Chapter 10 – Seasonal Wheel

The Kwakwaka‘Wakw Ebb and Flow of Life

Gwixsisalas Emily Aitken

One of the most influential messages that Indigenous Knowledge carries for all of us is to create and sustain bonds of kinship with the place where we live—the land, rivers, forest, oceans, water, rocks, fire, and air around us. The berry-picking season, the return of the salmon, the birth of a child, the blossoming of wild crabapples, are just a few examples of natural events that humans celebrate through dance, music, ceremony and stories. Every place has its own set of seasonal events that nature unfolds every year, and creating a seasonal wheel is one of the easiest and most effective teaching tools to help students have a relationship with their home-place. Developing a seasonal wheel is a highly adaptable project suited for classes of various sizes, grade levels and cultural backgrounds.

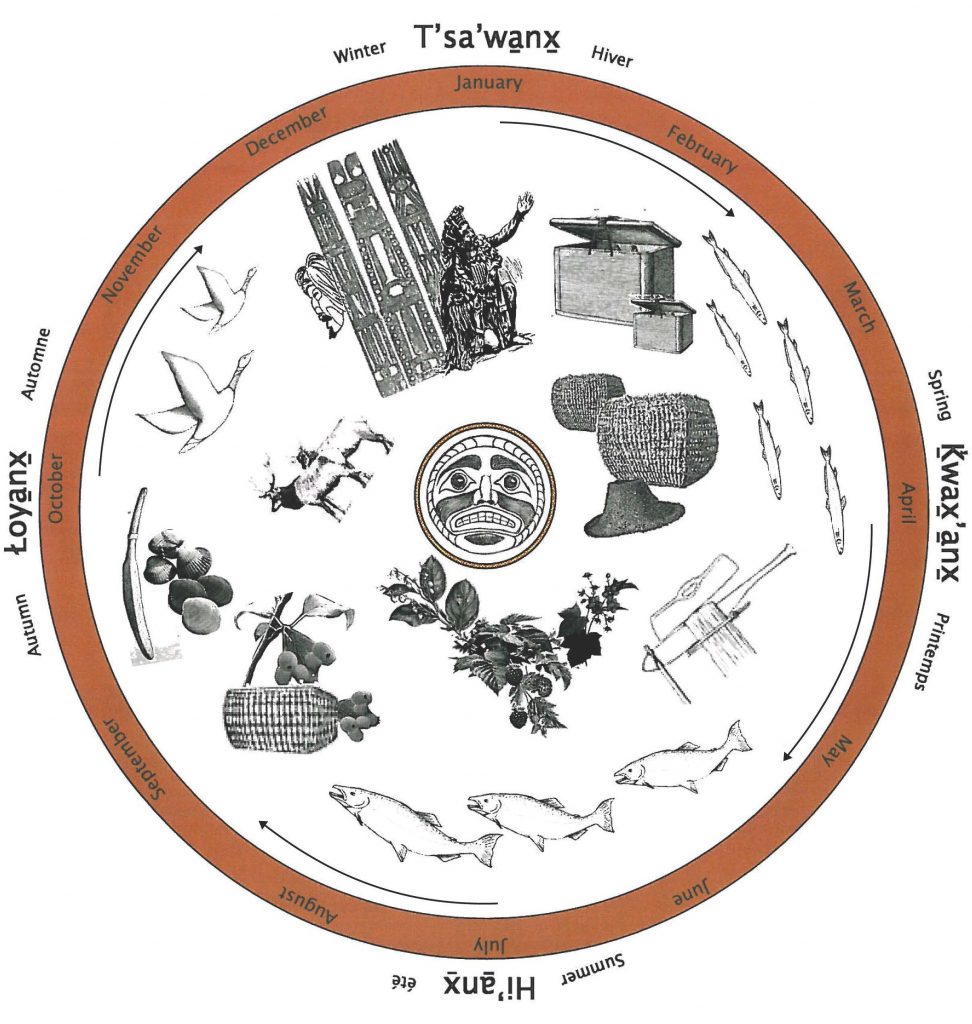

A Kwakwaka‘wakw Seasonal Wheel

A Kwakwaka‘wakw seasonal wheel includes four seasons, which in Kwak’wala is mu’anx. Within the seasons is a specific time for what is being harvested such as wa’anx (herring season). A‘ant (herring roe) is gathered when the herring spawn, either on saya’sa wawadi (kelp hair)—the old ones referred to herring on kelp as kaxk’alis a‘ant—or on hemlock or cedar branches purposely placed along the shore or anchored directly in the midst of the spawning area. The gathering and drying of an important seaweed łak‘axstan (red laver) takes place during the middle of spring. The harvesting of łak‘axstan corresponds with the arrival of the first sac’am (spring salmon). It is then that the fishing season starts and all the other species of fish follow: the małik (sockeye), hǝnun (pink salmon), gaxwa (steelhead), and p’o’i (halibut). Many other sea creatures are harvested over the spring, summer and fall, such as am’dama (small sea urchin), a‘las (red sea cucumber), and k‘umis (red rock crab).

One of the important shellfish gathered during the spring and fall is gawiq̓anǝm (butter clam) and the act of gathering clams is gagawiqa. Clams were kumaci (smoked) or steamed in the shell just as they are now. Many other plants and animals were and continue to be harvested for nourishment, shelter, clothing and art.

The winter was a quiet time of not having to gather and prepare for the winter months, and was a time for celebrating. There were feasts centred on specific foods to celebrate the wealth of the harvest. Of those feasts, the two most important were the t’łinagila (oolichan grease feast), where it continues to be given to the guests (literally “oolichan grease getting”), and t’alsila (high bush cranberry feast), where it is given to the guests (“cranberry getting”). The cranberry feast is no longer celebrated because our bogs have been drained or filled to such an extent that wild cranberries are no longer abundant. Yewixila laxa c’a‘wanx (going to the winter, “giving season”) is how the old people announced the ceka, now referred to as a potlatch. The ceka was most likely the highlight of c’a‘wanx (giving season) as it was a time for giving away much of what is owned, if not all. There were other feasts called k’wiła (splitting apart or dividing) such as a naming ceremony for a baby and for some tribes it was when the baby reached the age of ten months. The marriage ceremony in Kwak’wala, called kadzitła, most often happened at the same time as the winter ceremony.

Seasonal wheels might show how much or how little the seasons may have shifted and this can be illustrated with more than one wheel of the same area from different years. Perhaps if one was to create a seasonal chart for the past two years, the wheel might be quite different from the previous year’s wheel, especially dzaxwila, the time of harvesting oolichan. Still, the one constant for all the nations of the Kwakwaka‘wakw, no matter where they live, is that they have harvested oolichans at Dzawadi (Knight Inlet) since time immemorial.

The seasonal wheel in Figure 10.1 includes the plants and creatures of the ocean, the beach, the river and the forest. Information that informed the seasonal wheel came from tape recordings and written documentation of a generation of Kwakwaka‘wakw people born in the late 1800’s to early 1900’s, from research by Turner and Bell (1973), the Kwakiutl District Council, and Turner (2005), from other charts gathered throughout the years and from researching the writings of George Hunt and Franz Boas (1921, 1930).

Developing a seasonal wheel is a good way to introduce the medicinal plants of a home-place. There is an abundance of medicinal plants utilized by the Kwakwaka‘wakw. One of the most commonly used plants even to this day is pans’ani laxa xak’wama yasa mumuxwda’ams (gum from the bark of the balsam tree), which is used as a cure-all tea. Those who harvest these medicinal plants and prepare them for use believe that medicinal plants are sacred, and the harvesters do not share their craft unless they are mentoring the next generation of medicine practitioners. It would be wonderful for students to have a general idea of the best time for harvesting specific plants and how to make selected medicines.

The original Figure 10.1 of the Kwakwaka‘wakw Seasonal Wheel was poster-sized and was developed for use with groups of students or with the whole class. Once your students have collected information related to a local Aboriginal culture, you can use chart paper to modify the poster in specific ways to depict animal life or plant life from the forest, ocean or an inland water source. When creating a seasonal wheel, both languages (Kwak’wala and English) could be used, but start with the Indigenous way of marking seasons and then add the English. A lesson could include comparing the differences between bakwam (Indigenous Science) and Western Science, and what is common to both.

One of the most important “plants” of the Kwakwaka‘wakw that is not depicted in Figure 10.1 is the red cedar tree. There is a cycle for harvesting various parts of the tree depending on the tree’s location and elevation on the mountain. In the spring, when the sap runs, is the time of bark stripping and the gathering of its roots. When the ground is dry in late summer and fall, red cedar roots continue to be harvested. The time for making cedar baskets is during the winter months when rain or snow storms blow. A wheel could be created for all the plants on land and sea used by the Kwakwaka‘wakw with a focus around the red cedar to see the seasonal patterns of life.

Create Your Own Seasonal Wheel

When collecting information for a seasonal wheel, you need to decide what kind of information you want to include and then observe the course of nature and collect the required information. Engage your students in observing nature firsthand and keeping a field notebook to record changes in plant growth, animal migrations, or harvesting times over the course of several weeks or months. You might want to have students interview Elders and knowledge keepers, or invite a knowledgeable Elder into the classroom. When not observing in real time, the students could conduct research on the internet or in local cultural archives to find information on the same topic from years past. Once the class has collected the appropriate information, draw a large circle on chart paper or on the blackboard. Engage the students in discussion, and from the students’ comments, place the information on a circle or wheel.

Seasonal wheels can be made to illustrate traditions and ceremonies practiced by an Indigenous family or nation. Ask the students which seasonal traditions they observe, and record their answers on a chart. What kinds of traditions or activities do they do once a year? What do they do in the spring, summer, fall and winter? Why are these activities important? If possible, read aloud a story that illustrates seasonal traditions practiced by an Indigenous family.

Seasonal wheels can be made by all age levels from preschool, throughout middle school and high school. Preschoolers and elementary school students could make a seasonal wheel of the fun things they do during the different times of the year: camping, fishing, swimming, checking trap lines, ice fishing, sledding or carving masks. Photographs of students engaged in these activities add interest and excitement for preschoolers and beyond. Teachers could, with the help of language teachers, add words in the appropriate Indigenous language, and engage the students in speaking the language.

A fun project would be to have each student create his or her own seasonal wheel of the things they do over the year. Remember to always include the year, or create a whole new wheel for each year, recording the life and interests of the students. It’s a project that could continue throughout the life of a child. What a great legacy for future generations!

Teachers could make a large mural-sized project of the local community involving an entire class or school and display it in the school or community centre hallway or large wall, or posters could be made by different grade levels.

Seasonal Wheels Depicting Cycles of Nature

Becoming familiar with the local patterns of natural events gives people a greater appreciation of the importance, uniqueness and beauty of their home-place. The best source of information is nature herself. Watching her for an entire annual cycle or two will help sort out what kinds of topics to include in your seasonal wheel. Teach the students to keep their eyes, ears, and noses attuned to the sights, sounds, and smells of nature.

If you live by the seashore, a wonderful project would be to create a seashore seasonal wheel using papier-mâché creatures to depict seashore critters and arranged on a wooden circle, possibly a cross-section of a tree. Older students might create an ocean seasonal wheel illustrating the life cycles of marine creatures from birth to adulthood.

Other seasonal wheels could be made for the seasonal changes in a pond, lake, bog or forest. Young children might make a simple seasonal wheel illustrating the life cycle of a frog, a butterfly, a salmon or the seasonal cycle of an oak tree or maple. The possibilities seem endless.

Cross-cultural and Multicultural Seasonal Wheels

A seasonal wheel often reflects your worldview, what you find important, and what touches your heart. Although this article was created from a Kwakwaka‘wakw worldview, all peoples from all walks of life can participate in the making of a seasonal wheel, whether it is created in a group or individually. If you have a mix of students whose ancestry is from different cultures, you might want to have the students create a seasonal wheel that represents customs from other cultures. Such activities enable all students to feel accepted and know that their histories, culture and customs are accepted and appreciated.

Sources of Information

Here is a list of knowledgeable persons and resources that could be of assistance with the creation of your seasonal wheel:

- Elders and knowledge keepers,

- museums, historical archives, libraries,

- tribal, local government office, language and culture teachers,

- local high school biology, environmental education teachers,

- artists, musicians, and drama teachers who can be helpful in designing the final product, and

- local field guides to trees, shrubs, flowers, birds, and forest animals.

A Seasonal Wheel Never Goes Out of Date

A seasonal wheel can be carried over for a number of years or for a much shorter period of time. The finished product never goes out of date and can always be updated in successive years. A seasonal wheel can show the communities’ seasonal activities 500 years ago, 100 years ago, 50 years ago, today, and how the seasons are changing. In the past, people knew that the seasonal changes didn’t change much from year to year. They knew when to walk the stream beds, what plants would be in bloom, and what animals would be migrating through. In our modern world, change is accelerated and it could be important to discuss how climate change, resource depletion, and changes in ice conditions are significant changes affecting all of us. You might have two or three wheels that you can place one on top of another using clear overlay to see if the past and present are different or if it remains the same. For this type of comparison each layer might be a different colour. Printing them out separately would work too.

La men gwal gwagwixs’ala laxux (I am finished sharing about this).

REFERENCES

Boas, F. (1930). The Religion of the Kwakiutl Indians. New York: Columbia University Press.

Boas, F. (1921). Ethnology of the Kwakiutl. Based on data collected by George Hunt. In Bureau of American Ethnology, Thirty-fifth annual report of the Bureau of American Ethnology to the Secretary of the Smithsonian Institution, 1913-1914: Part 1 (pp. 43-794). Washington, DC: Bureau of American Ethnology. Retrieved from https://archive.org/details/thirtyfifthannua1914smit

Bureau of American Ethnology, Thirty-fifth annual report of the Bureau of American Ethnology to the Secretary of the Smithsonian Institution, 1913-1914: Part 1 (pp. 43-794). Washington, DC: Bureau of American Ethnology. Retrieved from https://archive.org/details/thirtyfifthannua1914smit

Kwakiutl District Council Land Resource Management Plan, Kwakwaka’wakw Elders Gatherings 1975–1999 (1999). Alert Bay, BC: Kwakiutl District Council.

Turner, N. J. (2005). The earth’s blanket: Traditional teachings for sustainable living. Vancouver, BC: Douglas & McIntyre.

Turner, N. C., & Bell, M.A.M. (1973). The ethnobotany of the southern Kwakiutl Indians of British Columbia, Economic Botany, 27(3), 257-310. Retrieved from http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/bf02907532