19 Pedagogical Barriers to Change

Part of what facilitates educational barriers to creating safer classrooms is the implicit or explicit centering of whiteness, which involves both pedagogical decisions and impulses to focus on white folks’ identities, feelings, reactions, and experiences during discussions of racism.

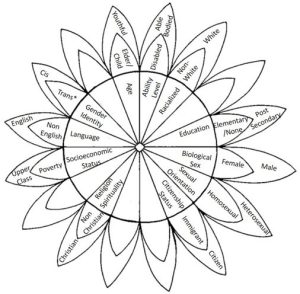

Centering your own feelings often happens in an attempt to distance oneself from racism and/or to deflect discomfort, anxiety, and anger. Razack refers to these dynamics as “flights/moves to innocence.” When discussing racism in a classroom setting, many white instructors turn toward activities and conversations that seek to understand identity, privilege, and power on a microlevel, such as through activities like “the power flower,” “the privilege walk,” and the social identity wheel. A popularly used example is Peggy Macintosh’s “Knapsack of White Privilege,” where white folks are called to individually pull apart and examine their experiences as it relates to a list of statements.

Though these activities operate in an effort to introduce people to concepts like social location and power and can be a good entry point for white students, they often create arbitrary, binary, and static categories of identity that are separate and distinct from each other when, in reality, they are interwoven, interlocking, and borne from the same systems of oppression. While many white students might have eye-opening experiences during these discussions, many marginalized students are often left feeling uncomfortable, frustrated, and put on the spot. As participants in our focus group suggested, these activities are reductive, essentializing, and facilitate the possibilities of the “Oppression Olympics,” where groups of people are pitted against each other and experiences become comparative, competitive, and hierarchically ordered.

Example

IMAGE: An example of the “power flower” activity, where participants locate themselves either “inside” or “outside” the flower petals for each category of identity marker. “Inside” positions refer to identities of privilege and power, such as whiteness or heterosexuality, while “outside” positions refer to identities of marginalization, such as racialization or queerness.

These activities fail to account for the ways in which white queer folks’ experiences will be fundamentally different than racialized queer folks’ experiences, despite them occupying a similar “category” in the wheel or flower.

Whiteness

It is important to understand that white privilege, white fragility, white tears, and white rage, which often contribute to the centering whiteness and catering curriculum to their experiences, are not things that can be simply and individually “unpacked” or challenged; rather, the “nature of privilege is such that it cannot be worked through at an individual level […] because it is a process that is still fundamentally about [white students]”. Additionally, hyperfocus on “privilege” might passively depict racist dynamics and take away from the realities of “power.” While white folks can certainly challenge these defensive reactions, discomfort, urges to lash out, and efforts to (re)centre their own identities on a microlevel (e.g. in interpersonal dynamics and personal reflections), there must be a constant recognition of the systems and structures that facilitate these experiences and that, by virtue of proximity to whiteness, white folks benefit from and uphold these systems as they currently operate on foundations of whiteness, racism, and colonialism, among other interwoven social forces.

Beyond centering whiteness through exploratory activities that essentialize and silo identities,

Participants in our focus group and in the projects that came before us identified additional barriers, including:

- Out-of-date syllabi, course content, readings, lectures, and videos. For example, some courses might use readings that are not cognizant of the current and ever-evolving sociopolitical context and burgeoning theorization about race, racism, and racialization. In this process, many racialized students may feel unrepresented in course content and, therefore, disengaged from the course.

- Additionally, some courses may be using content that is violent or harmful. For example, some classes continue to use readings that deploy harmful language (e.g. racial slurs or out-of-date terminology) and some videos may show graphic depictions of racist violence. Much of this information is presented without content warnings and/or safety planning for students who may be affected, and frequently remain in course syllabi despite student feedback indicating it is harmful.

- The failure to establish group guidelines or safety considerations before facilitating class discussions. Group guidelines act as a social contract between and among instructors and students to explore how the classroom can be a respectful learning environment that everyone feels comfortable participating in.

- The implicit (or explicit) demands placed upon racialized students to educate classmates about racism, which might happen when the instructor is unprepared to field difficult questions about race, identity, and power and/or open up class discussion/debate during “difficult dialogues.”

- Reactive and defensive responses to students’ concerns that dismiss their feedback, emotions, and needs, which might include refusing to apologize, avoiding conversations with students, and a failure to address the concern clearly and intentionally.

- The centralization of Eurocentric epistemologies might frame each course theme and concept through a whitestream lens, where whiteness becomes the primary vehicle for knowing and race, racism, and racialization become tertiary or elective. Here, there is a distinct failure to integrate critical race understandings, which then might impact assignment creation and assessment practices that do not recognize non-Western ways of knowing, doing, and being.