5 Representing Ourselves, Representing Others

J. Keri Cronin and Hannah Dobbie

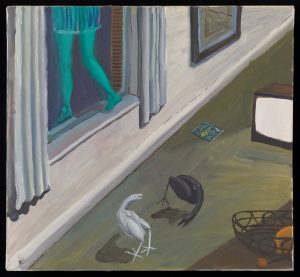

Image Source: Smithsonian American Art Museum and its Renwick Gallery (CC0)

Visual culture plays a big part in the stories we tell about ourselves. From the posters and framed photographs we have in our homes, to the stickers we put on our laptops or the logos on our clothing, images are a part of our personal identity. We choose to surround ourselves with certain kinds of images because they make us feel good or because they remind us of things that are important to us. These images also reveal a bit about our personality to other people.

What To Wear?

Even our choice of clothing presents an outward statement about who we are to the world. Our ideas about what is acceptable to wear, what is fashionable, what is out of style, and what is inappropriate to wear are shaped, in large part, through broader cultural and social ideas that are often reinforced through visual culture. These things shift and change over time and in different parts of the world.

Further, it is important to understand that the visual culture of fashion and fashion history has always been deeply entangled with broader cultural ideas about gender, race, culture, sexuality, and notions of ideal beauty.

Image Source: New York Public Library, Public Domain

Reflection Exercise

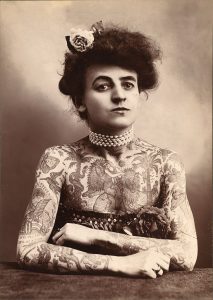

Think about the types of visual culture that you use to express who you are. From the items you display in your home to tattoos and jewellery you adorn yourself with, your choices say something about you.

Select three of these items and focus on them in a 10 minute freewriting session. If you don’t know what to write, the following prompts can get you started:

- What do they look like?

- What type of images/objects are they?

- Where did you get them from?

- How do they make you feel?

- What do you think they say about you to others?

Portraiture

Portraiture is a fascinating genre of visual culture. Many portraits from previous eras are paintings of the wealthy, elite, and, of course, royalty. It was expensive to have one’s portrait painted and the resulting images were a concrete demonstration of wealth, privilege, and status. As we can see in the example above by Paulus Moreelse, sitters (the fancy term used to describe the person who is in the portrait) were often depicted wearing luxurious clothing and jewellery, the finest fabrics and the latest styles of the day. Even though the identity of the “young lady” in the Moreelse painting is not given here, we can discern information about her status by the fact that she had her portrait painted. This was not something that everyone in 17th century Europe could easily afford.

These last three examples of portraits are all of named individuals: Mrs. Grace Dalrymple Elliott, Thodore Duret, and Queen Charlotte. (Yes, the Queen Charlotte who is portrayed in Queen Charlotte: A Bridgerton Story–another layer of visual culture!)

These portraits are also painted by well-known and celebrated artists who are themselves the focus of art historical research, museum exhibitions, and biographies. This can shift the meaning of the painting depending upon the context in which it was viewed. So, for example, research by curators at the Metropolitan Museum of Art has lead to the speculation that the portrait of Mrs. Grace Dalrymple Elliott was commissioned by George Cholmondeley, the first marquis of Cholmondeley and a man reported to be Mrs. Elliott’s lover. In that context, the portrait had a very specific meaning. However, when it is exhibited in an art gallery today it is often shown as an example of “a Gainsborough” which layers on a different set of meanings. As we learned earlier in this book, the meaning of a picture can shift and change depending upon the context in which it is viewed.

Perhaps not surprisingly, one of the early applications of photography was portraiture. With processes like the daguerreotype it became feasible for a larger portion of the population to sit for a portrait (or “likeness”). A visit to the photographer’s studio was an important event, and people often dressed in their best clothes for the occasion. Mobile studios run by itinerant photographers offered even more opportunities for people to obtain portraits of themselves and their loved ones.

Image Source: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Public Domain

Image Source: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Public Domain

(Coated salted paper print from glass negative, 1850s and 1860s)

Image Source: Metropolitan Museum of Art, Public Domain

Photographic portrait studios popped up in many towns and cities, including the city that Brock University is located in, St. Catharines Ontario.

The American Civil War (1861-1865) generated hundreds of photographs, including portraits of soldiers and family members waiting at home. The photograph below (a hand-coloured tintype) shows a young girl dressed in mourning clothes. She clutches a photographic portrait of her father who has been killed in the war. This image demonstrates the role of photography in mourning and remembrance, and is part of a large collection of photographs from this conflict.

Self-Portraits and Selfies

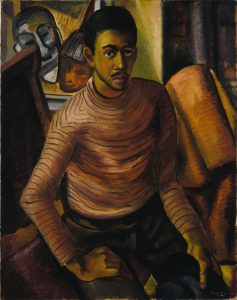

Image Source: Smithsonian American Art Museum and its Renwick Gallery (CC0)

As discussed above, the image we chose to present of ourselves to the world is, in many ways, shaped by visual culture. For artists, self-portraiture can play an important part of this self-fashioning as they allow a further opportunity for artists to decide how they wish to be seen. There are many reasons why an artist might decide to make a self-portrait. It can be a way of showcasing their skill and talent, a way to seek recognition as an artist. This has been particularly important for women artists throughout history as they often had to fight to be taken seriously in a profession dominated by men.

For centuries women were excluded from life drawing classes, classes that provided art students the opportunity to learn to realistically draw the human figure by working with a nude model. In the British Royal Academy, for example, a petition was circulated in 1878 through which female students argued for the right to “study from the figure.”[1] Without the opportunity to learn to draw the human form in life drawing classes, many women artists used the only model they had available–their own bodies.

Self-portraits continue to give many artists a sense of empowerment today. For example, Canadian artist Quinn Rockliff turned to self-portraiture as a way to heal after a sexual assault. Australian artist Katie Brebner Griffin has a disability and lives with chronic pain. In interviews about her art she talks about the constant cycle of medical appointments and tests, and how she started making self-portraits because she “wanted to find a different way to engage with my body that didn’t involve having to tolerate something happening to it.” [2]

Today selfies are a big part of social media. While photographic self-portraits have been part of photography since the early days of the medium, the term “selfie” in our present-day usage tends to be reserved for images taken with the intent of sharing them on social media. In 2013 the Oxford Dictionaries selected “selfie” as their “word of the year,” a testament to their popularity as a form of visual culture.

A 2018 study noted a dramatic increase in interest in plastic surgery, specifically people who were embarrassed about the way their nose looked. Further investigation revealed that this was due, in large part, to selfies. The close distance between the camera and a person’s face when making a typical selfie creates a sense of distortion in which a person’s nose can appear larger than it actually is. A typical distance between the face and camera in a selfie is 12 inches while a regular photographic portrait is often taken from a distance of about 5 feet away. This difference in distance has a dramatic effect on how a person appears in the resulting photograph.[3] Yet another reason to think critically about visual culture that surrounds us!

Reflection Exercise

Think about a self-portrait you have made (or a selfie you have taken). Spend 5-10 minutes free writing on it. If you don’t know what to write, the prompts below can help get you started.

- What prompted you to make it? (an assignment? A new haircut?)

- What did it look like? Be specific!

- What did you include in the frame? What did you crop/edit out?

- What was the process like? Did you have to use a mirror to paint it? Did you take dozens of photographs on your phone until you found one that you liked?

- Did you share it with anyone? If so, how did people respond to it? If not, why did you decide to keep it private?

The Gaze

The concept of “the gaze” is significant when we consider the topic “representing ourselves, representing others.” The gaze as a theoretical and philosophical framework has been discussed by a wide range of scholars, including Jean-Paul Sartre, Michel Foucault, Jacques Derrida, John Berger, and Laura Mulvey. Essentially it refers to the power dynamics inherent in the way we look at and represent others.

So, what does that mean in practical terms? Here is a list of questions that can get us thinking about the concept of “the gaze” in visual culture:

- Who is doing the looking? Who is being looked at? (note: this can apply to what is going on inside the frame of the image but it also can apply to the process of an external viewer looking at the picture)

- Who was the image made for and why?

- Does the person in the image have control over how they are presented? Do they have control over what happens to the image once it is made?

- How does the imagery reinforce the relationships that exist between those who made the images and those who appear in the images? Is the subject of the picture treated as the equal of the person making the picture? How does the image convey this information?

- Is there room for alternate interpretations?

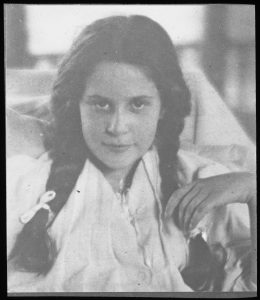

Image Source: Art Institute of Chicago, Public Domain

Alfred Stieglitz’s photograph of his daughter Katherine (Kitty) was taken when she was about ten years old. In this photograph she is clearly aware of being photographed by her father. She returns his gaze with what appears to be a bit of attitude. The relationship here is one between father and daughter–while they are not equals (Alfred the caregiving parent, Kitty the child) it is very likely Kitty had some agency and input in the process of making this photograph.

Likewise, in the image of Myrtle Lind above, she not only returns the photographer’s gaze but also “shoots back” with a camera of her own. Myrtle Lind was a film and theatre actor in the early 20th century and this could have been a promotional photograph. She is comfortable in front of the camera and is clearly aware her picture is being taken. Again, she would have been an active and willing participant in this photo shoot.

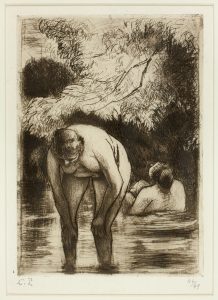

Compare this with Pissarro’s bathers below. These women do not appear to be aware that they are being looked at. They are engaged in the private act of bathing. They are unclothed and shown in a private space where they assumed they would not be observed. The dynamic of the gaze is very different here, even voyeuristic. The women in this picture appear to be unaware of being observed. While it is entirely possible that this scene was drawn from Pissarro’s imagination or that he had staged this scene with models, the resulting images convey the idea that the nude female body is meant to be objectified and gazed upon. This picture is part of a larger body of imagery that has reinforced this notion in Western culture over time.

This kind of representation is often referred to as “the male gaze,” which assumes an image like Pissarro’s print above was created for the pleasure and enjoyment of a cis, straight male viewer. This has been challenged in recent years as we see artists pushing back against the male gaze. For example, comedian Hannah Gadsby has taken on the trope of the passive female nude in art with her documentary series called “Nakedy Nudes.”

There has also been a rise in scholarship suggesting alternate readings of images from art history to include approaches that consider the queer gaze. It is important to note, however, that visual culture offering alternatives to the dominant cis, straight male gaze have long existed. Many of Alice Austen’s photographs, for example, show her life as a lesbian and part of the LGBTQ2S+ community in New York State during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Another example–and one that made headlines in the early 20th century–was Paul Cadmus’s painting called The Fleet’s In from 1934. It was considered so scandalous by the U.S. Navy that retired Navy General Admiral Hugh Rodman sent someone in to lift it right off the walls of the Corcoran Gallery. Today this painting is in high demand and is often on loan to galleries and museums, an excellent example of how the way an image is understood and valued can shift over time.

Tina M. Campt, a scholar at Princeton, has published several widely on the concept of the Black gaze, “a gaze that forces viewers to engage Blackness from a different and discomforting vantage point.” Through this framework there is both a sense of reclamation of the “uncomfortable Black visual archive” that has accumulated through generations of image making as well as a strong emphasis on “energizing and infusing Black popular culture in striking and unorthodox ways.”[4]

The Medical Gaze

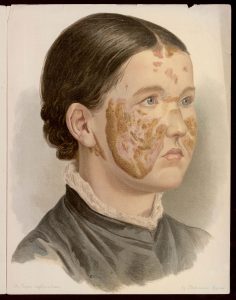

The “medical gaze” is a term used to describe the observations and representations of patients by doctors and other members of the medical profession.

Medical archives are full of images in which the conventions of portraiture have been adopted for the purposes of studying patients. While some of the information gleaned through these processes has undoubtedly been helpful in terms of finding cures and sharing information about various diseases, disabilities, and illnesses, from a patient perspective this can be a dehumanising process.

The colour image below was taken from a book called On lupus erythematosus; or Bat’s-Wing Disease published by Balmanno Squire in 1887. In that text he describes the medical history and treatment of the woman represented here, a 37 year old unnamed woman from Glasgow who was suffering from lupus erythematosus. According to his text, Squire was able to bring her some relief after years of suffering. In this context, the image included in the book portrays the woman as a patient, the subject of the medical gaze. She might very well have been pleased to get some help managing her disease. But this is not a portrait. The focus here is on her illness, and she would have had little control over how the image was made, used, or circulated.

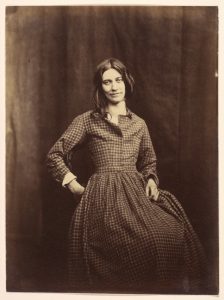

Hugh Welch Diamond was a 19th century doctor in who believed that photography was an important professional tool. Between the years 1848-1858, he photographed the patients of the Surrey County Asylum in England where he was a superintendent. He believed that a photograph could help him make connections between physical appearance and state of mind. This approach was influenced by a concept known as physiognomy, a now debunked “dubious science” that perpetuated harmful stereotypes about certain groups of people.[5]

Diamond’s belief in physiognomy was so strong that he was convinced that the photographs in his series image did not need further interpretation to be understood by a viewer, noting that “the picture speaks for itself.”[6] And yet as we consider this picture we are left with many questions. We can not glean information about this woman’s condition from the photograph, nor do we know her name or any other details about her. Again, this is an example of an image made in the context of the “medical gaze.” This woman did not have the freedom to represent herself in the way she might like–even her clothing is institutional, a uniform worn by other women in Diamond’s photographs.

While the theories that informed Diamond’s approach to photography are no longer seen as a valid or legitimate way of assessing patients, there is still much work to be done in terms of the representation and inclusion of people living with disabilities and illness in our world today.

Art and other creative practices can be an important outlet and form of expression for people living with illness and disability. For example, Bryan Charnley was a British artist who turned to art to help him deal with his struggles with schizophrenia. His work is now part of the Wellcome Collection.

Image Source: Wellcome Collection (CC BY-NC 4.0)

The art world is slowly becoming more inclusive of artists with disabilities and illnesses, although ableism still presents significant challenges and barriers for many. There are a number of organisations that foster opportunities for expression and representation beyond the limiting confines of the medical gaze. For example, Tangled Art + Disability in Toronto aims “to support disability-identified artists, to cultivate Disability Arts in Canada, and to enhance access to the arts for artists and all audiences,” and The Willow Art Community in St Catharines “fosters safe spaces for creative exploration and connections for people with living experience of mental illness or substance use in Niagara.”

Reflection Exercise

- Read Circe Henestrosa’s article for the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco called “Frida Kahlo’s Construction of Identity: Disability, Ethnicity, and Dress” from March 2020.

- How do some of the concepts from this chapter apply to Henestrosa’s analysis of Frida Kahlo’s life and art? Spend 10-15 minutes reflecting on these connections through a freewriting session.

- Amy Bluett, “Victorian women and the Fight for Arts Training, Royal Academy (March 2, 2021 https://www.royalacademy.org.uk/article/striving-after-excellence-victorian ↵

- Katie Brebner Griffin, “As a disabled woman, my self-portraits help me reclaim my body,” ABC Everyday/Australian Broadcasting Corporation https://www.abc.net.au/everyday/self-portraits-help-me-reclaim-my-body/102472960 ↵

- Brittany Ward, Max Ward, Ohad Fried, and Boris Paskhover, “Nasal Distortion in Short-Distance Photographs: The Selfie Effect,” JAMA Facial Plastic Surgery Vol. 20, no 4 (July/August 2018): 333-335. ↵

- [Tina M. Campt, “How Black Artists Are Shaping a Distinctly Black Gaze,” Hyperallergic (August 22, 2021): https://hyperallergic.com/671547/how-black-artists-are-shaping-a-distinctly-black-gaze-tina-m-campt/] ↵

- Sarah Waldorf, “Physiognomy, The Beautiful Pseudoscience,” The Getty Museum Blog (October 8, 2012): https://blogs.getty.edu/iris/physiognomy-the-beautiful-pseudoscience/ ↵

- Mary Warner Marien, Photography a Cultural History, London: Laurence King (2006), p37 ↵