13 How racism occurs in the classroom and how you may be perpetuating it

Students play an intricate role in cultivating classroom climates that are conducive to open sharing, vulnerability, and mutual respect.

How racism happens in the classroom (and the role you play!)

Prelude: Embrace Discomfort!

While it can be difficult to accept, it is very likely that we, as non-racialized people, perpetrate, uphold, excuse, and/or benefit from racism in our daily lives. As racism is built into the fabric of the institutions and spaces that we live and work within, we often reap the benefits of these systems, practices, policies, and structures. For example, when western academia is predicated on Eurocentric epistemologies, when our university’s upper administration is predominantly comprised of white folks, and when research has proven the ways in which white candidates are more likely to be hired in a workplace compared to their racialized counterparts, white people are afforded privileges, liberties, advantages, and opportunities that racialized folks are not. Furthermore, because the systems we operate within are built on racist beliefs and ideologies, much of what we have learned through socialization, education, and upbringing and what we value, believe, and communicate might uphold, perpetuate, and/or justify foundational and historical racism. For example, elementary and secondary school education in Canada often fails to accurately describe the colonial violence perpetrated by settlers against Indigenous peoples and, instead, euphemizes the “discovery” and “creation” of Canada as a “peaceful” relationship between white settlers and Indigenous communities, which is still reflected in popular and patriotic discourses of Canada as a “multicultural” and “peacekeeping” nation.

This realization that we may have committed or contributed to racism can be deeply uncomfortable, distressing, and challenging as it may disrupt what we know and/or believe about ourselves, our identities, and the spaces we live in. Many white folks have the urge to proclaim “I’m not racist!” when confronted with the historical and temporal realities of white supremacy, racism, and violence. However, we urge you to sit in the discomfort of knowing that racism is inextricably linked to whiteness. This is not in an effort to shame or blame you; rather, it’s an entry point to better understanding the origins of these issues and how we contribute to them as this will form the basis of understanding how we can challenge and change things. In other words, we cannot pursue change without fully appreciating the complexities and nuances of these issues.

Racism can happen in many ways in the classroom.

As this is a space where students, TAs, and instructors gather to discuss and examine complex social issues, the classroom is reflective of our lived experiences outside of school. In other words, dynamics in the classroom are not siloed from experiences in the greater community; rather, the classroom simulates, recreates, and reifies social and societal dynamics. In this way, racism can be replicated in discussions, course content, and class structure, where racialized students may feel silenced, dismissed, scrutinized, excluded, and/or violated in ways that are similar to their experiences outside of the classroom. Conversely, white students may hold power, privilege, freedom, and control in class dynamics where, similar to dynamics in the community, their ideas, contributions, and participation are valued and celebrated at the expense of racialized folks in the room.

Additionally, white students’ learning is often prioritized, regardless of the potential impacts it might have on racialized students. What a white student sees as a “great learning experience” might have been perceived by a student of colour as something that was unsafe, harmful, and unsettling. While the white student leaves class feeling empowered and excited by the new knowledge they acquired through a discussion or debate, the student of colour leaves class feeling angry, upset, unsafe, and isolated. It is important to understand that it can be draining, intimidating, and incredibly challenging for racialized students to educate others, defend themselves, and/or participate actively in a discussion about racism, power, oppression, and the topics that intersect with these issues, even when you feel like it’s an interesting and engaging dialogue. Here, we see class dynamics as playing out very differently depending on your identities and lived experiences.

The most common form of racism that students of colour identify as happening actively in the classroom are microaggressions.

Microaggressions are commonplace, daily, implicit, and explicit verbal, behavioural, and/or environmental expressions of harm that are hostile, derogatory, and negative in nature toward a person or group of people. They are the most cited “type” of racist behaviour and interaction that occurs in social settings. Microaggressions can be perpetrated intentionally and/or unintentionally, knowingly or unknowingly. Microaggressions take on various manifestations, ranging from allegedly “well-meaning” comments about racialized students’ intellect, identity, and appearance to “straight-up aggression.” However, they maintain similar impacts on racialized students, including feeling embarrassed, angry, distressed, and unsafe.

In addition, microaggressions:

- precipitate “difficult dialogues” in the classroom about identity, racism, and power,

- involve various responses from racialized students that can be cognitive, emotional, and/or behavioural, which are shaped by both student peers’ and instructors’ traits and identities (e.g. can be exacerbated by racialized students feeling alone, isolated, and/or underrepresented in the classroom and its curriculum),

- rely upon and communicate stereotypes and assumptions about specific groups of people or racialized communities more broadly, regardless of delivery and intent,

- implicitly and explicitly demand that racialized students educate others about their identities and experiences through disclosure, tokenization, and being ‘put on the spot’ (e.g. asking a racialized student a question about their identity and expecting them to answer on behalf of that identity marker),

- bemoan the “racial agenda” and assume that racialized students’ accounts are untrue (e.g. “why are they always playing the race card?”),

- facilitate unchallenged surveillance, scrutiny, and questioning of racialized students (e.g. commenting on and making judgments about racialized students’ responses and reactions to things happening in the classroom),

- are imbued within curriculum, pedagogy, and the classroom structure, and result in cultural misrepresentation, misappropriation, and erasure,

- are often met with (white) instructors’ and student peers’ silence and complicity in failing to intervene,

- seek to dismiss and invalidate racialized students’ reactions to them, and

- operate to further isolate and marginalize racialized students and facilitate poor physical, mental, cultural, and social health outcomes.

Many white students may inadvertently or purposefully communicate microaggressions while participating in their classes. It can be an uncomfortable realization; however, recognizing what microaggressions look like and their impacts on racialized students are significant first steps toward challenging and changing these practices in meaningful ways.

Examples of Microaggressions

Exclusion: Being marginalized, not to be made welcome, and to be made to feel out of place

-

- E.g. folks refusing to sit or engage with racialized students, choosing racialized students last for group projects, saying “Oh, I don’t think this group is for you”

Dismissal: This usually occurs when a microaggression has taken place as racialized person attempts to address it. Gaslighting emotional responses and attempts to invalidate or dilute the experience is typically underpinned by dismissal

-

- E.g. “You’re just being too sensitive”, eye-rolling and heavy sighs, “you’re always so difficult,” “You’re making such a big deal of this”

(Mis)appropriation of points: Falling under the larger category of cultural appropriation, (mis)appropriation of points often occurs in the classroom and is better known as “stealing intellectual property.” This often happens when BIPOC students put forth points in smaller group settings and sidebar conversations with faculty, where their thoughts, points, and contributions are verbally plagiarized, stolen, and/or misrepresented by white students, TAs, instructors, and/or faculty

-

- E.g. a racialized student answer a professor’s question in class and a white counterpart states the same fact afterwards; the racialized student’s point is not acknowledged, while the white counterpart’s is applauded

“Devil’s advocate”: Playing devil’s advocate usually occurs in a discussion or debate where another party expresses an opinion, that they may or may not agree with, but is very different to what other people have been saying. The goal of these contributions is often framed as an effort to make the argument/discussion more “interesting.” Often, folks use the devil’s advocate trope for the “love of debate,” to “engage in a critical discussion,” or to “offer other viewpoints and perspectives.” While varying perspectives are important to learning, the devil’s advocate frequently introduces ideas that are invalidating, dismissive, and inflammatory to elicit a heated dialogue about contentious topics, including racism. This often occurs for BIPOC students in spaces where they are speaking to and addressing topics of race, racism, and racialization. The devil’s advocate then publicly attempts to invalidate and question the person’s point for educational, intellectual, and social gain.

-

- E.g. “I mean, I don’t feel this way, but it’s important to consider…,”

- E.g. “Not to play devil’s advocate, but…”,

- E.g. “I don’t know if that’s necessarily true because I read/saw/heard…”

Silencing: This can be considered another form of invalidation and marginalization, often experienced by students of colour and deployed in order to stop them from expressing their views and points.

-

- E.g. talking over and interrupting, stating that it’s not the “time of place for this conversation,” “parking lotting” the conversation and never returning to it

Uncompensated labour: This is an interactive experience where BIPOC students have to educate, address, soothe, and provide resources for white counterparts on topics on race, racism, and racialization. This usually happens in classroom settings when BIPOC students have to defend their race and/or identities, address racist discourse in the class, intervene in harmful conversations, and/or self-disclose to educate the group

-

- E.g. consoling white counterparts’ emotional reactions to topics of race, clarifying stereotypes applied to particular races, disclosing personal experiences to “prove their point,” consoling and therapizing other BIPOC students after harmful and unsafe incidents in the classroom

Explicit discrimination and harm: These are usually overt and aggressive racist and discriminatory interactions

-

- E.g. depicting harm on BIPOC bodies for learning examples, outright racial slurs, threats of violence based on race, anonymous racists posters and marketing, instances of racial profiling on campus

White Fragility, White Rage, and White Victimhood

As we briefly mentioned before, many white folks often have the urge to distance themselves from racism and may fear being labelled “racist.” Here, the term “racist” is frequently framed as a slur against white folks and as something that can damage one’s self-image or social reputation. The difficult truth is that, by virtue of one’s proximity to the material, historical, and temporal system of whiteness, white folks contribute to and benefit from institutionalized, systemic, and structural racism, which often becomes identifiable in interpersonal interactions. However, many white folks can deploy strategies of attempting to rebuke, dismiss, manage, or cope with the realities of their own racism and/or their links to racism. For example, terms like “white fragility” have been used to describe white folks’ emotional, defensive, angry, and dismissive reactions to being called out or called in for engaging in racist practices. You may have also heard the term “white tears” or “white guilt,” which allude to the ways in which white folks (re)centre their own emotions, cling to a sense of victimhood, and burden racialized folks with responding to and/or absolving their own guilt for historical and contemporary racism. What we particularly want to emphasize is the importance of “white rage”: while many white folks prefer to identify with passive terms that centre emotion, guilt, and conscience, the realities of white supremacy and its violence indicate that most reactions to being called out for racism reify and perpetuate racism through anger and defensiveness resembling violence or threats of violence. Only focusing on “fragility” and “guilt” might distract from the tangible, material, and lived implications of “white rage.”

Rather than quickly, swiftly, and decisively denying our own racist beliefs, prejudices, and practices or cling to what Razack calls “flights/moves to innocence” (e.g. attempts to excuse racist beliefs and actions), we should consider sitting in the discomfort of our roles in recreating and protecting racism. From there, we can then think about tangible ways to change these beliefs and behaviours.

As it pertains to students’ experiences in university classrooms,

‘Racist/racism’ is not a term that white folks should shy away from or actively reject; rather, it is an entry point to understanding that racism is imbued within the structures, organizations, and spaces that we operate, live, and work within and that we can enact these systems in our everyday lives. Feeling comfortable, safe, and able to engage in “difficult dialogues” about race, identity, social location, and power is differently defined based on one’s proximity to whiteness and “dominant” social positionings. The table below summarizes the major findings in a 2014 study by Garran and Rasmussen, where students in “dominant” positions (e.g. those who are white, able-bodied, cisgender, heterosexual, etc.) and “non-dominant” positions (e.g. those who are racialized, disabled, trans, queer, etc.) were asked to describe what “safety” looks like for them in the classroom:

|

Students in “dominant” positions

|

Students in “non-dominant” positions

|

Here, we can see that students from non-dominant positions are deeply concerned about being tokenized, put on the spot, forced to educate others, framed as overly sensitive or emotional, homogenized, and stereotyped through microaggressive assumptions and comments from peers and instructors. In contrast, students from dominant positions expressed concern about being attacked, judged, or framed as “racist” after “making a mistake.” In other words, while dominant students fear being called out for their class contributions and/or being labelled as “racist,” non-dominant students fear experiencing racism and feeling unable to contribute to class dialogues at all.

We want to make a distinction here: there is a difference between feeling “unsafe” and feeling “uncomfortable.” While discomfort certainly can be a symptom of a lack of safety, the discomfort we are discussing refers to having our values or beliefs challenged in a thoughtful, respectful, and specific way. For example, when we learn about the realities of colonial violence, anti-Black racism, and other forms of racism, we may feel uncomfortable: e.g.) thinking about our own whiteness, how we might contribute to these issues in a contemporary context, how we might have been taught false things about these issues, etc. When we hold a belief that is proven to have racist origins or links, we might feel troubled, distressed, guilty, sad, or concerned. These are normal feelings that are part of active learning and can push us to a place of better, more inclusive, and more fulsome understandings of social problems. However, when a racialized student is told that “race is biological,” their experiences “aren’t real,” they are “too sensitive” during conversations about racism, or they should give an “example” to “prove their point” about racism, they might feel unsafe: e.g.) distressed, scared, excluded, violated, scrutinized, tokenized, put on the spot, and unwelcome. There is a key difference here: while discomfort can move us forward in our learning, feeling unsafe can hold us back; racialized students who feel unsafe might feel like they cannot return to class, participate actively, or be successful in their education at all. When white folks equate their own discomfort with a lack of safety, they might perpetuate some of the things that Garran and Rasmussen identified in their study, such as suggesting that being called “racist” is the same as experiencing racism (when, in reality, it’s not!).

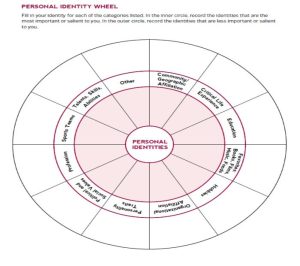

Part of what facilitates this dynamic is the ways in which white folks may centre themselves, their identities, their feelings, their reactions, and their experiences during discussions of racism, often in an attempt to distance themselves from racism or to deflect their discomfort, anxiety, and anger. Razack refers to these dynamics as “flights/moves to innocence.” There is frequently an attempt to then understand whiteness as it pertains to microlevel experiences and individual identity markers, such as through activities like “flower power,” “the privilege walk,” and the social identity wheel. A popularly used example is Peggy Macintosh’s “Knapsack of White Privilege,” where white folks are called to individually pull apart and examine their experiences as it relates to a list of statements. Though these activities operate in an effort to introduce people to concepts like social location and power, they often create arbitrary, binary, and static categories of identity that are separate and distinct from each other when, in reality, they are interwoven, interlocking, and borne from the same systems of oppression. As participants in our focus group suggested, these activities are reductive, essentializing, and facilitate the possibilities of the “Oppression Olympics,” where groups of people are pitted against each other and experiences become comparative, competitive, and hierarchically ordered.

Personal Identity Exercises

IMAGE: An example of the “identity wheel” activity, where participants locate themselves either “inside” or “outside” the flower petals for each category of identity marker. “Inside” positions refer to identities of privilege and power, such as whiteness or heterosexuality, while “outside” positions refer to identities of marginalization, such as racialization or queerness.

IMAGE: An example of the “identity wheel” activity, where participants locate themselves either “inside” or “outside” the flower petals for each category of identity marker. “Inside” positions refer to identities of privilege and power, such as whiteness or heterosexuality, while “outside” positions refer to identities of marginalization, such as racialization or queerness.

These activities fail to account for the ways in which white queer folks’ experiences will be fundamentally different than racialized queer folks’ experiences, despite them occupying a similar “category” in the wheel or flower. The activity does not account for the ways in which whiteness operates visibly to advantage white folks.

Challenging Microlevel “Unpacking”

It is important to understand that white privilege, white fragility, white tears, and white rage, which often contribute to the fear, defensiveness, and anger about being called “racist,” are not things that can be simply and individually “unpacked” or challenged; rather, the “nature of privilege is such that it cannot be worked through at an individual level […] because it is a process that is still fundamentally about [white students]”. While white folks can certainly challenge these defensive reactions, discomfort, urges to lash out, and efforts to (re)centre their own identities on a microlevel (e.g. in interpersonal dynamics and personal reflections), there must be a constant recognition of the systems and structures that facilitate these experiences and that, by virtue of proximity to whiteness, white folks benefit from and uphold these systems as they currently operate on foundations of whiteness, racism, and colonialism, among other interwoven social forces. Again, this can be challenging to accept, but it also helps us in understanding that this is an issue much larger than us, as individuals.