7 The Visual Culture of Consumerism and Fashion

J. Keri Cronin and Hannah Dobbie

Image Source: New York Public Library, Public Domain

Advertising, Brand Culture, and Consumerism

Advertising is all around us. Everywhere we look, we are inundated with images and messages about things we should want, urging us to participate in the cycle of consumption. Companies and corporations want to make money, and to do so, they require that we, the consumers, purchase their goods and services. They lure us into their world through visual culture found in advertisements, social media posts, and corporate branding.

Companies and corporations spend a lot of time and money cultivating their brands, a visual identity that will appeal to their target demographic. In pushing a narrative through their advertising and marketing, brands suggest that if you buy their product, you will fit in, you will belong. They are selling a lifestyle, an idea, an often unattainable vision of what could be, which all goes beyond the product itself. Often this involves celebrity endorsements, but these can lead to mixed consumer response.

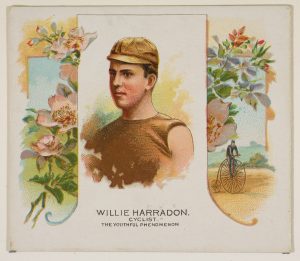

Celebrity endorsements are commonplace today, but they have a long history. The image below was published by a cigarette company (Allen & Ginter) and features the image of a cyclist named Willie Harradon who was making headlines with his performances in cycling races during the 1880s. Associating athletics and tobacco may seem odd to us today, especially given restrictions and bans on advertising tobacco products in several places, but the information we now have about links between health and smoking was not always known. Further, advertisements for tobacco products in the early 20th century often included endorsements from medical doctors! This example is a good reminder of how important contextual analysis is when we are looking at images–especially from previous eras. Assumptions and ideas we hold today may not have been commonplace in different places or time periods.

(Commercial lithograph published by Allen & Ginter Cigarettes, 1888)

Image Source: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, The Jefferson R. Burdick Collection, Public Domain

Sometimes advertising and branding will make reference to current events, shifting social norms, and political issues. When this happens, the reaction can be mixed. Some praise these campaigns for their attempt to make a positive difference in the world. Others may boycott the company if they don’t personally support the issue, topic, or angle referred to in the advertising campaign. Some may be cynical about these kinds of campaigns, uncomfortable with how an important social issue has been co-opted for selling a product. In other words, there are often questions about the sincerity of “brand activism.”

In recent years, a number of brands and logos that contained offensive aspects (for example, racist stereotypes), have been reexamined and rethought. Some companies have begun to change their advertising and branding practices in an attempt to be more inclusive. For example, Mountain Equipment Co-op (MEC) has made a commitment to including more racial diversity in their advertising.

Reflection Exercise

As you go about your day-to-day activities, keep an eye out for the advertisements you see. Select three to write about in this exercise. If possible, try to go beyond internet advertisements for at least one of your examples. You might find it helpful to snap a picture of the advertisement or take some notes or sketches of it so you can refer back to it.

Do a visual analysis of these advertisements and consider the following questions:

- What do they look like?

- What is included in the advertisement?

- What colours are used?

- What visual strategies or techniques are used to draw the viewer’s attention?

- Where did you see this ad?

- How does its placement help to generate meaning?

- Who is the target audience? How do you know?

Freewrite for 10-15 minutes on these prompts.

Case Study – The Selfridges Story: A Look at the Visual Culture of Department Stores

To understand the complex layers of visual culture that play into the worlds of consumption, advertising, and branding, we will explore the example of Selfridges, the London department store that opened its doors in 1909.

The rise in popularity of department stores throughout the modern era is related to our study of visual culture in a number of connected ways. Advertising, visual displays of tantalising goods, and the architecture of shopping all work together to create a desire for consumer goods in these kinds of social spaces.

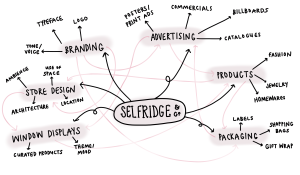

The diagram above points to the many complex layers of branding that exist for a store like Selfridges. Think about how products, advertisements, packaging, catalogues, store design, window displays, commercials, billboards all contribute to a department store’s visual identity. Notice something these elements all have in common? They are examples of visual culture! Department stores are rich examples for thinking critically about the connections that exist between visual culture and consumption.

So let’s jump in and learn a bit more about Selfridges!

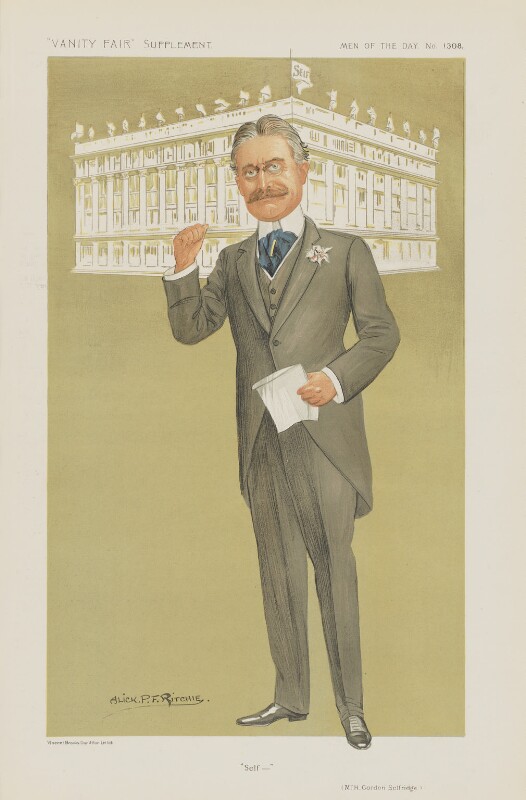

The year is 1879, and Harry Gordon Selfridge arrives in Chicago where he takes a job at Marshall Field’s, Chicago’s largest department store. Mr. Selfridge spent 25 years climbing from entry level employee to junior partner and learned everything he could about the industry, implementing innovations that were specifically aimed at targeting women customers, an often overlooked category of shoppers at the time.

In 1906, Harry visited London, England. Naturally, he made a point of visiting rival department stores, and he quickly realised the differences between English and American stores. Selfridge thought the English stores were old-fashioned and stuffy and he saw an opportunity to bring modern American glamour and convenience to England.[1]

In the early 20th century, London’s West End was a commercial hub filled with stores, of course, but also many examples of visual culture–posters, billboards, electric signs, window displays, and advertisements lined the streets. What better place than this to begin a commerce empire?

Selfridge wasted no time developing his retail palace. By 1909, he had a store in London that occupied a whole city block of this coveted location, with eight floors, a hundred departments, multiple restaurants, a post office, and several resting places like clubs, libraries, a rooftop garden, an ice rink, and even a shooting range! It also had ladies washrooms, which may not seem like a novelty to us today, but was for English department stores at this time.[2]

The store, called Selfridge’s for obvious reasons, was eighty feet tall with enormous glass windows and a facade of neoclassical columns that dominated the urban sprawl with its stately and imposing presence. Inside, visitors were greeted by welcoming staff who quickly learned Selfridge’s motto, “the customer is always right.” The store featured bright lighting, high ceilings, and extravagant merchandising displays.[3]

On opening day, Selfridge filled the store with flowers, and even hired orchestras to play throughout the showrooms.[4]

Image Source: Finnish Heritage Agency, (CC BY 4.0)

Selfridge was such a character that his story was adapted to the screen–let’s take a break and watch a trailer for the 2013 ITV show Mr. Selfridge. While you are watching, take note of how you might have felt entering a store like this one. What would the experience be like, and how many different layers of visual culture might you find?

Selfridge was focused on bringing spectacle, pleasure, and status to the shopping experience rather than positioning it as a simple, practical household task that had to be crossed off a list.[5] The skilled and deliberate use of visual culture helped him achieve this. His shop quickly became appealing to for many women in the Edwardian era as they experienced new levels of freedom in the public sphere.[6]

By designing his store to be a luxurious space with mass-produced products made to seem like they were one-of-a-kind amidst a vast range of extravagant amenities, Selfridge positioned shopping as a social opportunity for women to participate in metropolitan cultural happenings, urging them to aspire to a fanciful life that could be attained by spending money in his store. He hid this motive beneath a veil of accessibility, making his store open to all and the various rooms within it free to visit with no monetary tips allowed. Customers were invited to explore the space with no obligations to purchase anything, mingling with women of different social classes.[7]

We must again think critically about this notion of being “open to all,” since racism and racial politics had an influence on who could actually visit such social spaces comfortably. For example, in Philadelphia during the mid 20th century Black women were not permitted to work in department stores. We will return to the Selfridge story now, but this is another example of how contextual analysis can give us a broader and more detailed picture of the visual culture we are investigating.

Selfridge was a master of advertising. He sent out personal invitations to the store opening, about 600,000 of them. He also developed 32 illustrated advertisements that were shared in newspapers throughout the store’s first week, inviting everyone in England to visit Selfridge’s.[8] He also established a prominent media presence that spread his reach to the masses.

Selfridge had successfully captured peoples’ attention, but what was his message? For Selfridge it was that shopping was a pleasure, and he was intent on convincing all of England that this was the case. All the delights of London were now in one place–women, in particular, were invited to come to shop, eat, relax, socialise, and be entertained. Women customers were treated with the utmost respect and made to feel as comfortable and important as possible.[9] The store also relied heavily on women employees, so whether working, shopping, or visiting, Selfridge’s was deeply ingrained in the modern woman’s experience of Edwardian London and the store’s success was largely dependent on the support of this demographic.

Mr. Selfridge succeeded in establishing a new way of shopping in London, and he pushed forward the business of department stores dramatically. Visual culture was an important part of this and the continued visual experience of retail culture owes much to the Selfridge story–he had an immeasurable impact on the way commercial culture developed, and Selfridges still stands today as a premier shopping destination in London.

What was it about Harry Gordon Selfridge’s approach that was so different? Firstly, he recognized an opportunity to breathe new life into England’s retail environment and he capitalised on the societal shift towards luxury, pleasure, and social mobility. He positioned mass produced goods in extravagant spaces, creating the impression that these goods were exclusive, coveted, and unique, simply through his branding and the environment he created in London’s West End.[10]

Secondly, he developed his business at a time when the media was growing, and the press was powerful. Selfridge was very intentional about his advertising strategies, so he defined his brand and used marketing to spread his vision to the masses. Lastly, Mr. Selfridge taught a generation how to think about shopping in a way that benefitted the retailer and pushed an agenda of consumption under the guise of an idealised and just-out-of-reach lifestyle.[11] Selfridge was a key proponent in the push for the public to conceptualise buying things as a leisurely pastime, and to connect consumption with the idea of personal satisfaction.This narrative was particularly aimed at women of the time, and developed due to decades of societally-imposed expectations around gender roles.

The High Cost of Fashion

Now, having learned about Selfridge’s use of advertising, branding, and customer experience to drive sales and encourage consumerism, we should shift towards evaluating the impacts of this spike in consumption. Of course, Selfridge’s is only one example of one department store, but there are countless other department stores and many more stand-alone brands and shops that sell these same types of goods. Our world is saturated with products, and shopping has only become more convenient through the rise of online shopping. With advertisements convincing us we are always in need of new things, and brand identities telling us that we will achieve our dream lives if we purchase their products, we have become lulled into a cycle of consumption that is accelerating at unsustainable speeds.

Advertisements strive to satisfy our desires, but often these desires are created by brands in the first place. Advertisers rely on our socially-induced insecurities to feed into a desire for something more/new/better. Ads often promise a better life, but in fact there is evidence to suggest that advertising can lead to unhappiness.

Further, advertising can distract us from the realities of our consumption. Do we really need another pair of shoes? Will they end up in a landfill? Are there other environmental considerations to think about? Where were they made, and with what materials? Are the brand’s practices ethical? Indeed, a brand’s messaging can disguise the dark sides of consumerism, such as a disregard for environmental, humanitarian, and other unethical production violations.

Documentary films such as True Cost attempt to raise awareness of these issues, encouraging consumers to examine their consumption practices and push for change. As films like this emphasise, the impact of this seemingly-endless cycle of consumption is not felt equally around the world. Wealthy countries use and dispose of goods at record speeds, while those in other parts of the world are often left with the burden of producing these goods as well as the unethical systems, pollution, and humanitarian crises that often come with this task.

Seeking Alternatives to Contemporary Fast Fashion

There is no doubt that clothing is an important part of the visual image we present of ourselves to the world. Today many people are looking for more sustainable alternatives to the mainstream fashion industry, and there is a growing interest in things like slow fashion, upcycling, and historical techniques for making clothing. (And good news for those of you who enjoy thrifting–research suggests you are likely more stylish!)

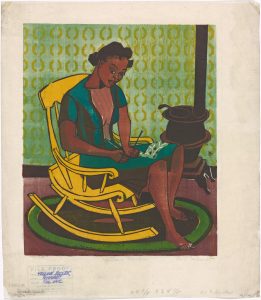

Image Source: New York Public Library, Public Domain

Image Source: New York Public Library, Public Domain

Events like Indigenous Fashion Week highlight the work of Indigenous designers while also taking a political stance against the damaging practices of the world of mainstream consumer fashion while a revival in traditional beading techniques has connected many Indigenous people with aspects of their history and culture.

A Stitch in Time is a television show that explores how historical garments were made in previous eras as a way to reveal a deeper understanding of the society they came from–another excellent example of contextual analysis at work.

Reflection Exercise

Watch the first 5 minutes of the first episode of A Stitch in Time (or the whole episode if you are interested!). This episode explores the wardrobe of Charles II, and his foray into what is now considered the invention of the modern three piece suit. This clip will give you a sense of the rich history held within clothing and painting–and their connections to visual culture–demonstrating an approach to fashion very much unlike that which we experience today. The process of production is so intricate and in watching this show, you can start to gain a deeper appreciation for the skilled labour that goes into making a high quality garment.

After watching the clip (or episode), spend 10-15 minutes freewriting on the topic of fashion and visual culture. Did this video raise any questions for you–perhaps not necessarily on Charles II but about the broader links between fashion, production, and visual culture? Is there a type of clothing that you would be interested in investigating in this level of detail? What time period is it from? What part of the world? What interests you about it?

Note: if you need inspiration, a browse through the online collections of The Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Costume Institute might do the trick!

Material Culture and Crafting

Material culture is similar to visual culture, but it is focused on objects and how people use them. Objects studied by scholars focusing on material culture range from everyday items like cups and bowls to luxury items made with materials such as glass, jewels, and gold. The study of clothing and textiles also falls under the umbrella of material culture. The McCord Stewart Museum in Montreal is an example of a museum with an extensive collection of material culture, much of which has been digitised.

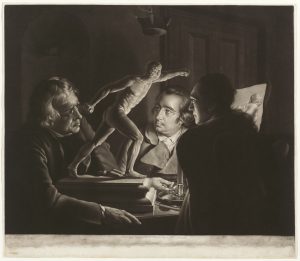

Image Source: McCord Stewart Museum, Public Domain

Image Source: Art Institute of Chicago, Public Domain

Crafting Communities is a network of scholars who focus on 19th century material culture techniques. They have created online resources and tutorials with the intent of teaching people how to make objects and items using historical techniques. A tutorial on making broderie anglaise, for example, combines text, image, and video as a way to illustrate how eyelet lace would have been made. (Feel free to try it out for yourself if you have the time and materials!) We can see this type of lace on the dress Missie Burbage wore for her portrait session at the William Notman & Son studio in Montreal in 1887.

Through these types of resources we can reflect on the effort and time required to create these detailed fabric treatments, and compare this with the whirlwind clips we saw of the Mr. Selfridge show and the True Cost documentary. There is quite a difference in pace!

We can also consider the work of Canadian fashion historian Ingrid Mida. She is a proponent of slow looking, a practice of observing closely and slowly as a way of studying objects. To carry this out, Mida draws her objects of study rather than photographing them. This intentional shift in perspective encourages a new way of thinking about the things around us, and urges us to appreciate material goods in a new way.

Reflection Exercise

In this exercise we are going to practice slow looking. To do so, you will need to find an everyday item in your home that you consider disposable. This could be something you buy frequently or consider to be mundane and low in value (like a tube of toothpaste, a pair of flip flops, or even a cheap t-shirt).

Now dedicate 5-10 minutes drawing that item. It doesn’t matter if you aren’t an artist–nobody will see this drawing but you. The point here is the process, not the finished product.

As you draw, consider where your item came from, the materials used to produce it, and its role in your life. What questions do you have about this object, information that might not be immediately apparent as you look at it. The goal here is to reflect on our consumption practices and mindfully engage with the things we are purchasing.

- Jeremy W. Kilar, “Mr. Selfridge: Harry Selfridge’s Michigan Years.” Michigan History Magazine 101, no. 5 (2017): 24. ↵

- Richard Cavendish, “MAR 15 1909: The Opening of Selfridge’s Department Store.” History Today 59, no. 3 (2009): 12.; Erika Diane Rappaort, Shopping for Pleasure : Women in the Making of London’s West End (Princeton, N.J: Princeton University Press, 2001), 154. ↵

- Jeremy W. Kilar, “Mr. Selfridge: Harry Selfridge’s Michigan Years” Michigan History Magazine 101, no. 5 (2017): 24; Erika Diane Rappaport, Shopping for Pleasure : Women in the Making of London’s West End (Princeton, N.J: Princeton University Press, 2001), 154. ↵

- Richard Cavendish, “MAR 15 1909: The Opening of Selfridge’s Department Store.” History Today 59, no. 3 (2009): 12 ↵

- Richard Cavendish, “MAR 15 1909: The Opening of Selfridge’s Department Store.” History Today 59, no. 3 (2009): 12 ↵

- Kilar, Jeremy W. Kilar, “Mr. Selfridge: Harry Selfridge’s Michigan Years.” Michigan History Magazine 101, no. 5 (2017): 24; Erika Diane Rappaport, . Shopping for Pleasure : Women in the Making of London’s West End (Princeton, N.J: Princeton University Press, 2001), 156-157. ↵

- Traci Parker, Department Stores and the Black Freedom Movement : Workers, Consumers, and Civil Rights from the 1930s to the 1980s. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2019. ↵

- Richard Cavendish, “MAR 15 1909: The Opening of Selfridge’s Department Store.” History today 59, no. 3 (2009): 12; Erika Diane Rappaport, Shopping for Pleasure : Women in the Making of London’s West End (Princeton, N.J: Princeton University Press, 2001), 157-158. ↵

- Erika Diane Rappaport, Shopping for Pleasure : Women in the Making of London’s West End (Princeton, N.J: Princeton University Press, 2001). 161-162. ↵

- Elizabeth Outkah, “Crossing the Great Divides: Selfridges, Modernity, and the Commodified Authentic,” Modernism/modernity Vol 12, no. 2 (2005): 311–328. ↵

- Erika Diane Rappaport, Shopping for Pleasure : Women in the Making of London’s West End (Princeton, N.J: Princeton University Press, 2001), 168-169. ↵