5.5 Duty of Competence

Gemma Smyth

Duty of Competence

“Competence” arises in the minds of most students when entering one of their first workplace experiences. Many students feel unprepared or nervous, especially given the importance of the role a lawyer places in the lives of people. While “competence” is certainly a feeling, it also is a professional duty defined by Law Societies.

The LSO Rules addresses the duty of competence in a somewhat circular way, specifically: “A lawyer shall perform any legal services undertaken on a client’s behalf to the standard of a competent lawyer” (Rule 3.1-2, online: https://www.lso.ca/about-lso/legislation-rules/rules-of-professional-conduct/complete-rules-of-professional-conduct).

The Federation of Law Societies of Canada Model Code of Professional Conduct has a much more detailed definition of competence. It is reproduced here in its entirely.

3.1-1 In this section,

“Competent lawyer” means a lawyer who has and applies relevant knowledge, skills and attributes in a manner appropriate to each matter undertaken on behalf of a client and the nature and terms of the lawyer’s engagement, including:

(a) knowing general legal principles and procedures and the substantive law and procedure for the areas of law in which the lawyer practises;

(b) investigating facts, identifying issues, ascertaining client objectives, considering possible options and developing and advising the client on appropriate courses of action;

(c) implementing as each matter requires, the chosen course of action through the application of appropriate skills, including:

(i) legal research;

(ii) analysis;

(iii) application of the law to the relevant facts;

(iv) writing and drafting;

(v) negotiation;

(vi) alternative dispute resolution;

(vii) advocacy; and

(viii) problem solving;

(d) communicating at all relevant stages of a matter in a timely and effective manner;

(e) performing all functions conscientiously, diligently and in a timely and cost-effective manner;

(f) applying intellectual capacity, judgment and deliberation to all functions;

(g) complying in letter and spirit with all rules pertaining to the appropriate professional conduct of lawyers;

(h) recognizing limitations in one’s ability to handle a matter or some aspect of it and taking steps accordingly to ensure the client is appropriately served;

(i) managing one’s practice effectively;

(j) pursuing appropriate professional development to maintain and enhance legal knowledge and skills; and

(k) otherwise adapting to changing professional requirements, standards, techniques and practices.

…

[15] Incompetence, Negligence and Mistakes – This rule does not require a standard of perfection. An error or omission, even though it might be actionable for damages in negligence or contract, will not necessarily constitute a failure to maintain the standard of professional competence described by the rule. However, evidence of gross neglect in a particular matter or a pattern of neglect or mistakes in different matters may be evidence of such a failure, regardless of tort liability. While damages may be awarded for negligence, incompetence can give rise to the additional sanction of disciplinary action.

The Commentary to Rule 3.2 elaborates on competence:

[2] Competence is founded upon both ethical and legal principles. This rule addresses the ethical principles. Competence involves more than an understanding of legal principles: it involves an adequate knowledge of the practice and procedures by which such principles can be effectively applied. To accomplish this, the lawyer should keep abreast of developments in all areas of law in which the lawyer practises.

So, what is the standard of “competency”?

Law students often struggle with the idea of competence, especially because this duty is by its nature somewhat unclear. Certainly, the Commentary to the Federation Model Code does not set the bar at “perfection”! The competencies that underlie a “competent lawyer” are also challenging to clearly define. Again, competencies might overlap or might be entirely different at the various stages of a lawyer’s regulatory journey. Also note that the idea of “competence” is closely linked to “imposter phenomenon”, discussed later in this text.

While it is a good sign that a student takes their role seriously, students should also feel well- supported and well-supervised, such that stress regarding competence is not a barrier. In an externship and clinical context, students are both working and learning. It is healthy and appropriate to feel inexperienced and to seek supports to improve expertise. In all contexts, students are practicing under the license of their supervisor. As such, no legal advice should be given without the approval of a supervisor. A supervisor will provide feedback and support so no problem is on the student’s shoulders alone.

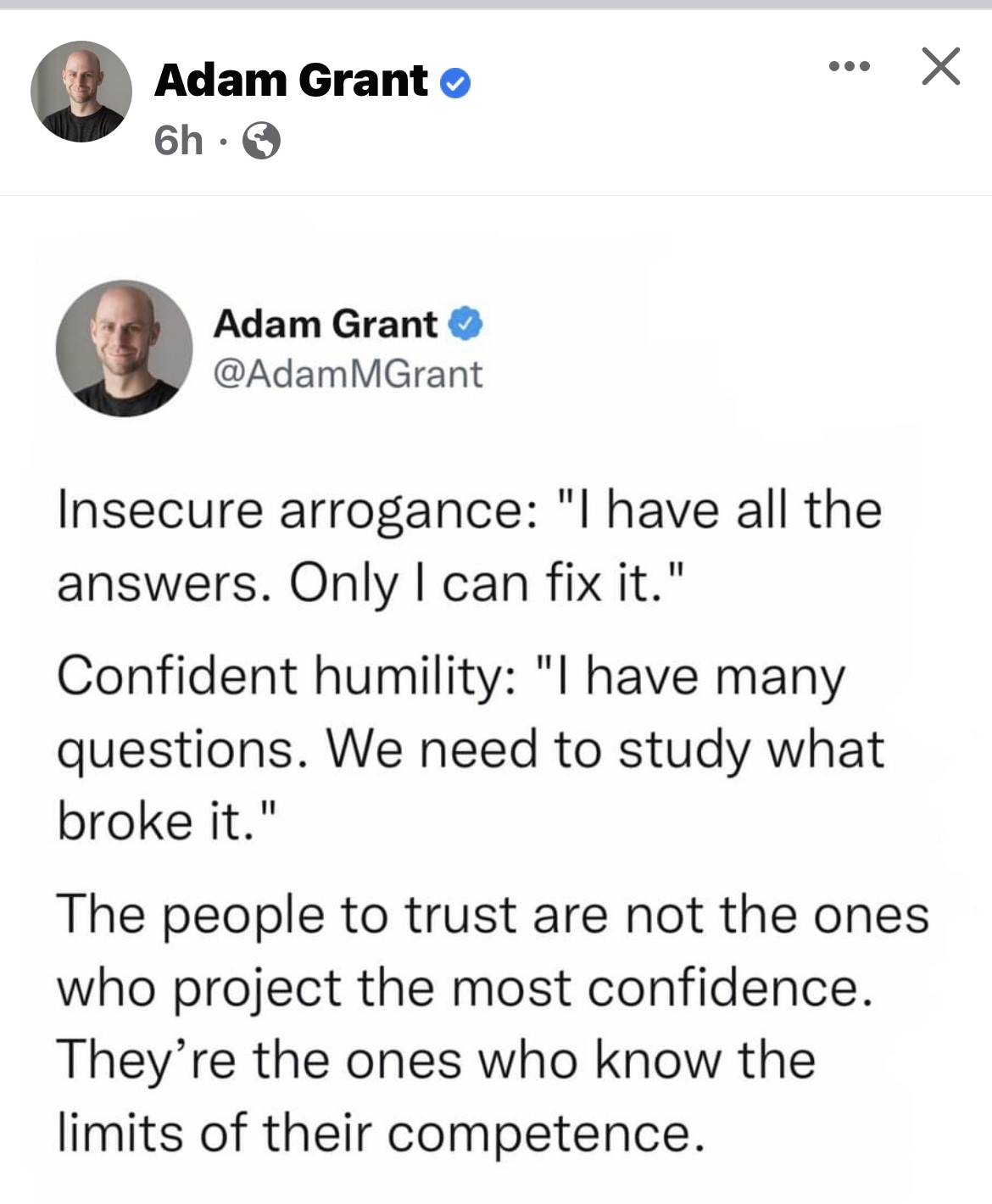

Instagram, @AdamMGrant, 2022.

The idea of “competence” in a professional context is not only an individual characteristic, but also one defined and managed by a collective – the professional group to which a professional belongs. Wenger-Trayner notes:

“In the sense used here, competence includes a social dimension. Even as manifested by individuals, competence is not merely an individual characteristic. It is something that is recognizable as competence by members of a community of practice. A regime of competency is not static, however. It shapes personal experience but can also be shaped by it. It is both stable and shifting as it lives in the dynamic between individuals’ experience of it and the community’s definition of it. Indeed, competence and experience are not a mere mirror-image of each other. They are in dynamic interplay. Members of a community have their own experience of practice, which may reflect, ignore, or challenge the community’s current regime of competence… When newcomers are entering a community, it is mostly the regime of competence that is pulling and transforming their experience – until their experience reflects the competence of the community. This is what happens in apprenticeship, for instance. Conversely, experience can also pull, challenge, and transform the community’s regime of competence. A member can find a new solution to a problem and attempt to convince the community it is better than existing practice.” (14)

As the author notes, novice members of a profession also have impact on regimes of competence. For example, cultural competence was traditionally not recognized as an important part of professional lawyering practice, but has increasingly been understood to be extremely important.

Reflection Questions

- What areas of practice do you feel most inexperienced in? This could include the law itself, client interactions, workplace ‘ways of being’, or other area – or all of the these!

- Consider: a client asks you to give them an opinion on their legal matter during an interview. What do you do? Would it make a difference if the client was asking for legal information rather than legal advice?

- If you were to think of your own impact on how competence is seen in the legal profession, what changes would you like to see over your career?