Chapter 1: Information Literacy in the Online Environment

Learning Outcomes

- Identify information literacy as an essential skillset for efficient and effective legal research.

- Use specialized vocabulary to describe information-seeking behaviours.

- Identify a range of online search techniques beyond keyword searching.

- Critically assess databases based on their attributes, content, and organization, to determine utility for research.

1.1 Introduction: What is information literacy in legal research?

In this chapter, we introduce information literacy as a core competency for legal practitioners. We discuss aspects of the online research environment that can significantly impact efficiency for an information seeker. These include an understanding of the availability of information online, the distinction between legal research services and databases, fundamental search techniques, and the use of AI in legal-information seeking.

Legal practice has traditionally been anchored in a wide range of predictable source types and formats. But as the legal information environment has shifted from print to online, the volume of available information, much of which is potentially relevant, has become increasingly unwieldy. Reliable resource types have expanded. Access points for resources have been relocated. We could once find legal information in known, predictable formats, published on a timeline controlled by the realities of print publishing. Now we find relevant resources sprinkled throughout open online sources, including websites, public databases, blogs, social media, and in AI-generated content. And paradoxically, much of this online legal information ecosystem is still defined by, and at times constrained by, traditional formats and source types. Savvy legal researchers must therefore be conversant in both paradigms. They must be able to recognize the old formats and access points — and the advantages and limitations associated with them — but also successfully navigate the range of information available online, and all the muddy in between that comes with it.

It is a tricky place to stand, as a legal professional. The key to keeping your balance is information literacy, which we present here as a key competency in legal-information seeking.

To understand information literacy, it’s helpful to start by exploring the nature of information seeking itself. Information seeking can be defined as any activity or behaviour of an individual with the goal of locating or identifying information. However, this is a barebones definition for a complex human behaviour with rich social, psychological, and affective underpinnings. Scholars in library and information science embrace a broader definition for this term, acknowledging how the context of human experience informs the actual process of “search”:

Information seeking is a term that describes a collection of fundamental human processes that enable survival and growth. Some elements of information seeking are involuntary and continuous elements of consciousness, but most studies of information seeking focus on conscious processes that tend to be grouped under the name ‘search’. In the 20th century, industrialization led to an informated society, which in turn has made searching for information one of the basic skills of 21st century modernity. Information work is seldom solitary, and most information is selectively shared at different stages of the information life cycle. Not only do people collaborate to create or analyze information, but they often collaborate on the seeking processes.[1]

We concur that the process of seeking information in the 21st century is intricate and multifaceted. In this text, we acknowledge the intricate nature of human behaviour within this context, even as we use the simple term “information seeking” to refer to it.

The foundational skillset that facilitates effective information seeking is information literacy: “the set of integrated abilities encompassing the reflective discovery of information, the understanding of how information is produced and valued, and the use of information in creating new knowledge and participating ethically in communities of learning.”[2] Information literacy places at the heart of any information-seeking task the individual’s ability to successfully find, assess, use, and apply information, regardless of format, access point, or paradigm. It is about where, how, when, and why to find information, rather than how to use a specific database, search engine, or research tool. Information literacy promotes search agility in a way that empowers an information seeker in the online environment. It also more easily facilitates the transition to new information-seeking technologies and paradigms, such as those currently being ushered into the world under the umbrella of AI.

In the narrow context of legal research, information literacy is well-defined by the American Association of Law Libraries’ (AALL) Principles and Standards for Legal Research Competencies.[3] AALL states that an “information-literate legal researcher” demonstrates the following five competencies:

- Possesses foundational knowledge of the legal system and legal information sources.

- Uses effective and efficient research strategies.

- Critically evaluates information.

- Applies information effectively to resolve a specific issue or need.

- Understands the ethical and legal issues surrounding information.

These are the principles that will guide your learning in this text. You may notice that these competencies are clearly paradigm-agnostic; in other words, they do not reference the print environment or the online environment but instead constitute an overarching skillset that becomes relevant at the nexus between the researcher and the ever-evolving information ecosystem. In other words, this skillset will grow with you as a researcher and is not dependent on any particular search environment. It is as important when you use an AI-driven legal research tool as it is when you pull a book from a shelf.

Moreover, information literacy touches on more than just your ability to find information. Under the third competency point above, it also plays a crucial role in the stages preceding and subsequent to information seeking. Critical evaluation includes having the necessary understanding of the legal system to determine the type of information required as well as how and where it can be accessed. Similarly, once the information is obtained, it must be evaluated based on its inherent characteristics and its suitability for use in client-centered problem solving. These themes will reoccur in the chapters that delve into specific legal resources, both primary and secondary, including traditional and non-traditional secondary sources, case law, and legislation. Both the final two competencies above will be engaged as we discuss broader topics such as confidentiality and privacy, AI and legal research, and critical legal research.

We believe that in the modern legal research context, and particularly in the online legal research environment, these competencies are essential. Information seeking has often been viewed as a “preliminary” activity — one that is inherently less valuable than the construction of an argument or other knowledge creation.[4] We believe that effective legal research in the current information ecosystem can only be taught if we focus in depth on the information-seeking behaviour and mindset that precedes synthesis and analysis. Our goal in this text is to prepare researchers to engage critically with resources, and the processes by which they were obtained, prior to relying on them for problem solving.

Information literacy may, for you, be a new way of looking at the online information landscape. It may be uncomfortable, including as it does a whole new set of vocabulary used to describe source types, research techniques, and search strategies. In the following sections, we provide a brief overview of some of the most essential elements of information literacy. These concepts, taken together, will equip you will a powerful set of skills for effective and efficient online information seeking.

1.1.1 Glossary of Research Terms

A skilled researcher employs a variety of tools, techniques, and access points in creating strategies for information seeking online. To communicate effectively about these strategies, you will need a specific vocabulary to facilitate clear and accurate descriptions and explanations of your research process to others. It will also assist you in tracking and documenting your research process for yourself.

We’ve created a glossary at the end of this book with definitions of specialized terms. These terms are set in boldface throughout this text; if you are using this book online, you can simply hover over the term to view its definition. The glossary is not exhaustive and new words may be added over time. We encourage you to review the glossary before you continue reading this section.

1.2 The Availability of Information Online

Given the prevalence and availability of online information in general, many legal researchers assume that everything they need for effective research and analysis can be accessed online, and that they will easily be able to identify where they can access this information by using a Google search. These are common assumptions but are they not accurate.

As the process of legal research moves online, it is easy to forget about non-digital formats that continue to exist but are not perfectly captured or replicated in the online environment. Many legal texts and treatises are still only published in print format.[5] Furthermore, even when publishers make these texts available on a paywall-protected digital platform like Lexis or Westlaw Edge, they may not be discoverable through common online search techniques like googling.

1.2.1 Semi-visible Online: Print and paywalled resources

Many resources that are not freely available online still tend to have an online presence of some sort. Consider the following example: Waddams’ Law of Contracts, a leading legal text now in its 8th edition, is published in print and through Carswell’s ebook platform ProView. ProView is accessible by subscription only, which means that a paywall prevents anyone who does not pay for the book (either as an individual or through a library, firm, or other organization) from accessing it. This means that a search engine like Google cannot index the full text of this book, so you cannot access it from a Google search.

The resource, however, may still be visible in the online environment. Information exists about this text online, even if we cannot read the full 700 pages without pulling the physical book off a library shelf or subscribing to the ebook platform. In other words, even when a book is available only in print or by subscription online, we can still use metadata in the online environment to identify that a resource exists and to evaluate its potential utility for research. That metadata includes useful information like a resource’s title, description, or table of contents. But identifying a resource like Waddams’ Law of Contracts in the online environment can be challenging because our default search strategy — keyword searches in a search engine — is often too granular to capture higher-level information. For example, a keyword search for “force majeure” in an online search engine or library catalogue will display many results, but it won’t retrieve Waddams’ Law of Contracts, since the full text of the book is not searchable online. It is available online (e.g. via ProView and a library catalogue) but it is not easily and broadly searchable online; it is a semi-visible resource in the online environment.

While semi-visible resources are most often traditional secondary sources, the online availability of primary sources of law also has its limitations. Although the majority of reported Canadian court decisions with written reasons can now be accessed online, the availability of unreported decisions, oral judgments, and court filings varies significantly. As with secondary sources, a researcher may need to use the online environment to determine the existence of a resource before requesting the document from the court. Similar variability exists in the online availability of historical legislative materials, which differ greatly between jurisdictions.

It is important to appreciate that a particular source may be exactly what you need, even if its full text is not available online. Later in this text, we’ll discuss specific resource types and which strategies are most useful for locating them. The more you practice locating different types of sources, the easier it will become to build effective information-seeking strategies in the online environment.

1.2.2 The Prevalence and Use of Google

For many, Google[6] is a go-to starting point for any research question or information need. There’s good reason for this. The search algorithms are reliably good at surfacing relevant online content based on natural language queries, which means you don’t have to put as much effort into devising search terms as you would in a more traditional database. Googling is also often an effective way to quickly locate government information, including current, consolidated statutes that are published online.

We are especially tempted to rely on Google or other search engines for legal research because we think of it as free.[7] While there are no disbursement or overhead costs tied to hitting the search button, you should still beware of the time cost (which may be billable time). This can quickly accrue when you are following tangents and sifting through a large volume of Google results, looking for authoritative and relevant resources. Consider the following caveats to maximize effective and efficient use of Google as a first-line search in your research process.

First, Google does not search everything that is available online. Google only indexes information found on publicly available webpages (i.e. it records the content or information about the content). But this method of indexing information privileges certain types of resources over others. A Google search is more likely to retrieve blog posts, news articles, informational websites, and open- or community-generated content (think of Wikipedia) than it is to retrieve authoritative treatises like the Waddams text used in the previous example.

There are some extremely important resources, both in print and online, that are not accessible to Google’s crawlers, like the databases and tools in Westlaw or Lexis’ legal research services. As a result, these will be invisible to the Google searcher. If you limit your search to Google, you will miss entire categories of sources — especially legal secondary sources like textbooks, treatises, looseleafs, and encyclopedias. The full text of these resources are not typically accessible to Google, even if they exist online in a digital format. Other resource types, such as scholarly articles, may be indexed by Google but are similarly inaccessible because the publisher has placed a paywall on the content. Even publicly accessible, online Canadian case law can be difficult to search on Google, since CanLII does not allow most of its case law databases to be indexed by search engines.[8]

Second, Google returns results based on popular — not legal — criteria. If you’re evaluating sources as a legal researcher, you will likely do so with certain key legal principles in mind such as stare decisis and jurisdictional considerations. Google has not been programmed specifically to meet professional parameters such as these. Yes, Google can deduce some information about its user and tailor search results accordingly (like using your device location as a factor). But often results are ranked based on other factors like how many times a keyword appears in a webpage or how often a website is accessed. This can lead to many irrelevant results in a Google search on a legal topic — for instance, results prioritizing American blogs and websites. These are common search hits and do not always explicitly state the jurisdiction of information; you may need to spend some time investigating a suggested website to determine its relevance.

Third, Google does not care if an author is an “expert”. One challenge with secondary sources in the online legal research environment is the illusion of authority. Search engines like Google may not have access to the full text of many traditional secondary source types, and will often instead point researchers towards less authoritative source types such as blogs. When these appear in your search results, you may assume they have a weight or influence that they don’t actually have. Further, since Google is a major access point for attracting web traffic, companies will often use strategies like repeating keywords to increase web traffic to their website by boosting the site’s ranking in a results list. Factors like whether the author has a degree in the field, has practiced or published in the area of law, or has other relevant expertise in the subject matter, are not considered by the Google algorithm when returning or ranking results. A careful review of an author’s expertise, and the accuracy of the content, is therefore essential in order for for a user to determine whether a search result can be relied upon as a source in legal research.

So when should we use Google as legal researchers? Despite these caveats, Google remains a key tool when embarking upon a legal research task. It is a useful entry point if you have been tasked with researching an issue and have no clue where to start looking. For example, if you’ve been asked to research a shotgun clause, but don’t know the type of document in which such a clause would be found, Google may at least point you in the right direction. Similarly, in the beginning stages of research, you will also be jotting down keywords, synonyms, variations of a phrase, and related concepts. A Google search can often help you quickly identify at least some relevant keywords, so that you have a head start in tracking down relevant materials in more fruitful access points like your law library, a legal database, or the major legal services.

Google is also useful if you are looking for a specific source that you know is available online. If you’re seeking the current version of a statute and you know the official consolidated act is on the Justice Laws website, you can navigate there much faster using a Google search. But be warned: you still need some important context to conduct this type of information retrieval with Google. Names of annual statutes (source law) and consolidated statutes (current law) may be virtually indistinguishable, so you must have enough knowledge to determine if you are looking at the right version of the statute on Justice Laws once Google has brought you there. For novice researchers, it may be easier to start on the Justice Laws homepage and click into the correct database than to use Google as a short cut.

Lastly, Google is especially useful for researching emerging areas of the law where little primary law exists and where more traditional secondary sources have not yet been published. See Chapter 5 for more information about the types of resources returned in a web search that can be useful here.

1.3 Essential Background for Using Legal Databases and Services

As we’ve already described, Google and other search engines do not interact well with legal databases — even those publicly available on CanLII. Knowing the basic fact that legal databases exist outside of Google is the first step in locating legal information effectively. But what exactly is a legal database?

1.3.1 What is the Difference Between a Database and a Service?

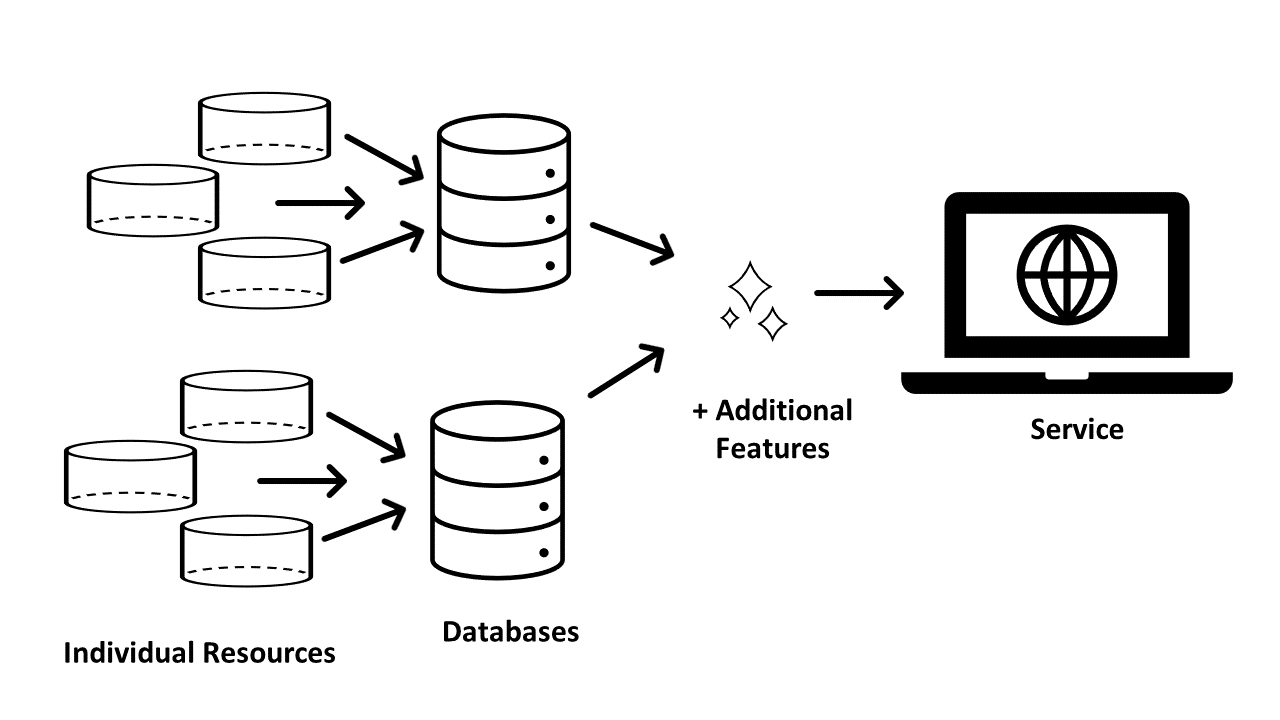

First, it is important to understand the difference between a database and a service (see Figure 1). In this text, we use the term database to refer to a digitized collection of individual resources — often documents, but sometimes other types of records as well — that have been standardized[9] to allow for search and retrieval. Consider CanLII’s list of Primary Law Databases: note how this list is presented as individual databases from each court or tribunal with notes that cover when each database was last updated and the number of documents in each.

Figure 1: The relationship between databases and services.

A legal research service, on the other hand, is a collection of research tools and databases available from a single access point. A service provides a wide range of information and may also offer additional value-added elements (like annotations or classification schemes), as well as useful tools or integrated functionality to facilitate searching. CanLII, for example, is a service because it provides multiple databases (e.g. case law, legislation, secondary sources), all searchable from one access point (canlii.org), and with additional features such as a citator tool and subject classifications. CanLII is a free service; Lexis and Westlaw are both subscription-based commercial services. CanLII, Westlaw, and Lexis are the three major Canadian legal research services, though there are emerging commercial competitors.[10]

When it comes to searching, each service allows you to search across its entire collection of databases (from the Google-type search bar on its homepage) as well as to drill down into a specific database (e.g. Supreme Court of Canada decisions) or a subset of databases (e.g. all Canadian case law). Your experience with Google may lead you to use the broadest approach, but this is usually an inefficient way to conduct legal research. A service can contain millions of records, and weeding through a results list with thousands of items can be confusing. This is especially true if those results include disparate types of resources, such as sections of legislation, pleadings, forms, and legal memoranda, as well as cases and secondary sources.

The alternate approaches are a form of pre-search filtering and is generally more efficient. It not only makes your search results less overwhelming, but will also increase your options for manipulating the individual resources to display in ways that meet your research needs. This is because a service standardizes specific types of resources to allow you to better search them; for instance, searching case law by subject classification. These more tailored options will only appear from within the specialized databases themselves, rather than from the service’s general search. Look for either an “advanced search” option or a filter on your search results page. We will discuss specific strategies for retrieving types of resources in each relevant chapter in parts II and III of this text.

1.3.2 Questions to Ask about a Database

Once you’ve identified a potentially relevant database in a service, you’ll need to understand certain characteristics of the database before you can use it effectively. Consider the following five key questions which are expanded from Ken Fox’s Slaw series on this topic:[11]

- What constitutes a record in the database? A database is a collection of records — individual documents that you can search across. To answer this question, think about what sorts of items will come up in your results list. For example, if you are looking for case law, is your search going to retrieve full-text versions of a case? Or are your results case summaries? Or are they case digests? You need to understand what you’re searching across to effectively use the database.

- What is the database’s scope of coverage? Every database has some type of limitation on the information it contains. Most databases will include a sidebar or pop up box called a scope note where this information is found (look for “information” icons, often indicated by the letter “i”). Scope may be defined using a number of dimensions including chronology, geography or substance. Is it a topic- or discipline-specific database? Does it deal with information from a single jurisdiction or geographical region? What is the date of the oldest information in the database (how far back in time does it cover)? How recently has information been updated or new documents added?

- What is its search syntax? Most databases allow you to perform a keyword search using either natural language or Boolean search (discussed later in this chapter). However, not every database uses the same set of Boolean connectors or interprets natural language in the same way. Symbols may differ: a wildcard symbol may be an exclamation point in one database and an asterisk in another. Connectors like a typed space may be interpreted quite differently by the search engine: an AND in one case and an OR in another. The system may automatically search plurals and word variations, or you may have to specify which variations you want to capture in your search. To ensure that your search will yield the results you expect, be sure you are using the correct Boolean connectors for that database. To find a list of relevant Boolean connectors, navigate to the search help or advanced search information page for the database.

- How are my results ordered or presented? Often a database will default to showing a results list ordered by “relevance”. However, this is often a difficult metric to understand, since we seldom know how the search algorithm for that database makes decisions about what constitutes relevance. In other words, the database doesn’t usually give you much information as to how it determines which results are more relevant than others. In some cases, it may be useful to view results ordered by most relevant to least relevant, but in others it may be more useful to see results ordered in other ways such as newest or oldest first (chronological or reverse chronological) or alphabetically. Some services are also starting to present database results in more creative ways than a list, such as the visual “Search Tree” on Lexis . Explore the database you are using to see if it permits you to change how the results list is ordered.

- What is the database algorithm’s bias or “point of view”? As you’ll see later in this chapter, most search technologies in use today rely on algorithms that obscure how and why certain results are selected or promoted in your results list. You as a user are not able to see the basis on which the algorithm makes decisions about what to return in your results list. As Susan Nevelow Mart puts it, the algorithm has a point of view.[12] As a piece of search technology built by a specific group of people working within a particular corporate culture, any algorithm has biases and assumptions built right into it, which can differ dramatically from one database to the next. While you may not be able to find clear answers about an algorithm’s behaviour, you can get a better idea of how it operates by running your search in a similar database and comparing the results.

You are much more likely to use a database effectively and efficiently if you spend at least some time trying to find the answers to the above questions.

Every Algorithm has a POV

In 2017, Susan Nevelow Mart conducted a fascinating study by recreating the same searches in 6 case law databases and comparing the top 10 results. Results showed that approximately 40% of the top 10 cases were unique to a database — in other words, they were not in the top 10 results for any other database in the study. Mart concluded that “every algorithm is very different, and every database has its own point of view […] researchers cannot rely on the black box of the algorithm and be satisfied with their initial results”.[13]

1.4 Fundamental Search Techniques

Search techniques are behaviours that a legal researcher uses when seeking information. Of all the possible online search techniques, keyword searching — either with Boolean connectors or natural language searching — is likely the most familiar. However, there is a range of techniques beyond keyword searching that you should be familiar with. You will become a more effective and efficient researcher if you expand your repertoire of search techniques and learn to deploy them flexibly in your research.

Not every technique can be used in every database, but the techniques described below are standard across the major legal research services (CanLII, Westlaw, and Lexis), with differences noted where applicable. Each is referred to by a name that you can use when discussing research with others or when recording your own search process.

1.4.1 Keyword Searching: Boolean and Natural Language

Keyword searching is familiar and intuitive. The advent of computer-assisted legal research brought this technique to the forefront of most researchers’ minds and search repertoire. It is the most common approach to searching in an online environment, so much so that it may be your default setting for research. But the process of generating and extracting keywords, and then using them for resource searches, should be approached mindfully and with some caution (for more information on the process of generating keywords, see Chapter 2). There are two main types of keyword searching, but let’s first look at how keyword searching evolved, how it works, and consider some possible pitfalls. There are some important caveats to keep in mind, most of which stem from what is happening when you retrieve information based on keywords.

Keyword searching, as we now know it, has not always been possible or easy. In a print environment, researchers “keyword searched” by using their eyes and brains to spot words that they deemed important in tables of contents and indexes of print volumes. Information systems advanced rapidly however throughout the 1970s and 80s until the point in the early 1990s when workable search engine algorithms met digitized data and the web. At this point, web-based interfaces were very new and the algorithms not yet particularly sophisticated. Even a search of offline materials — for example, digitized content provided to users on a subscription basis in the form of a standalone CD-ROM — could present challenges based on the organization of data on the disc. As these issues were resolved, however, it became easier and easier to access an enormous volume of information using fairly simple search techniques: navigate to an access point, type some words into a search box, hit return, and wait for your results. And therein lies the basic challenge associated with modern keyword searching: easy access to huge volumes of information.

When you conduct a keyword search, you are asking the database’s search algorithm to take the terms in your search and look for matches between your keywords and the text of each record in the database, within the parameters defined by any Boolean connectors you use.[14] This type of search will retrieve every record in which your keywords appear, whether or not any given record is conceptually related to your keywords. In other words, the algorithm is looking for mere matches between your search terms and the words found in the database. Such a search may generate a huge volume of results, many of which may be “false positives” — records where your search terms do exist, but which have nothing to do with the topic of your search. Similarly, if you haven’t used the right word to capture the concept or topic, your search may miss important results — after all, the algorithm is simply looking for a word match, not a concept match.

The use of Boolean connectors in a keyword search can improve search results, but many users lack confidence in their ability to correctly use Boolean connectors. As a result, for many, keyword searching is an inefficient approach to research — especially if your firm is billing each search you conduct in a legal research service — unless you know how to leverage the search functionality of the database to your advantage. To do so, you need to understand that there are two major types of searches available within a given database: natural language and Boolean (or “terms and connectors”) searches.

Natural language search refers to search technology where a user enters just that: language as they would naturally speak or write. We tend to assume that every search bar we see in a database or service is able to parse this type of search, since it has become the industry standard with Google and other online search engines. While the legal research services have been improving their natural language capabilities, it is much more difficult to retrieve legal information via this method. It often exacerbates the above-mentioned problems by either retrieving a huge volume of results or missing important results, or both.

Boolean connectors can make your search more efficient by allowing you to direct the search engine to treat your search terms in a certain way. Boolean connectors are symbols or words such as AND (&), OR, and NOT, which specify the relation between keywords that you want to see appear in a result (e.g. drunk AND driving). A well‐structured Boolean search — one that contains appropriate keywords, synonyms, and connectors — can be very effective. In the ideal case, it returns a manageable population of results which are uniformly relevant to the legal issue in question. However, the success of such a search is directly dependent on your knowledge of the Boolean connectors that function in the database you are searching, as well as on your ability to generate relevant keywords and synonyms. Not all databases or services use the same search syntax. The Boolean connectors trigger certain operations that differ across databases. If your keyword or Boolean technique is still developing, there can be distinct disadvantages: a huge volume of results, missed results, or false positives.

To complicate matters further, you may not be able to easily predict, as a user, which type of search is the default setting for the search box in which you are about to type. Not all legal research services default to the same type of search in the search box. Pay particular attention to which types of searches are supported, and how or where to switch between natural language and Boolean search as needed. For instance, Westlaw automatically runs a plain language search even if you use certain Boolean operators such as AND, OR, and “” (phrase). To deliberately run a Boolean search, you must force it to interpret these as operators.[15] CanLII, on the other hand, will interpret your query as a Boolean search no matter what, because every query is processed according to CanLII’s Boolean syntax. These distinctions highlight the need for you to always investigate the search documentation provided by a service before conducting a search. In Westlaw, this information is available by opening the “Search Tips” pop up from the homepage. On Lexis, go through the search documentation in the “Help” section.[16] On CanLII, this information is on the “Search” page.[17]

Often, the best approach is to combine keyword searching with another technique, like subject-based searching (find a generally relevant topic and then do a keyword search within the contents of that subset) or filtering (perform your keyword search then apply filters to narrow your results). This combined approach will help you narrow the focus of your search so that you do not retrieve an overwhelming number of results.

1.4.2 Browsing

Browsing is a way of briefly examining a service or database for information that aligns with your research topic. To use this technique, you must first have done some thinking about your topic, to generate keywords and synonyms that accurately describe the area(s) of law and the legal issues relevant to your client’s problem. You must also have an access point at which information about the resource’s contents is presented in an organized hierarchical fashion — in other words, a table of contents or an index that can be scanned for keywords, phrases, and concepts. Browsing can be used with print books or ebooks (which have both a table of contents and an index) as well as with other databases that offer some form of table of contents or index, like online legal encyclopedias and case digest databases. In this sense, browsing is closely related to subject-based searching (see below).

Browsing can also be thought of more broadly when used in tandem with early-stage exploration. For example, Lexis and Westlaw provide additional access points for browsing by grouping resources under a specific subject matter (called “Legal Topics” in Westlaw and “Practice Area” in Lexis). These provide a browsable collection of resources that include both primary law databases and secondary sources. Users can browse these results to get a sense of the scope of available material, mine the results for more keywords, and access particular sources to learn more about the area of law they are researching.

1.4.3 Filtering

Filtering is another technique usually used in tandem with keyword searching or browsing, although it can be used with results lists of all kinds in all three services. It is an effective way to reduce the overall number of search results retrieved to a more manageable population. You can use this technique with any other, so long as you have a results list to work with and a set of criteria that you can impose on those results.

Filters can be used either before (using an advanced search function) or after your search is conducted. When used prior to a search, filtering limits the number of records over which your search is run. Only records that meet the filter criteria — level of court, jurisdiction, date range, resource type — are searched, and results are drawn from that population. However, there may be a distinct disadvantage to this approach, in that you may end up narrowing the results of your search too soon and miss something. Consider adding and removing filters flexibly and strategically as you search.

When these criteria are offered as limiters that you can apply after your search is conducted, to only look at certain subsets of your results — say for example, after you do a broad keyword search — they are sometimes called “facets”. These options usually appear on the left side or across the top of your results page, depending on the service you are searching.

You can filter in all three services. You can even pre-filter on Google, using the advanced search function.

1.4.4 Subject-based Searching

Subject-based searching is a powerful search technique but is only available in a limited number of databases. Subject-based searching allows you to see and choose from a list of topical categories, and then browse or search within that category, where all information contained there is about that topic.

In order to classify information according to topic, two things are required: first, an established taxonomical framework for classifying information; and second, some means by which to impose or assign classification on content within the database, whether that is achieved by human database classifiers or by AI. This classification of information by legal subject matter is a key feature of databases that allow subject-based searching. The set of agreed-upon terms that comprise the taxonomy of topical classifications is called a controlled vocabulary. A controlled vocabulary is a special tool, in that the words chosen are used to represent concepts, not just specific words. For example, the concept of drunk driving can be expressed using several different phrases and terms. But with a controlled vocabulary, the classifiers establish one term or phrase to represent the concept (like “drunk driving”). Every record conceptually related to the idea of drunk driving will be labelled the same way, regardless of the words used to denote the concept.

When you search on this basis, you can find records in the database that are conceptually related to the term used to describe the concept, even if the exact term is not used in that record. Each record in the database is categorized in accordance with one or more terms drawn from the controlled vocabulary. Terms at the topmost level identify the broadest level of classification. At the lower levels, classification terms may be quite granular. But all the information in the database is given a place in the hierarchy of topics.

Here is an example of subject classification drawn from the Canadian Abridgment Case Digest database. This is a classification in the top-level area of contract law. As you can see, as you descend the hierarchy of terms in the controlled vocabulary, the terms become more and more specific:

Contracts

–Formation of contract

—Duress

—-Psychological duress

At various levels in the classification scheme, you can access resources (in this case, case digests) that have been assigned to that classification in the database.

This classification system creates both advantages and challenges. If you can identify a top-level classification and subheadings related to your topic, you can find all the information contained in that database, on that topic, in one step. This is true regardless of the specific words that might be used in each record to refer to the concept that is of interest to you. On the other hand, you may not always know what the relevant top-level term is for your topic. For example, if the database classifies all information about drunk driving under a subject heading called “Operation of vehicles while intoxicated”, this may not be obvious to you. Other disadvantages include the fact that subject-based searching is less surgical. If you are looking for information on a very specific concept, that concept may not have a topical category all to itself. Lastly, terms in the taxonomy can take time to catch up to emerging areas of law or may misrepresent areas of law due to the perpetuation of historically dominant perspectives.

1.4.5 Chaining, or Cited Reference Searching

Chaining or cited reference searching is a highly intuitive technique. It can be used wherever you are beginning your search process with at least one useful resource in hand. To be useful, your resource must cite other resources, and be able to be cited by other resources.

Consider, for example, a journal article; a common “good source”. Journal articles do indeed cite other sources and can themselves be cited by other sources. Imagine you have chosen an article because it is highly relevant to your research. As the author was writing, she cited other, earlier works by other authors. We assume she cited these because they were relevant to her topic. These are the cited references, and they will typically appear in footnotes or endnotes to the article, as well as in a bibliography or table of authorities.

Once the article was published, it in turn could be cited by other authors. Again, we assume that other authors would choose to cite this article because it was topically relevant to their work. These are the citing references. They can be a bit harder to find. One approach is to view your original “good source” on a service like Google Scholar or the Dimensions app, where it is possible to see all other sources that cite your one good source. The assumption here is that if you begin with a source that is highly relevant to your topic, you will find other similarly relevant resources within the population of cited references, and within the population of citing references. In other words, you parlay your one good resource into many by using the web of citations and references.

Some databases and services provide hyperlinks that redirect or cross-link related information between tools and/or databases. This feature can expedite the process of chaining and is possible in Lexis, Westlaw, and CanLII. For example, in the Canadian Encyclopedic Digest, the text of an article includes hyperlinks to the database record for the corresponding full-text primary sources of law (cases and legislation) discussed in that article. In a full-text view of a case, cases cited by the court in its decision are hyperlinked and you can navigate to the cited cases by just clicking on them — you don’t have to do another search. Be alert for hyperlinked or cross-linked information, as it is an opportunity to expedite your research.

1.4.6 Monitoring

Monitoring is something of a hybrid between a technique and an information-seeking strategy. It is an active choice to follow and incorporate certain types of legal information into your research workflow. In this sense, it is an essential means of achieving current awareness: the state of having up-to-date knowledge on a legal topic. Current awareness is a difficult concept, as it is sometimes confused with simply searching non-traditional secondary sources like newspapers or web-based newsletters. Without monitoring, however, a one-time search of non-traditional secondary sources provides merely an illusion of current awareness. It is the difference between simply stumbling upon some information as a result of a search, versus actively controlling an information stream to bring certain types of information from certain resources directly to you on a periodic basis.

For example, blogs may be considered current awareness tools but only insofar as you have actively incorporated new entries into your workflow via monitoring. Consider a blog post from 2012: there is nothing current about this information resource, and viewing this old post in your web search results will not contribute to your state of current awareness. Just because something is online does not mean it is current. Indeed, as the internet matures, it will continue to host a higher and higher proportion of outdated information. But by actively subscribing to receive updates from that blog — in other words, by monitoring that blog — you create an automated information stream that allows you to keep abreast of any new developments.

Monitoring is not just for non-traditional secondary sources in a certain practice area. It can involve tracking a specific case or statute, as well. If you’ve identified an important case, you can monitor the case to know if it is cited or appealed. If you’ve identified a key statutory provision, you can monitor it for amendments or coming into force. Your individual current awareness needs will of course vary throughout your career, depending on your role and professional environment. The key here is to integrate monitoring into your day-to-day information-seeking behaviour by leveraging tools that enable you to track case law, legislation, and/or secondary sources. As a general rule, look for “subscribe” or “alert” options on a website, within a database, or on a search results page. We identify some specific monitoring tools, broken down by resource type, throughout the remainder of this text.

1.5 Artificial Intelligence in Legal Research

AI is all around us as online legal researchers and comprises both generative and non-generative traditional (or discriminative) tools. AI is a key component of Google, but it is also embedded in the major legal research services in ways that are not always obvious to the user. For example, Westlaw and Lexis integrate AI into their natural language search technology, but also into standalone products that are more heavily advertised as AI-driven, such as Westlaw’s KeyCite Overruling Risk and Lexis’ Brief Analysis tool. Both companies have announced plans to integrate generative AI — the type of technology that includes ChatGPT — into their platforms in their next iterations.[18] In the early 2020s, even CanLII started integrating AI by using it to automatically generate subject classifications for case law.

AI may seem at odds with more traditional research strategies, but any researcher’s interactions with an AI-driven tool should be treated in much the same way as those with a more traditional database. The information literacy principles we use to inform our use of case law or journal article databases are, in essence, the same ones we require to effectively interrogate the information that an AI tool is trained on, interacts with, and delivers to the user.

AI will surely continue to permeate the legal research landscape in new and imaginative ways in the coming years. As these technologies become increasingly intertwined with legal research tools, a basic understanding of what AI is and how it works is necessary so that the savvy legal researcher can leverage it effectively alongside more traditional approaches to information seeking.

1.5.1 Introduction to Artificial Intelligence

The label artificial intelligence is given to a range of technologies, both traditional and generative, that allow machines to simulate human cognitive abilities or perform tasks typically associated with intelligence. Currently, AI-driven tools do not have the capacity for actual “intelligence”. Instead, they rely on a machine’s ability to identify, replicate, and predict patterns based on enormous datasets, and in response to specific targeted tasks that are set by human users. Thus, in online legal research, AI is most useful when applied by a human user to a well-defined, discrete legal task or problem. Indeed, the most sophisticated examples of AI in the legal industry today are tools that use a “human in the loop” approach. That is, they do not rely solely on the machine’s ability to teach itself a task based on a dataset; they also rely heavily on human involvement and feedback to refine the AI tool’s outputs more adequately to human standards. ChatGPT is a good example of how this strategy works. The chatbot’s large language model was initially trained on web-scraped text, but was further refined based on human feedback, especially regarding more sensitive aspects of text generation like the avoidance of offensive or harmful text.[19] Tailored legal research tools rely on the human in the loop even more extensively. For instance, AI tools used by research services to generate research memos are sometimes partnered with human researchers, who review the AI product for accuracy and supplement the analysis before it is sent to a customer.

In the legal research context, AI use augments, and in some cases supplants, the intellectual work of the researcher. For example, the traditional Boolean search technique allows a user to be very precise about the terms and connectors – and the relationships between those terms and connectors – that are used to retrieve search results. The researcher applies considerable knowledge and judgement to predict how these terms may appear in the desired results and modify the search string to ensure maximum relevancy and efficiency. In contrast, an AI-driven natural language search engine removes that level of control from the user and instead relies on the machine to interpret the meaning of a researcher’s query and return results, some of whcih may be more or less relevant. Much of the cognitive work here has been shifted to the machine and the individuals who developed the algorithm behind it. Further, because these technologies are usually proprietary, the researcher may not have any insight regarding how the machine is interpreting a query or why it is returning certain results.

This shift has important consequences for lawyers who still, ultimately, shoulder the responsibility for using these tools appropriately in the practice of law. It is important to understand our natural tendency to trust the results of an AI-generated tool because of automation bias: the human tendency to favour decisions made by automated systems (especially in situations where the human feels less expert) instead of making the effort to verify or seek out information themselves.[20] One good analogy for the proper approach to use of AI in legal practice is the relationship between a junior and senior lawyer. Even though the junior associate may be doing the bulk of the work, the senior lawyer is still responsible for supervising and directing the junior, ascertaining the validity of legal authorities and legal conclusions, and delivering legal advice to the client. The same is true with an AI system — just because you are using a machine does not relieve you of the responsibility to provide accurate legal information to your client.

1.5.2 How is AI used in Canadian Legal Research Tools?

As with most new technologies, AI tools in legal research are being developed and deployed more broadly and quickly in the U.S. Since there is such an enormous amount of publicity surrounding these advances, it can be difficult to cut through the hype and headlines to get a realistic idea of what is available to a Canadian legal practitioner.

The following are some major categories of AI-driven legal research tools available in Canada as of 2024.

1. New search technologies: While prior systems required strictly controlled search syntax, new search engines in both Westlaw and Lexis allow for and encourage natural language searching across their many databases. Other tools like Lexis Brief Analysis and vLex’s “legal research assistant”, Vincent, allow you to upload your own document for analysis. The system will then recommend additional case law that you may have missed in that document. These two examples represent fundamental departures from how case law has been searched in the past.

2. Improved citators: Online citators have long existed in Westlaw, Lexis and CanLII and all three permit a “manual” analysis of stream of precedent. AI-driven citators move legal citation analysis a step further, by promising to automatically detect when a case has been implicitly overruled by another case (instead of just explicitly). In Canada, Westlaw Edge currently provides access to Westlaw’s improved AI-powered citator, KeyCite Overruling Risk.

3. Legal “answer” tools: AI-driven systems that aim to pull “answers” to legal questions from existing materials like cases or legislation. For example, Lexis Answers matches natural language queries from the main search bar to “answers” drawn from case law.

4. Subject classification systems: Subject classification of data used to be a specialized task that was only accomplished by humans and was therefore only available via large publishing services like Westlaw and Lexis. Recently, however, CanLII has experimented with adding AI-generated subject classifications to case law documents, which allows the user to filter by subject.[21]

5. Analytic and prediction tools: These tools leverage AI to predict the outcome of a scenario by analysing previous cases with similar factors – basically, legal reasoning by analogy. Prediction tools usually focus on very specific legal issues, such as worker classification, constructive dismissal, and reasonable length of notice. For example, Blue J Legal is one company using AI to predict outcomes in the areas of tax and employment law. MyOpenCourt is an open access suite of Canadian predictive tools. Other predictive tools focus instead on analysing your likelihood of success in front of a certain judge or court, such as Lexis’ Context.

6. Generative AI: Tools that create entirely new content such as text, images, video, or other media (text generation is typically the focus in the legal industry). Some companies, like Alexi, use a combination of AI and humans to generate a legal research memo. Other generative AI tools are chatbots that will generate text based on prompts from a user. The most famous example of generative AI is, of course, ChatGPT, which took the world by storm in 2022, and then quickly made one lawyer infamous for his faulty reliance on the tool in court.[22] Generative AI chatbots in the Canadian space include Jurisage’s “chat with a case“ tool and Codify’s “talk to legislation“ tool. This technological space is moving quickly. Lexis and Westlaw have both now integrated generative AI, although only Lexis’ tool is currently available in Canada.

While this is certainly not a comprehensive list, these general categories are useful aids in helping a novice legal researcher identify when and where AI is being used throughout the products that are currently available in the Canadian market.

1.5.3 The Three Layers of an AI-driven System

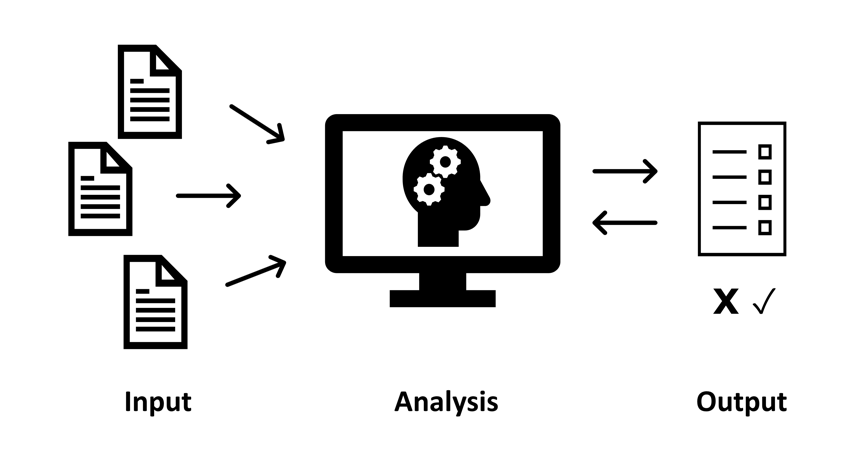

A detailed technical understanding of how AI works is unnecessary for most legal researchers. But in order to build information literacy and thereby understand an AI tool’s suitability for a given research task, it is helpful to understand the three main components of any AI system. These can very broadly be described as input, analysis, and output (see Figure 2).

Figure 2: Three layers of an AI-driven system.

The input layer refers to the dataset (the information) that the system is trained on and/or runs on for the purposes of task completion. Both traditional and generative AI operate based on pattern detection: in other words, these tools use rules and patterns in existing data to predict the correct or desired result. Thus, the quality and quantity of the underlying dataset has an enormous impact on the quality of an AI tool’s output. A tool trained on a general-purpose dataset will be much less useful to a legal researcher than one that is trained on legal data. A tool that is trained on only Canadian case law will look very different from one that is trained on American case law. A tool that is trained on 10,000 cases will look very different from a tool trained on only 10.

In the second layer, the analysis layer, the machine examines and interprets its dataset through the prompt or task set by the user. The machine’s analysis can be influenced by direct programming by developers — for instance, programming the machine to give more weight to appellate court decisions versus trial court decisions, or programming a generative AI tool to avoid offensive words. However, the analysis may also be influenced in ways not obvious or understandable to the user, since these systems often detect patterns that are not discernable to humans. This opacity – the “black box” of AI – can make it challenging for users to understand how and why a tool is providing certain results, and even more challenging to identify its shortcomings.

The third layer is the output layer, which refers to the results or text generated by the tool in response to a task or prompt. The form of this output differs depending on the nature and purpose of the tool. It could be a list of documents that the AI has determined match your query, or an AI-generated legal memo, a predicted outcome for your client, or any number of other outputs. At this layer, many AI-driven systems incorporate “reinforcement learning from human feedback” (RLHF), an approach where humans interact with the tool and provide assessment of the quality of output, which is in turn incorporated into how the tool conducts analysis in the future. Training often happens both in the development stage (i.e. conducted by the tool’s developers) and also after a product is rolled out to users. For example, researchers using a tool may be asked to mark when results are useful, or data may be collected on how they interact with the output to determine its relevance and feed back into the analysis layer.

This feedback loop is one of the important characteristics of many AI systems. The machine “learns” and improves; this ability is partly why we attribute human-like qualities of intelligence to these systems.

1.5.4 Strengths and Limitations of AI in Legal Research

It can be difficult to accurately assess the utility of AI-driven tools for typical research tasks. As with any emerging technology, the limitations of these tools can be massive, underacknowledged, and often obscured by hype. The volume of commentary in this regard, as well as the marketing materials that accompany the roll-out of new AI-driven tools embedded as features in academic subscriptions, makes it even harder to discern the real strengths and limitations of such tools. The complexity is increased by the fact that AI is an incredibly wide-ranging area of technological development. A general-purpose generative AI system (like ChatGPT) may not necessarily have the same relevance to a specific discipline like law as it does for general use. Once you cut through this noise, however, it Become clear that these tools have specific strengths and limitations in the context of legal research.

Assuming an input layer that is fit-for-purpose, AI is most effective when applied to a specific legal problems that has a clear structure and definitive right or wrong answer. It is also well-suited to tasks that focus on identifying existing patterns in datasets, such as predicting judicial outcomes based on how courts have ruled in the past.[23] That said, there are many core legal services that are not well-suited to AI-powered assistance. Harry Surden provides a useful list of adjectives for understanding the areas of law in which analysis or task completion is not easily automated: “areas that are conceptual, abstract, value-laden, open-ended, policy- or judgment-oriented; require common sense or intuition; involve persuasion or arbitrary conversation; or involve engagement with the meaning of real-world humanistic concepts, such as societal norms, social constructs, or social institutions”.[24] In other words, AI systems are good at following existing rules and patterns, but are less adept at presenting novel, creative, or innovative approaches to law and legal problem solving. They are unable to grasp nuance or demonstrate some of the human soft skills associated with high-quality client service, such as compassion or empathy.

In addition to being ill-suited for certain types of questions, many AI systems run the risk of perpetuating bias in many forms. These tools are strongest at detecting existing patterns in datasets, which means they can very easily project prejudices that exist in a dataset into the present. Consider the infamous example of risk assessment software COMPAS, which predicted greater recidivism for Black defendants than White defendants.[25] These biases can be introduced unintentionally: even if race is ostensibly excluded as a criterion for consideration, there may be proxies for this factor in the dataset (e.g. socioeconomic status or postal code) that the AI system detects and factors into its determination. This lack of transparency into an AI tool’s decision-making process is often referred to as the program’s “black box”, which can make it challenging for a researcher to identify and mitigate bias effectively when using these tools.[26] A savvy legal researcher will use the information at their disposal to assess the risk of bias in a given tool and its implications for their research question.

Traditionally, legal research has been a time consuming and labour-intensive process. When applied to the right legal problem — such as the need to review large quantities of data, or spot patterns and how those patterns have been interpreted[27] — AI can be an efficient assistant, because a machine can conduct this type of work much faster than a human. This can help eliminate or reduce some of the more mundane aspects of legal research, and, consequently, bring great potential for cost effectiveness if you are billing a client for time spent conducting legal research.

1.5.5 Conducting Legal Research Using AI

The current state of AI is a dangerous one for the legal industry. Practitioners must be extremely careful to only leverage AI systems that add value to their work, rather than those that invent or muddle legal research, or are otherwise disadvantageous to traditional legal research methods. In extreme cases, a lack of awareness on the part of the researcher can lead to drastic consequences — like the New York lawyer who used ChatGPT to write a court filing in 2023, only to be sanctioned for his failure to realize that the chatbot cited fake cases.[28] Blind reliance on AI can be a career-ending move.

Instead, a savvy legal researcher needs to consider the utility of any AI system on an individual basis. That means working closely in or with a tool to identify its strengths and weaknesses before relying on it to conduct or supplement legal research tasks. Information is crucial: learn everything you can about the system and its layers by reading all possible documentation and by experimenting with the limits of the tool.

First, ask the most basic question: What is the purpose of this AI system? A general-purpose tool — not designed for law specifically — is far less likely to have relevance or utility for legal research. The main purpose of ChatGPT is to replicate human language patterns; it is not designed to provide factual information. In contrast, a tool trained specifically for the legal industry is far more likely (though not guaranteed!) to meet basic criteria required by lawyers, such as generating accurate case citations.

Next, consider the system’s strengths and limitations as they relate to the three layers of an AI-driven tool. How do we begin to assess an AI-driven research tool, if so much is hidden or obscured? Understanding all three layers really comes down to a question of information and information literacy: What are the strengths and limitations of the information that is being used as the input for the tool? How is the machine analysing that information, and how much control do you as the researcher have to modify that approach? What gaps or issues are present in the output, and what do they tell you about how this tool operates? Information literacy is at the heart of all these questions. Developing your information literacy skills will not only give you the advantage on assessing traditional legal research tools and databases but will also help you interact with these new legal research tools in useful and meaningful ways.

The following questions provide a starting point for thinking about each of these layers.

Input Layer:

- What dataset underlies this tool?

- What is the breadth of the dataset? (e.g. jurisdiction, types of resources)

- How current is the data?

- What types of human bias exist in the dataset? (e.g. inaccuracies, omissions, systemic bias)

- How could these types of bias manifest in the output?

Analysis Layer:

- What factors are being considered?

- What kind of bias could exist in the algorithm(s)?

- How transparent is the system?

- Does the tool tell or show you how the input is analysed?

- Do you have the ability to control how the input is analysed?

Output Layer:

- How does the algorithm receive feedback on the relevance of the output?

- Does the user have the ability to help “train” the tool?

- What kind of bias could have been introduced by humans involved in “training” the model?

- What kind of bias is reflected in the output?

- What is missing from your results?

Once you have collected as much information as possible, you will be in a place where you can consider how this tool will fit into your research process for this task. Will it help or hinder your legal research process? What are its limitations and how will you overcome them through additional research strategies or using other research tools? How will you conduct a quality check on the information that this system retrieves to ensure that you are presenting accurate research findings?

The answer to whether or not to use an AI system will likely not be clear, and may differ depending on the legal research task you are trying to accomplish. The most important outcome of this process is for you to use a new tool responsibly, effectively, and within its limitations so that you can feel confident in whatever research product you create.

- Gary Marchionini, “Foreword” in Chirag Shah, Collaborative Information Seeking: The Art and Science of Making the Whole Greater than the Sum of All (Berlin: Springer Berlin Heidelberg, 2012) at vii. ↵

- Association of College & Research Libraries, Framework for Information Literacy for Higher Education (American Library Association, 2016), online: <https://www.ala.org/acrl/standards/ilframework>. ↵

- American Association of Law Libraries, Principles and Standards for Legal Research Competency (American Association of Law Libraries, 2020), online <https://www.aallnet.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/AALL2020-PrinciplesStandardsLegalResearchCompetencyFull.pdf>. ↵

- CC Kuhlthau & SL Tama, “Information Search Process of Lawyers: a call for ’Just for Me’ Information Services” (2001) 57:1 J Documentation 25 at 26. ↵

- For example, the authors conducted an analysis of the LexisNexis Canada online bookstore in March 2023. Out of 1,148 available titles, only 52 were classified as available in ebook format (including 38 that were available as PDFs). ↵

- To use your preferred search engine most effectively, consider finding and reading the search documentation for that engine. For example, for Google, see: “Google Search Essentials” (last visited 12 June 2023), online: <developers.google.com/search/docs/essentials>. While Google, Alphabet Inc’s proprietary search engine, is the most widely used, this tip also applies to other search engines such as Bing, Yahoo!, DuckDuckGo, etc. ↵

- The saying “If you aren’t paying for the product, you are the product” is a pithy truism sometimes attributed to entrepreneur and Netscape co-founder Marc Andreessen and popularized in the 2020 Netflix documentary, The Social Dilemma. Google and other online functions earn their billions by attracting and disseminating paid advertising to users based on their recorded search histories. ↵

- “In order to minimize the negative impact of such transparency on the privacy of those involved in cases leading to judicial decisions, CanLII does not permit its case law collections to be indexed by external search engines.” CanLII, “Privacy Policy” (last visited 22 June 2023), s 19, online: <www.canlii.org/en/info/privacy.html>. ↵

- Standardization here refers to the fact that every record in the database has the same fields — simply, boxes into which relevant information can be stored and then displayed in response to a search. For example, in a full-text case law database, every record has a field for style of cause. This field can be searched by a user to discover various cases based on words contained in the style of cause. ↵

- For example, vLex has grown in popularity in recent years and is now available to many lawyers through their local courthouse library. Other jurisdictions have a more competitive landscape for legal services. For example, Google Scholar could be considered an American legal research service since it provides access to multiple case law databases for both federal and state courts. ↵

- Ken Fox, “4 Questions to Ask About Any Database (Part 1)” Slaw (15 December 2016), online: <tips.slaw.ca/2016/research/4-questions-to-ask-about-any-database-part-1>. ↵

- Susan Nevelow Mart, “Every algorithm has a POV” (2017) 22:1 AALL Spectrum 40. ↵

- Ibid at 44. ↵

- Although some algorithms are now sophisticated enough to imagine synonyms and suggest “relevant” content without prompting from a user, the main algorithmic approach used in the three Canadian legal research services is to use the search terms provided. ↵

- This currently is possible by clicking on “Display results using a Boolean Terms & Connectors search”. Look for clues like this to determine if a database has switched the type of search you thought you were running. ↵

- E.g. LexisNexis, “Search Types”, online: <help.lexisnexis.com/Flare/lexispluscanada/CA/en_CA/Content/reference/searchtypes_ref.htm>. ↵

- CanLII, “Search”, online: <canlii.org/en/info/search.html>. ↵

- See Bob Ambrogi, “LexisNexis Enters the Generative AI Fray with Limited Release of New Lexis+ AI, Using GPT and other LLMs” (4 May 2023), online: <www.lawnext.com/2023/05/lexisnexis-enters-the-generative-ai-fray-with-limited-release-of-new-lexis-ai-using-gpt-and-other-llms.html>; Bob Ambrogi, “Thomson Reuters Previews Its Plans for Generative AI, Announces Integration with Microsoft 365 Copilot” (23 May 2023), online: <www.lawnext.com/2023/05/thomson-reuters-previews-its-plans-for-generative-ai-announces-integration-with-microsoft-365-copilot.html>. ↵

- Long Ouyang et al, “Training language models to follow instructions with human feedback” (delivered at the 36th Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems, 2022), online: <proceedings.neurips.cc/paper_files/paper/2022/file/b1efde53be364a73914f58805a001731-Paper-Conference.pdf>. ↵

- Linda Skitka, Kathleen Mosier & Mark Burdick, “Does automation bias decision-making?” (1999) 51 Intl J Human-Computer Studies 991. ↵

- Pierre-Paul Lemyre, “Lexum’s Approach to Automatic Classification of Case Law: From Statistics to Machine Learning” (8 April 2022), online: <lexum.com/en/blog/lexums-approach-to-automatic-classification-of-case-law-from-statistics-to-machine-learning/>. ↵

- Sara Merken, “New York lawyers sanctioned for using fake ChatGPT cases in legal brief”, Reuters (26 June 2023), online: <reuters.com/legal/new-york-lawyers-sanctioned-using-fake-chatgpt-cases-legal-brief-2023-06-22/>. ↵

- For example, predictive tools often focus on a very specific legal question where the courts have determined a fairly set number of factors to consider, such as: is an individual considered to be an employee or contractor under employment law? ↵

- Harry Surden, “Artificial Intelligence and Law: An Overview” (2018) 35:4 Ga St UL Rev 1305. ↵

- Julia Angwin et al, “Machine Bias”, ProPublica (23 May 2016), online: <propublica.org/article/machine-bias-risk-assessments-in-criminal-sentencing>. ↵

- See e.g. Kim P Nayyer, Marcelo Rodriguez & Sarah A Sutherland, “Artificial Intelligence & Implicit Bias: With Great Power Comes Great Responsibility” (2020) AALL Spectrum (May/June 2020) 14. ↵

- For example, a plausible suggested use for AI is for the purpose of identifying the most common or prevalent interpretation of contractual phrases; see David A Hoffman & Yonathan A Arbel, “Generative interpretation” NYUL Rev [forthcoming in 2024], online: <papers.ssrn.com/abstract=4526219>. ↵

- Mata v Avianca, Inc, 2023 WL 4114965 (SD NY). The court found that the lawyers involved acted with bad faith by not reading the cases that were cited in their affidavit and then later swearing to the truth of its contents. A penalty of $5,000 was ordered. ↵

The set of abilities a legal researcher must develop, including the ability to successfully find, assess, use, and apply information regardless of format, access point, or paradigm. Information literacy addresses the characteristics of information itself — its source, its precursor documents, how it is accessed and indexed — and focuses on where, how, when, and why to find that information, rather than how to use a specific database, search engine, or research tool.

Any behaviour or activity the goal of which is to locate or obtain information. In legal research, it is distinct from the acts of information synthesis and analysis. All three elements taken together — information seeking, synthesis and analysis — are the essential building blocks of legal-problem solving.

Legal information of a particular type, presented in a specific format, identifiable by a citation. Also used to differentiate between categories of sources that share similar features, as in primary sources and secondary sources.

In the context of legal research, something that has value or utility for fulfilling your information-seeking need, such as a case, statute, ebook, journal article, blog entry, newspaper article, etc.

The online point from which you begin research in an online environment, usually a specific URL. Access points include, but are not limited to, a service, a webpage, a standalone database, or a search engine.

A searchable collection of information stored electronically and organized in such a way that information can be searched on various dimensions. Westlaw, Lexis, and CanLII each contain dozens of legal information databases.

A software application powered by an algorithm, which enables users to search across large repositories of information. A search engine selects and returns results based not only on the search terms entered by the user, but also based on other selection criteria built into the algorithm, which are usually not known to the user.

The term is sometimes confused with a web browser, which enables access to online content including search engines (a browser is also a software application, but is stored locally on a user’s computer). For example, Alphabet Inc.’s proprietary browser product is called Chrome; its search engine is called Google.

Primary sources of law include legislation (such as statutes and regulations) and the decisions handed down by courts and administrative tribunals. Primary sources establish and carry the full weight of the law, and as such are the sources you will rely upon in most legal writing.

Sources that provide commentary on the law such as treatises, encyclopedias, and articles. They have two basic functions: they explain the law and point the reader towards the relevant primary sources of law. They should always be consulted at the beginning of the research process.

Secondary source formats that pre-date the online information environment. These formats have long been established in the field of law and legal information and include books, journal articles, treatises, and case comments. (cf non-traditional secondary sources and primary sources)

A category of secondary sources that are published in a less formal, more flexible way, using formats that are easily generated and easily accessible online. For example, legal newsletters, blogs, social media, and podcasts.

As a noun, a list that records words, concepts, and/or phrases as they appear in a resource, or that summarizes the features or content of a resource, to facilitate a user’s ability to locate information. E.g. the index found at the back of a book or a journal index.

As a verb, the act of organizing and storing words, concepts, or phrases in an index. E.g. a search engine indexes words on webpages; a journal index indexes the bibliographic information that identifies journal articles.

The past participle, indexed, indicates the state of being included in an index. Understanding where certain types of resources — like legislation or case law — are indexed online impacts the choices you make for researching those resources.