8 Visual Culture and The Environment

J. Keri Cronin and Hannah Dobbie

Environmental concerns dominate the headlines these days, with events like floods, extreme temperatures, and wildfires causing irreparable damage to our homes, health, communities, and ecosystems. For example, during the summer of 2023 Canada experienced a record number of wildfires with impacts spreading across North America.

When climate disasters hit, visual culture can play an important role in providing up-to-date information. From data visualisation and maps to nature documentaries and pictures shared on social media pages, imagery is an important part of a collective response to the climate crisis. News organisations allow us to see footage of hurricanes, floods, and wildfires, bringing a sense of urgency to the disasters even if we live far away from where they are taking place.

Citizen journalism is another important source of information allowing for a range of voices and perspectives to become part of the larger story. Many turn to online sharing sites like YouTube for current events coverage, although the ease with which false information can spread through these types of channels is another reason to be a vigilant, critical thinker when it comes to information the information presented, especially in emergency situations.

The role of the media in conveying information about the environment and the climate crisis is critical. The United Nations’s Intergovernmental Panel of Experts on Climate Change notes the “huge responsibility” that journalists and the media companies they work for have when it comes to environmental issues. As Laura Quiñones has argued, media can help to “build public support to accelerate climate mitigation – the efforts to reduce or prevent the emission of the greenhouse gases that are heating our planet – but it can also be used to do exactly the opposite.”[1]

Images, videos, and other methods of visual communication shape our understanding of the world’s major events, including environmental issues. Unlike decades past, we have more visual exposure than ever to global crises. With this, there is opportunity for panic, fear, and hopelessness to become the dominant response. Mixed with a sense of desperate urgency for seemingly unattainable change, many of us are left unsure of what to do.

Although the steady stream of news and images about environmental issues can feel overwhelming, we must remember that we are not alone in the fight for a better future, and with collective action we can inspire change. Visual culture as a source of information is a powerful tool in efforts by climate and environmental activists, and their work can create a lasting impact on a broad audience through a wide range of channels. But it is also important to remember that visual culture also includes creative expression and ways to imagine different futures. For this reason, we will explore both visual culture through an eco-critical lens as well as eco-activist art in this chapter.

Representing the World We See

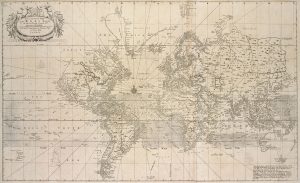

Images have long shaped the way people have made sense of the world around them. Landscape paintings and maps, for example, have been important forms of visual representations for centuries. These are, for the most part, two dimensional representations of the complex, messy, three dimensional world. Artists and cartographers have to make decisions about what to include in their work. As such, these representations of place have implications beyond the frame because they can reinforce certain world views and perspectives. For example, maps were essential tools of colonialism, and different approaches to map making can shape the information they provide in different ways.

Image Source: New York Public Library, Public Domain

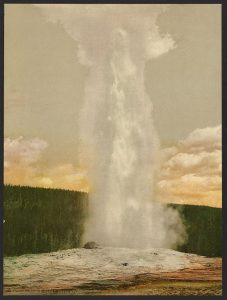

While many images in the Western landscape tradition can appear peaceful, serene, and aesthetically-pleasing, they often require a closer look. There is often more to the story when we see images of seemingly “pristine nature.” The history of National Parks, for example, is often a history of the removal and erasure of Indigenous peoples. Further, many of Canada’s National Parks were built using forced labour.

Image Source: Library of Congress, Public Domain

In other instances, a landscape picture may include tiny figures somewhere within the composition, frequently representations of Indigenous peoples or of rural workers. (Again, we are talking about the Western landscape tradition, the type of landscape picture that dominated places like Europe and North America for centuries.)

Image Source: Art Institute of Chicago, Public Domain

By making Indigenous people and rural workers blend in as part of the landscape, the artist is participating in a much broader visual tradition of aestheticizing these groups of people, offering simplistic, often stereotypical representations that are unconnected with the realities faced by Indigenous peoples and the working class in the very spaces being depicted.

Landscape paintings like the ones above by Thomas Cole, John Rathborne, and George Morland require careful visual and contextual analysis. In other words, we need to go back to some of the questions and frameworks we looked at earlier in this book. What choices has the artist made? Why does the picture look the way it does?

In recent years this type of visual culture has been examined through different critical lenses. For example, curatorial staff at the Art Institute of Chicago have noted that with Cole’s painting of Niagara Falls, he chose to leave out “the factories, scenic overlooks, and hotels that populated the area in the early 19th century” and that he “erased the human devastation wrought by colonialism and conquest in the region, which encompassed Attiwonderonk, Haudenosaunee, and Wenrohronon lands.”[2] Likewise, important conversations about how popular and beloved landscape paintings like those by The Group of Seven have erased Indigenous histories are happening while, at the same time, organisations like the Indigenous Mapping Collective are pushing back against a long history of colonial map-making. How do the stories we tell ourselves about a place change when these additional perspectives are taken into account?

Visual Culture in the Anthropocene

The term Anthropocene is often used to describe the current time we are living in, a time where human activities are altering the planet in unprecedented ways. The concept of the Anthropocene relates to visual culture on many levels–from finding creative ways to represent changes in the environment to wasteful practices in the art world and the toxic materials used in the production of some forms of visual culture. The Anthropocene Project, a multi-disciplinary body of work created by Nicholas de Pencier, Edward Burtynsky and Jennifer Baichwal uses a range of imagery to reflect on the impact we, as humans, have had on our planet.

Reflection Exercise

Scroll through this BBC image story about landscapes scarred by human interference. Choose the image that you feel most impacted by, and spend 10-15 minutes doing some freewriting on the image you selected.

You can write about any aspect of these images, but if you feel stuck here are some questions to get you started:

- What does this image make you feel, and why?

- How does this image connect to the concept of the Anthropocene?

- Do you think these images would be effective as part of environmental activist efforts?

- Is there a sense of aesthetic beauty to these images?

- Is there something missing in these images?

Practice Activity: Eco-Activist Art

In this section, we will look at three examples of eco-activist artwork. For each example below, do the following:

- Click the link to explore the artworks and learn more about the artist

- Conduct a brief, informal visual analysis of one of the artworks (this is an exercise, so there are no strict rules – if it is helpful, try to aim for half a page of notes about the work; bullet points are okay!)

- Use freewriting to come up with a few sentences reflecting on the artwork. Think about your personal reaction, what the piece means to you, and the context this work was created in.

- Ceramic underwater sculptures by artist Vanessa Albury, designed to revive filter-feeder populations.

- Paintings by Lisa Ericson of animals half-submerged in water as an environmental warning.

- Work by Rashid Rana and Amin Rehman addressing Pakistan’s devastating floods.

Before moving on, take a look at this article about the role of art in conveying information about the climate crisis. Take a minute to write down your thoughts on this idea of art as a means of communication.

Greenwashing

Many corporations, brands, and institutions use buzzwords and symbols to make us believe they are supporting the climate justice cause, when in fact, they are continuing to profit off of detrimental practices and unsustainable methods. This practice is called greenwashing and it is important to be an informed consumer if you are concerned about making consumer choices that have a smaller environmental footprint. Advertising can be misleading! Even one of the most iconic pieces of visual culture from the environmental movement–the recycle arrows–can sometimes cause misinformation.

Staying Positive Amidst Eco-Anxiety

This chapter has covered some heavy content that can quickly become overwhelming and anxiety-inducing. If you feel this way, you are not alone! Take a look at Gen Dread, a book and blog dedicated to finding purpose amidst the climate crisis. You can also keep an eye out for positive news stories. Sites like The Daily Climate and Happy Eco News are great resources to turn to when you need a heart-warming environmental pick-me-up.

Stay attuned to announcements from institutions and organisations you support, as many places are striving to make a difference–for example, the Royal Ontario Museum just hired what might be the world’s first Climate Change Curator! A number of arts organisations are finding ways to bring more sustainable materials and practices to the art world including the Gallery Climate Coalition, the Land Art Agency and The Sustainable Darkroom.

When feeling lost, try to focus on the things you can control and the changes you can make in your own life. These small steps will make a difference, but remember that major corporations and industries are the leading contributors to climate change. Talk with your friends and family, join a club or activist group in your community, or get online and find organisations you can support in the fight for climate justice. Our governments, institutions, and corporations need to be held accountable, so find your place in the community and use your skills to make a change. We are stronger when we take collective action, so make connections and share your voice!

- Laura Quiñones, “Five Ways Media and Journalists Can Support Climate Action While Tackling Misinformation,” UN News (3 October 2022): https://news.un.org/en/story/2022/10/1129162 ↵

- Distant View of Niagara Falls, Art Institute of Chicago https://www.artic.edu/artworks/90048/distant-view-of-niagara-falls ↵