3 Visual Technologies and the Complexity of Truth

J. Keri Cronin and Hannah Dobbie

Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International (Wikimedia Fonds Françoise Foliot)

When we conduct a visual and/or contextual analysis, one of the important things we have to consider is the type of image we are working with. Is it a photograph? A painting? A sculpture? Something else?

Why does it matter? The medium (a fancy way of saying “type of image”) often shapes the way we come to understand an image. We often hold assumptions or expectations about how different kinds of images work in our world. For example, we might think a photograph is more closely linked to ideas of truth than, say, a drawing might be. But is this really the case? Why do we think this?

The answer has a lot to do with different technologies of image making. Throughout the history of visual culture we find countless examples of artists and image-makers who have adopted the latest visual technologies available to them in order to create images that appear more “real” or more “true-to-life” than those made using older technologies. This was as true in previous eras as it is today.

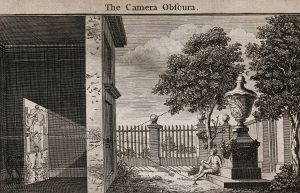

Camera Obscura

Image Source: Wellcome Collection, Public Domain

Devices such as the camera obscura have been used by artists to help create more “realistic” looking images. The above image is a representation of a camera obscura at work. As we see here, early camera obscuras were essentially large dark rooms (the term “camera obscura” means “dark room”). The artist would have to go inside the room in order to use this device.

These early versions of the camera obscura had a small opening on the wall which served as the lens. The science of optics is at work here: the scene on the outside of the camera obscura is projected onto the inside wall of the chamber. An artist could then trace that projection to make a sketch. This, of course, was a very limited form of image production as one could only use this technique to draw what was immediately outside the camera obscura.

Also, as you can see in this example, the image is projected upside down on the wall as this is how it naturally appears without the aid of any lenses. We know that by later in the 16th century the technology to “correct” this was known. For instance, Giovanni Battista Della Porta, a 16th century Italian scholar, wrote about using lenses for the camera obscura in his book, Magiae naturalis (“natural magic”).

The optical principles of a camera obscura have been known for centuries. In the 4th century BCE a Chinese philosopher named Mozi (born c. 470 BCE, died c. 391 BCE ) wrote about this. Aristotle (born 384 BCE, died 322 BCE) made reference to the basic principles of the camera obscura in his writings, and Alhazen (Abu Ali al Hasan ibn al-Haytham. born c. 965, died c. 1040) wrote about the optical principles of camera obscuras in Kitab al-Manazir (Book of Optics) between the years 1011 to 1021. A famous description of a camera obscura was written by Leonardo da Vinci (born 1452, died 1519) and can be found in the Codex Atlanticus, a collection of his writings and drawings housed in the Biblioteca Ambrosiana in Milan. The actual term “camera obscura” was coined by Johannes Kepler, the 17th century German scientist.

Over time, the camera obscura became smaller and more portable. Kepler had a tent-like camera obscura, and by the 18th and 19th century camera obscuras resembled wooden boxes. These smaller, more portable versions had a piece of glass that the image was projected on to. An artist could place a piece of paper on the glass and trace the image. This could then be used to further sketch out a painting or larger composition. This method allowed for artists to achieve realistic-looking linear perspective in their images.

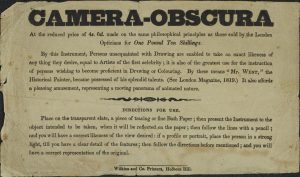

Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 Licence

Note how the advertisement below speaks to this idea of creating realistic looking images: “By this Instrument, Persons unacquainted with Drawing are enabled to take an exact likeness of any thing they desire…”

Image Source: Science Museum Group

Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 Licence

This painting by Charles Amédée Phillippe Van Loo speaks to the fascination with this kind of image-making technology, but it also offers a playful look at the relationship between two different kinds of image-making technologies. Here we have a portrait of a woman and two younger children. The young boy seems to be completely oblivious to the presence of the artist who was painting the portrait—all of his attention is on the wooden camera obscura.

In this painting the artist is playing with ideas of “realism.” Not only does he reference the technology of the portable camera obscura, but he also plays with the illusion of realism in a painting made using linear perspective. The figures extend beyond the frame that surrounds them. They seem to move into the viewer’s space. This kind of representation indicated that the artist was very aware that techniques to create ideas of “realism” or “realistic-looking” images were themselves open to interpretation. Here he moves beyond conventions of painting as if to draw attention to the fact that illusions of realism in art are just that–illusions.

The British artist David Hockney launched a storm of controversy with a book and film called Secret Knowledge: Rediscovering the Lost Techniques of the Old Masters. Hockney presented a carefully demonstrated argument about his belief that some of the most famous artists throughout history used camera obscuras to assist them with drawing and painting. Hockney is excited by this knowledge–why wouldn’t artists use the latest technology available to them? However, others are furious at the suggestion that beloved artists like Caravaggio, Diego Velázquez, and Johannes Vermeer used a tool like the camera obscura to help them create realistic-looking paintings.

There are a number of places where you can see what the world looks like through a camera obscura. In addition, contemporary artists like Abelardo Morell, Dianne Bos, and Liz Sales, are using camera obscuras in their work today. (Liz Sales even came and did a workshop with students at Brock University in 2016!)

Perhaps you might even want to try making your own camera obscura!

Reflection Exercise

Why do you think that David Hockney’s argument about some of the most famous artists in history using camera obscuras is so controversial? (Follow the links in the text above for more context).

Do some freewriting on this topic for 5-10 minutes. Afterwards read back what you wrote. Did anything surprise you in your writing practice today?

Depicting a World in Motion

In the late modern period (roughly the 18th century through to the First World War) there was a growing interest in depicting motion, especially amid the hustle and bustle of modern life in large urban centres like New York City. These city spaces were loud, noisy, and crowded, but they were also brimming with excitement and energy.

Image Source: New York Public Library, The Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs: Picture Collection, Public Domain

The development of cinema and moving pictures is very much related to this historical moment, but before these technologies were invented there were other attempts to create pictures of motion.

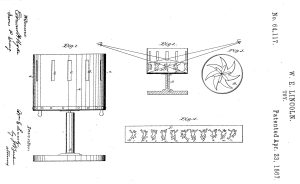

The Zoetrope was one such invention. It involved strips of still images (like the example below of the dog) printed in sequence. They were then placed in a cylindrical device that was spun. The motion of the machine made the pictures on the strip appear as if they were moving.

Image Source: Cooper Hewitt Smithsonian Design Museum (Museum purchase through gift of Mrs. E. Henry Harriman), Public Domain

As is the case with the camera obscura, some contemporary artists are bringing this older technology into their work. Artists like Eric Dyer and Veerle Coppoolse have brought the basic principles of the Zoetrope into their work.

Reflection Exercise

Why do you think some contemporary artists are interested in using older technologies in their work? How do these decisions related to concepts like “true,” “real,” and “authentic”?

Freewrite for 5-10 minutes on this prompt.

Can you think of (or find) other examples of artists working today who are drawing on older ways of making images?

Everyone a Photographer?

In 2019 the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam published a book called Everyone a Photographer? It was about the rise of amateur photography in the Netherlands, but the title poses an interesting question that has a broader relevance.

So many of us have easy and constant access to a camera through devices like our smartphones. We take pictures of our surroundings and our day-to-day experiences like never before. Many of these images are shared through social media and other online channels. A study done in 2020 notes that at that time approximately 3.2 billion images and 720,000 hours of video content are shared each day. These numbers are very likely increasing with each passing year.

The history of photography as a visual medium is both fascinating and complex, and there are a wide range of processes and technologies that fall under the big, broad, catch-all term “photography.” Historic, analog photographic processes and cameras are certainly having a moment. They are becoming more and more popular with artists these days so you may find yourself wishing to experiment!

Photography is a powerful medium that has had incredibly profound impacts on how we see the world. There are separate courses that focus exclusively on the history of photography, so this course won’t repeat that content here. (Note: If you are a student at Brock University you can study the history of photography in VISA 2P53.) You can also get a good overview of the history of photography through podcasts and videos. However, just for context here are a few key points:

- Most historians agree that the modern era of photography began in 1839 with the public announcement of a process known as the daguerreotype. This process is named after the inventor of the daguerreotype, a man named Louis-Jacques-Mandé Daguerre. However, it is important to note that Daguerre was not the only one who had been trying to figure out how to make photographs.

- The basic principles of cameras (using light to create an image) were known for hundreds of years before the announcement of the daguerreotype (see above section on the camera obscura). What was missing was a way to make a permanent recording of the image.

- The word “photography” was coined by Sir John Herschel who took the Greek words for “light” and “drawing/writing” and combined them to come up with “photography.”

(Salted paper prints from paper negatives, 1846) Image Source: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Public Domain

The images above show us the photographic business of one of the medium’s pioneers, a man named William Henry Fox Talbot. These pictures were staged for the camera and made using one of the early photographic processes that Fox Talbot invented, the calotype, which resulted in a paper negative.

Note the size of the cameras and tripods being used here! Early photographic equipment was often cumbersome and the processes used frequently relied on specialised knowledge and chemicals. In the early days of photography this type of image making really was the domain of inventors, professionals, and experts.

It wasn’t until the invention of the Kodak camera in 1888 that photography opened up to amateur photographers. The Kodak camera was portable, affordable (for middle class citizens), and, most importantly, it was designed so that you didn’t require specialised knowledge to take pictures. Kodak’s slogan was “You press the button, we do the rest.” What this meant is that people could take pictures with their Kodak camera and then when the film was done it got sent away for processing. No need to keep smelly, messy, and dangerous chemicals in the home! The Kodak camera came preloaded with film, and you could take 100 pictures with it before having to send it away to be developed.

Image Source: Library of Congress

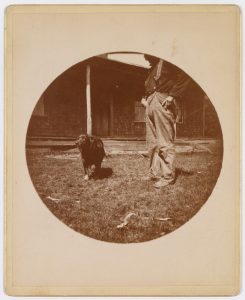

The pictures taken with the original Kodak camera are circular. If you see a circular photograph from the late 19th century in a museum or online collection, there is a good chance it was taken with one of these early Kodak cameras.

The Kodak camera really kick-started the era of photography as a popular medium for a wide segment of the population. Casual snapshots of friends, family, outings, and pets were popular–much like how many of us use the cameras on our phones today. The technology may have changed, but the desire to document the world around us has not.

Image Source: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Public Domain

Does the camera lie?

Take a close look at the photograph above. Besides the distinct round shape of it, what do you notice?

This is not a carefully composed, staged photograph. The man’s head is cropped right out of the picture! The dog is looking the other way. There is debris on the lawn. This seems like an unplanned snapshot, a slice of “real life.” It is far from a “perfect” picture, but it is a compelling and familiar image.

And yet there is also so much this photograph can’t tell us. We don’t know who this man is, we don’t know where the image was taken, we don’t know who took it, nor do we know the dog’s name. Further, we don’t know what exists just outside the frame. What else has the photographer cropped out? Did they decide to crop the man’s head out on purpose, or was that an accident? What was the relationship between the photographer and the man in the picture? Did the photographer love the dog or were they, perhaps, annoyed with it for messing up their garden? We simply don’t know. This picture can not answer these types of questions for us.

In addition, when we look closely and conduct a visual analysis we notice that this is a monochromatic image. In other words, it isn’t rendered in full colour the way many of us see the world.

Reflection Exercise

Is this Kodak photograph of the man and dog “true”? Why or why not? List all of the reasons you can think of to support your answer.

Write for 5 minutes on this topic.

There has long existed an assumption that a photograph is somehow more truthful and accurate than other kinds of images. This often has to do with the mechanical nature of cameras. There is an assumption that, unlike painting or drawing, the person making the image is somehow more removed from the process because they are using a mechanical device instead of a pencil or paintbrush. In their book, Practices of Looking: An Introduction to Visual Culture, Marita Sturken and Lisa Cartwright refer to this as the “myth of photographic truth.”[1] What they mean here is that we need to be careful and critical thinkers when it comes to understanding the meaning that photographs make in our world. We need to ask questions about what we are seeing when we look at photographs just like we would with any other type of image. The relationship between photography and “truth” is complicated.

Photographs can tell lies! Even before computers, Photoshop, and editing apps were available, people were manipulating photographs. For example, Hippolyte Bayard, a French photographer, created a photograph in which he appeared to fake his own death in 1840. He even signed it! The image of the ghost above is a double exposure image, perhaps related to the interest in the supernatural that was popular in the 19th and early 20th centuries in England. And in 1917 Elsie Wright and Frances Griffiths, two young girls in England, took a series of photographs of what they claimed to be fairies although, in reality, the fairies were cardboard cutouts propped up by hatpins. Some people thought that the so-called Cottingley Fairy photographs were the real deal, including Sir Arthur Conan Doyle who is best known for his Sherlock Holmes stories.

Hannah Maynard was a photographer who worked in British Columbia in the 19th and early 20th centuries. While she produced many different types of images, she is best remembered today for her experimental photographs. In the image below she has put herself in the picture multiple times. This is a humorous picture, one version of Maynard focuses on pouring the tea while another looks out at us, the viewer. A third version of Maynard appears in a picture frame on the wall and is in the process of splashing tea on one of the seated versions of herself. We can imagine the fun she had as she planned and staged this photograph–especially in an era before digital tools like Photoshop!

These are just some of the many examples where photographs were “faked” or manipulated in the first century of the medium’s existence.

And yet even when we recognize this history of “doctoring” images, we still live in a world that places an incredible amount of faith in images generated by cameras. Think, for instance, about the role of photo identification in our world. We show our passports, driver’s licence, or student ID as a way to prove who we are. And yet racial biases implicit in the photographic process make this seemingly straightforward act fraught with complexity and controversy. This is also true for facial recognition technologies.

Photographs are also accepted as evidence in court, although there has long been recognition of the difficulty of assuming a photograph is true in this context. For example, in 1929 John H. Anderson Jr. wrote an article for the North Carolina Law Review called “Admissibility of Photographs as Evidence.” This article provides a fascinating look at the conversations around complexity of photographs in this type of environment nearly 100 years ago.

Anderson notes that there are a couple of important things to keep in mind when introducing photographs as evidence in court. First of all he stresses the importance of having “a witness who is familiar with the person, place, thing, or condition which the picture purports to represent” so that they “may testify that it correctly portrays this thing.”[2] Secondly, he notes that “the accuracy of the picture may be established by testimony of the photographer, that it is the result of a process mechanically reliable.”[3] Johnson recognizes both the unreliability of photographs (by stating the need to have someone who can testify that the image is reasonably accurate) and a collective sense of faith in the mechanical nature of the photographic process. This tension remains part of discussions about photographs to the present day.

Today, of course, we have tools like digital editing software and apps that can quickly and easily change and manipulate photographs. Artificial intelligence software can generate images that appear to be photographs, including very convincing and real “fakes.” Indeed, the very definition of photography seems to be shifting before our eyes. But it is important to remember that photographs have always been edited and manipulated. This is not unique to our current time. But what has changed is the ease and speed with which manipulated images can be widely shared. A recent study has drawn attention to just how pervasive the spread of visual misinformation is on social media platforms. It is also important to be aware of how things like racial and gender biases are being perpetuated through some of these new image-making tools. Again, this was not absent in earlier eras, but the way we interact with photographs across various platforms today means that we need to be informed and aware of the complexity of photographs rather than taking them at face value.

- Marita Sturken and Lisa Cartwright, Practices of Looking: An Introduction to Visual Culture. 3rd edition (New York & Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2018): 24. ↵

- John H. Anderson, Jr., “Admissibility of Photographs as Evidence,” North Carolina Law Review Vol. 7 no 4 (1929): 444-445 ↵

- John H. Anderson, Jr., “Admissibility of Photographs as Evidence,” North Carolina Law Review Vol. 7 no 4 (1929): 445 ↵