12 What is racism?

Racism is broad and complex in its definition! It can present in multiple, pervasive ways and in interpersonal, individual, and systemic contexts.

Merriam-Webster defines racism as:

Here, we see racism as inherently linked to projects of eugenics (which refers to Francis Galton’s theorizing around breeding and reproducing “good genes” in an attempt to create an “ideal” white, able-bodied society), colonialism, imperialism, and indentureship, where racialized persons have been violated, oppressed, marginalized, violently displaced, abducted, murdered, tortured, and forced into violent practices of white supremacy (e.g. genocidal institutions, slavery, etc.) based on claims that race is a “science” or a product of inherent, biological differences. However, ongoing work from racialized scholars, activists, theorizers, scientists, and their allies have disproven these claims and pointed to the ways in which race is a social construct. For example, research from Richard Lewontin, a geneticist from the 1970s, indicates that 85% of human variation can be found within any local population, meaning that the human species is much more similar than we appear. In other words, perceived differences on the basis of race are informed by social construction, not by biological difference.

Although race is a social construct, the impacts of racism are real, tangible, historical, and ongoing. Beliefs about white superiority continue to govern social institutions, structures, and spaces that we work and live within as they are built on foundations of white supremacy and racism. For example, many common practices in our western educational upbringing, including standardized testing, “IQ,” what counts as “real” or “reliable” knowledge, and the ways in which learning is facilitated (e.g. in classroom structure and lecture formats), were built on beliefs about naturalized intelligence, whiteness, and Eurocentric epistemologies. Here, racism extends beyond “belief” into material actions and ideologies that continue to shape our contemporary experiences.

Racism can be experienced on multiple levels and in interrelated contexts, including:

- Personal/individual (e.g. internalized racism, traumatic responses, personal beliefs and prejudices, etc.)

- Interpersonal and Intracommunal (e.g. microaggressions, racism occurring in interactions with others, racial slurs, etc.)

- Systemic (e.g. unsafe workplaces, classroom spaces, community spaces, etc., where racism is built into the policies and practices of the organization)

- Structural (e.g. patterns of racism across institutions and organizations embedded within common policies, practices, structures, etc.)

- Poststructural (e.g. the intersections and interconnections of systems of oppression, including racism’s interactions with cisheteropatriarchy, capitalism, etc. that facilitate experiences of racism)

- Historical/Intergenerational (e.g. experiences of racism that have material and historical origin, such as legacies of colonialism and its continued violence, oppression, and marginalization of Indigenous communities)

What is racism?

While there are numerous definitions and attempts to visually represent racism and its various levels, it is important to note that these understandings are dynamic, contextual, and evolving. Race, itself, is a social construct that was historically designed to justify practices of white supremacy and in an attempt to depict white people as inherently superior to Black, Indigenous, and racialized persons. While race is a social construct, we must also recognize that it maintains tangible and material implications for how people are able to move and gain access to a multitude of rights, privileges, liberties, spaces, and places, which is due to the centralization, protection, and power of whiteness

While there are numerous definitions and attempts to visually represent racism and its various levels, it is important to note that these understandings are dynamic, contextual, and evolving. Race, itself, is a social construct that was historically designed to justify practices of white supremacy and in an attempt to depict white people as inherently superior to Black, Indigenous, and racialized persons. While race is a social construct, we must also recognize that it maintains tangible and material implications for how people are able to move and gain access to a multitude of rights, privileges, liberties, spaces, and places, which is due to the centralization, protection, and power of whiteness

How Whiteness Operates

Part of what makes whiteness so difficult to identify, name, and challenge within academia is its ability to remain invisible to white educators, practitioners, and students, thus permeating physical and intellectual spaces and utilizing its normative structure to protect itself from redress. Yee and Dumbrill (2003) refer to these dynamics as:

- exnomination, or the ability of whiteness to go unnamed,

- naturalization, or the ability of whiteness to name the ‘Other’ and not itself, and

- universalization, or the ability of whiteness to ingrain a western, Eurocentric understanding of a given problem as the only true perspective.

In predominantly white institutions (PWIs), where the majority of faculty, instructors, senior administrators, and – in some cases – students are white, where the curriculum is structured and approved by other PWIs, and where the majority of course content is authored by white academics, whiteness becomes further entrenched, thus leading to “colour-blind,” spatial and curricular walls protecting and reinforcing a pedagogy of whiteness. Here, while white folks can see themselves represented in curriculum, many racialized students cannot.

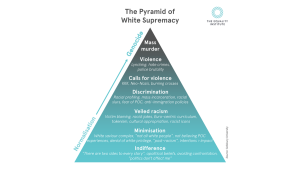

Pyramid of White Supremacy

While it can be difficult to recognize and understand, racism can be perpetrated intentionally and unintentionally and can appear in both explicit, identifiable ways and implicit, invisible ways. The Equality Institute’s Pyramid of White Supremacy attempts to depict the ways in which the normalization of racism can actively facilitate and justify white supremacist violence in its most extreme forms.

While it can be difficult to recognize and understand, racism can be perpetrated intentionally and unintentionally and can appear in both explicit, identifiable ways and implicit, invisible ways. The Equality Institute’s Pyramid of White Supremacy attempts to depict the ways in which the normalization of racism can actively facilitate and justify white supremacist violence in its most extreme forms.