2.1 What is a “Lawyer” and how are Lawyers Licensed?

Gemma Smyth and Andrew Pace

What is a “Lawyer” and how are Lawyers Licensed?

The conditions under which people are permitted to call themselves a lawyer varies around the world. In common law Canada, students typically must complete or substantially complete an undergraduate degree, gain entry to a law school accredited by the Federation of Law Societies of Canada, complete a three year degree, then enter a licensing process. Most lawyers in Canada receive a license by going to a Canadian law school. Other lawyers get their training in another country and come to Canada as “NCA Candidates” (National Committee on Accreditation), which is another pathway to licensure. Both Lakehead and Toronto Metropolitan University’s law schools have “Integrated Practice Curricula” in which law students meet both experiential learning competencies and the Federation education requirements in three years. Students are therefore not required to article. It is likely that other pathways to licensure will arise in the coming years.

Keep in mind that lawyers in Canada still receive their licenses in each province or territory separately. Just because a lawyer can practice in Ontario does not mean they can practice in another Canadian jurisdiction. There are various mobility agreements (basically, agreements to practice either temporarily or permanently in another jurisdiction) governing whether and how lawyers can practice in another province or territory.

Because law is a self-governing and self-regulating profession, licensing is regulated by each provincial and territorial law society. Most provinces require students to engage in some sort of practical training program and a set of exams. At the moment, the Law Society of Ontario requires students to complete two written, 100% exams (the barrister and solicitor exams). This is different from other provinces such as Alberta, Manitoba, Saskatchewan, and Nova Scotia where students all take a series of courses offered by “CPLED” (Canadian Centre for Professional Legal Education). In British Columbia, students must complete the twelve month Law Society Admission Program (nine months of articles, a ten week Professional Legal Training Course, and two qualification examinations). There are more specifics about the legislation and other rules governing lawyers and law practice in section 3.3.

In Canada, students must “article” – essentially, work in a legal workplace under the supervision of a licensed lawyer and meet a set of articling competencies. Articling is not a requirement in the United States. This has significant impacts on legal education, law practice and lawyers’ careers. Upon licensure, lawyers can essentially practice in any area of law they wish. Lawyers are also subject to continuing education requirements which vary across Canada.

The complete pathway to licensure in Ontario for most law students is:

- hold a bachelor’s degree (although there are some exceptions to this rule),

- complete three years at a Federation accredited law school in Canada,

- pass a Bar exam (in Ontario, this consists of two 100% multiple choice exams),

- complete a licensing application, including a “good character” assessment

- complete a period of articling (“experiential training”, with the exception of students who have completed the Integrated Practice Curriculum, or are enrolled in the Law Practice Program), and,

- take an Oath (typically at a Call to the Bar ceremony).

Students will have been introduced to the concept of the “solicitor-client relationship” – the protected relationship between a lawyer and client. This relationship is at the core of a lawyer’s professional identity.

What lawyers are required to know, do, and value in order to gain and maintain licensure has been hotly debated, especially in Canada where there is no distinction between a solicitor and barrister. Essentially, when a lawyer is called to the Bar they are licensed to practice in any legal area. This has lead to serious questions at the regulatory level regarding competence to practice.

What licensing will look like in the future is also unclear (see, for example, http://www.slaw.ca/2018/07/27/bridges-over-the-chasm-licensing-design-and-the-abolition-of-articling/). There are active conversations regarding whether to retain articling as part of licensure at all. There are many immediate implications for clinical and experiential learning programs, one of which is whether these programs will be required to meet the articling competencies (also called “Experiential Learning Competencies”). Also noteworthy, American states that do not currently have a practice requirement pre-licensure are debating programs similar to articling!

Despite the fact that lawyers are called to the bar and licensed to practice law does not mean learning is over. In fact, lawyers require learning throughout their entire careers, typically referred to as “Continuing Professional Development” (CPD).

The Role of Continuing Professional Development (CPD)

As a lawyer, education does not stop after a law degree and articles. All Law Societies require Continuing Professional Development (CPD). The particular CPD requirements of each province are different. This section focuses on Ontario.

Why are lawyers required to complete CPD hours?

While a few disparaging comments might be made about CPD requirements, most lawyers find CPD extremely helpful to maintain competence in practice. The law, policy and approaches to law practice and practice management are constantly changing. CPD can be an efficient way to keep up with these changes and connect with colleagues in similar practice areas. According to the Law Society of Ontario (“LSO”), CPD hours are intended to “maintain and enhance” the competence of practicing lawyers. CPD hours help ensure practicing lawyers are up-to-date with relevant changes in their profession which therefore contributes to the quality of services provided to the public. Lawyers who have been deemed by the LSO as “certified specialists” in their practice areas are also required to complete 10 additional hours in their area of expertise along with the 12 hours expected of practitioners generally, ensuring they maintain the level of competence associated with such a designation.

What is an “eligible educational activity”?

The LSO recognizes two different types of educational activities for the purposes of CPD hours: CPD programming and alternate educational activities. CPD programming is delivered in a formalized manner by expert practitioners and other professionals; usually either in-person or online.[5] Alternate educational activities permitted to count for CPD hours include teaching (for a maximum of six hours per year), writing/editing (for a maximum of six hours per year) and mentoring (for a maximum of 12 hours per year).[6]

Within their 12 hour requirement, lawyers must complete a minimum of 3 Professionalism Hours. These are CPD sessions on topics related to professional responsibility, ethics and practice management.[7] Since 2018, lawyers have been required to complete 1 Professionalism Hour with programming that addresses equity, diversity and inclusion (“EDI”) issues; this hour counts towards the three hour yearly total required.

Professionalism Hours, including the EDI requirement, will only count toward CPD if the programming was accredited by the Law Society of Ontario. Lawyers can complete Professionalism Hours and subsequently apply to have them accredited, but they run the risk of their hours not being accepted as sufficient.[8] The remaining nine hours of CPD required each year can be completed without accreditation, as long as they address substantive or procedural law topics.[9]

What is the cost of yearly CPD hours?

Cost of CPD programming varies based on a number of factors including practice area, delivery method and length. Since the Coronavirus pandemic, virtual offerings have increased and are often saved online for later viewing (at a fee). The LSO store has a combination of live and replay options, all of which count for CPD hours. One to two hour sessions can cost anywhere from $150.00 and up, where half-day sessions start around $250.00. Provincial summits run typically run for multiple days and participants will be expected to pay for a ticket to the entire event, which typically starts around $500.00. In many cases, all CPD hour requirements can be completed after attending one of these summits.

As a young lawyer, what CPD should I prioritize?

There are a number of CPD sessions created specifically for new calls. The Ontario Bar Association’s Young Lawyers Division is an online community where resources for new lawyers are pooled, including available CPD programming. There are a few general categories of CPD programming:

- Interpersonal, Client-Facing Skills in the Legal Profession

Aside from the substantive law taught in law schools, much of the practice of law involves dealing with people. The Young Lawyers division of the OBA has designed programming specifically for navigating relationships with a variety of different individuals and groups, including clients, opposing counsel, the bench and firm supervisors. Their yearly series dubbed “Call Forward: A Series for Students at Law” provides a crash course on what is needed to bridge the gap from student to young lawyer including practical advice on career trajectories. There are also course offerings from in-house counsel and sole practitioners regarding emotional intelligence and building a book of business.

2. The “Six Minute Lawyer” Series

The “six minute lawyer” series is designed to be a concise, clear roundup of important updates to specific areas of law. Courses are taught by advanced practitioners in their respective areas who research, summarize and present key findings for the practicing lawyer in 2024. Areas of practice typically include criminal, family, employment, estates, and others.[15]

3. From the Bench

As a young lawyer interested in litigation, there is a steep learning curve to overcome. Young lawyers can hear directly from presiding judges about best practices in the courtroom. CPD sessions such as the “Tips from the Bench” series are conducted by Superior Court justices and cover how to appropriately address the court in a variety of different scenarios.

What is “self regulation”?

Students will have heard that the legal profession is “self regulated” or “self governing”. Each Law Society derives its authority from a piece of legislation – usually a Law Society Act of some kind (eg, in Alberta, the Legal Profession Act). In Ontario, the Law Society of Ontario (until surprisingly recently called the Law Society of Upper Canada) was created by a piece of legislation. This legislation gives the LSO the power to regulate, license and discipline its members. The Law Society Act and the Rules, Regulations and Guidelines set out how this happens.

Self-regulated professions are required to govern themselves in a manner that serves the “public interest”. There are many ongoing debates about whether lawyers should continue to be able to self-govern.

Law Societies have boards of directors. Directors are called “benchers”. Benchers are elected by their peers (other lawyers and, in Ontario, paralegals). Benchers are lawyers, paralegals and lay people. They have (usually) monthly meetings called “Convocation”. During these meetings, they make decisions about policy and other matters. The Chair of Convocation is called the “Treasurer”.

In Ontario, paralegals are also regulated by the LSO. This is not the case in other provinces and territories. There are many ongoing debates about which services paralegals should be licensed to provide and which should be solely the purview of lawyers.

At the Call to the Bar in Ontario, licensees swear the following oath:

“I accept the honour and privilege, duty and responsibility of practising law as a barrister and solicitor in the Province of Ontario. I shall protect and defend the rights and interests of such persons as may employ me. I shall conduct all cases faithfully and to the best of my ability. I shall neglect no one’s interest and shall faithfully serve and diligently represent the best interests of my client. I shall not refuse causes of complaint reasonably founded, nor shall I promote suits upon frivolous pretences. I shall not pervert the law to favor or prejudice any one, but in all things I shall conduct myself honestly and with integrity and civility. I shall seek to ensure access to justice and access to legal services. I shall seek to improve the administration of justice. I shall champion the rule of law and safeguard the rights and freedoms of all persons. I shall strictly observe and uphold the ethical standards that govern my profession. All this I do swear or affirm to observe and perform to the best of my knowledge and ability.”

Reflection Questions

- The above Oath is sworn by all licensees at the Call to the Bar ceremony. What values do you see reflected here? What might be missing?

- What is important to you about being called to the bar and practicing law? If you were asked to write your own Oath, what might it look like?

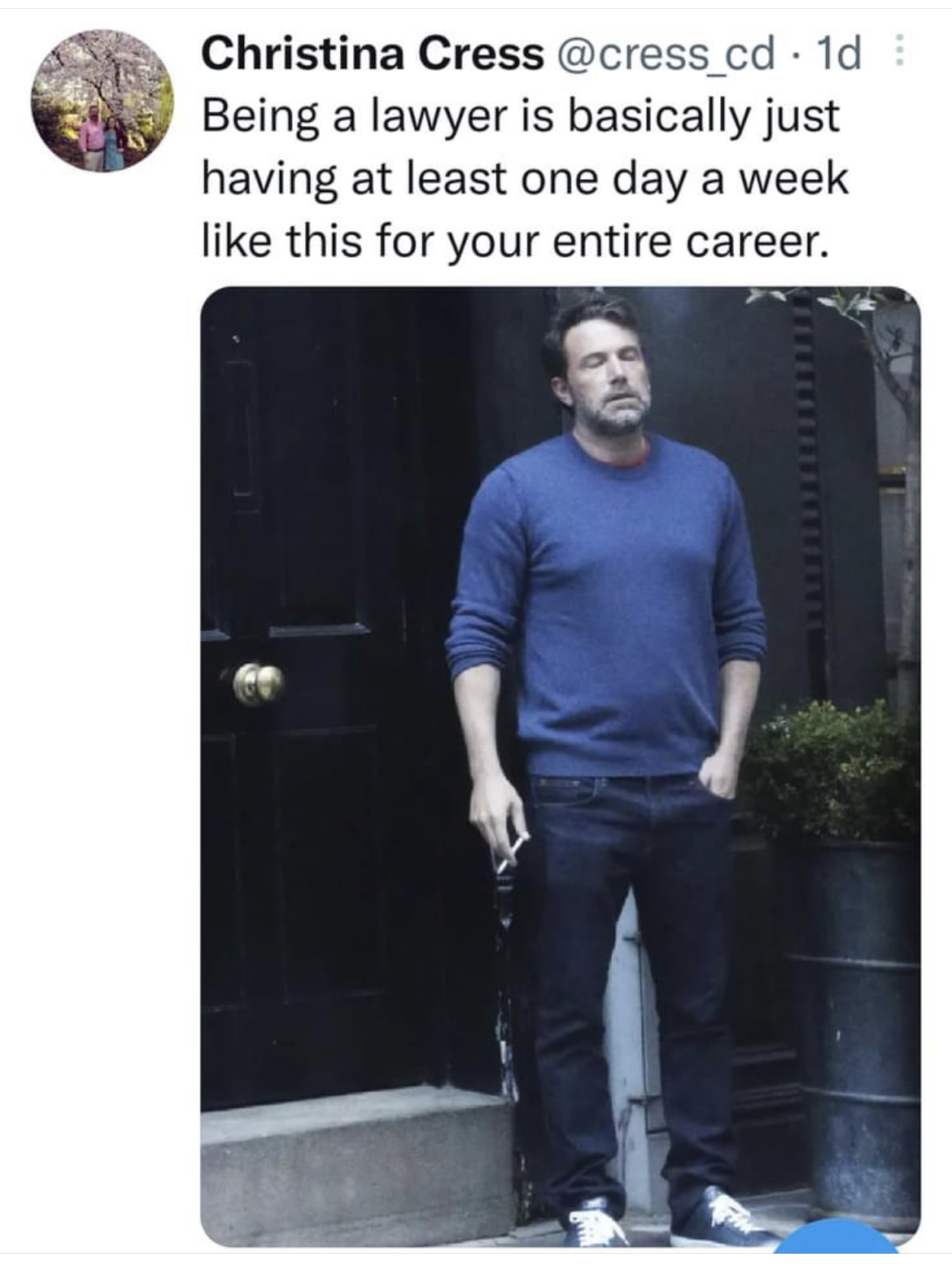

Humorous Takes from #Lawtwitter

“Being a lawyer is just getting a text from a friend or distant relative you have not seen in years that says “hey! It has been a while. Hope you are doing good. Can I ask you a legal question” every day until you die” (2021-04-06, @RilezTweetsEsq)

“Being a lawyer is just answering emails and trying not to cry in front of judges every day until you die” (2021-04-05, @rkshlz)

“Being a lawyer is really just having everyone mad at you, all the time. Opposing party. Opposing counsel. Your client. Your client’s mom. The judge. Clerks. Random people on the street asking for legal advice that is out of your practice area. Your dog. Basically everyone.” (2019-09-05, @CJFoxLaw).

“Being a lawyer is just saying “that’s my understanding but I’ll double check” every 20 minutes…” (2021-08-05, @Brian_AJohnson)

“75 percent of being a lawyer is exercising common sense, 15 percent is conscientious babysitting, 5 percent is the willingness to not say “screw this I’m moving to Guam,” and perhaps the other 5 percent deals with actual mental acuity to practice law..” (2021-08-30, @aurilovesyou2)

“The thing about being a lawyer is you’re never quite sure that you’re actually a lawyer because there’s always some kind of looming dread that you did something wrong many years ago during the bar application and they still haven’t noticed.” (2021-08-24, @rkshlz)

“Calling your client with news of an exceptional outcome is officially the best feeling in the world… Sometimes, justice prevails.” (@sara_m_little)

And from Instagram:

Reflection Questions

- Although in parts humorous and depressing, these tweets contain important kernels of wisdom about competencies in law practice. What ideas about law practice are contained here? What does it tell you about learning competencies for lawyers?

- Review the Law Society of Ontario’s Experiential Learning Competencies. Which of these have you (or do you plan to) meet during your placement?

- What do you think the advantages and disadvantages of articling are in Canada? Ontario specifically?

- What are some of the competencies you are learning in your placement thus far? It’s a good idea to keep track of these over time in a journal.

- In your view, what are some critiques of self-regulation? What are some dangers if the legal profession is not longer able to remain self-regulated?