The Language of Assessment

Ok, so now we are grounded in some history and context as we wrestle with our assessment efforts. This is important so we are not operating in a vacuum and can better engage in a balanced, thoughtful approach.

It’s important to note here that when folks talk about assessment in education, they are often referring to the assessment of learning that takes place in classrooms – tests, essays, exams, projects etc. The things that get “marked” and accumulate to show a score on a transcript. There is, of course, a deep rich history of debate and discussion about what constitutes “best practice” in this realm, what constitutes meaningful assessment of student learning in classrooms, what works, what doesn’t, the collisions of authentic assessment with administrative efficiency, the purpose of testing, how to give good feedback on student written work etc. etc. We can draw upon all of that good debate as Learning Strategists contemplating our approach to assessment but there are obvious and important distinctions to make as well.

First, we are typically not offering students for-credit learning experiences as part of official curriculum requirements. This is both a challenge and a liberation – a challenge because assessment of student learning is not mutually seen as a requirement when students interact with us. It is the obvious purpose of our work but not recognized as a requirement in the way that classroom work is. This challenge is also precisely what liberates our work as well.

Second, we are more obviously concerned with “program evaluation” as part of our approach to assessment. When we “assess” we are interested in the ways in which our programs are effective at producing x, y, z for students. Traditionally, in a Student Affairs context, this has led to an emphasis on “student satisfaction” since that is an easy thing to measure. But we have rightly and steadily positioned ourselves as educators, involved in the education of students, not simply the providers of satisfying experiences. So, we have the dual concern of advancing the learning and educational mission for students by assessing whether they are learning things AND evaluating the ways in which our programs facilitate this effectively or not.

So, we draw upon classroom assessment practices and thinking about that, but we also operate in a different context. I feel that it is important that we adopt the best from classroom assessment thinking and, because we are free from the many constraints in that context, try hard to avoid the more impoverished and problematic approaches that have beset the student assessment of learning in classrooms.

So, my goal in this section is to explore some of the common language of “assessment” in the Student Affairs context, in which Learning Strategy work often finds itself situated – the terminology of the field that has so deeply influenced how we move, and what becomes important. Language does that. And there is a common language of assessment now that has taken hold, become the vernacular with its own kind of logic. I think it’s important to look more deeply at that language and unearth some of the implications, where it has become co-opted and trivialized, and commodified, and, in this way, become more fluent.

My general tone appears critical and negative at times, and this comes from my irritation at the general buzzwordiness of education and the tendency to render certain terminology meaningless or banal through overuse and superficiality. But really there is no need to incite too much controversy un-necessarily here – sometimes words and terms are just neutral and useful things. But sometimes they are worthy of a deeper dive to see what may lurk beneath the surface. It makes it more interesting, if nothing else.

Assessment versus Evaluation

This is a tricky one. And it can get unnecessarily bogged down in semantics and definitions. Further confusing things is, again, the obvious overlap that we share with classroom learning but with notable differences. People in academic departments – instructors, chairs, deans – will engage in “assessment” of students as well as “program evaluation”. The distinctions between the two are instructive for our purposes.

Think of assessment as a way to understand and gauge student learning.

Think of evaluation as a way to understand and gauge program effectiveness.

In a geography classroom, for example, instructors will assess the extent to which students have learned the concepts of the class, (I still remember how plate tectonics work). The Chairs and Deans of the geography department will evaluate the geography program (requirements, staffing, curriculum etc.)

It’s a similar thing for us.

The folks running certain learning strategy interventions, programs, events for students will assess the extent to which participants learn something from the experience. And folks will also evaluate the effectiveness of that program for achieving that result (staffing, locations, resources etc.)

I suggest we just keep this simple and just use the word Assessment to refer to both things. When we are assessing in the Learning Strategy domain, we are gauging the extent and nature of student learning (our primary goal) and gauging the effectiveness of our programming to achieve this.

Learning Outcomes

Ok. So we have dispensed with the word Evaluation. So far so good. But what about this thing called Learning Outcomes (LO’s)? This is even more contentious and, I must confess a deep ambivalence at the outset about this concept which I think is worth unearthing before we all blindly and breathlessly accept the idea of learning outcomes as gospel. Bear with me.

First, let’s give a simple explanation of what is typically meant by the term “learning outcome”. From the University of Toronto’s Centre for Teaching Support and Innovation (CTSI): Learning outcomes are statements that describe the knowledge or skills students should acquire by the end of a particular assignment, class, course, or program. This is a traditional, typical description and, as with most treatises on LO’s, the CTSI site goes on to describe the word-cloud of associations and rules and protocols around the use of LO’s – invoking Bloom’s Taxonomy as the foundation, the use of “action verbs” in writing LO’s, being specific and precise, the importance of “mapping” outcomes onto curriculum etc. etc. All of this can easily be regarded as benign, useful and logical. It’s a sensible syllogism after all – articulate what you want students to learn, design the teaching situation towards that end, assess the extent to which the learning outcome has been met, adjust as necessary. Hard to argue with the sensibleness of that. And most good teachers would follow that basic logic in some way. Where things get ugly is in the pervasiveness of the concept as an administrative tool; that is, in contexts far removed from student-teacher interactions, where it makes sense, and into contexts of whole departments or divisions, where it makes much less sense. Describing LO’s across an entire division of, say, Student Affairs, is an exercise in such abstraction that it becomes meaningless as an educational device, and useful only as a managerial device of accountability. The educators beholden to those abstract LO’s, and required to report back on how well their programs are meeting them, either engage superficially with that process (“checking boxes”), or limit themselves creatively for fear of not adhering to the LO plan. This is a critique that can go deep, and it can expose a kind of rift among those who think about their craft as educators and the role they play in the systems of education. It’s not trivial. Many will be easily convinced by the logic of LO’s and get fully on board, while others (a minority, it seems) will see it as a managerial affront to the art and beauty and ambiguities of education. As always, I think there is a sensible middle-ground – a place where the logic of classroom LO’s can be applied, but in ways that acknowledge their limitations and that reject the managerial purposes with which they can be inappropriately used.

Perhaps it is the word “outcome” that is especially problematic. A focus on outcomes fails to observe the importance of opportunity. Imagine that your educational program (“intervention”) reveals disparate outcomes for the students there. Or, worse, simply fails to meet the LO’s you set for the students. Is this because the program was ineffective or is it because the LO’s failed to acknowledge the inputs – the varieties of experience that any grouping of students will embody. A focus on end-game can force a neglect of early game readiness. This is also not trivial.

The Learning Outcomes movement has touched a nerve for many folks and has stirred plenty of debate worth exploring. Consider, Bennett and Brady’s piece titled A Radical Critique of the Learning Outcomes Assessment Movement, published in the 2014 edition of Radical Teacher, or Ian Scott’s The Learning Outcome in Higher Education: Time to Think Again? Published in the 2011 edition of the Worcester Journal of Learning and Teaching. For our purposes, let’s simply be situated in the broader context and use LO’s accordingly, with nuance and understanding, focus on LO’s as helpful signposts, articulations of what we want students to learn in our midst, but avoid the administrative context of LO’s and the impoverished, check-boxy practices they encourage.

Curriculum

I’ve shared my thoughts elsewhere about the perils of a “curricular” approach in Student Affairs (Hannah and Ellis, 2018). It captures something of my thinking about the word curriculum and our often-credulous embrace of this as a method in Student Affairs generally, a cautionary tale about the use of certain approaches that, while seemingly good and sensible on the surface, have a more complex history worth exploring. From that article:

IN THE MARCH 2017 issue of About Campus, student affairs professionals from the University of Delaware, Kathleen G. Kerr, James Tweedy, Keith E. Edwards, and Dillon Kimmel, describe their pedagogical shift from “traditional models” of program development to the so-called “curriculum model” and the ways in which this changed the nature of their work. The authors make the case for a curricular approach in student affairs, suggesting that, if we are to get beyond the “magical thinking” of traditional (i.e., noncurricular) approaches to our work, we need to get serious.

Those authors offer a pretty doctrinaire and, frankly, neurotic sentiment, in my opinion. As always, we can apply a common-sense approach to this. Thinking about a learning skills “curriculum” for students is not a bad idea on its face. On the contrary, it can be a very useful device for thinking through what we want to offer. But, like all tools, it can be misapplied as an apparatus of control and obedience. In my view, looser pedagogical forms that don’t necessarily subscribe to intentionality, structure, and sequencing but, rather, make room for the emergent, the unpredictable, the artistic also need to be in the mix. This looser, craftier approach is not “magical thinking”, it is a deep and honourable form of pedagogy not valued for its efficiency necessarily, but for its substance.

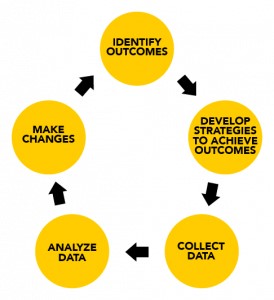

The Assessment Cycle

Many of the concepts just described are captured as a whole in the so-called Assessment Cycle Model – again a seemingly non-controversial, benign, sensible process, but also guilty, in my view, of all the same deficiencies as noted above. There’s not much to add here – the assessment cycle is a straightforward approach to doing a program evaluation and is now a kind of favoured, codified approach in Student Affairs. In short, when conducting any kind of learning assessment or program evaluation, this approach demands adherence to some variation of the following:

A common-sense approach when used wisely. As with the other concepts, it can render assessment efforts a bit void of substance, especially for new practitioners who may yield to it as a kind of instruction manual. The useful analogy for me is imagining the art of painting being reduced to a paint-by-numbers approach – perhaps producing something vivid, but ultimately uncreative. Again, the key is simply to resist slavish adherence to the process because it will blind you to the other creative possibilities – medicine wheel approaches, emergent design approaches, grounded-theory approaches, etc. Be familiar with the assessment cycle, use it judiciously, but do not be held captive by it.

Storytelling

The word “storytelling” has become popular of late. It’s been rendered dumb by overuse, but it’s a good word. For our purposes, it really is a straightforward thing – telling stories as the ultimate purpose of assessment – revealing and telling as much truth as we can from what is inherent in the data we collect. It’s really just a more human, more expansive approach to “reporting” that acknowledges the power (and limitations) of narrative as an explanatory device. Eschewing what have become the platitudes of the day (“storytelling is the basic unit of human understanding”, or “humans are storytelling creatures”) which, while true, is a bit hyperbolic for our purposes, we acknowledge that we are not simply reporting on data, we are attempting to illuminate something of the student experience of learning and study. We look for what is common to that experience but also the varieties of experience that are present. And we give voice to that, in some way, through narrative, through thick description. This is, of course, interpretive, subjective. And we need to be careful about commodifying students’ “data” and testimony for some self-serving purpose; “look how great we are, the students say so”. This will happen to some degree, inevitably – it’s part of the process. And the culture of assessment for accountability will incentivize that. So, we will do our best, we will triangulate and apply mixed-methods with as much rigor as is reasonable, we will acknowledge our biases, and motivations, and we will be honest in our portrayals of students and their experiences. And we will know that this too, despite our best efforts at telling the whole story, will be incomplete.

All of this may come off as cynical and pessimistic about the assessment enterprise. On the contrary – I believe in the enterprise of better understanding our work and seeking and analysing data and feedback to do it ever better. I simply take this critical perspective because I want there to be a basic truthfulness to what we do, something that often gets lost in the fervour of fads that invade our profession sometimes. The logic of learning outcomes and curriculum, and the neat managerial bow of efficiency that the Assessment Cycle expresses is all useful, it’s good. I just want us to remember that they are good and useful especially for certain purposes that rank managerialism and efficiency over other educational priorities. It becomes common-sense to adopt these kinds of “technologies” as undeniably good because they are – for certain purposes. The danger, of course, is that it sweeps from our mind the deeper more complicated questions about those purposes. Did we all agree and come to some consensus about big questions like the purpose of higher education, one that declares a market-driven, competency-based, marketable skills, neoliberal approach to education as the best one? If so, then learning outcomes, curriculum, and assessment cycles are effective tools in that domain. But I think it’s important to not let these shiny technologies dictate or blind us to the deeper debate about the higher purposes of education. The matter is not settled.

So, how can we find a good common middle ground? One that makes use of these effective tools without being so swept up in them that we forget the nuance, the complexities, the mysteries, the un-measurable qualities of an education?

We can get back to some of the deeper, more fundamental reasons for assessment, not just an instrument for specific or even questionable purposes, but as a way to learn more about what we do, discover its value, unearth surprises in the work, and be more equipped to improve – assessment as a way to inquire, with open minds about our work and then tell the stories of what we find.