2 Visual and Contextual Analysis

J. Keri Cronin and Hannah Dobbie

The study of visual culture relies on two key skill sets: visual analysis and contextual analysis.

Visual Analysis

Visual Analysis is just a fancy way of saying “give a detailed description of the image.” It is easy to assume that visual analysis is easy or that it isn’t necessary because anyone can just look at the image and see the same thing you see. But is it really that simple?

As individual viewers we all bring our own background, perspective, education, and ideas to the viewing of an image. What you notice right away in an image may not be the same thing your classmate (or your grandmother or your neighbour) notices. And this is perfectly fine!

What do you see when you look at the images below?

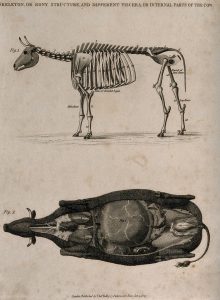

In all three cases we have pictures of cows, but there are some important similarities and differences. What do you think is important to note about these images?

Image Source: Wellcome Collection (Public Domain)

Reflection Exercise

Take a 5-10 minutes to jot down a detailed description (visual analysis) for each of the images above.

- What do you notice?

- What do you see?

- What part of the image is your eye drawn to first?

- How are these images similar? How are they different?

Contextual Analysis

Contextual analysis is another very important skill for studying images. This is a fancy way of saying “we need more information about this picture.” You will often have to do external research to build and support your contextual analysis. There is an old saying that “a picture is worth a thousand words,” but we need to think carefully and critically about this. A picture can not tell us everything we might want to know about it! Sometimes it is very important to dig deeper through research to learn more about an image in order to understand how it participates in the meaning making process.

Here is a list of some questions that are useful for guiding contextual analysis. This is not an exhaustive list and not all questions will apply in all cases:

- Who made this image? Why?

- Where was the image made? (In a different part of the world? In a laboratory? On the beach?)

- Who was the intended audience for this image?

- Where was the image meant to be viewed? (A textbook? A gallery? As part of a movie set? In a family photo album?)

- When was this image made? How do you know?

- What kinds of technologies were used to make this image? What kinds of limitations were there on this technology at this time?

- Is there text in the image? If so, how does it shape our understanding of what we are looking at? What about the image caption? How does it shape our understanding of what we are looking at?

Sometimes you can get clues from the image that can help you answer these kinds of questions, but often you will have to branch out and turn to books, articles, websites, documentary films, and other resources to help build and develop your contextual analysis.

In our examples above the captions give us quite a bit of information. We learn, for instance, who made the pictures (and, in one case, we learn that this information isn’t known). We learn when the images were made and the type of pictures they are–although we may need to look up what an etching, stereograph, or an albumen print is. The titles are fairly descriptive in that they provide us some basic information about what we are looking at.

Reflection Exercise – Part II

The visual analysis we just did combined with the information provided in the image captions gives us a place to start with our investigation into these images. But are many things that we still don’t know about these pictures.

What other things might we want to know if we were going to write about these pictures? Take a few moments and jot down a list of questions you have about these images.

As we generate questions based on these images and then start to do the research to find out the answers to those questions we are starting to build our contextual analysis. Through research we would learn, for instance, that the firm of Underwood & Underwood was a leading manufacturer of stereograph cards in the 19th century and that stereograph cards had a massive public and commercial appeal. The two images, when viewed through a special device known as a stereoscope, merge together to form an image that looks 3-D. Imagine how exciting this would be for viewers in an age before television, movies, and video games. Some have even described this as an early form of virtual reality!

Further research will show us that Edward H. Hacker was a printmaker in Britain in the 19th century and that he was best known for creating engravings of animal pictures. In an era when it wasn’t easy to reproduce paintings, this allowed multiple copies of an image to be shared and circulated. In our example, above he is reproducing a painting by William Henry Davis, an artist who specialised in portraits of livestock.

Today it might seem odd to us that people would want pictures painted of their cows and we might even wonder why someone would hire a printmaker to make reproductions of these images. Why would people want images of their cows? And further, why does the cow in the first picture above look so strange? She is so enormous that her little tiny, skinny legs couldn’t possibly support her body. What is going on here? Did Davis now know how to paint cows?

In fact, Davis was a well-respected artist. The answer to this question can be discovered through a bit of research (more contextual analysis). As we dig into this investigation, we would soon learn that this type of picture was part of a larger 19th trend for creating images of livestock that exaggerated their features as a way to advertise certain breeds and breeders. In other words, the farmers that were commissioning these images were using these pictures to try and prove that their animals were better than the animals owned by competing farmers. These pictures can not be separated out from the economics of 18th and 19th century British farming practices.

In 2018 the Museum of English Rural Life posted a photograph of a very large ram with the words “look at this absolute unit.” This Twitter post went viral and brought a lot of attention to the history behind these kinds of images. Having a picture like this circulate on social media brought a new layer of meaning to the photograph. It didn’t replace the original context, but it added to the discussions about it.

When an image is taken out of its original context new meanings can be generated. Take, for example, a controversial advertising campaign launched in the spring of 2023 by the Italian government. It features the very recognizable central figure from Sandro Botticelli’s 15th century painting known as “ Birth of Venus.” But in this campaign she is out and about enjoying the tourist sites in Italy, playing the role of Instagram influencer. This campaign provoked a strong reaction and many people criticised what they saw as trivialising and making a mockery of a beloved work of art. The associations people have with this painting–that it is a “masterpiece” to be admired and venerated–have fueled this criticism. If the central figure in these advertisements was not a recognizable figure it is unlikely that there would have been any controversy at all. By taking this figure out of context and putting her in AI generated scenes of Italian tourism, some feel it changes the meaning of the original picture. Love it or hate it, the one thing everyone agrees on is that this campaign has generated much discussion!

Visual and Contextual Analysis Exercise

Find a picture that you think expresses something about who you are. It can be from your childhood, a photograph of your dorm room, or a picture of the aunt who taught you how to read. Perhaps it is a picture of you cheering on your favourite sports team or of a special dinner shared with close friends. It doesn’t matter what the subject is as long as it is an example of a picture that you think says something about you.

Step 1 (Visual Analysis): Write a description of this picture. Try to stick to only description in this step, really look at the picture carefully and consider things like:

- What medium is it (e.g.: is it a photograph, a painting, etc.)?

- What colours are used?

- How is it composed? How big is it?

- Are there people in the image?

- Is the image dark or light?

- What is in the background?

- Is there anything blurry or unclear?

*Note: This is not an exhaustive list of questions. Rather, they are given as examples to help you think about what kinds of things to focus on.

Step 2 (Contextual Analysis): Imagine you are going to show this picture to a complete stranger, someone who doesn’t know you at all. Make a list of everything you think that person needs to know about the picture in order to learn a bit about you? What information might help that person understand why this picture is meaningful for you? For example, was this photograph taken on your birthday? Is it a picture of your first pet? Is the person who is blurry in the background your best friend who moved away when you were 11? Then think about why these things are important to you. In other words, what do you know about this picture that wouldn’t be obvious to someone else?

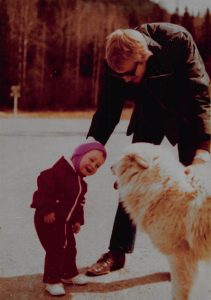

If I were doing this exercise with this photograph, in step #1 I would focus on things like the colour of the child’s clothing, the size of the dog, and the way the adult, child, and dog are posed, including that the man has one hand on the child, one hand on the dog. I would talk about it being a photograph and how the faded tones suggest that this is an old photograph. I would note that the photograph was taken outside and that these three are standing on what appears to be pavement but that there are trees in the background. There is also what appears to be a wooden sign in the background but it is too blurry to read. I would also point out that the shadows on the ground indicate that it was a sunny day, but the type of clothing the two human figures are wearing suggests that it was also a cold day.

If I were to continue on and complete step #2 I would list that this was a photograph taken in the mid-1970s by my mother and that it is a picture of me (Keri) and my uncle with a dog we happened to meet in the parking lot of Mount Robson Park while our family was moving from British Columbia to Alberta. This was not our dog. We had never met him before nor did we ever see him again. But he was friendly, and I was absolutely enthralled by how fluffy he was. My uncle took me over to introduce me to the dog, staying close to make sure the dog didn’t hurt me.

This picture holds meaning for me for a number of reasons. First of all, it is an early example of my love of animals. Secondly, Mount Robson Park is part of the Canadian Rocky Mountains and was often a destination for family vacations. These trips shaped my interest in nature and outdoor activities in spaces like Provincial and National Parks. This led to me deciding to write my PhD thesis on the visual culture of these kinds of places, a document that was eventually turned into a book. And lastly, this picture has taken on a new layer of importance for me lately as my uncle pictured here recently died of cancer. Even though it isn’t a great picture in terms of technical quality, it is a picture that I have framed in my house because it holds a lot of meaning for me.

By doing this exercise you are slowing down the process of meaning making and thinking about how the visual elements of the image relate to the larger context that helps to shape why this picture holds meaning for you. You can see how the two types of analysis–visual and contextual–work together. You need both halves of this equation. By slowing down and doing some deep noticing in our visual analysis, we can notice things that become significant when we switch over to contextual analysis. And our contextual analysis can provide us a starting place for further research if needed.

With this exercise you were working with an image that you are already very familiar with. But this same process can get repeated with any image. When you are working with an image that isn’t from your own personal life, there will likely be more steps needed to arrive at a contextual analysis–research, further reading, etc.–but the process itself remains the foundation for critical thinking about images.