Towards a Theory of Academic Resourcefulness

All of these various influences and insights (and this was a decidedly unexhaustive list) make for an eclectic foundation for learning strategy work. That can be a virtue in itself since it allows for a broad openness to our disciplinary orientations. But it can also be a virtue to establish a more coherent foundation, or set of principles upon which we can more precisely ground and guide the work. That necessarily begins with an attempt at theory-building or model-making which I step very lightly into here, postulating “Academic Resourcefulness” (AR) as the relevant construct to direct the work.

When we stop to consider why we do learning strategy work (and we should, often), we arrive principally at one reason: we do it to help students achieve academic success (that notion of “achievement” alluded to earlier). This, of course, begs the further question: what do we mean by “success” – and this is where the horizons expand. Traditionally, success in this regard meant the attainment of various higher education credentials (grades, credits, diplomas, degrees, etc.), and satisfying standards of excellence in doing so. With that restricted goal in mind, learning strategy work had a narrowly defined focus – give students tools and strategies to optimize their approach to effective study, and determine ourselves successful in this work when students, aided by these tools and strategies, acquire their credentials. In recent years, the idea of success has broadened in three important ways, rightly or wrongly: first, we have recognized that academic “success” is a thing to be defined, not strictly by us and the institution, but by students themselves. Naturally, this expands the idea of “success” considerably. Secondly, we also recognize that the relentless pursuit and attainment of academic credentials can come at a cost to students’ health and well-being, so “success” includes the idea of integrating healthy approaches to study and learning. Thirdly, there is broader acknowledgement that the paths to academic success (however it is defined) are unequally strewn with barriers and this complicates the idea that there is an equal opportunity for all.

These broadened dimensions to the notion of “academic success” have, accordingly, led to a less-precise way of articulating the focus of learning strategy work and its purview. It has become more difficult to distinguish learning strategy work from other kinds of student support, the boundaries are more blurred between academic skill development, mental health support, accessibility, identity development etc. The prevailing mantra about a “whole student approach” makes it increasingly difficult to compartmentalize our work into narrow fields and tight boundaries – students’ encounters with academic life and the deep complexities of learning in institutions of higher education are full, and rich, and complicated. And there is the further complication and contradiction between this “whole student” approach and the highly structured nature of institutions of higher education where bureaucratic compartmentalization of services is the norm. In all of this, the WHY of learning strategy work becomes harder to locate with precision, since the demonstrations of our positive impact become much more expansive. It behooves us, though, to work hard at this, to ground our work in foundational principles of purpose so we can be guided by that in the complexities. Models, frameworks, theories are obviously helpful in this regard, but the field of learning strategy work is not yet firmly rooted by that. As I said, this is, in some respects, its virtue, since we are not bound by especially narrow conceptions of the work, but it also leaves us a bit rudderless and makes our work difficult to explain to others. Therefore, we need foundational frameworks that provide direction without being overly prescriptive. Into this space, I would insert Academic Resourcefulness, as a promising start as it satisfies these two criteria (providing direction while avoiding prescription) and offers a solid foundation for our work. I would define Academic Resourcefulness this way: the capacity to identify, use, and advocate for resources that support an effective approach to study and learning.

Let me back up first, to an earlier effort to develop a framework of student success.

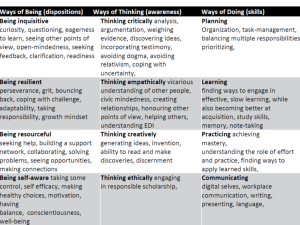

A typical approach to capturing our intentions as “wholistic” educators, is to develop prescriptions, textbook accounts of “how to succeed in university”. And that approach begins with…molecules, building from constituent elements, standalone “modules”, a fulsome apparatus for student success. The standard topics for this are recognizable to the reader, identified through an iterative process of research and discussion among professional educators and the scholarship they produce on the subject. Through this process, an assemblage of topics is organized. My version went something like this: Student success is divided into three primary categories, what I call Ways of Being (dispositions), Ways of Thinking (cognitive awareness), and Ways of Doing (skills). And within each of those categories, I name four main themes of student success that can be explored for the finer and more complex details (see Table 1 below).

Table 1. Proposed Student Success Framework

The literature on student-success is rife with similar reductionist contrivances, students, inundated, the market saturated, with these text-book approaches to post-secondary preparation. Chapter by chapter, students are given the black and white recipe for success. While this is no doubt helpful to students making the transition to and through post-secondary education, it belies something of the complexity and ambiguity of it all. Responsibly preparing students for a good and meaningful educational experience should, in my opinion, never be the banal application of a recipe. Learning is paradoxical and I see this, not as something to be resolved, but embraced. While certainly there is strong body of evidence that highlights a number of factors emerging again and again as important for student success, there is ample room for interpretation of those factors, what they actually mean, their complexity when viewed as a whole, and the ways in which students can fruitfully turn their attention to them. Text-book prescriptions for success fail to accommodate this complexity. Besides, I feel strongly that yet another addition to this molecular, modular approach would add very little that is new or interesting to the world. Students are already amply supplied with the prescriptive lists of “necessary skills”, the stuff, by virtue of its ability to be measured and quantified, so favoured by a narrow, learning-outcomes approach to curriculum design.

How one conceives of these frameworks is important. To me, they are thinking exercises, not blueprints. Again, the traditional approach to building programming from such frameworks is to treat each of these themes independently as a series of “modules” according to the traditional tenets of linear, prescriptive instructional design. But our work is more music than science and a more “artistic” approach to applying these frameworks to student lives better acknowledges some of the ambiguity and complexity and helps students move beyond the simple encounter with lists towards deeper inquiry, to scrutinize the contours of these themes, wrestle with them, problematize them, and question them. Frameworks should be employed for their heuristic value – broad and loose, open to all kinds of interpretation, allowing for the kind of penetrating exploration without being boxed in too tightly. The categories are there to simply bring a modicum of order to a complex set of ideas, a way to proceed through the thicket of educational thinking and student experience. Learning Strategy work is like the playing of the music of those framework compositions, bringing us closer to our philosophical ideal about the complexity and nuance of educational thinking and student experience and our desire, not to flatten or schematize that experience, but to simply better understand it. Frameworks define the blacks and whites, so that we can explore the greys.

So, now years later after that original Ways of Being, Ways of Thinking, Ways of Doing framework, I offer something less rigid toward this effort of theory-building, the idea of Academic Resourcefulness. I suggest the beginnings of this Academic Resourcefulness Framework as being grounded by several premises borne out by research, and/or able to be further investigated:

- Academic success is idiosyncratically defined and is a dual responsibility between students and institutions

- The rigors of academics can be a cause or exacerbator of stress for students, and resourceful students recognize the distinction and accept the reality of this

- Excessive stress can have an adverse effect on academic performance and experience, and resourceful students are better able to mitigate these adverse effects

- Learning is most effective when oriented and motivated by goals and resourcefulness involves self-regulation towards goal-achievement

- Learning can often involve adversity, and resourcefulness can both moderate and be generated from adversity

- Effective learning involves being able to discern between various study tactics and where they best apply

- Belief in one’s ability to manage adversity positively correlates to achievement and resourcefulness, and help-seeking is a feature of this self-efficacy

- Resourcefulness is a capacity that can be learned and learning strategy “interventions” can facilitate and hasten that learning

Further, there are several strands of thought that can be usefully encompassed by the umbrella concept of academic resourcefulness, including self-efficacy (Albert Bandura), Resilience (Michael Ungar), Growth Mindset (Carol Dweck), and Self-advocacy (David Test et al) – all part of the prevailing scholarly narratives about student learning.

So, what does an academically resourceful student look like? Well, the resourceful student is one who is…full of resources. It is a student who is:

- motivated and oriented by both intrinsic and extrinsic learning goals

- able to regulate adverse effects of stress on learning

- able to identify, locate, and call upon community resources of academic and other supports

- able to move productively through academic adversity and setbacks

- able and willing to hone learning and study skills befitting the rigors of post-secondary education

- able to advocate for what is needed but perhaps missing from their educational experience

- able to pull all of this together into a coherent, confident way of navigating their way through study and learning in higher education.

From our perspective as Learning Strategists, we can view it this way, a model for academic resourcefulness:

ACADEMIC RESOURCEFULNESS = READINESS + SKILLS + BELONGING

Leading to a guiding principle: the Learning Strategist’s job is to nurture in students greater academic resourcefulness by helping them develop stances of readiness for the rigors of learning, an expanded repertoire of effective skills and strategies for learning, and a sense of confidence as legitimate participants in their academic community.

Readiness:

These are not skills, these are learning dispositions, postures, stances, that precede or accompany skills – the “learning spirit” described earlier. Like the athlete who assumes a “ready-stance” before a sporting event, a student can adopt postures of readiness for learning. We can guide them in this by helping them reflect upon and begin articulating their purpose, their goals, their reasons for being here. We can activate some of their prior knowledge about learning, calling forth the skills and strategies that have already served them well, building in them a nascent awareness of the kinds of joys and challenges ahead for them, the attitudes, habits, and approaches that are conducive to success, and the communities of support available to help them.

Skills:

The development of competencies around study, self-regulation, metacognition, task management, executive functioning, planning, etc. is typically considered to be the central domain and bailiwick of learning strategy work. And this is true. The development of increasingly sophisticated study and learning skills befitting the rigors, complexities, and challenges of postsecondary academics is a necessary part of a student’s trajectory. Many will simply develop these on their own through trial and error, or as a natural outcome of continuous practice. But others will discover the benefits of working with Learning Strategists whose specialized expertise in this realm can hasten and optimize this development. Skills matter and, as in other domains, they can be honed in students towards more effective learning and study. It must be added, though, that the often-exclusive focus on this domain neglects the other essential and integral elements of academic resourcefulness (readiness and belonging). Invoking the sports analogy again, imagine training a hockey player in stickhandling, skating, shooting skills but neglecting to help them develop a sense of the game itself. Skills and competencies are, naturally, necessary keys to success, but insufficient.

Belonging:

Finally, we are in a unique position to help students connect meaningfully to their academic community. In their influential book Situated Learning: legitimate peripheral participation, Jean Lave and Etienne Wenger (2020, p. 53) said: Learning involves the whole person; it implies not only a relation to social communities—it implies becoming a full participant, a member, a kind of person. This is something we recognize when we see it – the phenomenon of students, not only participating more fully in their academic work, but feeling like they belong to their academic community, that they are valued and actively participating members. This is a process that begins in the transition into higher-education from…somewhere else. Applying Lave and Wenger’s useful model, students are deemed “legitimate” by virtue of their acceptance into the institution, but their early participation exists as very much peripheral, dabbling on the margins. Through practice and ever-deepening participation over time, students acquire the competencies and the social capital to become more active and full members of their academic community. This is the hope, anyway. So-called Imposter Phenomenon is an oft-cited challenge for many students whose transition into feeling like legitimate participants is especially complex. Many students, for a thousand different reasons, have particular difficulty seeing themselves as legitimate participants, or they may experience barriers in their movement from the periphery and feel perpetually on the margins. Learning strategy work intersects with all of this as we coach students through this complicated process, and we can be catalysts for this transition, to help students not only hone their skills, but also their confidence, attitude and sense of belonging.

This is the beginning of a kind of model for learning strategy work. The hypothesis is that better developed academic resourcefulness, so defined, correlates positively with an engaged, deepened, healthy, effective and more successful academic experience. The relevant variables of AR (readiness, skills, belonging), while difficult to measure in a quantifiable way, can nevertheless be assessed rigorously and creatively in service of testing this hypothesis.