Insights from Teaching, Instructional, and Learning Design

Learning Strategists are teachers. Unlike other contexts in which teachers find themselves, we have the beautiful virtue of being relatively unbound by narrow curricular requirements or paint-by-number methodologies. This makes a lot of room for the intuitive, the spontaneous, the improvised. That’s all good, but to do this well, we also need to be familiar with and practice the effective design of intentional learning experiences. Think about jazz music. It is the singularly beautiful art of improvisation among highly trained players but within highly structured parameters. So, as always, there is expansive territory to explore here. As mentioned in the previous section, Learning Strategy work does not yet have its own normative theory to ground the work, so it draws instead analogically from a deep, sophisticated, eclectic set of scholarly traditions that we peruse and weave together into our own texture. (I suggest in another section a conception of Academic Resourcefulness as a possible progression towards greater coherence on this front). Regardless, and in keeping with our purposes here, we can pull on some relevant threads of effective design of educational experiences, consider a few starting points – some example models, theories, concepts whose basic premises can be provocations to guide some of your decisions as you design and conduct your learning strategy sessions. This is but a sampling of the possible places we can draw from, so see what resonates with you, ponder where you might want to dig deeper, find out what’s missing or where these further lead you, ask yourself whether these models are relevant, informative, helpful to you or not.

Coaching (Donald Schon):

Basic idea

There are different schools of thought on the idea of “coaching”, but here I briefly touch on the insights of Donald Schon, an influential thinker on professional practice and notions about becoming skillful through doing and reflection. In this way, his insights come to bear on our work in two ways – as practitioners engaged in learning ourselves, and as guides for students doing their own learning.

Schon’s thoughts about coaching follow from his insight that students educate themselves only by first doing what they “…do not yet understand”, and for this process to go especially well, the services of, not precisely a teacher, but a coach, are required. He describes three components of effective coaching: “…setting and solving the substantial problems of performance; tailoring demonstration or description to a student’s particular needs; and creating a relationship conducive to learning” (1987, p. 182). This describes the practice of learning strategy work with students very well, and our approach, while perhaps using different terminology, invokes these three elements. We are attentive to the environment we set, aiming for welcome and hospitality and fitness for learning, we take time to assess the whole student situation in all its relevant detail, and we teach and model and guide towards improvements specific to the student’s situation. He goes on to describe three models of coaching that extend those insights and that can be applied in different situations: He calls these:

- Follow Me – teacher demonstrates something to be emulated

- Joint Experimentation – a collaborative venture, teacher, more knowledgeable, resists solving the problem, but presents possibilities from which student chooses

- Hall of Mirrors – teacher and student reflect together on the ambiguities, seeing together the errors and failures as opportunities for learning

Implications for learning strategy work

The concept of coaching is informed by many disciplines, sports coaching, life coaching, career coaching, etc. Donald Schon’s conception of professional coaching is but one among many that can be drawn upon here – one that I think is especially relevant. The foregoing was an unfairly brief account of his ideas but captured there are two helpful heuristics when working with students as a Learning Strategist.

The first is his three components of effective coaching:

- Setting and solving the substantial problems of performance

- Tailoring demonstration or description to a student’s particular needs

- Creating a relationship conducive to learning

And the second is his three models of coaching:

- Follow Me

- Join Experimentation

- Hall of Mirrors

Think of the “three components” as your prerequisite higher-level goals as a learning coach and the “three models” as the methods at your disposal to meet those goals. Applying these heuristics in your practice will help immeasurably to effectively guide your approach.

Transactional Distance (Michael Moore)

Basic idea

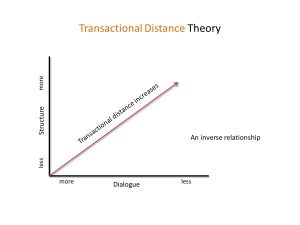

Michael Moore developed this theory in the context of distant learning, or technology-mediated learning at a distance, but it has broad applicability to any learning design. The idea is that there exists, in all intentionally designed learning situations, a psychological “distance” between the teacher and the student, a space or threshold of potential misunderstanding. Learning is better when this distance is minimized. Moore suggests there are three variables in any learning situation that can be manipulated with corresponding effects on this transactional distance: structure, dialogue, and learner autonomy. Each of these variables interact with each other, sometimes in inverse relationship.

Implications for learning strategy work

It is a complex relationship with many things to consider, but generally, in order to reduce distance, the instructional designer aims for maximum dialogue between student and teacher, and since dialogue and structure interact in an inverse relationship, this will mean designing with low structure. Think of one-on-one work with students where conversation is key. These interactions are not highly structured, they are often free-flowing, spontaneous and driven by conversation – low structure, high dialogue. Alternatively, consider a one-hour workshop, or an online resource. In these sessions, there is less room/time for dialogue. It is driven mainly by content and learner autonomy. So, we would design these sessions with more structure, and intentional pacing in mind. And so on. As you contemplate the design of any of your various learning strategy interventions, you can consider these three variables and experiment with their manipulation.

Community of Inquiry (Garrison, Anderson, Archer)

Basic idea

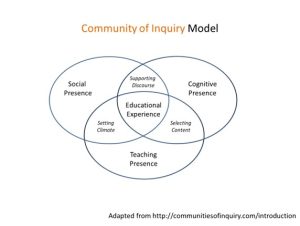

Emerging out of theoretical frameworks underpinning online and distant education, this model asserts that a deep and meaningful educational experience is achieved in community – a group of individual learners who engage together in purposeful meaning-making. There are, according to this model, three features of a productive learning community:

Social presence – “…the ability of participants to identify with the community (e.g., course of study), communicate purposefully in a trusting environment, and develop inter-personal relationships by way of projecting their individual personalities.” (Garrison, 2009)

Teaching Presence – “…the design, facilitation, and direction of cognitive and social processes for the purpose of realizing personally meaningful and educationally worthwhile learning outcomes.” (Anderson, Rourke, Garrison, & Archer, 2001).

Cognitive Presence – “…the extent to which learners are able to construct and confirm meaning through sustained reflection and discourse.” (Garrison, Anderson and Archer, 2001).

See: the Community of Inquiry website for more.

Implications for learning strategy work

Like the aforementioned “transactional distance” model, this framework provides a way to purposefully design engaging learning experiences by ensuring these features are present. The designer can play and experiment with these variables: social presence – ensuring that the spaces of learning are welcoming, showing up with honesty and authenticity, facilitating conversations that are real; teaching presence – ensuring, in whatever ways are appropriate to the situation, that there is meaningful, engaging, relevant subject-matter, ideas, and content around which learning can be oriented and cohered; cognitive presence – ensuring that there are built-in opportunities for reflection upon learning, time and space and prompting of students to question, confirm, critique, adapt, assimilate, construct new and evolving insights.

The Medicine Wheel for Learning (Michael Thrasher)

Basic idea

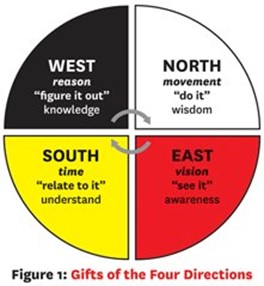

Many of the time-honoured Indigenous approaches to teaching and knowing and learning are very much in rhyme with a learning strategist pedagogy, so these approaches are, or should be a natural part of that canon. Two complementary concepts in particular that are integral to Indigenous approaches to learning – relationality and wholeness – get expressed especially well through medicine wheel imagery and structure. Consider the adaptation of Cree elder, Michael Thrasher’s medicine wheel of learning (shown above) as one such conception – one that centers the natural seasonal round and the “gifts of the four directions”. In contrast to more linear imagery often associated with western conceptions of education, the wheel, partitioned into “gifts” of four parts, captures more ideally this complex complementarity – discreteness and wholeness at once. And these gifts of four offer multiple ways to consider the learning process. For example – attending to the four dimensions of a student’s learning – emotional, spiritual, cognitive, and physical, or moving students through a four-phase cyclical pattern of learning – awareness, understanding, knowledge, and wisdom. And these threads of four can be braided to many other four-part “systems” – the four elements, the four directions, stages of life, seasonal cycles – making for complex inter-relationships – distinct threads but also inseparable – a complex idea that can be brought to bear on teaching and learning situations.

Implications for learning strategy work

We should be mindful here of flattening the potential complexities of this through over-simplification or misconstrual. But as a simple start, we can imagine our program/instructional design being informed by this approach, one that moves students through a kind of 4-phase, cyclical pattern of learning in any context, with any subject-matter: awareness, understanding, knowledge, and wisdom. That, of course, is wide-open to interpretation, but encourages a more thoughtful, more deliberate, more attentive and appropriately paced learning situation. Similarly, as a teaching and learning design heuristic, ensuring somehow that there is attention given to all dimensions of students’ being – emotions, cognition, spirit, and physicality. Attending to these things deliberately and thoughtfully – the inter-relatedness and wholeness of things – will enrich the learning situation.

Community of Practice (Lave and Wenger)

Basic idea

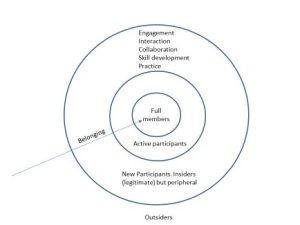

Community of Practice, as elaborated by Jean Lave and Etienne Wenger, is not strictly an “instructional design” framework but I do think it can be usefully construed that way for the design of learning strategy work. The idea emerges as a more bounded version of social learning theory and posits that, particularly in this age of information and networks, humans engaged in learning will benefit from communities of others with a common concern or interest. Described in this way, it seems obvious and self-evident, but it contains some fundamental ideas. Briefly, a true community of practice, according to Lave and Wenger, includes three elements

- A domain – the subject matter, shared area of concern or interest

- A community – a group, brought together by their shared interest who meaningfully interact, share ideas, and develop relationships over time that centre on that shared interest

- A practice – a common profession, or vocation, or occupation among the participants such that they can engage in building shared resources and build their practitioner repertoires

Implications for learning strategy work

Some of the work of Learning Strategists will involve or overlap with the idea of cultivating communities. There will be extended, cohort-like programming or learning groups that will have this as a foundational principle. So, the community-of-practice idea can be informative. The domain, or shared interest, generally, will be “study and learning” but it can be more specific (writing, productivity, well-being etc.). Your job will be to better define that domain, then invite student participants to be in that “community” (which, by necessity, needs time to evolve), and facilitate a process by which they can share and reflect together, thus building their student repertoire. This is a different endeavour than delivering “workshops” or other information-transmission events. This is ongoing work that requires time, patience, care, improvisation, invitations to different kinds of participation, space-making, dialogue, spontaneity, adaptation, tolerance for messiness etc. All well worth the effort, because students often learn most deeply in communities of their peers.

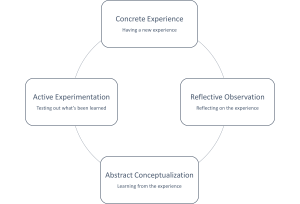

Experiential Learning Cycle (David Kolb)

Basic idea

Few instructional design ideas have had more influence in the co-curricular spaces often occupied by Learning Strategists than David Kolb’s Experiential Learning Cycle. Part of its appeal is its elegant reduction of a complex idea of learning into a simple four-part cycle. As with so many educational models that seek to bring simplicity to complexity, this is also its weakness. Kolb’s model is founded on the idea that meaningful learning happens when we “transform experience”. He proposes a four-part process whereby this happens:

- Concrete experience – learning begins in an encounter with the world, an experience in which the student is actively engaged or implicated.

- Reflective observation – experiences are followed by reflection, a process of looking back upon, asking questions about, discussing with others, comparing, analyzing. It is a process of trying to make some greater sense of the original experience.

- Abstract conceptualization – that continuous reflection will lead students to a deeper understanding of the original experience, its implication and meanings. This can involve a disruption of previously held ideas, or transformations in thinking, and the possibility of applying those new conceptions to other real-world situations.

- Active experimentation – finally, or in perpetual cycle, the student will extend and apply those reflections to subsequent experiences, try out new ways of encountering and engaging in those experiences based on the newly acquired insights.

Quite simply, this cycle can be applied in the design of workshops or other learning strategy programming as “experiential learning” opportunities – that is, by facilitating a process by which students learn-by-doing. One can imagine a four-part series for students, each part embodying a phase of Kolb’s cycle. Or a single session divided into four parts. Students can be provided with a “concrete experience” in the session itself, or be asked to reflect upon one from their actual academic experience. Student peers can be usefully employed as supporters in these sessions, to facilitate discussion and model the experiential cycle of reflection. As a kind of rubric for designing an instructional or learning session, this can be an especially helpful model, with the usual caveat that it not be imposed without nuance and room to breathe.

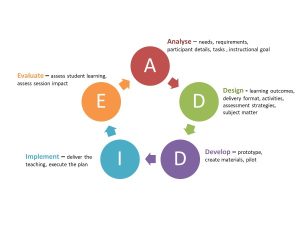

Traditional ADDIE Instructional Design

Basic idea

This is about as traditional and structured as it gets in the world of instructional design (the ADDIE model was developed by the US army, after all). This model is very widely used, particularly in the corporate training world where its structured procedure is easy to implement and favoured by folks who prefer a linear approach. It has influenced other similar models with slightly different emphases (Successive Approximation Model (SAM), Attention-Relevance-Confidence-Satisfaction Model (ARCS), or even the Design Thinking Model, and many others (educators and trainers love models). ADDIE can be a great tool for beginning a program design process. It stands for:

Analyse – understand the student audience, set the appropriate goals for them

Design – conceive of the necessary elements of instruction, media, dialogue, activities,

assessment etc.

Develop – put the above ideas into production, pilot the project, experiment and evaluate what works

Implement – ongoing process of updating, revising, tweaking, optimizing the program design

Evaluate – assess the degree to which the original learning goals have been met

Implications for learning strategy work

Straightforward, really. The ADDIE model (or other similarly conceived alternative) can be a way to approach the planning and design of a learning program. I would suggest that it lends itself best to a learning series, or an extended program of some kind where more careful, upfront planning is more critical. My word of caution here, is that, while the model may lend itself especially well to “training” where information transmission is central, it may prove overly structured in some of the contexts of learning strategy work where outcomes are more fluid and emergent. Still, it can act as a good planning tool, or a place to start.

Conditions of Learning (Robert Gagne)

Basic idea

This “model” is less focused on instructional design and more on effective instruction once in “the classroom” with students. Robert Gagne suggests nine events in the sequence of effective instruction and the corresponding student thinking processes at each event:

- Gaining attention (reception)

- Informing learners of the objective (expectancy)

- Stimulating recall of prior learning (retrieval)

- Presenting the stimulus (selective perception)

- Providing learning guidance (semantic encoding)

- Eliciting performance (responding)

- Providing feedback (reinforcement)

- Assessing performance (retrieval)

- Enhancing retention and transfer (generalization).

Learning Strategists often find themselves in the role of teacher, tasked with the provision of well-considered, guided learning and instructional experiences for students. This is intuitive business, it’s complex business. And that’s all ok. An insistence on neatness in what is inevitably a messy situation is never good teaching. But, it needn’t be a complete improvisation either – it can be guided by what we know to be effective in the learning and teaching moment. The application of Gagne’s nine-events can be a useful application in this regard, a kind of menu to which you can refer in the design and execution of your lesson plan.

First People’s Principles of Learning

Basic idea

In the early 2000’s, the First Nations Education Steering Committee in British Columbia developed the First People’s Principles of Learning for the BC Ministry of Education, so that it could be embedded as a framework into K-12 teaching. They were developed by and advisory committee made up of Indigenous Elders, scholars and knowledge keepers as a way to authentically embody important aspects of Indigenous pedagogy.

The Principles are as follows:

- Learning ultimately supports the well-being of the self, the family, the community, the land, the spirits, and the ancestors.

- Learning is holistic, reflexive, reflective, experiential, and relational (focused on connectedness, on reciprocal relationships, and a sense of place).

- Learning involves recognizing the consequences of one‘s actions.

- Learning involves generational roles and responsibilities.

- earning recognizes the role of Indigenous knowledge.

- Learning is embedded in memory, history, and story.

- Learning involves patience and time.

- Learning requires exploration of one‘s identity.

- Learning involves recognizing that some knowledge is sacred and only shared with permission and/or in certain situations.

Again, this provides another useful set of ideas for an educator designing and guiding educational experiences, one that draws upon a deep and rich Indigenous tradition of pedagogy, and focuses your attention on the more humane, ethical, holistic responsibilities of the educator, and the transcendent features of teaching and learning experiences. These principles represent a set of commonly shared ideas amongst Indigenous people, but it’s, of course, important to also recognize that it does not capture the full reality of variation and complexity amongst Indigenous people. Reflection upon and adoption of this framework in your own teaching can be an act of reconciliation, if it is accompanied by the appropriate acknowledgements about where it comes from.