Chapter 6. Entertainment

Donna Owens

Learning Objectives

- Describe the nature and function of activities and businesses that provide entertainment for tourists in Canada

- Identify tourism entertainment activities by their industry groups

- Identify various types of festivals and events and ways in which these are funded and organized

- Describe the MCIT (meetings, convention, and incentive travel) component and its economic impact

- Review various types of attractions including zoos and botanical gardens

- List components of cultural heritage tourism including museums, galleries, and heritage sites

- List other experiences including sport tourism, agritourism, wine tourism, and culinary tourism

- Identify key industry associations related to the tourism entertainment sector and understand their mandates and the resources they provide

Overview

When a traveller enters Canada, there’s a good chance he or she will be asked at the border, What is the nature of your trip? Whether the answer is for business, leisure, or visiting friends and relatives, there’s a possibility that a traveller will participate in some of the following activities (as listed in the Statistics Canada International Travel Survey):

- Attend a festival or fair, or other cultural events

- Visit a zoo, aquarium, botanical garden, historic site, national park, museum, or art gallery

- Watch sports or participate in gaming

These activities fall under the realm of entertainment as it relates to tourism. Documenting every activity that could be on a tourist’s to-do list would be nearly impossible, for what one traveller would find entertaining, another may not. This chapter focuses on the major components of arts, entertainment, and attractions, including motion pictures, video exhibitions, and wineries, all activities listed under the North American Industry Classification System we learned about in Chapter 1.

Festivals and Events

Festival and Major Events Canada (FAME) released a report in 2009 detailing the economic impacts of the 15 largest festivals and events across Canada, which amounted to $750 million in tourist spending and another $300 million in local operational spending (Enigma Research Consultants, 2009). Let’s take a closer look at this segment of the sector.

Festivals

The International Dictionary of Event Management defines a festival as a “public celebration that conveys, through a kaleidoscope of activities, certain meanings to participants and spectators” (Goldblatt, 2001, p. 78). Other definitions, including those used by the Ontario Trillium Foundation and the European Union, highlight accessibility to the general public and short duration as key elements that define a festival.

Search “festivals in Canada” online and over 54 million results will appear. To define these activities in the context of tourism, we need to consider operations and marketing: in other words, we must answer the questions, Who are these activities aimed at? and Why are they being celebrated?

The broad nature of festivals has lead to the development of classification types. For instance, funding for the federal government’s Building Communities through Arts and Heritage Program is available under three categories, depending on the type of festival:

- Local festivals funding is provided to local groups for recurring festivals that present the work of local artists, artisans, or historical performers.

- Community anniversaries funding is provided to local groups for non-recurring local events and capital projects that commemorate an anniversary of 100 years (or greater, in increments of 25 years).

- Legacy funding is provided to community capital projects that commemorate a 100th anniversary (or greater, in increments of 25 years) of a significant local historical event or local historical personality.

In 2012-13, funds awarded to BC festivals ranged from $2,000 for the Nelson History Theatre Society’s Nelson Arts and Heritage Festival to $119,400 for the Vancouver International Film Festival (Government of Canada, 2014a).

Spotlight On: International Festivals and Events Association

Founded in 1956 as the Festival Manager’s Association, the International Festivals and Events Association (IFEA) supports professionals who produce and support celebrations for the benefit of their communities. Membership is required to access many of their resources. For more information, visit the International Festivals and Events Association website: www.ifea.com

Festivals and events in BC celebrate theatre dance, film, crafts, visual arts, and more. Just a few examples are Bard on the Beach, Vancouver International Improv Festival, Cornucopia, and the Cowichan Wine and Culinary Festival.

Spotlight On: Cornucopia, Whistler’s Celebration of Wine and Food

This festival is dubbed “the fall festival for the indulgent and the connoisseur.” It’s an 11-day showcase with seminars, tastings, gala events, and all things decadent. For more information, visit Cornucopia: http://whistlercornucopia.com

Events

An event is a happening at a given place and time, usually of some importance, celebrating or commemorating a special occasion. To help broaden this simple definition, categories have been developed based on the scale of events. These categories, presented in Table 6.1 overlap and are not hard and fast, but help cover a range of events.

| [Skip Table] | ||

| Event Type | Characteristics | Examples |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Mega-event: those that yield high levels of tourism, media coverage, prestige, or economic impact for the host community or destination. |

|

|

| 2. Special event: outside the normal activities of the sponsoring or organizing body. |

|

|

| 3. Hallmark event: possesses such significance in terms of tradition, attractiveness, quality or publicity, that it provides the host venue, community, or destination with a competitive advantage. |

|

|

| 4. Festival: (as defined above) public celebration that conveys, through a kaleidoscope of activities, certain meanings to participants and spectators. |

|

|

| 5. Local community event: generated by and for locals; can be of interest to visitors, but tourists are not the main intended audience. |

|

|

| Data source: Getz, 1997, p. 6 | ||

Events can be extremely complex projects, which is why, over time, the role of event planners has taken on greater importance. The development of education, training programs, and professional designations such as CMPs (Certified Meeting Planners), CSEP (Certified Special Events Professional), and CMM (Certificate in Meeting Management) has led to increased credibility in this business and demonstrates the importance of the sector to the economy. Furthermore, there are a variety of event management certifications and diplomas offered in BC that enable future event and festival planners to gain specific skills and knowledge within the sector.

Various tasks involved in event planning include:

- Conceptualizing/theming

- Logistics and planning

- Human resource management

- Security

- Marketing and public relations

- Budgeting and financial management

- Sponsorship procurement

- Management and evaluation

But events aren’t just for leisure visitors. In fact, the tourism industry has a long history of creating, hosting, and promoting events that draw business travellers. The next section explores meetings, conventions, and incentive travel, also known as MCIT.

Meetings, Conventions, and Incentive Travel (MCIT)

According to the Business Events Industry Coalition of Canada (BEICC), business events are big business. In 2012, they:

- Delivered at least $27 billion to Canada’s economy (1.5% of Canada’s GDP)

- Contributed $8.5 billion in taxes and service fees to all levels of government

- Created over 341,700 employment opportunities (average salary of over $50,000 per year)

The business events industry in Canada is as big as agriculture and forestry, and it provides nearly twice the number of jobs that telecommunications and utilities do (BEICC, 2014).

Take a Closer Look: BEICC Canadian Economic Impact Study

To learn more about the impact of business events, watch the BEICC Canadian Economic Impact Study video: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Hu6lcKF2iV4&feature=youtu.be

There are several types of business events. Conventions generally have very large attendance, and are held annually in different locations. They also often require a bidding process. Conferences have specific themes, and are held for smaller, focused groups. Trade shows/trade fairs can be stand-alone events, or adjoin a convention or conference. Finally, seminars, workshops, and retreats are examples of smaller-scale MCIT events.

Spotlight On: The Business Events Industry Coalition of Canada

The Business Events Industry Coalition of Canada (BEICC) is the national voice of the meetings and events industry in Canada, comprising organizations dedicated to the betterment and promotion of the meetings and events industry. For more information, visit the Business Events Industry Coalition of Canada website: http://beicc.com/

As meeting planners became more creative, meeting and convention delegates became more demanding about meeting sites. No longer are hotel meeting rooms and convention centres the only type of location used; non-traditional venues have adapted and become competitive in offering services for meeting planners. These include architectural spaces such as airplane hangars, warehouses, or rooftops and experiential venues such as aquariums, museums, and galleries (Colston, 2014).

Spotlight On: Meeting Professionals International

Meeting Professionals International (MPI), founded in 1972, is a membership-based professional development organization for meeting and event planners. For more information, visit the Meeting Professionals International website http://www.mpiweb.org or the Meeting Professionals International: BC Chapter website: http://www.mpibcchapter.com

Incentive Travel

For many people new to the travel industry, incentive travel is an unfamiliar concept. The Society of Incentive Travel Excellence (SITE) has explained that incentive travel involves “motivational and performance improvement strategies of which travel is a key component” (2014). Unlike other types of business events, incentive travel is focused on fun, food, and other activities rather than education and work.

Sectors that use incentive travel include insurance, finance, technology, pharmaceutical, and auto manufacturers and dealers. The incentive travel market is extremely competitive and demanding. When rewarding high-performance staff, Fortune 500-type companies are looking for the most luxurious and unique travel experiences and products available.

Take a Closer Look: SITE Crystal Awards

SITE holds annual awards for the best in unique, memorable incentive experiences. In 2014, the winner for Most Effective Incentive/Marketing Campaign, “Toyota Dealer Incentive – Elegant Escapes” was Aimia. To see the list of other winners, and for more information, visit the Site Crystal Awards: www.siteglobal.com/p/cm/ld/fid=181

Convention Centres

No discussion of business events would be complete without noting the importance of convention centres — very large venues that can host thousands of delegates.

Key success factors for convention venues include:

- Air access to the destination

- Quality hotels close to or adjacent to the venue

- Quality venue space

- Relative cost of the destination and venue

- Attractiveness of the destination

BC is home to a number of convention centres, including those in Kelowna, Nanaimo, Penticton, Prince George, and Victoria. The signature venue for the province is the Vancouver Convention Centre, which underwent a significant expansion prior to the 2010 Winter Olympics.

Spotlight On: The Vancouver Convention Centre

The Vancouver Convention Centre is owned and managed by the BC Pavilion Corporation (PavCo), a Crown corporation, and staffed with 70 PavCo employees, six official suppliers, and a further workforce of 291 full-time equivalent jobs. With its unique “scratch kitchen” that uses fresh, local products, an extensive recycling program, and its legendary “green roof,” the centre is known for its beautiful views and commitment to sustainability. For more information, visit the Vancouver Convention Centre: www.vancouverconventioncentre.com

With an understanding of the scope of festivals and events, as well as examples of the venues that host them, let’s turn our attention to the diverse number of attractions that contribute to the tourism entertainment sector.

Attractions

Without attractions there would be no need for other tourism services. Indeed tourism as such would not exist if it were not for attractions. (Swarbrooke, 2002, p. 3)

When the Canadian Tourism Commission planned a survey of Canada’s tourist attractions in 1995, there was no official definition of tourist attractions. After consultation, federal, provincial, territorial, and industry stakeholders agreed on a working definition: “places whose main purpose is to allow public access for entertainment, interest, or education” (Canadian Tourism Commission, 1998, p. 3).

Five major categories were established:

- Heritage attractions: focus on preserving and exhibiting objects, sites, and natural wonders of historical, cultural, and educational value (e.g., museums, art galleries, historic sites, botanical gardens, zoos, nature parks, conservation areas)

- Amusement/entertainment attractions: maintain and provide access to amusement or entertainment facilities (e.g., arcades; amusement, theme, and water parks)

- Recreational attractions: maintain and provide access to outdoor or indoor facilities where people can participate in sports and recreational activities (e.g., golf courses, skiing facilities, marinas, bowling centres)

- Commercial attractions: retail operations dealing in gifts, handcrafted goods, and souvenirs that actively market to tourists (e.g., craft stores listed in a tourist guide)

- Industrial attractions: deal mainly in agriculture, forestry, and manufacturing products that actively market to tourists (e.g., wineries, fish hatcheries, factories)

Although the data is two decades old (the survey was never repeated at a national level), the overall findings help to outline the importance of tourist attractions to Canada’s tourism industry. The 1995 survey found:

- Just over half (51%) of attractions charged admission (49% did not).

- Surveyed attractions saw 200 million visitors with 50% of volume in the summer.

- The majority (80%) reported visits lasted under three hours.

Major revenue sources for attractions include admission, merchandising, food and beverage sales, parking, grants, and donations. Major expenses include staff, land, insurance, permits and fees, marketing, equipment, and buildings.

The rest of this chapter explores various types of attractions in more detail.

Cultural/Heritage Tourism

The phrase cultural/heritage tourism can be interpreted in many ways. The Canadian Tourism Commission has defined it as tourism “occurring when participation in a cultural or heritage activity is a significant factor for traveling. Cultural tourism includes performing arts (theatre, dance, and music), visual arts and crafts, festivals, museums and cultural centres, and historic sites and interpretive centres” (LinkBC, 2012).

Take a Closer Look: The First Government of Canada Survey of Heritage Institutions

In late 2014 the Department of Canadian Heritage released its Survey of Heritage Institutions, which provides aggregate financial and operating data to governments and cultural associations. It aims to gain a better understanding of not-for-profit heritage institutions in Canada in order to aid in the development of policies and the administration of programs. View the full version of the report at

Government of Canada Survey of Heritage Institutions: 2011 [PDF]: www.pch.gc.ca/DAMAssetPub/DAM-verEval-audEval/STAGING/texte-text/2011_Heritage_Institutions_1414680089816_eng.pdf?WT.contentAuthority=6.0

A 2011 Government of Canada survey of heritage institutions found (2014b):

- Revenues for all heritage institutions in Canada exceeded $1.73 billion (65% of which was unearned revenues — grants, government funding, and donations)

- Sales in goods and services (gift shops, cafeterias, and other outlets) accounted for 37% of earned revenue, followed by admissions at 20%

- Three provinces — Ontario (44%), Quebec (25%), and Alberta (9%) — had the largest share of heritage institutions

- Approximately 48% of heritage institutions charged admission, and the average adult entry fee was $7

Volunteers at heritage institutions outnumbered paid staff by approximately three to one. Of the 128,000 workers in heritage institutions, approximately 96,000 were volunteers. The amount of time they donated (over six million hours) contributed to huge savings for institutions. These statistics indicate that volunteerism is a critical success factor for Canadian heritage institutions.

Overall attendance at heritage institutions totalled almost 45 million visits in 2011, with museums (21.5 million visits) being the most popular of all heritage institution types surveyed. There were also over 137 million online visits to all heritage institutions (captured for the first time in the history of the survey).

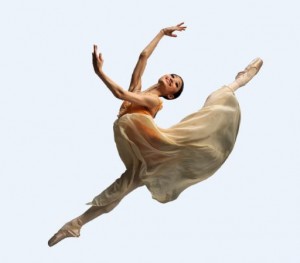

Performing Arts

Performing arts generally include theatre companies and dinner theatres, dance companies, musical groups, and artists and other performing arts companies. These activities and entities contribute to a destination’s tourist product offering and are usually considered an aspect of cultural tourism.

In 2011, the majority of small and medium-sized performing arts companies in Canada were profitable (86.3%). The average annual net profit was $28,300 (Government of Canada, 2014c).

British Columbia was home to 166 performing arts groups in 2012, and 103 of these were considered micro groups, indicating that this sector of the industry is dominated by small organizations with one to four employees.

Spotlight On: Made in BC

Made in BC: Dance On Tour is a not-for-profit organization committed to bringing touring dance performances, dance workshops, and other dance events to communities around British Columbia for the benefit of residents and visitors alike. Originally intended to showcase BC performers, it also brings touring groups from other regions to the province. For more information, visit Made in BC: http://www.madeinbc.org

Art Museums and Galleries

Art museums and galleries may be public, private, or commercial. According to the Canadian Art Museum Directors Organization (CAMDO, 2014), both art museums and public galleries present works of art to the public, exhibiting a diverse range of art from more well-known artists to emerging artists. Exhibitions are assembled and organized by a curator who oversees the installation of the works in the gallery space. However, art museums and public galleries have different mandates, and therefore offer different visitor experiences.

Art museums collect historical and modern works of art for educational purposes and to preserve them for future generations. Public galleries, on the other hand, do not generally collect or conserve works of art. Rather, they focus on exhibitions of contemporary works as well as on programs of lectures, publications, and other events.

A few examples of the art museums and public galleries in BC are the Vancouver Art Gallery, the Art Gallery of Greater Victoria, Two Rivers Gallery in Prince George, and the Kelowna Art Gallery.

Many of the smaller galleries have formed partnerships within geographic regions to share marketing resources and increase visitor appeal. One example includes the self-guided Art Route Tour in Haida Gwaii.

Museums

The term museum covers a wide range of institutions from wax museums to sports halls of fame. No matter what type of museum it is, many are now asking if museums are still relevant in today’s high-tech world. In response, museums are using new technology to expand the visitor experience. One example is the Royal BC Museum, which hosts an online Learning Portal, lists recent related tweets on its home page, and is home to an IMAX theatre playing IMAX movies that relate to the museum exhibits.

Spotlight On: Canadian Museums Association

The Canadian Museums Association (CMA) is the national organization for the advancement of Canada’s museum community. The CMA works for the recognition, growth, and stability of the sector. Canada’s 2,500 museums and related institutions preserve Canada’s collective memory, shape national identity, and promote tolerance and understanding. For more information, visit the Canadian Museums Association: www.museums.ca

Data from the 2011 Survey of Heritage Institutions in Canada found that attendance at heritage institutions totalled almost 45 million visits, with museums (21.5 million visits) being the most popular.

Spotlight On: British Columbia Museums Association

Founded in 1957 and incorporated in 1966, the British Columbia Museums Association (BCMA) provides a unified voice for the institutions, trustees, professional staff, and volunteers of the BC museum and gallery community. For more information, visit the British Columbia Museums Association: http://museumsassn.bc.ca

British Columbia is home to over 200 museums, including Vancouver’s Museum of Anthropology and Victoria’s Royal BC Museum, both with impressive displays of Aboriginal art and culture. Smaller community museums include the Fraser River Discovery Centre in New Westminster, and the Zeballos Heritage Museum.

Botanical Gardens

A botanical garden is a garden that displays native and non-native plants and trees. It conducts educational, research, and public information programs that enhance public understanding and appreciation of plants, trees, and gardening (Canadensis, 2014).

Canadian botanical gardens host an estimated 4.5 million visitors per year and are important science and educational facilities, providing leadership in plant conservation and public education (Botanic Gardens Convervation International, 2014). British Columbia is home to notable botanical gardens such as Vancouver’s Stanley Park, the Butchart Gardens near Victoria, UBC’s Botanical Garden, and VanDusen Botanical Garden, to name just a few.

Zoos

Zoos all over the world are facing many challenges. A recent article in The Atlantic — whose title poses the question, “Is the Future of Zoos No Zoos at All?” — discusses how the increased use of technology by biologists, such as habitat cameras (nest cams, bear den cams), GPS trackers, and live web feeds of natural behaviours, has transformed the zoo experience into “reality – zoo tv” (Wald, 2014). There is also growing opposition to zoos from organizations such as PETA, who claim that zoo enclosures deprive animals of the opportunity to meet their basic needs and develop relationships (PETA, 2014).

Spotlight On: Canada’s Accredited Zoos and Aquariums

Canada’s Accredited Zoos and Aquariums (CAZA) was founded in 1975. It represents the 33 leading zoological parks and aquariums in Canada and promotes the welfare of, and encourages the advancement and improvement of, related animal exhibits in Canada as humane agencies of recreation, education, conservation, and science. For more information, visit Canada’s Accredited Zoos and Aquariums: www.caza.ca

Canada’s Accredited Zoos and Aquariums (CAZA) work in support of ethical and responsible facilities. Examples of CAZA members in BC include the BC Wildlife Park in Kamloops, the Greater Vancouver Zoo, Kicking Horse Grizzly Bear Refuge near Golden, Shaw Ocean Discovery Centre in Sidney, and the Vancouver Aquarium (Canada’s Accredited Zoos and Aquariums, 2014).

Canadian zoos with high attendance levels include the Toronto Zoo with over 1.3 million guests in 2010 (Toronto Zoo, 2010), and the Vancouver Aquarium with over 1 million visitors in 2013 (Vancouver Aquarium 2013). In 2013, the Calgary Zoo employed almost 300 full- and part-time staff and an additional 99 seasonal employees (Calgary Zoo, 2013).

Amusement and Theme Parks

While cultural and heritage attractions strive to present information based on historic and evolving cultures and facts, amusement parks are attractions that often work to create alternate, fanciful realities. Theme parks have a long history dating back to the 1500s in Europe, and have evolved ever since. Today, it is hard not to try to compare any amusement park destination to Disneyland and Disney World. Opened in 1955 in sunny California, Disneyland set the standard for theme parks. The Pacific National Exhibition (PNE) in Vancouver is considered one of BC’s most recognizable amusement parks and recently celebrated its 100-year anniversary (PNE, 2015).

Canada’s ability to compete with US theme parks is hampered by our climate. With a much shorter summer season, the ability to attract investment in order to sustain large-scale entertainment complexes is limited, as is the market for these attractions. It’s no wonder that in 2011 profitable Canadian amusement parks only saw an average net profit of $73,200, with 34% of firms failing to turn a profit that year. BC has only 22 amusement parks, and more than half of these are considered small, with under 100 employees (Government of Canada, 2014d).

Spotlight On: International Association of Amusement Parks and Attractions

The International Association of Amusement Parks and Attractions (IAAPA) is the largest international trade association for permanently situated amusement facilities worldwide. Dedicated to the preservation and prosperity of the amusement industry, it represents more than 4,300 facility, supplier, and individual members from more than 97 countries, including most amusement parks and attractions in the United States. For more information, visit the International Association of Amusement Parks and Attractions website: www.iaapa.org

Motion Picture and Video Exhibitions

The film industry in Canada, and particularly in BC, has gained international recognition in part through events such as the Toronto International Film Festival, Montreal World Film Festival, and Vancouver International Film Festival. According to the Motion Picture Association — Canada (2013) these festivals attracted an estimated audience of 1.9 million in 2011, as well as over 18,000 industry delegates. Festival operations, visitor spending, and delegate spending combined totalled $163 million that year and generated 2,000 jobs (full-time equivalents).

There are no statistics available on film-induced tourism in Canada, but several notable feature films and television series have been shot here and have drawn loyal fans to production locations. In BC, some of these titles include Reindeer Games and Double Jeopardy (Prince George), Roxanne (Nelson), The Pledge (Fraser Canyon), Battlestar Galactica (Kamloops), The Twilight Saga, Smallville, and Supernatural (Greater Vancouver).

Spotlight On: The Whistler Film Festival

Founded in 2001, the Whistler Film Festival has grown to become one of Canada’s premier events for promoting the development of Western Canada’s film industry and an emerging venue in the international circuit. The festival, held during the first weekend in December, attracts an audience of over 8,200 and more than 500 industry delegates to the ski resort of Whistler, British Columbia, for seminars, special events, and the screening of over 80 independent films from Canada and around the world. For more information, visit the Whistler Film Festival: www.whistlerfilmfestival.com

Spectator Sports and Sport Tourism

Spectator sports and the growing field of sport tourism also contribute significantly to the economy and have become a major part of the tourism industry. According to the Canadian Sport Tourism Alliance (2013), sport tourism is any activity in which people are attracted to a particular location to attend a sport-related event as either a:

- Participant

- Spectator

- Visitor to sport attractions or delegate of sports sector meetings

In 2012, the sport tourism industry in Canada surpassed $5 billion in spending. The domestic market is the largest source of sport tourists, accounting for 84% of all spending, followed by overseas markets (10.8%) and US visitors (5.3% of sport tourism revenues) (Canadian Sport Tourism Alliance, 2014).

Spotlight On: Canadian Sport Tourism Alliance

The Canadian Sport Tourism Alliance (CSTA) was created in 2000 created to market Canada internationally as a preferred sport tourism destination and grow the sport tourism industry in Canada. The purpose of the alliance was to increase Canadian capacity to attract and host sport tourism events. The alliance has over 400 members including 142 municipalities, 200+ national and provincial sport organizations, and a variety of product and service suppliers to the industry. For more information, visit the Canadian Sport Tourism Alliance website: http://canadiansporttourism.com

In British Columbia, sport tourism is supported through the Ministry of Community, Sport and Cultural Development, which invests in event hosting and the ViaSport program (formerly known as Hosting BC). Building on the success of the 2010 Olympic and Paralympic Winter Games, the program has a goal to maintain BC’s profile and reputation as an exceptional major event host. One success story is Kamloops, dubbed the Tournament Capital of Canada, which has made sport tourism a central component of its economy and welcomes over one million visitors to its tournament centre facility each year. And since 1977, the BC Winter and Summer Games have moved around the province, drawing attendees and creating volunteer opportunities for up to 3,200 community members.

Take a Closer Look: The Sport Tourism Guide

The Sport Tourism Guide from Destination BC’s Tourism Business Essentials series covers topics including understanding sport tourism, industry trends, event bidding and hosting, balance sheets, economic impacts, case studies, best practices, and links to additional information. For more information, read the Sport Tourism Guide [PDF]: www.destinationbc.ca/getattachment/Programs/Guides-Workshops-and-Webinars/Guides/Tourism-Business-Essentials-Guides/TBE-Guide-Sport-Tourism-Jun2013.pdf.aspx

Gaming

According to the Canadian Gaming Association, gaming is one of the largest entertainment industries in Canada. It has larger revenues than those generated by magazines and book sales, drinking establishments, spectator sports, movie theatres, and performing arts combined (Canadian Gaming Association, 2011).

In 2011, the association released an economic impact study stating that legalized gaming had nearly tripled in size since 1995, from $6.4 billion to about $15.1 billion.

According to the BC Lottery Corporation, in 2013, the BC gaming industry was made up of:

- 17 casino facilities

- two main horse racetracks

- approximately 4,050 lottery outlets (retailers)

- 28 bingo halls including 18 bingo halls with slot machines (community gaming centres, or CGCs)

Gaming at these facilities and online generated $1.175 billion in net tax revenue to the province of BC, which was reinvested into the heath care system and distributed to communities through a series of grants (BC Lottery Corporation, 2013).

Spotlight on: The BC Lottery Corporation (BCLC)

The BC Lottery Corporation (BCLC) is a provincial Crown corporation that operates under the provincial Gaming Control Act. It is responsible for operating lottery, casino, online, and bingo gaming in BC. For more informatioon, visit the BC Lottery Corporation website: http://corporate.bclc.com

The provincial industry has grown annually since 2006, except in 2010 (slight decrease of about $15 million). The majority of growth was accounted for by the redevelopment/expansion of existing casinos and the introduction of a number of CGCs (Canadian Gaming Association, 2011).

Agritourism, Culinary Tourism, and Wine Tourism

Let’s now have a closer look at the world of farms, food, and wine in the entertainment and tourism industries.

Agritourism

The Canadian Farm Business Management Council defines agritourism as “travel that combines rural settings with products of agricultural operations within a tourism experience that is paid for by visitors” (SOTC, 2011). In other words, rural and natural environments are mixed with agricultural and tourism products and services.

Agritourism products and services can be categorized into three themes:

- Fixed attractions such as historic farms, living farms, museums, food processing facilities, and natural areas

- Events based on an agricultural theme such as conferences, rodeos, agricultural fairs, and food festivals

- Services such as accommodations (B&Bs), tours, retailing (farm produce and products), and activities (fishing, hiking, etc.) that incorporate agricultural products and/or experiences

At a time when farmers are facing increasing costs and the local food movement is growing in popularity, agritourism presents a great opportunity to use farm resources to create experiences for visitors, whether they be for entertainment, education, or as venues for business/meeting events. In BC, examples of agritourism businesses are Salt Spring Island Cheese, Okanagan Lavender Herb Farm near Kelowna, and Amusé Bistro in the Cowichan Valley, where a local monk and mushroom expert forages for local fungi (HelloBC, 2014).

The three primary agricultural regions in BC are:

- The Fraser Valley (outside of Vancouver)

- The Cowichan Valley (on Vancouver Island)

- The Okanagan Valley (in the southern central part of BC)

A number of self-guided circle tours and other experiences are available in these and other areas, including annual festivals and events, such as the Pemberton Slow Food Cycle Sunday, profiled in the Spotlight On below.

Spotlight On: Slow Food Cycle Sunday

The Slow Food Cycle Sunday began in 2005 with the Helmer family farm in Pemberton. The idea is to connect everyday people and city residents to their farmers. Attendees register in advance and then cycle from farm to farm gathering ingredients and enjoying tastings and learning more about farm operations. It’s the opposite of the drive-through fast-food experience, and one that gains popularity every year. For more information, visit Slow Food Cycle Sunday: SlowFoodCycleSunday.com

Culinary Tourism

Culinary tourism refers to “any tourism experience in which one learns about, appreciates, and/or consumes food and drink that reflects the local, regional, or national cuisine, heritage, culture, tradition, or culinary techniques” (Ontario Culinary Tourism Alliance, 2013). The United Nations World Tourism Organization has noted that food tourism is a dynamic and growing segment, and that over one-third of tourism expenditures relate to food (UNWTO, 2012).

Culinary tourism in Canada began to gain traction as a niche in 2002 when the Canadian Tourism Commission highlighted it within the cultural tourism market, and according to a Ryerson University study, the average culinary tourist spends twice the amount of a generic tourist (Grishkewich, 2012).

While an emerging and potentially lucrative market, there is much more to learn about culinary tourists to BC, and Canada. To date more research has profiled an additional sub-segment of culinary tourism, wine tourism, which we’ll explore next.

Wine Tourism

The North American Industrial Classification System (NAICS) defines wine tourism as the “tasting, consumption, or purchase of wine, often at or near the source, such as wineries.” It also includes an educational aspect and festivals focusing on the production of wine (Agriculture and Agri-food Canada, 2014).

There are more than 200 wineries in BC, ranging from small family-run vineyards to large estate operations. In 2011, BC’s wine industry generated $1.43 billion in business revenue, and either directly or indirectly supported over 10,000 full-time jobs (Frank, Rimerman + Co, 2013).

Specific to tourism, wineries across BC attracted over 800,000 visitors in 2011, generating $1.63 million, more than 10% of total provincial wine revenues. Wine tourism accounted for over 2,000 wine-related jobs that year, approximately 20% of total wine industry jobs (Frank, Rimmerman + Co, 2013).

Take a Closer Look: Wine Tourism Product Report

For more information on the wine sector in British Columbia, read this 2009 report that speaks to market profiles, industry makeup and other important information: Wine Tourism Product Report, 2009 [PDF]:

http://www.destinationbc.ca/getattachment/Research/Research-by-Activity/Land-based/Wine_Sector_Profile.pdf.aspx

According to the 2006 Travel Activities and Motivations Survey (TAMS), 3.3 million Canadians and 30 million Americans participated in wine tourism in 2004/2005, with BC receiving 45% of the Canadian visitors, and just over 9% of the American guests. These visitors earned 40% higher incomes than generic visitors, were well-educated, evenly split between men and women, and represented a slightly older demographic (Destination BC, 2009).

While more recent data is not currently available on this still-developing sector, industry experts agree that agritourism, culinary tourism, and wine tourism will continue to attract lucrative visitors and play a growing role in BC’s tourism economy.

Trends and Issues

So far in this chapter, we’ve looked at entertainment experiences from wine to gambling, from farm-fresh foods to museums and galleries, and at many things in between. But the entertainment sector doesn’t exist in a perfect world. Now let’s examine some of the trends and issues in the sector today. Festivals, events, and other entertainment experiences can have significant positive, and negative, impacts on communities and guests.

Impacts of Entertainment

Each type of festival, event, or attraction will have an impact on the host community and guests. Table 6.2 lists some of the positive impacts that can be built upon and celebrated. It also lists some of the potential negative impacts event coordinators should strive to limit.

| [Skip Table] | ||

| Type of Impact | Positive Impacts | Negative Impacts |

|---|---|---|

| Social and Cultural |

|

|

| Physical and Environmental |

|

|

| Political |

|

|

| Tourist and Economic |

|

|

Technology

The role of technology is shifting the guest experience from the physical to the virtual. Online gambling, virtual exhibits, and live streaming animal habitat cams are just a few of the new ways that visitors can be entertained, often without having to visit the destination. As this type of experience continues to thrive, the sector must constantly adapt to capture revenues and attention.

Conclusion

Across Canada and within BC the range of activities to entertain and delight travellers runs from authentic explorations of cultural phenomena to pure amusement. Those working in the entertainment tourism sector know that providing a friendly, welcoming experience is a key component in sustaining any tourism destination. Whether through festivals, events, attractions, or new virtual components, the tourism industry relies on entertainment to complete packages and ensure guests, whether business or leisure travellers, increase their spending and enjoyment.

Thus far we’ve explored the key sectors of transportation, accommodation, food and beverage, and recreation and entertainment. The final sector, travel services, brings these all together, and is explored in more detail in Chapter 7.

Key Terms

- Agritourism: tourism experiences that highlight rural destinations and prominently feature agricultural operations

- Art museums: museums that collect historical and modern works of art for educational purposes and to preserve them for future generations

- Botanical garden: a garden that displays native and/or non-native plants and trees, often running educational programming

- British Columbia Lottery Corporation (BCLC): the rown corporation responsible for operating casinos, lotteries, bingo halls, and online gaming in the province of BC

- Business Events Industry Coalition of Canada (BEICC): an advocacy group for the meetings and events industry in Canada

- Canadian Sport Tourism Alliance (CSTA): created in 2000, an industry organization funded by the Canadian Tourism Commission to increase Canadian capacity to attract and host sport tourism events

- Community gaming centres (CGCs): small-scale gaming establishments, typically in the form of bingo halls

- Conferences: business events that have specific themes and are held for smaller, focused groups

- Conventions: business events that generally have very large attendance, are held annually in different locations each year, and usually require a bidding process

- Culinary tourism: tourism experiences where the key focus is on local and regional food and drink, often highlighting the heritage of products involved and techniques associated with their production

- Cultural/heritage tourism: when tourists travel to a specific destination in order to participate in a cultural or heritage-related event

- Entertainment: (as it relates to tourism) includes attending festivals, events, fairs, spectator sports, zoos, botanical gardens, historic sites, cultural venues, attractions, museums, and galleries

- Event: a happening at a given place and time, usually of some importance, celebrating or commemorating a special occasion; can include mega-events, special events, hallmark events, festivals, and local community events

- Festival: a public event that features multiple activities in celebration of a culture, an anniversary or historical date, art form, or product (food, timber, etc.)

- Incentive travel: a global management tool that uses an exceptional travel experience to motivate and/or recognize participants for increased levels of performance in support of organizational goals

- International Festivals and Events Association (IFEA): organization that supports professionals who produce and support celebrations for the benefit of their respective communities

- Meetings, conventions, and incentive travel (MCIT): all special events with programming aimed at a business audience

- Meeting Professionals International (MPI): a membership-based professional development organization for meeting and event planners

- Public galleries: art galleries that do not generally collect or conserve works of art; rather, they focus on exhibitions of contemporary works as well as on programs of lectures, publications, and other events

- Society for Incentive Travel Excellence (SITE): a global network of professionals dedicated to the recognition and development of motivational incentives and performance improvement

- Sport tourism: any activity in which people are attracted to a particular location as a participant, spectator, or visitor to sport attractions, or as an attendee of sport-related business meetings

- Tourist attractions: places of interest that pull visitors to a destination; open to the public for entertainment or education

- Trade shows/trade fairs: can be stand-alone events, or adjoin a convention or conference and allow a range of vendors to showcase their products and services either to other businesses or to consumers

- Wine tourism: tourism experiences where exploration, consumption, and purchase of wine are key components

Exercises

- Review the categories of events. What types of events have you ever attended in person? What types of events are held in your community? Try to list at least one for each category.

- Should the government (municipal, provincial, federal) support festivals and events? Why or why not?

- Aside from convention centres, where else can meetings, conventions, and conferences be held? Use your own creative ideas to list at least five other venues.

- What are some of the main sources of revenue for attractions (both mainstream and cultural/heritage attractions)? What are the main expenses?

- Should private sector investors receive government funding for tourism entertainment facilities? Should they be required to contribute their revenues to the community? Why or why not?

- Name a cultural or heritage attraction in your community. Where does its revenue come from? What are its major expenses? Who are its target markets? Based on this information, make three key recommendations for sustaining its business.

- Do you agree with certain animal rights groups that zoos should be shut down? Why or why not?

Case Study: Merridale Estate Cidery

Purchased by husband and wife team Janet Docherty and Rick Pipes in 2000, Merridale Estate Cidery is located in the Cowichan Valley on Vancouver Island. The cidery itself was established by the previous owner in 1990 who planted apple trees in the location, which is considered ideal by many for its terrain and climate.

With the purchase of the cidery, Janet and Rick undertook an extensive renovation in order to transform the facility into an agritourism attraction. They expanded the cellar and tasting rooms and created the Cider House in 2003 from which they began running tours and tastings. From there they added:

- The Farmhouse Store with retail sales of their cider product, local agriculture products, and BC arts and crafts

- The Bistro and Orchard Cookhouse, two distinct food and beverage operations

- The Brick Oven Bakery (producing artisanal baked goods in its on-site brick oven)

- Yurts (two cabin-style tents) for onsite accommodation

The cidery is now a destination for special events such as weddings. It also runs an InCider Club for frequent purchasers of its products.

Visit the Merridale website at www.merridalecider.com and answer the following questions:

- What is Merridale’s core business?

- Who are its customers?

- Merridale comprises food and beverage, retail, accommodations, and is an attraction. How would you classify it as a tourism operation?

- Is Merridale a seasonal operation? What would you consider to be its peak season? How has it extended revenue-earning opportunities?

- Merridale’s slogan is “Apples Expressed.” Does this tagline capture its essence? Why or why not?

- Consider Merridale’s products, experiences, and markets. What partners should the cidery work with, either globally or locally, to attract business? Name at least three.

- Do you think Merridale should add components, or eliminate components, from its business? Explain your answer.

References

Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada. (2014). The Canadian wine industry. Retrieved from www.agr.gc.ca/eng/industry-markets-and-trade/statistics-and-market-information/by-product-sector/processed-food-and-beverages/the-canadian-wine-industry/?id=1172244915663

Botanic Gardens Conservation International. (2014). Welcome to BGCI Canada. Retrieved from www.bgci.org/canada

British Columbia Lottery Corporation. (2014). BCLC 2013-14 annual report. Retrieved from http://issuu.com/bclc-onlinelibrary/docs/bclc_2013-14_annual_report?e=1760950/8584471

Business Events Industry Coalition of Canada. (2014). Business events are big business. Retrieved from http://beicc.com/ceis/

Calgary Zoo. (2013). Calgary Zoo 2013 annual report. [PDF] Retrieved from www.calgaryzoo.com/sites/default/files/pdf/2013-CGYZoo-AnnualReport_WEB.pdf

CAMDO. (2014). Canadian Art Museum Directors Organization blog. Retrieved from www.camdo.ca/blog/?page_id=458

Canada’s Accredited Zoos and Aquariums. (2014). About us. Retrieved from www.caza.ca

Canadensis.(2014). FAQ. Retrieved from www.canadensisgarden.ca/f-a-q/

Canadian Gaming Association. (2011, October 19). Canadian gaming industry matures into one of the largest entertainment industries in the country. Retrieved from www.canadiangaming.ca/news-a-articles/95-canadian-gaming-industry-matures-into-one-of-the-largest-entertainment-industries-in-the-country-the-cgas-economic-impact-study-finds.html

Canadian Sport Tourism Alliance. (2013). Value of sport tourism. Retrieved from www.canadiansporttourism.com/value-sport-tourism.html

Canadian Sport Tourism Alliance. (2014). Sport tourism: Full steam ahead! Retrieved from http://canadiansporttourism.com/news/sport-tourism-full-steam-ahead.html

Canadian Tourism Commission. (1998). Canada’s tourist attractions: A statistical snapshot 1995-96.

Colston, K. (2014, April 24). Non-traditional event venues – Endless entertainment. Retrieved from http://helloendless.com/non-traditional-event-venues/

Destination BC. (2009, October). Wine tourism insight. [PDF] Retrieved from www.destinationbc.ca/getattachment/Research/Research-by-Activity/Land-based/Wine_Sector_Profile.pdf.aspx

Enigma Research Consultants. (2009). The economic impact of Canada’s largest events and festivals [PDF]. Retrieved from http://fame-feem.ca/wp-content/themes/sands/downloads/2009%20Economic%20Impact%20of%20Canada’s%20Largest%20Festivals%20and%20Events.pdf

Frank, Rimerman + Co. LLP. (2013). The economic impact of the wine and grape industry in Canada 2011. [PDF] Retrieved from http://engage.gov.bc.ca/liquorpolicyreview/files/2013/11/Canadian-Vintners-Association.pdf

Getz, D. (1997). Event management and event tourism. New York, NY: Cognizant Communications, p.6.

Goldblatt, J. (2001). The international dictionary of event management (2nd ed.). New York, NY: John Wiley & Sons, p. 78.

Government of Canada. (2014a). Funds awarded – Major events. Retrieved from www.pch.gc.ca/eng/1389635366164

Government of Canada. (2014b). Survey of heritage institutions: 2011. [PDF] Canadian Heritage. Retrieved from

www.pch.gc.ca/DAMAssetPub/DAM-verEval-audEval/STAGING/texte-text/2011_Heritage_Institutions_1414680089816_eng.pdf?WT.contentAuthority=6.0

Government of Canada. (2014c). Performing arts, operating statistics. Retrieved from www.statcan.gc.ca/tables-tableaux/sum-som/l01/cst01/arts73a-eng.htm

Government of Canada. (2014d). Amusement and recreation, summary statistics. Retrieved from www.statcan.gc.ca/tables-tableaux/sum-som/l01/cst01/arts60a-eng.htm

Grishkewich, Cheryl. (2012, January 12). Culinary tourists: Recipe for economic development success. Retrieved from: https://ontarioculinary.com/cheryls-tasty-tid-bits/

HelloBC. (2014, October 20). Down on the farm: Agritourism in BC. Retrieved from http://travelmedia.hellobc.com/stories/down-on-the-farm–agritourism-in-bc.aspx

LinkBC. (2012). Cultural & heritage tourism: A handbook for community champions. [PDF] Retrieved from www.linkbc.ca/siteFiles/85/files/CHT_WEB.pdf

Motion Picture Association – Canada. (2013). Issues and positions. [PDF] Retrieved from www.mpa-canada.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/03/MPA-Canada_Nordicity-Report_July-2013_English.pdf

Ontario Culinary Tourism Alliance. (2013). Culinary tourism: A definition. Retrieved from: https://ontarioculinary.com/resources/culinary-tourism-101/

Pacific National Exhibition. (n.d.). About us. Retrieved from http://www.pne.ca/aboutus/index.html

PETA – People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals. (2014). Our views. Retrieved from www.peta.org/about-peta/why-peta/zoos/#ixzz3LiYfeI6C)

Society of Incentive Travel Excellence. (2014). History. Retrieved from www.siteglobal.com/p/cm/ld/fid=109

SOTC – Southwest Ontario Tourism Corporation. (2011). What is agritourism? Retrieved from www.osw-agritourismtoolkit.com/Agribusiness/What-is-Agritourism

Swarbrooke, J. (2002). The development & management of visitor attractions, 2nd ed. Oxford, UK: Butterworth Heinemann.

Toronto Zoo. (2010). Toronto Zoo 2010 annual report [PDF]. Retrieved from www.torontozoo.com/pdfs/Toronto%20Zoo%202010%20Annual%20Report.pdf

United Nations World Tourism Organization. (2012). Global report on food tourism. Retrieved from www.silkroad.unwto.org/publication/unwto-am-report-vol-4-global-report-food-tourism

Vancouver Aquarium. (2013). Vancouver Aquarium annual report 2013 [PDF]. Retrieved from: www.vanaqua.org/annualreport2013/assets/dist/pdfs/annualreport2013.pdf

Wald, C. (2014, November). Is the future of zoos no zoos at all? The Atlantic. Retrieved from www.theatlantic.com/technology/archive/2014/11/is-the-future-of-zoos-no-zoos-at-all/383070/

Attributions

Figure 6.1 Labyrinth of Light by Tavis Ford is used under a CC-BY 2.0 license.

Figure 6.2 Cornucopia :: Whistler’s Celebration of Wine & Food by Shinsuke Ikegame is used under a CC-BY 2.0 license.

Figure 6.3 Pan Pacific Vancouver and the Vancouver Convention Center by Pan Pacific is used under a CC-BY 2.0 license.

Figure 6.4 Pioneer by J Scott is used under a CC-BY-SA 2.0 license.

Figure 6.5 yoshiko by Raul Pacheco-Vega is used under a CC-BY-NC-ND 2.0 license.

Figure 6.6 Swingers and Spinners | The PNE Fairgrounds by Rikki/Julius Reque is used under a CC-BY-NC-SA 2.0 license.

Figure 6.7 Edgewater Casino by colink is used under a CC-BY-SA 2.0 license.

Figure 6.8 Saturna Vineyards by David Stanley is used under a CC-BY 2.0 license.