of competence. Likability was affected positively by greater smiling behavior. Interestingly, other behaviors affected likability differently depending on the gender of the applicant. Men who displayed higher eye contact were less likable; women were more likable when they made greater eye contact. However, for this study male applicants were interviewed by men and female applicants were interviewed by women. In a study carried out in a real setting, DeGroot & Gooty (2009) found that nonverbal cues affected interviewers’ assessments about candidates. They looked at visual cues, which can often be modified by the candidate, and vocal (nonverbal) cues, which are more difficult to modify. They found that interviewer judgment was positively affected by visual and vocal cues of conscientiousness, visual and vocal cues of openness to experience, and vocal cues of extroversion.

What is the take-home message from the limited research that has been done? Learn to be aware of your behavior during an interview. You can do this by practicing and soliciting feedback from mock interviews. Pay attention to any nonverbal cues you are projecting and work at presenting nonverbal cures that project confidence and positive personality traits. And finally, pay attention to the first impression you are making as it may also have an impact on the interview.

What you’ll learn to do: explain theories and perspectives on psychosocial development in emerging adulthood

From a lifespan developmental perspective, growth and development do not stop in childhood or adolescence; they continue throughout adulthood. In this section, we will build on Erikson’s psychosocial stages, then be introduced to theories about transitions that occur during adulthood. According to Levinson, we alternate between periods of change and periods of stability. More recently, Arnett notes that transitions to adulthood happen at later ages than in the past and he proposes that there is a new stage between adolescence and early adulthood called, “emerging adulthood.” Let’s see what you think.

learning outcomes

- Describe Erikson’s stage of intimacy vs. isolation

- Describe personality in emerging adulthood