4

These are difficult stories. We bear witness in this chapter to the role of sport in furthering the settler colonial projects throughout Turtle Island. Here are some supports to access in the community and from a distance:

First Peoples House of Learning Cultural Support & Counselling

Niijkiwendidaa Anishnaabekwag Services Circle (Counselling & Healing Services for Indigenous Women & their Families) – 1-800-663-2696

Nogojiwanong Friendship Centre (705) 775-0387

Peterborough Community Counselling Resource Centre: (705) 742-4258

Hope for Wellness – Indigenous help line (online chat also available) – 1-855-242-3310

LGBT Youthline: askus@youthline.ca or text (647)694-4275

National Indian Residential School Crisis Line – 1-866-925-4419

Talk4Healing (a culturally-grounded helpline for Indigenous women):1-855-5544-HEAL

Section One: History

A) The Residential School System

Exercise 1: Notebook Prompt

We are asked to honour these stories with open hearts and open minds.

Which part of the chapter stood out to you? What were your feelings as you read it? (50 words)

| The part of the chapter that stood out to me the most was the way sports were used as a tool for assimilation rather than as a source of recreation for Indigenous children. The chapter explained how Indigenous traditions were repressed and replaced with Euro-Canadian sports to impose colonial values. It was hard to read how physical activity, otherwise seen as a positive, was turned against Indigenous identity, perpetuating systemic oppression rather than building real inclusion or empowerment. |

B) Keywords

Exercise 2: Notebook Prompt

Briefly define (point form is fine) one of the keywords in the padlet (may be one that you added yourself).

Settler Colonialism

|

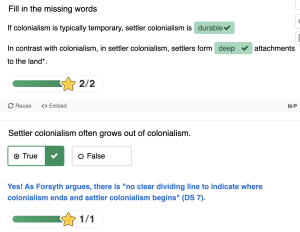

C) Settler Colonialism

Exercise 3: Complete the Activities

Exercise 4: Notebook Prompt

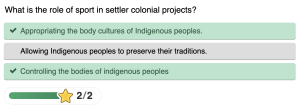

Although we have discussed in this module how the colonial project sought to suppress Indigenous cultures, it is important to note that it also appropriates and adapts Indigenous cultures and “body movement practices” (75) as part of a larger endeavour to “make settlers Indigenous” (75).

What does this look like? (write 2 or 3 sentences)

| This appropriation takes place when the settlers take Indigenous cultural practices such as traditional physical exercises, sports, and games and appropriate them, removing from them their former spiritual or cultural meanings. A case in point is lacrosse, which was a sacred game of the Indigenous and held immense spiritual meaning, and has been recreated as a competitive sporting event that exists in Euro-Canadian values. This process allows settlers to claim a connection to Indigenous identity and land but to still be in the role of marginalizing Indigenous peoples and taking away their sovereignty. |

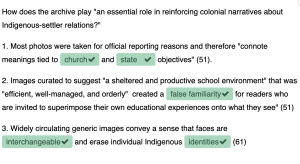

D) The Colonial Archive

Exercise 5: Complete the Activities

Section Two: Reconciliation

A) Reconciliation?

Exercise 6: Activity and Notebook Prompt

Visit the story called “The Skate” for an in-depth exploration of sport in the residential school system. At the bottom of the page you will see four questions to which you may respond by tweet, facebook message, or email:

How much freedom did you have to play as a child?

What values do we learn from different sports and games?

When residential staff took photos, what impression did they try to create?

Answer one of these questions (drawing on what you have learned in section one of this module or prior reading) and record it in your Notebook.

| When residential staff took photos, what impression did they try to create?

Residential school staff used pictures to create the illusion of normalcy and care, showing students engaging in sports and activities to suggest a healthy and enriching environment. Those pictures hid the true stories of abuse, cultural oppression, and involuntary assimilation, perpetuating colonial myth-making that justified the residential school system. |

B) Redefining Sport

B) Sport as Medicine

Exercise 7: Notebook Prompt

Make note of the many ways sport is considered medicine by the people interviewed in this video.

| Healing and Resilience – Sport helps Indigenous people recover from intergenerational trauma caused by colonialism, including the legacy of residential schools.

Cultural Connection – Physical activity and Indigenous games reclaim cultural pride and identity, reconnecting us to our spiritual and ancestral foundations. Mental and Emotional Well-being – Sport offers an outlet for grief, trauma, and stress, and improves mental health and self-esteem. Community and Belonging – Sport gives them a sense of community, mentorship, and common purpose. Physical Health – Sports encourage active lifestyles, and reduce health inequalities that typically affect Indigenous people disproportionately. Self-Determination—Indigenous-led sports programs allow communities to re-claim physical activity on terms meaningful to their values and traditions. The main sport talked about in this video was lacrosse, but it also showed how different sports connect the indigenous community. It was cool to see how thankful the new generations were for the sports that were passed down through generations and how much appreciation they had for those who had to go through the residential school system and how sports were a major concept that got them through those hard times. |

C) Sport For development

Exercise 7: Notebook Prompt

What does Waneek Horn-Miller mean when she says that the government is “trying but still approaching Indigenous sport development in a very colonial way”?

| Waneek Horn-Miller means that while the government is making efforts to support Indigenous sport development, but they are still doing so with a colonial approach. This means that programs and policies are created without fully adopting Indigenous voices, self-determination, or customary cultural practices. Instead of fully allowing Indigenous peoples to express their own sports and physical activity, the government brings in a Eurocentric system that prioritizes mainstream competitive sport over traditional Indigenous games and overall health. This maintains colonialist power relations in everyday life and limits true reconciliation. |

Exercise 8: Padlet Prompt

Add an image or brief comment reflecting some of “binding cultural symbols that constitute Canadian hockey discourse in Canada.” Record your responses in your Notebook as well.

| One of the most significant binding cultural symbols of Canadian hockey culture is the Maple Leaf, a national unifying, prideful, and identity symbol. It’s worn on the uniforms of many teams in the country, including Team Canada, and helps to bond and keep hockey as a unifying national sport. But this symbolization oftentimes marginalizes Indigenous histories and worldviews, framing hockey instead as a settler-colonial heritage rather than accepting its complex background with Indigenous peoples. |

Section Three: Decolonization

Part A: Reflection

Decolonization of sport refers to breaking down the colonial systems that historically excluded Indigenous athletes and removed Indigenous culture, with indigenization seeking the reintroduction of Indigenous self-governance, leadership, and knowledges within sporting contexts. Sports have previously been used as an assimilatory tool on Indigenous peoples that removed their ways of knowing and being to instill and replace it with Western values of exclusivity and ranking (Forsyth & O’Bonsawin, 2023). Today, decolonization in sport requires dismantling these structures, while indigenization prioritizes Indigenous knowledge and traditions within sport.

Individual and community reactions to TRC Calls to Action

The Truth and Reconciliation Commission Calls to Action 87-91 identify sport’s contribution to reconciliation in terms of Indigenous representation, accessibility, and cultural safety. While systemic change is being addressed through government policy, community and individual actions are also required, especially from settlers.

Supporting Indigenous-led sports programs is very important. The North American Indigenous Games (NAIG) and Indigenous youth leagues are opposed to the historical removal of Indigenous sporting heritage and are an arena in which Indigenous youth can regain their sports identity (Forsyth & O’Bonsawin, 2023). Western sports like hockey and soccer were imposed on Indigenous youth through residential schooling and banned Indigenous sports like lacrosse (Cooky & Antunovic, 2020). Programs like NAIG and initiatives by the Aboriginal Sport Circle address this historical exclusion.

Creating culturally safe and inclusive spaces is essential to reconciliation. Underfunding, racial bias and limited leadership opportunities are systemic obstacles that are frequently experienced by Indigenous athletes (Razack & Joseph, 2021). Anti-racism policy, cultural competency education and equitable funding to Indigenous athletes and coaches are what sports organizations require (Galily, 2019). Sport is Medicine examines sport’s healing and community-building potential among Indigenous peoples and documents a need for a place where Indigenous athletes are treated with respect (YouTube, 2023).

Reclaiming traditional sports ensures that Indigenous communities maintain control over their athletic traditions. Lacrosse was not only a competitive game but also a spiritual and diplomatic tradition to many Indigenous nations. The sport was used for conflict resolution, ceremony, and community solidarity before being overtaken by colonial powers as a commercialized, European-based sport (Forsyth & O’Bonsawin, 2023). Snowshoe racing and canoe racing were also essential to culture in history before they were taken and marginalized. These sports should be included in curricula at school and by sporting organizations to protect their historical significance (TRC, 2015).

Impact of Colonialism on Indigenous Sporting Culture

Colonial policies actively repressed Indigenous sport cultures as a tool of forced assimilation. Sport culture was made a criminal offense under the Indian Act, and by consequence, traditional games declined (Forsyth & O’Bonsawin, 2023). Western values in sport and European-style sports replaced Indigenous physical activities in residential schools (Cooky & Antunovic, 2020). This is just one of the reasons that Indigenous sport players are underrepresented in professional sports.

Integration of Indigenous Worldview

Restoring Indigenous perspectives in sport is essential for decolonization. Indigenous activities such as snowshoe racing and canoe racing were a spiritual, identity, and survival issue in their culture (Forsyth & O’Bonsawin, 2023). Indigenous-led initiatives that reintroduce these activities help to restore community pride. The video Sport is Medicine illustrates sport and Indigenous wellness and shows sport as a demonstration of reclamation and as a process of healing and resisting (YouTube, 2023).

By engaging with Indigenous-led programs, supporting and advocating for equitable policies, and merging Indigenous ideas into athletic spaces, sport can transition from a colonial tool to a place of empowerment and cultural restoration.

Part B:

Part C: Analysis

History Component

The historical reference points chosen for the Game Map emphasize how colonialism and sport were interconnected. Sport as a form of assimilation has been used by residential schools, which banned Indigenous games and imposed Western values on students (Forsyth & O’Bonsawin, 2023). The Indian Act has also marginalized Indigenous sport by criminalizing cultural expression and discouraging Indigenous sport tradition (TRC, 2015). The use of such historical sites highlights sport as a force used against Indigenous identity. A prime example of this is lacrosse. Lacrosse used to be a spiritual sport that had been commodified and colonized by colonizers who removed its cultural significance (Forsyth & O’Bonsawin, 2023). Another example of this can be seen through Tom Longboat, an Onondaga distance runner who battled institutionalized racism to become a champion athlete (Razack & Joseph, 2021). Longboat’s experiences are evidence of Indigenous athletes’ resilience and ongoing challenges.

These historical insights reinforce the importance of reclaiming Indigenous sporting traditions and addressing colonial injustices. By documenting this history, we are recognizing both the powerful impacts of settler colonialism and the importance of decolonization.

Reconciliation Component

The reconciliation points chosen in the Game Map reflect responses to TRC Calls to Action 87-91, emphasizing Indigenous inclusion and equity in sport. NAIG and comparable events celebrate Indigenous identity and sportsmanship and reverse colonial policies (Forsyth & O’Bonsawin, 2023). Another critical initiative is the Aboriginal Sport Circle which provides resources and leadership development for Indigenous athletes and coaches (Cooky & Antunovic, 2020).

The Indigenous-led coach development programs will address representation at leadership positions. Indigenous peoples have historically been left out of decision-making positions in sport organizations (TRC, 2015). Building Indigenous leadership will bring about cultural safety and allow Indigenous peoples to have a voice in policy that affects their lives.

Land acknowledgments and cultural competency in sport organizations are also part of the journey toward reconciliation (Galily, 2019). The Sport is Medicine video reiterates that sport should be a tool that heals and empowers and not one that excludes (YouTube, 2023). Although advances are being realized, systemic barriers must be removed to realize Indigenous sovereignty in sport.

Futures Component

The future of decolonizing sport depends on prioritizing Indigenous leadership and policy-making. One of the key actions is increasing Indigenous voice within sport organizations so that Indigenous peoples have a say in decision-making (Forsyth & O’Bonsawin, 2023). Increasing Indigenous-led leagues and programs will promote self-determination and self-governance in sport (NAIG, 2023).

Sport and coach programs that integrate Indigenous knowledge into competition frameworks, coaching, and sports are critical (Cooky & Antunovic, 2020). With these programs, Indigenous values and land-based movements and activities become an important aspect of sports culture.

Economic accessibility is a major issue as well. Indigenous peoples most often have issues with financing their sport engagement. Increased scholarships and grants for Indigenous sport participants will create access to equity (Razack & Joseph, 2021). The Sport is Medicine video suggests removing economic barriers to make sports more accessible and inclusive for more Indigenous youth (YouTube, 2023).

By creating these futures, we can move beyond symbolic reconciliation to structural change where sport is seen as a space for Indigenous cultural restoration, empowerment, and self-determination.

References

Cooky, C., & Antunovic, D. (2020). “This Isn’t Just About Us”: Articulations of Feminism in Media Narratives of Athlete Activism. Communication and Sport, 8(4-5), 692-711.

Forsyth, J., & O’Bonsawin, C. (2023). Decolonizing Sport. Halifax: Fernwood Publishing.

Galily, Y. (2019). “Shut up and dribble!”? Athletes’ activism in the age of twittersphere: The case of LeBron James. Technology in Society, 58, 101109.

Razack, S., & Joseph, J. (2021). Misogynoir in women’s sport media: Race, nation, and diaspora in the representation of Naomi Osaka. Media, Culture & Society, 43(2), 291-308.

Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada. (2015). Final Report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada, Volume One: Summary. McGill-Queen’s University Press.

CBC. (2023). Sport is Medicine: The importance of sport for Canada’s Indigenous peoples. [Video]. YouTube. https://youtu.be/UPAS82U8uwE

ESPN. (2023). The human experience behind being a transgender athlete | Outside the Lines. [Video]. YouTube. https://youtu.be/vjEmbpO27o4