1.6 The What, How and Whom of Work-Informed Learning

Gemma Smyth

The What, How & Whom of Work-Informed Learning

In this section, we explore “from whom”, “what”, and “how” students learn in a work-informed learning context. This section is lengthier than others, but is important in setting out some essential ways of learning that differ significantly from dominant methods of instruction in legal education.

From Whom do Students Learn in WIL?

Given the context in which most learning in law school takes place, the sources of learning logically follow. Students will typically learn from:

- Professors/ instructors,

- Colleagues (other students in the program),

- Career services staff,

- Mental health professionals,

- Elders,

- Alumni, practicing lawyers, judges, other legal professionals associated with the law school,

- Other staff employed by the law school-coordinated programs.

REFLECTION QUESTIONS

- Who else has been an important source of learning for you in law school?

- Consider – are these people formally employed at the university or college, or are they external to the law school? What impact might employment status on their ability to support your learning, or for you to learn from them?

- List one person who you have learned the most from during law school. What role did they play at the law school (or connected to your law school journey)? What characteristics made them an excellent supervisor, mentor, or colleague?

- Thinking of yourself as a future supervisor or mentor, what values do you wish to embody? What do you hope your mentees will learn from you?

In work-integrated contexts, learning is quite different from a lecture-style class. Clinic, externships and other placements take place primarily in a real life (sometimes called “live client”) context. Even when a student is doing research or working in an appellate context, the work has real impacts. Because students will be learning from lawyers doing real-world work, students typically need to shift their expectations about where learning occurs, and who is acting as a teacher – either formally or informally.

Writing about learning in a clinical environment, Patrick Brayer notes:

“[S]tudents learn from three main systemic sources: learning from people they work with and for, learning from clients (including the client’s social and professional system), and learning by interacting mentally and emotionally with self. Throughout her career, a practitioner will draw from the resources that are her environment. For example, her supervisors and colleagues, as well as judges and opposing counsel, will serve as a continual resource for information, assistance, strategizing and reflection. One shortcoming faced by many practitioners is the inability to effectively interact with individuals who make up their environment…”

Patrick Brayer, “A Law Clinic Systems Theory and the Pedagogy of Interaction: Creating a Legal Learning System” (2012) 12:1 Conn Pub Int LJ 49.

Brayer describes the clinical environment as a “learning system” in which law students are exposed to the complex milieu and relationships that make up a professional context. The section on reflective practice will engage more deeply with these ideas.

Brayer’s insights about the challenges practitioners face in interacting with others – essentially, recognizing and maintaining relationships – are important. Law school can privilege certain skills – for example, cognitive efficiency and precision, doctrinal analysis, and intellectual analysis. All these are important, but without supplementing these with relational skill, the opportunities presented in a workplace environment will be lost.

Regardless whether students are working in a firm, a court or tribunal, a nonprofit, clinic, or other context, you will be introduced to a range of people who play distinct roles. In most placements, two main people will support your work: Your onsite or placement supervisor and your academic supervisor. There are many other people and relationships essential to a successful clinical or externship placement. A description of these roles is also contained in this section.

Learning from Supervisors

The roles and tasks of a supervisor differ depending on context. In a clinic, the lawyer supervising students is called a clinic lawyer, supervising lawyer, clinic lawyer, clinical supervisor, or other term. This person may also be the instructor in a clinic-connected seminar class. This person is extremely important to the learning experience. Their license is also the auspices under which students are permitted to practice. Supervising lawyers in a clinic play many other roles, depending on the clinic. Alongside supervising students, they may carry their own files, engage in grant writing or fundraising, play administrative tasks, supervise other staff, work in community advocacy contexts, and so on. Sometimes, there is only one supervising lawyer at a clinic. In other cases, there is a team of lawyers acting as supervisors in different legal matters.

In an externship and some clinic programs, an onsite supervisor (or placement supervisor) is the person to whom students report for work-related tasks. This person plays a role very similar to an articling “principal” (the person who will supervise articles), but with different supervision requirements. Students are also working under their supervisor’s license. This person will give assignments, feedback, and generally make sure students get a good experience. Students might also get work from other lawyers, community legal workers, or others. Often (but not always), supervisors do not have training in student supervision. This is not universally true (and, likewise, clinic supervisors often get very little training in pedagogy or supervision), but often the workplace is not primarily an educational context. In contrast, most student legal clinics understand themselves to be primarily a place of education and client service. The degree to which a supervisor understand themselves to be an educator, mentor, role model, etc. varies from person to person.

The student’s relationship with the supervising lawyer or onsite supervisor is essential to a good learning experience. The supervisor is the person students will probably interact with most. This person assigns work and gives feedback. They support the student’s learning goals and deal with issues as they arise. This person might also be approached for a reference letter, career advice, work/life balance advice, or other information outside the strict confines of assigned duties.

The supervisor is also helpful in figuring out how students want to (or perhaps don’t want to!) practice. They are models of professional identity, ethical boundaries, relationships with clients, and so on. Part of the student’s role is therefore to be a keen observer of the onsite supervisor and others in the workplace (see the section on “professional noticing”). Onsite supervisors are a great source of information as students negotiate the substantive, ethical, and professional aspects of lawyering.

Professor Neil Gold describes the roles that supervisors play in a law student’s legal education:

“The supervisor, as guide and role model, should seek to be: thoughtful; insightful; measured-to-person, need and context; learned; holistic; and above all, constructively helpful. The importance of the role of the clinic supervisor in explicating and supporting student learning cannot be understated. This interpretive and reflective modeling and methodology can contribute to students’ lifelong habits of learning and problem solving. In engaging the whole student, her thoughts, feelings, hopes and fears, the supervisor simultaneously engages the already stimulated affect and intellect of the student in her quest to deliver signal service. In this model, the student’s experiences as primary actor and her thinking and feeling about them before action, in action and upon reflection are the focal point for guided debriefings and interpretations by the supervisor and often by the student herself once she has been trained to reflect in and on action.” (Neil Gold, “Clinic Is the Basis for a Complete Legal Education: Quality Assurance, Learning Outcomes and the Clinical Method” (2015) 22 Int J of Clinical Leg Education 1.)

Challenges & Benefits for Supervising Lawyers

The role of supervising lawyer – whether at a clinic, externship, or other legal context – has significant challenges. Many clinicians and lawyers involved in Canadian experiential education are not professors. This means they are typically not involved in the curricular or governance processes of the university. They are often also professionally marginalized. A lawyer at one Canadian legal clinic described some of the challenges as follows:

“I would say that when I came [to the clinic] not a lot of time was spent determining whether or not I was going to be a good educator: people were wondering what my legal skills were. The idea flows from the way that the practical aspect of law has been taught, which is: take individuals, have them go to law school, give them some abstract education, and then plunk them down in a work space, and they will learn how to practice law. I tend to think that that’s misguided, particularly given experiential education theories. But if the number of credits that the two supervising lawyers are involved in teaching were to be compared to the number of credits that a professor at the university was involved in teaching, our course load would actually be higher than most of the professors at the university. But, we aren’t professors at the university, and we aren’t really considered externally as being teachers. We’re considered to be lawyers.” (129)

Many lawyers are paid less and have less control over their daily work than professors. These working conditions are part of other challenges. Given the term model at law schools, students are typically at an externship or clinic for four months at a time. Students must be trained and go through a steep learning process to be able to adequately engage in the work. It requires mentorship, engagement, and energy. This process can be exhausting. As one lawyer notes:

“I think the biggest challenge is trying to figure out how to let go of control [of client matters] while also working to ensure that the level of service that is being provided is sufficiently high for you as a professional to be happy, and I think that that’s a really difficult tension to figure out. I also think that there’s a challenge around just the issue of capacity… the difficulty is the demands of time that are placed on me as a lawyer that are associated with education, and the effect that has on my ability to schedule my file work. ‘Cause I’ll go home, and I’ll think to myself: “Oh yeah. This has to get out. I can put three hours in on it tomorrow.” And then being at the office with ten students coming to ask questions about forty files means I will manage to get forty–five minutes done on it, and it’s not a straight forty–five minutes. I do think that there’s a downside to having this changeover every three months.” (136-7)

Supervision can also bring joy and satisfaction for supervising lawyers. Seeing students learn, create community, work with clients, and grow quickly in a few months can be professionally rewarding. Students often graduate from experiential programs committed to clients and with greater skill. Again, one lawyer notes:

“I also think that one of the benefits is the community that can be created… with students, and not just the sort of, the spark that students bring, but the fact that the people who work together…feel really close and support each other well. And I think there’s sort of, yeah, something special about the work environment…, both with and without students that can be pretty special, and then I think there’s a long-term benefit of being able to see the impact that… work has on people who are doing things that I don’t know that they necessarily would have done were they not to be exposed to the different areas of law…” (137)

More information and tips regarding working with your onsite supervisor are contained throughout this coursebook.

Academic Supervisor

Most externship programs and some clinic programs also have an academic supervisor (typically a faculty member or adjunct professor). This person is employed by the law school to set up placements, develop policy, and support students throughout their placement. This person also usually teaches the externship seminar course that accompanies the placement.

This person will have crafted the placement itself and will help guide students through the learning experience; as such, student feedback on the placements is essential to program improvement.

The academic supervisor can also act as a navigator for law school policy and procedure, as well as act as a sounding board for issues that might arise. The academic supervisor has typically worked with many students new to a legal workplace environment and will have good advice and strategy to deal with issues that arise.

While the work-informed learning environment is comprised of a web of people and relationships, these two positions (academic and onsite supervisors) will guide much of the experience.

Reflection Questions

- In thinking about your “learning systems” growing up, who did you learn from in your earliest years, and how was your learning most impactful at that time? Consider as you aged through elementary, middle, and high school – who comprised your learning system? How and why did you begin expanding your system? How did you become more purposeful with how you engaged these people over the years?

- How do you plan to once again expand your learning system to use the program seminar component to explore the questions you have about legal practice?

- What is most concerning to you about a practice environment? How could the seminar support you in figuring out a path to resolve these worries?

- What do you want your supervisor to know about you? What will be important for them to understand about you to bring out your best work?

- How will you establish a good relationship with your supervisor? What do you need to establish before working together? Consider:

- How do they prefer to communicate? Phone, email, text, other?

- Do they prefer to set a weekly or biweekly meeting with you?

- What tasks do they already have planned for you?

- What timelines to they have in mind for this work?

- Are there any practices that they will not appreciate in your work?

- How do they want to give feedback on your written work?

- What other questions will be important to ask your onsite supervisor?

- In an online environment, what additional skills are required to build a relationship with the onsite supervisor?

- What is your conflict resolution plan? While some students have a conflict-free experience, others do not. Preparation is better than pure reaction. As such, what role can the academic supervisor play in resolving potential issues that arise in the placement?

- What particular challenges and benefits do you think supervising lawyers experience from their supervision and mentorship with law students? How might their working conditions be amended to take this work into consideration?

Other Essential Sources of Learning

Students will be exposed to a range of other people besides the onsite supervisor in the course of an externship or clinic experience. As discussed earlier, firms, clinics, and other law offices often employ administrative support people, paralegals, community legal workers, and a host of other people who will have varying roles in the student’s placement. While some will have a more formalised role, they are all sources of learning. These roles are outlined further here.

Law Clerk

The term “clerk” means different things in different contexts. Students might be more familiar with the term “judicial clerk” which is an assistant to a judge who conducts research, drafting, opinion writing, proofreading, and related services to judges at all levels of court.

However, a “law clerk” is an administrative professional who does a wide range of legal work in a firm and other settings. The duties of a law clerk typically include routine legal and related duties under the supervision of a licensed lawyer. Law clerks sometimes also have firm, corporation, or government management duties. Law clerks can join the Institute of Law Clerks of Ontario but it is not a regulated profession and law clerks are not specifically authorized to undertake any legal work except under the supervision of a lawyer.

Administrative Assistant

Legal administrative assistants perform a variety of secretarial and administrative duties in law offices, legal departments of large firms, real estate companies, land title offices, municipal, provincial and federal courts and government. Many law firms employ one or more administrative assistants to perform a range of duties including taking calls and scheduling appointments, maintaining filing systems, and so on. Administrative assistants are extremely important to the efficient operation of a firm, government office, clinic, or other workplaces. As above, it is important to understand the role of an administrative assistant and how you are required to interact with that person. What duties do they perform? Where is the boundary between their work and yours? Under whose supervision to they work?

Paralegal

Paralegals prepare legal documents, advocate, and conduct research to assist lawyers or other professionals. Paralegals can also practice on their own. Independent paralegals provide legal services to the public as allowed by government legislation, or provide paralegal services on contract to law firms or other establishments.

In Ontario, paralegals are regulated by the Law Society and are able to provide legal services in defined areas such as small claims court, traffic court, tribunal work, and some criminal matters. Paralegals are subject to the Paralegal Rules of Conduct which governs their conduct in a similar fashion to the Rules of Professional Conduct for Lawyers. The role of paralegals in firms has spawned almost endless memes speaking to their essential role in firms, mostly with the moniker “Chill Paralegal”.

Community Legal Worker

Community legal workers are often employed by legal clinics to engage in advocacy, community development, law reform, public and community legal education, and other client services that are often adjacent to but not strictly “legal” work requiring licensure. CLWs might organise campaigns, advocate for law reform, work with community groups, and so on. CLWs’ knowledge of the law and legal systems is extremely important for lawyers, and CLWs and lawyers often work together on campaigns or projects. CLWs are not permitted to give legal advice.

Social Worker

Social workers help individuals, couples, families, groups, communities, and organizations develop the skills and resources they need to enhance social functioning. They might provide counselling, therapy, and referral to other supportive social services. Social workers also respond to other social needs and issues such as unemployment, discrimination, and poverty. They are employed by hospitals, school boards, social service agencies, child welfare organizations, correctional facilities, community agencies, employee assistance programs and band councils, or they may work in private practice.

Social workers can work in a community clinic or firm, or they can work as referral sources for lawyers. Within a clinic or firm context, social workers play a variety of roles, including supporting clients with non-legal issues, community advocacy and community development, and so on. There are many ethical issues that arise when working in an interdisciplinary environment, including different confidentiality and reporting obligations. Social workers keep notes and maintain files differently from lawyers. If students work closely with social workers, it is important to understand ethical and practical issues in advance.

It is very helpful to understand the roles social workers play in an organization. When do social workers want to be brought into a case? When might they collaborate with lawyers? How do lawyers and social workers collaborate on individual or systemic projects?

Community Service Worker

Social and community service workers administer and implement a variety of social assistance programs and community services. They are employed by social service and government agencies, mental health agencies, group homes, shelters, substance use centres, school boards, correctional facilities, and other establishments.

Community service workers are often confused with social workers. When clients talk about “workers” it is important to clarify what kind of worker they are referring to, as they have very different roles vis-à-vis clients.

Judge

Judges adjudicate civil and criminal cases in courts of law. Judges preside over federal, territorial and provincial courts. While we typically associate judges with decision making, they can also play roles in settlement conferences, pre-trial conferences, and so on.

In Ontario, Judges of the Superior Court of Justice preside over a variety of matters including criminal prosecutions of indictable offences, summary conviction appeals from the Ontario Court of Justice, bail reviews, civil lawsuits, and family law disputes. Judges of the Ontario Court of Justice deal with a wide range of family law cases (including child protection, custody, access, support and adoption) as well as approximately 95% of the criminal charges laid within the province. Judges of the Ontario Court of Justice are appointed by the Judicial Appointments Advisory Committee. The requirements are the same as the Superior Court of Justice.

Justices of the Peace of the Court have jurisdiction with respect to provincial offences, bail hearings, and search warrants. Their responsibilities also include, but are not limited to, presiding in criminal set-date court, and hearing section 810 Criminal Code applications. Appointment of Justices of the Peace is governed by the Justices of the Peace Act. It is not a requirement to be a lawyer or even have a legal education but Justices of the Peace must have at least ten years of work experience.

More about Judicial Internships or Clerkships is contained in a later Chapter.

Hearing Officer (Tribunal Member, etc.)

Administrative tribunals are designed to reduce the cost, time, and formality that is present in settling disputes through the court. Specific tribunals are creatures of legislation. For example, the Social Benefits Tribunal is established under part IV of the Ontario Works Act and the Human Rights Tribunal of Ontario is continued under the Human Rights Code.

In contrast to judges who have generalized knowledge of various areas of the law, tribunal members usually have specialized knowledge about the topics they are asked to consider. Members may sit alone or, less frequently, in panels for more complex issues. Members are responsible for conducting fair hearings and making final decisions about issues.

Reflection Questions

- Which professional roles have you observed in your placement thus far? What are the reporting relationships and duties of each person? What is your relationship to each person?

- How do people in a legal working environment work with one another? How do they operate to best serve clients and communities? Have you noticed any hierarchies? How do they manifest? Where does the student fit in this hierarchy?

- What type of power relationships exist in your interactions with the above roles? Which role will have (or has had) the most impact on your success as a student?

- How would you react if some people in the workplace are less thrilled about having a student at the office than others? How might you respond if a client challenges you because you are “just a student?”

Clients

Some of the most important sources of knowledge in a client-facing placements are clients. Work-informed placements have varying degrees of interaction with clients – some are almost entirely client-facing while others are research, appellate, or policy based with little direct client interaction. Regardless, clients’ voices are essential in most lawyers’ work, even if that voice is expressed as the public interest, from community groups, or elsewhere. Typically, we think of a client as an individual with whom the lawyer forms a solicitor-client relationship. However, lawyers work in many different ways with clients. Sometimes, a lawyer will work with a client to provide “brief service” (basically, basic or summary legal advice in a single or very limited number of appointments with no ongoing relationship). Sometimes, the client is a community or group. Sometimes legal work is done on behalf of a social movement. In another context, work might be comprised of research and writing for a judge or other decision-maker in the absence of a single “client”.

There are important ethical questions that arise in suggesting that students should “learn from” or “learn with” clients. The idea that law students “use” clients for their own learning has important and potentially troubling implications.

However, there is also some evidence showing that students working under supervision provide high quality service with similar outcomes to those of a licensed lawyer. See, for example Shanahan and co-authors note that “[w]e find that clinical law students behave very similarly to practicing attorneys in their use of legal procedures. Their clients also experience very similar case outcomes to clients or practicing attorneys… our findings are consistent with claims that law school clinics help prepare students to be practicing lawyers and to service low-income clients as well as lawyers do.” Colleen F Shanahan et al, “Measuring Law School Clinics” (2018) 92(3) Tulane L Rev 547.

Reflection Questions

- The author notes that “[t]he idea that law students ‘use’ clients for their own learning has important and potentially troubling implications.” What might these be? What steps can be taken to mitigate the chances of this occurring?

- If students engage in work that is not directly client-facing, how can they ensure client voice is still engaged in their work? What is the lawyer’s ethical duty in this regard?

What do Students Learn?

Learning in clinical and externship programs requires a set of skills that will serve students throughout their professional careers. For example, students must employ self-directed approaches to learning, exhibit leadership in organizing their tasks to meet learning goals, and constantly reflect on their learning.

As we know, humans adapt to new experiences by building from past experience. Students can also consider these new experiences against the backdrop of both their past experiences and their future goals.

Reflection Questions

- Think back to when you first applied to law school. What interested you in applying? Has that changed after 1L? How does a work-integrated learning placement fit into your overall goals for law school?

- This text digs into goal setting in a later chapter. For now, consider: Are there connections between your placement experience and your career goals? Personal growth goals?

Because work-informed placements come in so many different forms, there is a wide range of possible learning that comes from a placement. Some learning is about substantive areas of law ‘on the ground’. In a criminal law placement, the student might learn more about which arguments are particularly compelling in a bail hearing in front of a particular judge. Other learning outcomes are more “task-oriented” – learning how to write an opening letter or demand letter, for example. Others are about personal and professional development – such as learning how to set appropriate boundaries with clients, supervisors, and yourself. Others are about the nature of law – such as learning where gaps in the law lead to inequity for clients. Other learning is more intangible, perhaps about the culture of a particular firm. Many students talk about personal learning, perhaps about how to better manage their time, take care of their wellness, and about crafting their identity in the workplace.

Research on Competencies & Characteristics

Law students are likely familiar with constitutes success in a classroom context, and the competencies gained in this context. A placement shifts the focus to a different set of learning (although with overlapping competencies typically related to legal analysis and reasoning). There is growing empirical evidence related to what clients and lawyers value in practice. Some of this research might help students think more broadly or creatively about their learning goals. One set of competencies that are often neglected are those most important to clients. The Canadian Bar Association’s “Futures Report” examined some of these competencies.

Canadian Bar Association (CBA) “Futures Report”

“The Legal Futures Initiative canvassed participants about changing client expectations and the practice of law, and what clients value most from their counsel. Technology, cost pressures, and business management tools are already transforming relationships between lawyers and their clients. Even the concept of value in legal services has shifted; thinking like a client means that lawyers are moving beyond traditional conflict resolution to providing increasingly strategic and tailored problem-solving or avoidance.”

Part of the research included interviews with clients. Some of the findings are described below.

Clients and value

The following characteristics were identified most often as those that clients value:

- Honesty, even when that honesty requires that the client be disappointed;

- Integrity, also described as objectivity or an independent mind;

- Effective communication in dispensing advice and listening, and demonstrating a willingness to engage the client as an active participant in the management of their own matter;

- Empathy, or as described by senior in-house counsel from the NGO sector, “good bedside manner.”

Inherent within these traits is the lawyer’s ability to connect with clients. A mid-career private practitioner noted that a good lawyer possesses “the ability to understand what the client sees as important, rather than what the lawyer sees as important.” Our increasingly sophisticated and cross-border world demands new skills from lawyers. Emerging indicators of value identified by respondents ranged from business acumen to public relations, risk management, expertise in creating legal teams, facility to work in multi-disciplinary teams, and strategic, visionary thinking.”

Canadian Bar Association, “CBA Legal Futures Initiative: Report on the Consultation” (February 21, 2014) at 7.

Another source of empirical evidence regarding what lawyers think are important competencies is contained in the IAALS “Foundations for Practice” report. Consider the overlap and departures from the CBA Report.

Foundations for Practice

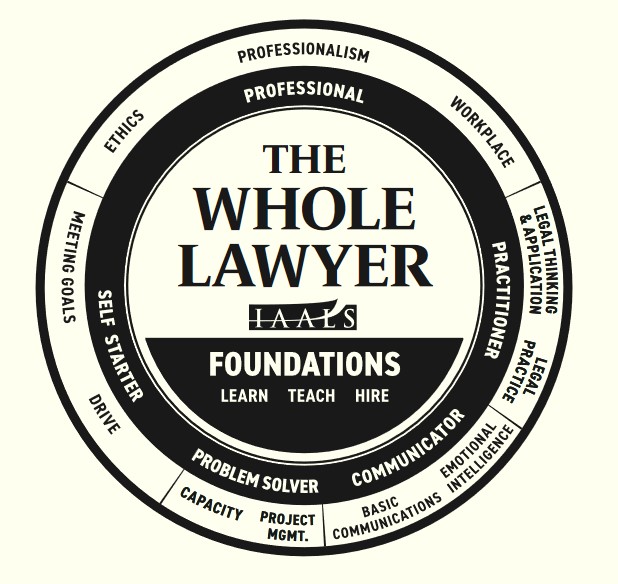

The Institute for the Advancement of the American Legal System (IAALS) has conducted significant empirical research into what competencies might comprise “the whole lawyer”. The IAALS research team interviewed over 24,000 lawyers at various stages in their careers about the legal skills, professional competencies, and characteristics that make lawyers successful. Previously, more traditional notions of practice excellence focused on substantive legal knowledge. The IAALS Foundations for Practice report found something quite different:

“76% of characteristics (things like integrity, work ethic, common sense, and resilience) were identified by a majority of respondents as necessary right out of law school. When we talk about what makes people—not just lawyers— successful we have come to accept that they require some threshold intelligence quotient (IQ) and, in more recent years, that they also require a favorable emotional intelligence (EQ)… [S]uccessful entry-level lawyers are not merely legal technicians, nor are they merely cognitive powerhouses. The current dichotomous debate that places “law school as trade school” up against “law school as intellectual endeavor” is missing the sweet spot and the vision of what legal education could be and what type of lawyers it should be producing. New lawyers need some legal skills and require intelligence, but they are successful when they come to the job with a much broader blend of legal skills, professional competencies, and characteristics that comprise the whole lawyer.”

This image from the “Foundations for Practice” report, demonstrate the array of skills that their research has shown are important for excellence in lawyering.

The IAALS Report is a useful tool to expand consciousness around what law students might learn in a placement, especially as it pertains to their entry-level practice.

Reflection Questions

It is also important to keep in mind that the placement site learns from the student. Many supervisors talk about the impact students have had on their organization and themselves personally and professionally.

- What might your placement site learn from you?

- In your previous work experiences supervising or working with someone else, what did you learn from them?

- Throughout your placement, you might want to keep an ongoing list of the competencies you are learning. You might wish to consider how you improve at that skill throughout the term,

How do Students Learn in WIL?

In most common law classes, students formally learn through a traditional set of methods including:

- Reading (mostly cases, some case commentary, legislation, and perhaps journal articles, CANs (condensed annotated notes),

- Listening (typically to lectures by instructors or visiting guests, perhaps to colleagues in small or large group contexts, videos),

- Discussing (in class: large group question/answer regarding class content, small group discussions, outside of class: informal and formal discussion in study groups),

- Simulated experiences (typically, role plays).

In this section, we set out some key concepts and contexts that depart from these ways of learning. This is not to say that reading and listening are not important ways to learn; they are simply more dominant in a classroom setting.

The following explores:

- Learning from the Land

- Learning in (and from) Uncertainty

- Self-directed Learning, and

- Two Reflective Practices: Learning through Observation, and Professional Noticing

REFLECTION QUESTIONS

- Consider the sources of learning you have encountered in your legal education thus far: who have you learned from? What have you learned from? How have you learned?

- What other pedagogical approaches have you seen experienced thus far in your legal education? Which methods have been most effective for you?

- How is the move toward more online education impacting learning, particularly learning through observation?

Learning from the Land: Land-Based Learning

In classes and experiences focused on Indigenous legal systems, learning might come from many other sources including Elders, community, and ceremony. Indeed, each student’s cultural and community context will impact how and from where they glean knowledge and understanding.

Many law schools are incorporating land-based approaches to learning, although how deeply and widely land-based learning occurs varies significantly. Wildcat, Simpson, Irlbacher-Fox and Coulthard write,

“Settler-colonialism has functioned, in part, by deploying institutions of western education to undermine Indigenous intellectual development through cultural assimilation and the violent separation of Indigenous peoples from our sources of knowledge and strength –the land. If settler colonialism is fundamentally premised on dispossessing Indigenous peoples from their land, one, if not the primary, impact on Indigenous education has been to impede the transmission of knowledge about the forms of governance, ethics and philosophies that arise from relationships on the land. As Leanne Simpson argues in the feature article of this issue, if we are serious about decolonizing education and educating people within frameworks of Indigenous intelligence, we must find ways of reinserting people into relationships with and on the land as a mode of education…Land-based education, in resurging and sustaining Indigenous life and knowledge, acts in direct contestation to settler colonialism and its drive to eliminate Indigenous life and Indigenous claims to land.” (Wildcat, Matthew et al, “Learning from the land: Indigenous land based pedagogy and decolonization” (2014) 3:3 Decolonization: Indigeneity, Education & Society I-XV at II-III.)

Reflection Questions

- How do land-based pedagogies disrupt both classroom-based pedagogies as well as clinical and experiential pedagogies? How might they deepen learning in all these contexts?

- How does land-based learning intersect with clinical and externship approaches? How might land-based learning disrupt the dichotomies and assumptions inherent in clinical and experiential learning?

Learning in (and from) Uncertainty

Another common element in work-informed learning contexts is uncertainty. This could include uncertainty about what you will do in a given day, how a client will react, what support you might have, whether a supervising lawyer is available, whether a hearing is adjourned, how a judge will decide on an adjournment, whether or not a given action is ethical, and so on. In fact, much of lawyering takes place in situations of uncertainty.

Dave Cormier researches and writes about uncertainty in education. In this video, and this book, he argues that:

- Workplaces are full of uncertainty.

- Uncertain problems are often complex problems that involve people judgement and weighing multiple issues against each other.

- Uncertain problems often don’t have answers.

- You can get better at learning for uncertainty, but you have to take responsibility for it.

- The community of the people in your field are your curriculum.

This degree of uncertainty can be very difficult for some students. As Professor Cormier argues, most modern curriculum is constructed for certainty. There are rubrics, grades, problems in fixed contexts (eg, hypotheticals), classroom discussion that gears toward right and wrong, and so on.

Reflection Questions

- Professor Cormier writes that “the community is the curriculum”. What does that mean in a work-informed learning context? Who is “the community” in your context? How does turning the context away from text- and lecture-based learning mean for how you will learn.

- Professor Cormier writes about “taking responsibility” for your learning. What does this mean for you? Why might taking responsibility for your learning be important in work-informed learning? How might you take greater responsibility for your learning?

Self-Directed Learning

Self-directed learning is a concept closely related to taking responsibility for a student’s own learning. One of the key themes of work-informed learning placements is self-directed learning. This is a concept with many meanings and applications. Importantly, it does not mean unsupported learning.

In many work-informed learning contexts, students are asked to set learning goals for themselves. This might occur formally with a pre-formulated “learning agreement” or another document. It might be informal through discussions with a supervising lawyer. It might be implied in assignments such as reflective writing or journaling. Sometimes, students set their own goals and engineer their work to meet as many of their goals as possible.

As the name suggests, self-directed learning focuses on the student’s ability to direct their own learning. Popular beginning in the mid-1970s, this idea posits that learners (especially adult learners) benefit from setting their own goals and planning what they would like to learn.

Critical pedagogical theorist Jack Mezirow argued that the concept of self-directed learning should focus on the capacity of learners for critical self-reflection and, ultimately, changing their lives. (Jack Mezirow, “A Critical Theory of Self-Directed Learning” (1985) 25 New Directions for Continuing Education 17). Clinical and experiential learning relies heavily on this notion, largely because students are placed in situations that impact real people or simulate live client environments. Students are expected to take on a professional role, use professional judgment, and learn from experience.

Lawyers are also required to be lifelong and self-directed learners. In Ontario, for example, lawyers are required to complete Continuing Professional Development annually. Specifically:

Lawyers and paralegals who are practising law or providing legal services must complete in each calendar year at least 12 CPD Hours in Eligible Educational Activities consisting of a minimum of 3 Professionalism Hours on topics related to professional responsibility, ethics and/or practice management and up to 9 Substantive Hours per year. Effective January 1, 2018, lawyers and paralegals must complete the CPD Equality, Diversity and Inclusion (EDI) Requirement. Lawyers and paralegals must complete a total of 3 Professionalism Hours that focus on advancing equality, diversity and inclusion in the lawyer and paralegal professions between January 1, 2018, and December 31, 2020. Each year thereafter, lawyers and paralegals must complete 1 Professionalism Hour that addresses issues of equality, diversity and inclusion. These hours count towards the 3 CPD Professionalism Hours required each year.

Part of self-directed learning is setting learning goals. The practice of goal setting is common in other professions such as medicine, business and social work, but the idea is still relatively uncommon in law. Perhaps because it is somewhat counter-cultural in law, drafting learning goals can be very difficult. Many students have not had the chance to direct their own learning. Students might also not be quite sure what to expect in any particular placement. This coursebook gives some ideas about what students might want to learn, but the most important is re-visioning yourself as being in the driver’s seat of your own learning. The context in which learning takes place is, of course, never individual (especially in clinical and experiential learning environments). However, the student plays a much more directive role in these contexts than, for example, in a class with mandatory readings and a 100% final exam.

Reflection Questions

- What does it mean to you to be “in the driver’s seat of your own learning”? Are people ever really solely directing their learning? What role does community play in supporting learning?

- What previous experiences have you had directing your own learning? This could have been in a job, a complicated personal or professional relationship, parenting, a course you took “just for fun”, a volunteer experience, or other context.

- In this context, what did you do to facilitate your own learning? How did you feel when in this less-structured learning environment?

- What, if anything, makes you nervous about drafting a learning agreement? What are you looking forward to in the process?

Reflective Practice

Reflective practice is an essential part of learning. This section briefly introduces two important skills related to reflective practice: observation and professional noticing. More about reflective practice is contained in a later chapter.

Learning through Observation

One essential component of profession learning is the ability to learn through and from observation (or “noticing”). All animals, including humans, learn through observation. Some cultures are more adept at teaching through observation; indeed, it can be a regular, structured part of learning a craft, a survival skill, or other task done by adults in a community. In writing about the learned practice of weaving in a Mayan context, Gaskins and Paradise write:

“1) the learning process takes place in the culturally structured context of ongoing work, and the model’s primary motivation during the activity was [the activity] itself, that is, to get something done other than teaching or demonstrating; 2) the learning was not expected to contribute to the work in any significant way while learning; and 3) the learner was given primary responsibility for organizing the learning task…”

Suzanne Gaskins and Ruth Paradise, “Chapter 5: Learning Through Observation in Daily Life” in Lancy, David et al, The Anthropology of Learning in Childhood (Maryland: Rowman & Littlefield, 2010, at 85-86).

In work-informed context, learning through observation is often an important first step in understanding how to do a lawyering task. This is particularly true in client interviewing and client counselling, negotiation and mediation, litigation, and other forms of oral advocacy. There are other parts of written legal work in which the student observes precedents or other examples of expected work as a first step in producing their own work. Students might also “shadow” a lawyer or judge to understand a fuller picture of the “life of a lawyer”. Job shadowing introduces many other aspects of lawyering including interactions between colleagues in an office, file management and billing practices, and so on.

Reflection Exercise

- Think of an activity or practice you learned as a young person that you learned through observation, especially skills that require you to “do” something (planting a garden, caring for an animal, etc). Consider how you grew in your competence in that activity. Consider what skills you used to learn through observation.

- What skills learned as a younger person have you relied upon in your current learning context?

Professional Noticing

Rooney and Boud write: “a necessary skill that underpins all professional practice is noticing that which is salient”. Their theory of professional noticing helps frame the practice of learning through observation, as well as laying an essential piece of groundwork for lifelong professional learning. They set out three aspects of noticing: noticing in context, noticing of significance and noticing learning. These aspects are described in the excerpt below:

“The first form of noticing is noticing in context. It is about noticing the scope of practices that constitute a professional domain, and how these are bound together and when/how they manifest in the messiness of everyday professional contexts. This is more than discerning the knowledge features of an isolated practice purged from the professional context in which it occurs, but how multiple practices simultaneously happen in authentic situations. Over time, professionals develop a ‘professional frame’ that enables them to fluently read unfolding and complex episodes of practice and how to act in them… This leads us to a second form of noticing, noticing of significance. In the messiness of everyday activity professionals also meet situations where routine interventions are not viable or appropriate. Professionals also need to be able to readily identify what they should be attending to and what they should do if there is any deviation from what is expected. Rose calls this ‘disciplined perception’ (2014 p.73): to notice aspects of practice in order that it becomes available for them to act on. This noticing builds on but moves beyond, simple noticing in context. It is noticing of significance and judging in action what to do about the unexpected. Goodwin (1994) alludes to this when discussing how of the police officers coded Rodney King’s behaviour as aggressive which justified their subsequent actions. Experienced professionals notice significant deviations from the anticipated flow of events and will initiate responses confidently and without delay. This is also what Mason identifies as marking: ‘a heightened form of noticing’ (Mason 2002, p. 33)…Finally… we need to recognise a necessary third form of noticing: noticing learning itself. In educational contexts, there is much noticing required of students. Learners need to notice what is needed of them, they need to utilise important information and direct their own learning activities in the direction required by a clear understanding of the circumstances they find themselves in, and where they wish to end up. Self-direction and self-regulation are initiated by noticing or are preceded by it… It involves a cycle of noticing, intervening, reflection on the outcome, leading to further noticing, intervention and reflection.”

(“Toward a Pedagogy for Professional Noticing: Learning Through Observation” (2019) 12 Vocations and Learning 441.)

Noticing is closely related to reflective practice, discussed in a later Chapter.

Reflection Questions

- In your view, what are some practices that support ‘noticing’? What practices might limit your ability to notice in a professional context?

- In “My Grandmother’s Hands: Racialized Trauma and the Pathway to Mending Our Hearts and Bodies” (2017), author Resmaa Menaken writes about the specific traumatizing impacts of racism from a somatic psychology perspective. The book is full of useful and practical tools, including a set of meditation and reflection exercises. One, reproduced below, focuses on being “present” by “Coming into the Room”, one of the key elements of noticing:

For a few breaths, simply be aware of being in your body. Relax and let the chair support you.

Instagram, @Litigation_God, 2023.

Instagram, @Litigation_God, 2023.