7.1 What does Empirical Research Tell us about Wellness Problems in Law?

Gemma Smyth and Andrew Pace

Introduction

It is well established that mental health disabilities and addictions in the legal profession are experienced at rates higher than the general population, and higher than other than other professions. A Canadian Bar Association report found that “58% of lawyers, judges and law students surveyed had experienced significant stress and burnout, 48% had experienced anxiety and 26% had suffered from depression”. In a 2014-2019 study of lawyers who are members of the Barreau du Quebec, 43% of respondents reported psychological distress, with half of younger lawyers reporting distress (Nathalie Cadieux et al, “Research Report: A Study of the Determinants of Mental Health in the Workplace Among Quebec Lawyers, Phase II – 2017-2019”, Research Report, Université de Sherbrooke, Business School, 2020). Professor Cadieux then led a nation-wide study on wellness in the legal profession, resulting in a report released in October, 2022.

Supported by the Federation of Law Societies of Canada, the Canadian Bar Association, and Université de Sherbrooke the report investigates the wellness and determinants of health for legal professionals in Canada (including lawyers, paralegals and Quebec notaries). Law students were not included in this study. The findings paint an alarming picture of the wellness of Canadian legal professionals. Legal professionals in all areas of practice and in all jurisdictions suffer from significantly high levels of psychological distress, depression, anxiety, burnout and suicidal ideation, with those in the early years of practice experiencing some of the highest rates of distress. The report began by examining the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic but it is clear the pandemic exacerbated pre-existing issues within the legal field that will not disappear. The date below paints a particularly grim picture for lawyers who are women, non-binary, LGBTQ2S+, and disabled all of whom reported the highest levels of stress, burnout, and suicidal ideation. The report should be read in its entirely for nuance. Some preliminary data from the report are set out below:

Groups with the highest proportions of psychological distress

- Women legal professionals (63.7%)

- Legal professionals working in the public sector or NFPO (58.0%) and private practice (58.4%)

- Legal professionals between the ages of 26 and 35 (71.1%)

- Legal professionals with less than 10 years of experience (70.8%)

- Articling students (72.0%; unweighted), Ontario paralegals (65.9%) and Quebec notaries (65.9%)

- Legal professionals living with a disability (74.3%)

- Legal professionals identifying as members of the LGBTQ2S+ community (69.3%)

- Legal professionals working in Nunavut (76.4%)

Groups with the highest proportions of burnout

- Legal professionals between the ages of 31 and 35 (67.0%)

- Women legal professionals under 40 years of age (67.4%)

- Legal professionals working in Nunavut (81.2%)

- Legal professionals living with a disability (69.8%)

- Legal professionals who identify as members of the LGBTQ2S+ community (62.7%)

Groups with the highest proportions of suicidal ideation:

- Legal professionals working in the Canadian territories (29.7%)

- Lawyers (24.4%)

- Legal professionals working in the public sector or NFPO (27.2%)

- Legal professionals who identify as non-binary (61.9%)

Higher than average and problematic substance use in the legal profession is also well documented. These obviously have impacts on lawyers and their loved ones. For legal workplaces and clients, the impacts of poorly managed mental health and addictions results in ethical and professional errors, potentially poor client service, and higher costs. Importantly, these findings have also been echoed in an international context by the International Bar Association.

Literature regarding wellness, mental health and addictions in law is now many decades old. Although data is being gathered and reported, significant research gaps remain (especially in comparison with research in medical education). There is relatively scarce literature specifically focused on Canadian law students, lawyers, and judges (with Cadieux’s study a notable recent contribution). Available empirical data does not often include information regarding social markers, although those links are beginning to be more clearly made. There is also significant research that one could assume relates to mental health, but that link is not explicitly made in the research (for example, we know that women lawyers are more likely to be under- or unemployed and paid less, but there usually no explicit link made to mental health). The degree to which these studies include systemic analyses varies widely (eg, market conditions/ legal marketplace, context of legal practice, context of higher education, systemic discrimination, etc.). There is sometimes disagreement and mixed results in various studies, and the methodology varies considerably; therefore, some generalizations and contradictions are inevitable. Nonetheless, there are several themes that appear repeatedly in the literature. The themes are divided, below, roughly along the continuum from law school through to retirement, with subheadings setting out key themes and possible root causes.

Wellness & legal education

One of the sources of mental health and addictions problems is legal education itself. There is an increasing volume of research on the impact of law school on student wellbeing (although, again, limited information in Canada). Many studies point to the competitive environment in law school epitomized by grading practices and heavy workload. For example, students in law school are positioned as competitors with one another through grading that occurs on a “curve”. High-stakes summative assessments such as 100% final exams can also add stress, as can lack of feedback (Andrew Benjamin et al, “The Role of Legal Education in Producing Psychological distress among Law Students and Lawyers” (1986) 11(2) American Bar Foundation Research Journal 225). Other studies point to the depersonalizing nature of legal education as having negative impacts on students. For example, the case method of teaching tends to turn human problems into an exercise of depersonalized legal reasoning. Clients are rarely discussed outside of clinical contexts. Relationships between professors and students are typically weak or non-existent. There is also very little interpersonal skill development in the law curriculum, which tends to over-emphasize cognitive-based legal reasoning without the relational and affective parts of law practice (Lawrence S. Krieger, “Institutional Denial About the Dark Side of Law School, and Fresh Empirical Guidance for Constructively Breaking the Silence” (2002) 52 Journal of Legal Education 112). Elsewhere, Krieger writes:

“Data from several thousand lawyers in four states provide insights about diverse factors from law school and one’s legal career and personal life. Striking patterns appear repeatedly in the data and raise serious questions about the common priorities on law school campuses and among lawyers. External factors, which are often given the most attention and concern among law students and lawyers (factors oriented towards money and status-such as earnings partnership in a law firm, law school debt, class rank, law review membership, and U.S. News & World Report’s law school rankings), showed nil to small associations with lawyer well-being. Conversely, the kinds of internal and psychological factors shown in previous research to erode in law school appear in these data to be the most important contributors to lawyers’ happiness and satisfaction” (Lawrence S Krieger & Kennon M Sheldon, “What Makes Lawyers Happy: A Data-Driven Prescription to Redefine Professional Success” (2015) 83:2 Geo Wash L Rev 554 at 554).

Some authors point to the very narrow notion of “success” achieved by comparatively few students each year. Others point to the nature of the case method, which might particularly impact “feeling” students. In addition, despite significant strides to talk openly about mental health in law school, significant stigma remains. (See also Lawrence Richard, “Psychological Type and Job Satisfaction Among Practicing Lawyers in the United States” (1994) (unpublished PhD thesis), Sandra Janoff, “The Influence of Legal Education on Moral Reasoning” (1991) 76 Minnesota Law Review 193, K. M. Sheldon & L. S. Krieger, Does Legal Education Have Undermining Effects on Law Students? Evaluating Changes in Motivation, Values, and Well-Being, 22 Behavioural Sciences and the Law 261 (2004), Jerome M. Organ, David B. Jaffe & Katherine M. Bender, Suffering in Silence: The Survey of Law Student Well-Being and the Reluctance of Law Students to Seek Help for Substance Use and Mental Health Concerns, 66 Journal of Legal Education 116 (2016)).

There is also evidence that lack of cultural safety also plays out in the law school classroom. Discrimination experienced by racialized, female, disabled, trans, and other students creates a hostile learning environment impacting student wellbeing. (See Erin C. Dallinger-Lain, “Racialized Interactions in the Law School Classroom: Pedagogical Approaches to Creating a Safe Learning Environment” (2018) 67 Journal of Legal Education 780.; Erin Lain, “Experiences of Academically Dismissed Black and Latino Law Students: Stereotype Threat, Fight or Flight Comping Mechanisms, Isolation and Feelings of Systemic Betrayal” (2016) 45 Journal of Law and Education 279.; Judith D. Fischer, “Portia Unbound: The Effects of a Supportive Law School Environment on Women and Minority Students” (1996) 7 UCLA Women’s Law Journal 81.; Morrison Torrey, “You Call that Education?” (2004) 19 Wisconsin Women’s Law Journal 93.)

There have also been various studies on substance use both in law school and in the profession demonstrating a very serious problem in both contexts (see, for example, American Association of Law Schools, “Report of the AALS Special Committee on Problems of Substance Abuse in the Law Schools” (1994) 44 Journal of Legal Education 35.; Jerome Organ et al, “Suffering in silence: The Survey of Law Student Well-Being and the reluctance of Law students to seek help for substance use and mental health concerns” (2016) 66(1) Journal of Legal Education 116; Canadian Bar Association, Survey of Lawyers on Wellness Issues (Ipsos Reid, 2012) (note this study included law student respondents).

While there is very little research in this area, a few studies demonstrate concerns regarding maladaptive eating in professional programs, including lawyers and law students. (See, for example, Natalie Shea, Shane Rogers and Jerome Doraisamy, “Looking beyond the mirror: Psychological distress, disordered eating, weight and shape concerns, and maladaptive eating habits in lawyers and law students” (2018) 61 International Journal of Law and Psychiatry 90.

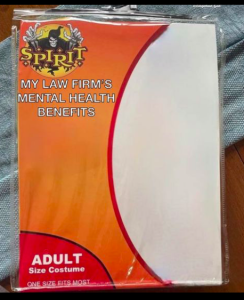

Although not an empirically rigorous indication, the internet is also full of memes about law school – most of which are disturbingly depressing.

Pinterest, uploaded by Jennifer Fisher, 2022.

Wellness & Law Practice

There is a wealth of data on mental health, wellness and addictions in law practice. Work context, stage of career and social markers all significantly impact how lawyers experience practice, and some nuance is lost in much of this literature. Generally, however, some key themes are clear. “Overwork” and the nature of legal work appear repeatedly as problems. Most lawyers do work hours that create work-life conflicts. This is most problematic for certain groups, including younger lawyers. Several studies also point to the illusion of “higher status” positions – meaning, the goal of working in a big firm making more money does not correlate with happiness or satisfaction. (See Jonathan Koltai, Scott Shieman, Ronit Dinovitzer, “The Status-Health Paradox: Organizational Context, Stress Exposure, and Well-being in the Legal Profession” ; Canadian Bar Association, “Survey of Lawyers on Wellness Issues”, Legal Profession Assistance Conference, 2012; International Bar Association, “Mental Wellbeing in the Legal Profession: A Global Study” (London, England: 2021). Cadieux’s study also pointed to a lack of affordable, accessible mental health supports for lawyers, either through their workplaces or through their Law Societies.

Instagram, @Litigation_God, 2022

Other studies point to some specific psychological and sociocultural elements of practice that impact wellbeing. First, the profession often requires lawyers to disconnect from their feelings (see above regarding legal education). Some authors write about the pessimism and negativity that pervades law practice. Others write about feelings of “anticipatory anxiety” – dread or fear in anticipation of a future event (which the body interprets as a threat). Perfectionism also pervades law practice, and while lawyers might view this as a good thing, it can also be debilitating. (See New York State Bar Association, “Report and recommendations of the NYSBA Task Force on Attorney Well-being” (2021)).

There is also limited, although important, research on the specific wellness issues that arise from social justice practice. One activist noted there is a “culture of martyrdom” in social justice and human rights activism that results in burnout (subject in Cher Weixia Chen and Paul Gorski, “Burnout in Social Justice and Human Rights Activists: Symptoms, Causes and Implications” (2015) 7(3) Journal of Human Rights Practice 366. See also Paul Gorski and Cher Chen, “‘Frayed All Over:’ The Causes and Consequences of Activist Burnout Among Social Justice Education Activists” (2015) 51(5) Educational Studies 385).

Some studies point to the very nature of legal work as challenging for work-life conflict (eg ‘dropping everything’ for a client, constantly being ‘on call’, and a feeling of constant urgency, especially in a digitally connected world). Others point specifically to billing practices as a key contributor to stress and anxiety (and, ultimately, inefficiency) in law practice (see Colin James, “Legal Practice on Time: The Ethical Risk and Inefficiency of the Six-Minute Unit” (Alternative Law Journal, 2018),; Adele J Bergin and Nerina L Jimmieson, ‘Australian lawyer well-being: Workplace demands, resources and the impact of time-billing targets’ (2014) 21(3) Psychiatry, Psychology and Law 427.; International Bar Association, “Mental Wellbeing in the Legal Profession: A Global Study” (London, England: 2021); Nathalie Cadieux et al, “Research Report: A Study of the Determinants of Mental Health in the Workplace Among Quebec Lawyers, Phase II – 2017-2019”, Research Report, Université de Sherbrooke, Business School, 2020.) More about billing practices can be found elsewhere in the text.

Drinking and other drug use in the profession is also frequently noted as a problem, including troubling evidence that drinking is an “expected” part of being a lawyer. (See Debra Austin, “Drink Like a Lawyer: The Neuroscience of Substance Use and its Impact on Cognitive Wellness, (2015) 15 Nevada Law Journal 826.; G. A. Benjamin, E.J. Darling & B. Sales, The Prevalence of Depression, Alcohol Abuse, and Cocaine Abuse among United States Lawyers, 13 Int. J. L. Psychiatry 233 (1990),; C. Beck, B. Sales & G. A. Benjamin, Lawyer Distress: Alcohol-related Problems and other Psychological Concerns Among a Sample of Practicing Lawyers, (1996) 10 Journal of Law and Health 1).

Increasing evidence also points to the negative impact of discrimination (both individual and structural) in the legal profession on mental wellness. Notably, addressing anti-racism and other anti-discrimination measures as a mental wellness measure are absent from many (although not all) studies. The New York Bar Association noted the racial trauma that can result from discrimination in legal education and practice. Carter defines racial trauma as:

“Race-based events that may be severe or moderate, and daily slights or microaggressions, can produce harm and injury when they have memorable impact of lasing effect or through cumulative or chronic exposure to the various types or classes of racism. The most severe forms may not be physical attacks. In the section on physiological reactions to racism, blatant forms of discrimination were not often related to risk in heart disease risk, but rather more subtle acts were related to potentially harmful physical reactions” (R.T. Carter, “Racism and psychological and emotional injury: Recognizing and assessing race-based traumatic stress” 35 The Counseling Psychologist 13-105 at 89-90; International Bar Association, “Mental Wellbeing in the Legal Profession: A Global Study” (London, England: 2021); Richard Collier, “Wellbeing in the legal profession: reflections on recent developments (or, what do we talk about, when we talk about wellbeing?)” (2016) 23 International Journal of the Legal Profession 41.; Ronit Dinovitzer et al, “After the JD: First Results of a National Study of Legal Careers” (NALP, 2004). See also “After the JD II” and “After the JD III: Third Results from a National Study of Legal Careers”.)

In addressing structural approaches to mental wellbeing, the International Bar Association Presidential Task Force on Mental Wellbeing in the Legal Profession survey notes:

“many individuals have good self-care practices in place, but.. their mental wellbeing is being challenged by the structures and cultures in which they operate. The focus needs to be on the structure and cultural working practices within law which are problematic for mental wellbeing, and not on enhancing the ‘resilience’ of individual legal professionals.

These structural and cultural issues include:

– poor or non-existent managerial training, particularly in the area of psychological grown and the development needs of staff;

– a lack of basic mental wellbeing support, including specific measures to address PTSD and vicarious trauma;

– bullying, harassment, sexism and racism; and

– for some, the ‘up or out’ working culture, which equates success with unsustainable hours, hitting billing targets and ever higher pay, particularly for junior members of the profession (15-16).

Reflection Questions

- In your experience, what structural issues prevent mental health and wellness to be better understood in a) law school, b) the profession, c) the judiciary?

- What aspects of the pandemic posted additional challenges to mental health and wellness?

- What is “perfectionism”? How does law practice emphasize perfectionism as a positive trait, and what are its drawbacks (see, for example, the Globe and Mail article in the introductory section)?