6 Power and Resistance

J. Keri Cronin and Hannah Dobbie

As we saw in the previous chapter, visual culture can be used to reinforce systems of inequality and power. The concept of “the gaze” is an important part of this. But visual culture can also be part of a resistance to these systems. In this chapter we are going to take a closer look at how visual culture can enforce, uphold, and also challenge systems of power in our world. We are going to work through some examples to help illustrate ways that systems of power are constructed, negotiated, and challenged through visual culture. As with all of the chapters in this book, the examples presented here are for illustrative purposes. What these investigations provide are a framework for you to then apply these concepts to other images and examples.

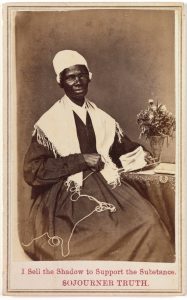

“I Sell The Shadow to Support the Substance”

Sojourner Truth’s portrait is a good example here. Truth was born into slavery in the late 18th century and “walked away by daylight” after the New York Anti-Slavery Law legally gave her freedom in 1827. She became a passionate speaker, an abolitionist, and a supporter of the growing women’s rights movement.

Here she uses photography as a way to “look back,” to make herself visible. This is particularly relevant given her lived experience as an enslaved person. Systems of slavery were reinforced and upheld through visual culture and surveillance–from fugitive slave ads to the “overseer” who supervised the work on plantations. For Truth to engage in the use of visual culture as a tool of empowerment is incredibly significant.

She specifically chose the carte-de-visite format, a popular form of photography during the 19th century that was intended to be collected, shared, and exchanged–a visual “calling card” and collectible item. Sojourner Truth sold these cartes-de-visite to make money, but they also allowed her to have control over how she was seen. The inclusion of the words “I sell the shadow to support the substance” speaks to her knowledge of the power of imagery–she was very aware that her image was collectible, and sold it to fund her work. Here she is still being looked at, but the power dynamics are different. This is not a system of surveillance, she is in charge.

Visuality and Countervisuality

Nicholas Mirzoeff, a Professor at NYU, has written about “visuality” and “countervisuality” in his book The Right to Look. This book provides an important framework for thinking about the complex ways that images shape power structures and reinforce inequities. Visuality here goes beyond the biological processes involved in seeing. Rather, in Mirzoeff’s theoretical framework, there is critical consideration of how structures that support who is being looked at have a long history of being linked to systems of oppression. One of the examples he turns to here is slavery. Countervisuality is a process deeply steeped in critical thinking, resisting, and challenging the way that these systems of visuality have historically normalised deeply rooted inequities in our world.

An exhibition of artwork by Kapwani Kiwanga provides a good example to illustrate these concepts. Off-Grid was recently installed at the New Museum in New York City. This installation responds to the long history of surveillance of Black bodies–from “lantern laws” that required unaccompanied enslaved peoples to carry a lantern so they were visible at night to contemporary surveillance technologies used by law enforcement today.[1] Two sculptural pieces make up this installation, Cloak and Maya Bantu. Notably, the artist requested that the normally bright lights of the gallery were shut off for this installation so the pieces were made visible only through the natural light coming into the space.

Reflection Exercise

Read Zoë Hopkins’s piece on Kapwani Kiwanga’s Off-Grid exhibit in Hyperallergic. As you read, consider how the artist has carefully thought about things like the materials used and the way the installation looks.

Now freewrite for 10-15 minutes on this art installation. As always, your freewriting can take any direction, but if you don’t know where to begin, the following prompts can help get you started:

- What thoughts came up for you as you read this article?

- How does the topic of the installation get reinforced through the artist’s choice of materials and display techniques?

- Does this exhibition make you think of other forms of visual culture?

- How do the concepts of visuality and countervisuality inform our understanding of these pieces?

Visual Culture and Biometrics

Image Source: Wellcome Collection, Public Domain

Visual culture and law enforcement have a long and complex history. From CCTV to cop shows, we have come to expect this relationship between imagery and policing in our current times, but many of the ways that visual culture is used in law enforcement today have roots in previous eras.

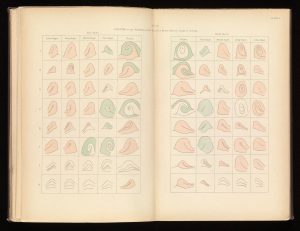

For example, the work of Francis Galton, a 19th British scientist and eugenicist, has continued implications for modern policing techniques. He championed the idea of using fingerprinting as a system of identification, a technique still in use today

Galton also came up with a way of using photography to come up with visual guidelines for identifying “criminal types” which involved predicting the likelihood of criminal behaviour based on someone’s physical appearance. By combining a number of different photographs he arrived at a visual estimation of what he believed certain types of people looked like. This, of course, has deeply troubling implications. A person could be viewed with suspicion just because of the way they look, something that is still very relevant in today’s world.

(from Inquiries into Human Faculty and its Development, 1883)

Image Source: Wellcome Collection, Public Domain

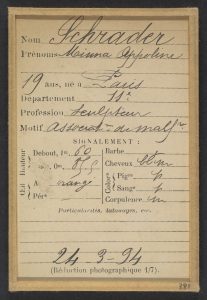

Mugshots have been in the news lately, but this type of visual culture also has roots in 19th century policing. Alphonse Bertillon, a French police officer, came up with standardised ways to document and categorise people arrested for crimes.

In the example below, Minna Schrader’s personal details are recorded on the back of her mugshot. We learn, for instance, that she was a sculptor and that she was 19 years old and had brown hair. She was arrested in 1894 as part of a crackdown on anarchist activities in Paris.

Mugshot photographs combined with a system of measuring bodily features such as the size of someone’s head or the distance between their eyes became known as the Bertillon system. Special devices were created to ensure standardisation of this practice.

Image Source: Wellcome Collection (CC BY 4.0)

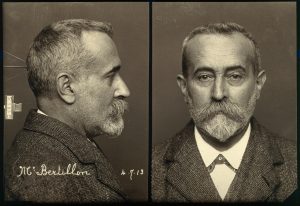

In the example below, Bertillon used his own image to demonstrate a system of posing (profile and front view of the face) that he believed would best aid in identification. This system is still part of the creation of mugshots today.

Image Source: Wellcome Collection, Public Domain

Bertillon’s systems of measuring and organising information about people arrested are part of a larger system of knowledge known as biometrics–the use of data, information, and measurements from human bodies. Systems of biometrics continue today with things like facial recognition technology being adopted in more and more situations even amid concerns about how this form of visual culture might lead to racial profiling.

American artist Martine Syms hosts a fascinating podcast called “Mirror With a Memory” through which she explores the connections between photography and artificial intelligence. She has an episode that focuses specifically on biometrics and in that episode she opens by asking viewers to consider the way many newer mobile phones rely on facial recognition technology as a security system. Many of us do this without thinking through the larger implications and this episode is certainly worth a listen!

Public Monuments

In recent years sculptures and monuments in public spaces have received much media attention. For example, a statue of John A. Macdonald, Canada’s first Prime Minister, was pulled off its pedestal during an Montreal anti-racism demonstration in 2020. This was just one of many instances where there has been resistance to the continued veneration of Macdonald, especially in light of his role in the creation of residential schools in Canada. The Graphic History Collective, a group of artists, scholars, and educators who use comics and graphic art to push for social change created a poster explaining Macdonald’s role in the creation of residential schools, and numerous school boards and municipal governments are grappling with how best to address Macdonald’s legacy today. In Montreal, it was decided that the broken statue of Macdonald would not be placed back in the spot it stood since 1895 but instead that a plaque would be placed on the empty pedestal. The statue will be repaired and the City of Montreal is currently in the process of finding a home for it in a museum.

In a similar situation, a statue of Edward Colston, a slave trader from Bristol, was pulled down in a Black Lives Matter protest in June of 2020, although this was not the first time the statue had been a target of anti-racist sentiment. After the statue of Colston came down another statue was put in its place, a sculpture of BLM protester Jen Reid by Marc Quinn. The piece is titled Surge of Power and its presence in the place where Colston’s statue once stood made a powerful statement. Quinn’s statue was removed shortly after it was installed because it hadn’t been approved by the municipal government.

The damaged statue of Edward Colston was put on display–graffiti and all–at Bristol’s M Shed museum alongside signs and other artefacts from the protest. This display allowed for this additional context and meaning now associated with the statue to be discussed in a broader forum. Historian David Olusoga has pointed out the importance of this, noting that this curatorial strategy “speaks to multiple periods in its history and Bristol’s history.”[2] This is an important point and one that links back to something we considered earlier in this course, namely that meaning is not fixed and static when it comes to visual culture. It can and does shift, new layers can be added.

These kinds of statues are not merely decorative. They commemorate certain individuals and the values they held, values that many have challenged. The examples above (the John A. Macdonald statue in Montreal and the Edward Colston statue in Bristol) are just two of many examples of conversations being held about how to deal with these complex topics today. Further, research has shown that these kinds of monuments can have a lasting political impact. For example, the presence of Confederate monuments in the United States has been shown to have an impact on contemporary voting patterns.

Repatriation

The repatriation of cultural artefacts to the communities who rightfully own them is another example of how visual culture is steeped in discourses of power and resistance.

One of the aspects of colonialism in Canada that has been in the headlines in recent years is the return of Indigenous cultural objects. Throughout the 19th and early 20th centuries, items like totem poles were removed from Northwest Coast Indigenous by anthropologists and collectors. Many of these items ended up in museum collections across Canada and around the world.

The removal of cultural artefacts by European and Euro-Canadians was steeped in systems of colonial power and the return of some of these items back to their communities has been a long and complex process. The video below entitled “Why Totem Poles Were Never Meant To Be In Museums” documents the repatriation of a totem pole to the Nuxalk Nation.

Perhaps the most well-known case involving the push to repatriate cultural objects is the ongoing calls for the British Museum to return marble sculptures taken from the Parthenon in Athens by Lord Elgin in 1801. An episode of the podcast “Stuff The British Stole” outlines the history of the ongoing controversy over these pieces.

Reflection Exercise

Take some time to watch the video (“Why Totem Poles Were Never Meant To Be In Museums”) and listen to the podcast (“Stuff the British Stole”) linked above. After you have done so, do 10-15 minutes of freewriting on each.

You can write about any aspect of these discussions that interested you, but if you don’t know where to start, here are some prompts to consider:

- Had you heard about either of these examples before? If so, when/where? If not, why do you think that is the case?

- Did you learn anything new by watching/listening to these examples?

- How do these examples relate to the theme of this chapter, “power and resistance?”

- Zoë Hopkins, “Kapwani Kiwanga Uses Daylight to Expose Racial Surveillance,” Hyperallergic (September 29, 2022): https://hyperallergic.com/764845/kapwani-kiwanga-uses-daylight-to-expose-racial-surveillance/ ↵

- [Damien Gayle, “ ‘A Potent Historical Artefact’: The Statue of Edward Colston’s New Role,” The Guardian (June 4, 2021): https://www.theguardian.com/world/2021/jun/04/edward-colston-statue-potent-historical-artefact-david-olusoga ↵