Most Common Causes of Death

Life Expectancy

Life expectancy is a statistical measure of the average time an organism is expected to live, based on the year of birth, current age, and other demographic factors including gender. The most commonly used measure of life expectancy is at birth (LEB). There are great variations in life expectancy in different parts of the world, mostly due to differences in public health, medical care, and diet, but also affected by education, economic circumstances, violence, mental health, and sex.

Life Expectancy in the United States

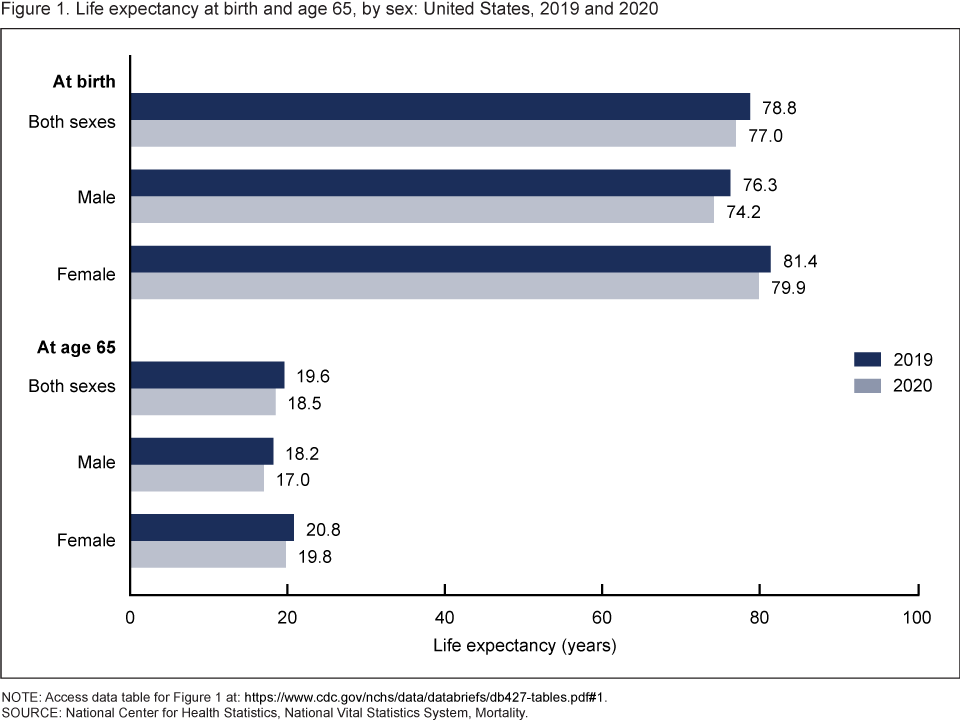

According to the CDC (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention), in 2020, life expectancy at birth was 77.0 years for the total U.S. population—a decrease of 1.8 years from 78.8 years in 2019. For males, life expectancy decreased 2.1 years from 76.3 in 2019 to 74.2 in 2020. For females, life expectancy decreased 1.5 years from 81.4 in 2019 to 79.9 in 2020. In 2020, the difference in life expectancy between females and males was 5.7 years, an increase of 0.6 year from 2019.

In 2020, life expectancy at age 65 for the total population was 18.5 years, a decrease of 1.1 years from 2019. For males, life expectancy at age 65 decreased 1.2 years from 18.2 in 2019 to 17.0 in 2020. For females, life expectancy at age 65 decreased 1.0 year from 20.8 in 2019 to 19.8 in 2020. The difference in life expectancy at age 65 between females and males increased 0.2 year, from 2.6 years in 2019 to 2.8 in 2020.

Statistics from the U.S. Census Bureau reveal that the 85-and over age group is the fastest-growing age group in America. According to the Census Bureau and AgingStats.gov, the over-65 population grew from 3 million in 1900 to 40 million in 2010, an increase of more than 1200%. But during this same time, the over-85 population grew from just over 100,000 in 1900 to 5.5 million in 2010–an increase of 5400%!

Statistics from the U.S. Census Bureau reveal that the 85-and over age group is the fastest-growing age group in America. According to the Census Bureau and AgingStats.gov, the over-65 population grew from 3 million in 1900 to 40 million in 2010, an increase of more than 1200%. But during this same time, the over-85 population grew from just over 100,000 in 1900 to 5.5 million in 2010–an increase of 5400%!

When calculating life expectancy, we consider all of the elements of heredity, health history, current health habits, and current life experiences which contribute to a longer life or subtract from a person’s life expectancy. Recent studies concluded that cutting calorie intake by 15 percent over two years can slow aging and protect against diseases such as cancer, diabetes, and Alzheimer’s (Redman et al., 2018).

Some life factors are beyond a person’s control, and some are controllable. The rising cost of health care is a source of financial vulnerability to older adults. Vaccines are especially important for older adults. As you get older you’re more likely to get diseases like the flu, pneumonia, and shingles, and to have complications that can lead to long-term illness, hospitalization, and even death.

Things that contribute to longer life expectancies include eating a healthy diet that is rich in plants and nuts. Staying physically active, not smoking, and consuming moderate amounts of alcohol, tea, or coffee are also reported to be beneficial to leading a long life. Other recommendations include being conscientious, prioritizing your happiness, avoiding stress and anxiety, and having a strong social support network. Establishing a consistent sleep schedule and maintaining between 7-8 hours of sleep per night is also beneficial (Petre, 2019).

A person will statistically live longer once they reach an older age because they have made it this far without anything killing them. Also, there appear to be several factors that may explain changes in life expectancy in the United States and around the world—health conditions are better, many diseases have been eliminated or better controlled through medicine, working conditions are better and better lifestyle choices are being made. Such factors significantly contribute to longer life expectancies.

Understanding Life Expectancy

Life expectancy is also used in describing the physical quality of life. Quality of life is the general well-being of individuals and societies, outlining negative and positive features of life. Quality of life considers life satisfaction, including everything from physical health, family, education, employment, wealth, safety, security, freedom, religious beliefs, and the environment.

Increased life expectancy brings concern over the health and independence of those living longer. Greater attention is now being given to the number of years a person can expect to live without disability, which is called active life expectancy. When this distinction is made, we see that although women live longer than men, they are more at risk of living with a disability (Weitz, 2007).

What factors contribute to poor health in women? Marriage has been linked to longevity, but spending years in a stressful marriage can increase the risk of illness. This negative effect is experienced more by women than men and seems to accumulate over the years. The impact of a stressful marriage on health may not occur until a woman reaches 70 or older (Umberson et al., 2006). Sexism can also create chronic stress. The stress experienced by women as they work outside the home and care for family members can ultimately negatively impact health (He et al., 2005).

The shorter life expectancy for men in general, is attributed to greater stress, poorer attention to health, more involvement in dangerous occupations, and higher rates of death due to accidents, homicide, and suicide. Social support can increase longevity. For men, life expectancy and health seems to improve with marriage. Spouses are less likely to engage in risky health practices and wives are more likely to monitor their husband’s diet and health regimes. But men who live in stressful marriages can also experience poorer health as a result.

The United States

In 1900, the most common causes of death were infectious diseases, which brought death quickly. Due to advances in healthcare and medicine over the years, this has changed, alongside an increase in average life expectancy. In modern times, chronic diseases, or those in which a slow and steady decline causes health deterioration, are more common. How might this impact the way we think of death, the way we grieve, and the amount of control a person has over his or her own dying process, in comparison to the infectious diseases that were prevalent in 1900?

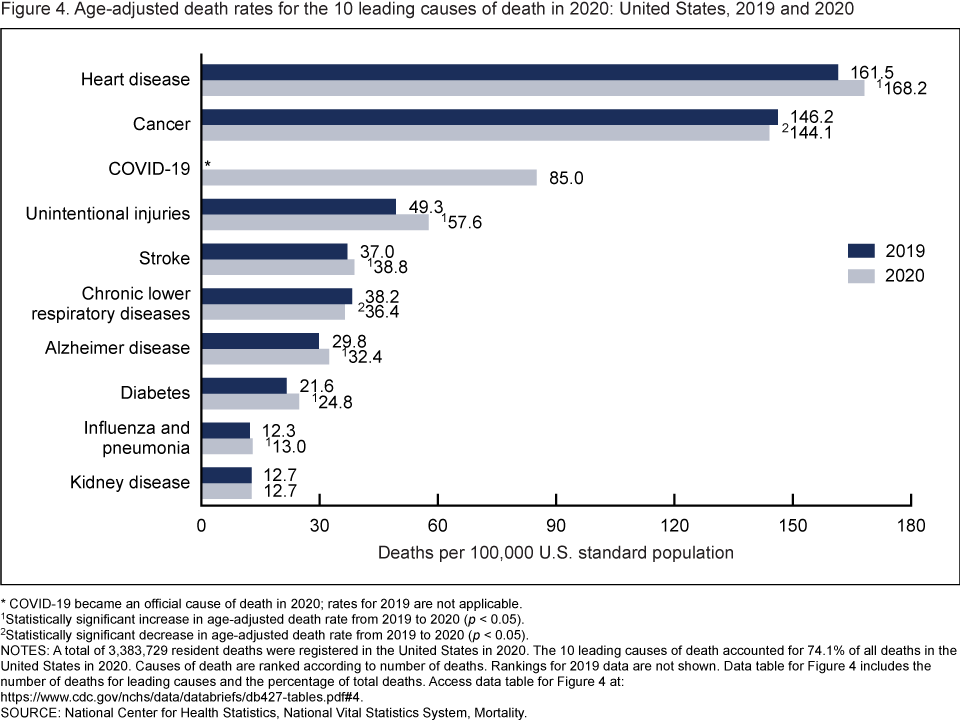

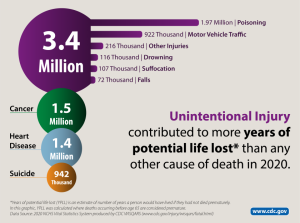

In 2020, 9 of the 10 leading causes of death remained the same as in 2019. The top leading cause was heart disease, followed by cancer. COVID-19, newly added as a cause of death in 2020, became the 3rd leading cause of death. Of the remaining leading causes in 2020 (unintentional injuries, stroke, chronic lower respiratory diseases, Alzheimer disease, diabetes, influenza and pneumonia, and kidney disease), 5 causes changed ranks from 2019. Unintentional injuries, the 3rd leading cause in 2019, became the 4th leading cause in 2020. Chronic lower respiratory diseases, the 4th leading cause in 2019, became the 6th. Alzheimer disease, the 6th leading cause in 2019, became the 7th. Diabetes, the 7th leading cause in 2019, became the 8th. Kidney disease, the 8th leading cause in 2019, became the 10th leading cause in 2020. Stroke, and influenza and pneumonia, remained the 5th and 9th leading causes, respectively (1). Suicide dropped from the list of 10 leading causes in 2020. Causes of death are ranked according to number of deaths (1). The 10 leading causes accounted for 74.1% of all deaths in the United States in 2020.

From 2019 to 2020, age-adjusted death rates increased for 6 of 10 leading causes of death and decreased for 2. The rate increased 4.1% for heart disease (from 161.5 in 2019 to 168.2 in 2020), 16.8% for unintentional injuries (49.3 to 57.6), 4.9% for stroke (37.0 to 38.8), 8.7% for Alzheimer disease (29.8 to 32.4), 14.8% for diabetes (21.6 to 24.8), and 5.7% for influenza and pneumonia (12.3 to 13.0). Rates decreased 1.4% for cancer (146.2 to 144.1) and 4.7% for chronic lower respiratory diseases (38.2 to 36.4). The rate for kidney disease remained unchanged.

Data comparisons from 2019 to 2020 for COVID-19 are not applicable because COVID-19 was a new cause in 2020.

Deadliest Diseases Worldwide

In 2019, the top 10 causes of death accounted for 55% of the 55.4 million deaths worldwide (WHO, 2020). The top global causes of death, in order of the total number of lives lost, are associated with three broad topics: cardiovascular (ischaemic heart disease, stroke), respiratory (chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, lower respiratory infections), and neonatal conditions – which include birth asphyxia and birth trauma, neonatal sepsis and infections, and preterm birth complications.

Causes of death can be grouped into three categories: communicable (infectious and parasitic diseases and maternal, perinatal, and nutritional conditions), noncommunicable (chronic), and injuries. Notice there are several similarities between these and the top 10 causes of death in the United States described above.

Why do we need to know the reasons people die?

It is important to know why people die to improve how people live (WHO, 2020). Measuring how many people die each year helps to assess the effectiveness of our health systems and direct resources to where they are needed most. For example, mortality data can help focus activities and resource allocation among sectors such as transportation, food and agriculture, and the environment as well as health.

COVID-19 has highlighted the importance for countries to invest in civil registration and vital statistics systems to allow daily counting of deaths, and direct prevention and treatment efforts. It has also revealed inherent fragmentation in data collection systems in most low-income countries, where policy-makers still do not know with confidence how many people die and of what causes.

A Comparison of Death by Age in the United States

The major causes of death vary significantly among age groups. As you can see in Figure 1, congenital diseases and accidents are major causes of death among children, then accidents and suicides are the leading causes of death between ages 10 and 24. This changes again and late adulthood, as heart disease and cancer combined cause over 50% of deaths for those aged between 45 and 65. into middle and late adulthood, as heart disease and cancer combined cause over 50% of deaths for those aged between 45 and 65. Notice that unintentional injuries are the leading cause of death for the widest variety of ages. Review the Top 10 Leading Causes of Death by Age Group in 2020

Death and The Media

Interestingly, the things that actually result in death are not often the things we hear about on the news. Because of the availability heuristic—a cognitive shortcut in which people rely heavily on information that is most readily available in their mind, people may erroneously be more afraid of sensational deaths than death by more normal causes, such as heart disease.

The Process of Dying

Aspects of Death

One way to understand death and dying is to look more closely at physiological, social, and psychological death. These deaths do not occur simultaneously, nor do they always occur in a set order. Rather, a person’s physiological, social, and psychological deaths can occur at different times (Butow, 2017).

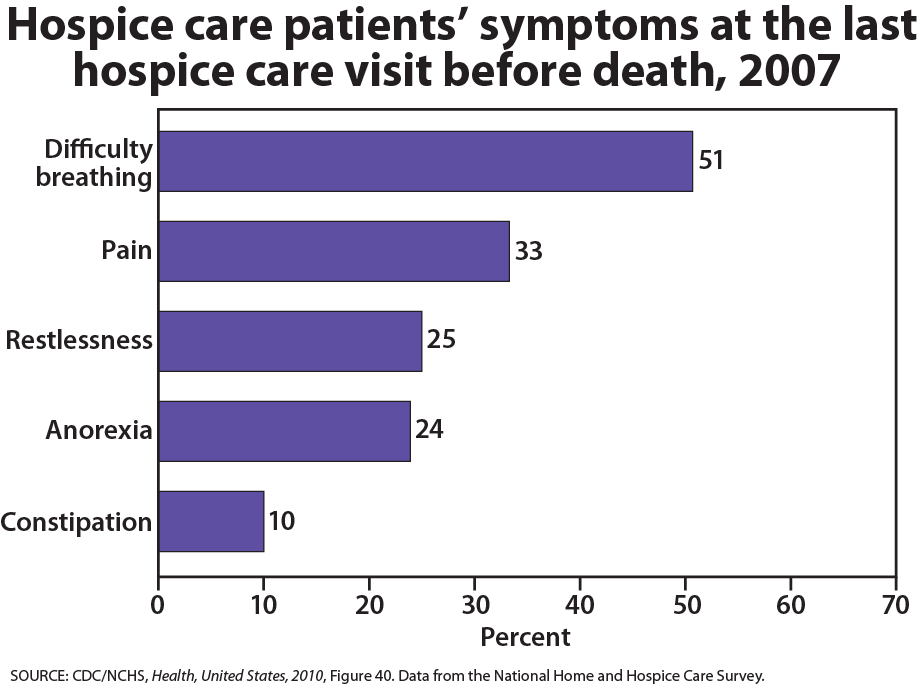

Physiological death occurs when the vital organs no longer function. The digestive and respiratory systems begin to shut down during the gradual process of dying. A dying person no longer wants to eat as digestion slows, the digestive track loses moisture, and chewing, swallowing, and elimination become painful processes. Circulation slows and mottling, or the pooling of blood, may be noticeable on the underside of the body, appearing much like bruising. Breathing becomes more sporadic and shallow and may make a rattling sound as air travels through mucus-filled passageways. Agonal breathing refers to gasping, labored breaths caused by an abnormal pattern of brainstem reflex. The person often sleeps more and more and may talk less, although they may continue to hear. The kinds of symptoms noted prior to death in patients under hospice care (care focused on helping patients die as comfortably as possible) are noted below.

When a person is brain dead or no longer has brain activity, they are clinically dead. Physiological death may take 72 or fewer hours. This is different from a vegetative state, which occurs when the cerebral cortex no longer registers electrical activity but the brain stems continue to be active. Individuals who are kept alive through life support may be classified this way.

Social death begins much earlier than physiological death. Social death occurs when others begin to withdraw from someone who is terminally ill or has been diagnosed with a terminal illness. Those diagnosed with conditions such as AIDS or cancer may find that friends, family members, and even health care professionals begin to say less and visit less frequently. Meaningful discussions may be replaced with comments about the weather or other topics of light conversation. Doctors may spend less time with patients after their prognosis becomes poor. Why do others begin to withdraw? Friends and family members may feel that they do not know what to say or that they can offer no solutions to relieve suffering. They withdraw to protect themselves against feeling inadequate or from having to face the reality of death. Health professionals, trained to heal, may also feel inadequate and uncomfortable facing decline and death. A patient who is dying may be referred to as “circling the drain,” meaning that they are approaching death. People in nursing homes may live as socially dead for years with no one visiting or calling. Social support is important for quality of life and those who experience social death are deprived of the benefits that come from loving interaction with others.

Psychological death occurs when the dying person begins to accept death and to withdraw from others and regress into the self. This can take place long before physiological death (or even social death if others are still supporting and visiting the dying person) and can even bring physiological death closer. People have some control over the timing of their death and can hold on until after important occasions or die quickly after having lost someone important to them. In some cases, individuals can give up their will to live. This is often at least partially attributable to a lost sense of identity. The individual feels consumed by the reality of making final decisions, planning for loved ones—especially children, and coping with the process of his or her own physical death.

Interventions based on the idea of self-empowerment enable patients and families to identify and ultimately achieve their own goals of care, thus producing a sense of empowerment. Self-empowerment for terminally ill individuals has been associated with a perceived ability to manage and control things such as medical actions, changing life roles, and the psychological impacts of the illness (Butow, 2017).

Treatment plans that are able to incorporate a sense of control and autonomy into the dying individual’s daily life have been found to be particularly effective in regards to general attitude as well as depression level. For example, it has been found that when dying individuals are encouraged to recall situations from their lives in which they were active decision-makers, explored various options, and took action, they tend to have better mental health than those who focus on themselves as victims. Similarly, there are several theories of coping that suggest active coping (seeking information, working to solve problems) produces more positive outcomes than passive coping (characterized by avoidance and distraction). Although each situation is unique and depends at least partially on the individual’s developmental stage, the general consensus is that it is important for caregivers to foster a supportive environment and partnership with the dying individual, which promotes a sense of independence, control, and self-respect.

What you’ll learn to do: examine care and practices related to death

In this section, we’ll turn our attention from the process of dying to the actual death of the individual. We’ll examine various ways in which deliberate death can occur, along with the supportive practices that are available for those who are dying. We will also take a closer look at cultural and legal implications of end-of-life practices.

Learning outcomes

- Explain the philosophy and practice of palliative care

- Describe hospice care

- Summarize Dame Cicely Saunders’ writings about total pain of the dying

- Differentiate attitudes toward hospice care based on race and ethnicity

- Describe and contrast types of euthanasia and physician-assisted suicide