Chapter 4. Food and Beverage Services

Peter Briscoe and Griff Tripp

Learning Objectives

- Describe the origins and significance of the food and beverage sector

- Relate the importance of the sector to the Canadian economy

- Explain the various types of food and beverage providers

- Discuss differing needs and desires of residents and visitors in selecting a food and beverage provider

- Examine factors that contribute to the profitability of food and beverage operations

- Discuss key issues and trends in the sector including government influence, health and safety, human resources, and technology

Overview

According to Statistics Canada, the food and beverage sector comprises "establishments primarily engaged in preparing meals, snacks and beverages, to customer order, for immediate consumption on and off the premises" (Government of Canada, 2012). This sector is commonly known to tourism professionals by its initials as F&B.

The food and beverage sector grew out of simple origins: as people travelled from their homes, going about their business, they often had a need or desire to eat or drink. Others were encouraged to meet this demand by supplying food and drink. As the interests of the public became more diverse, so too did the offerings of the food and beverage sector.

In 2014, Canadian food and beverage businesses accounted for 1.1 million employees and more than 88,000 locations across the country with an estimated $71 billion in sales, representing around 4% of the country's overall economic activity. Many students are familiar with the sector through their workplace, because Canada's restaurants provide one in every five youth jobs in the country -- with 22% of Canadians starting their career in a restaurant or foodservice business. Furthermore, going out to a restaurant is the number one preferred activity for spending time with family and friends (Restaurants Canada, 2014a).

Food and Beverage Sector Performance

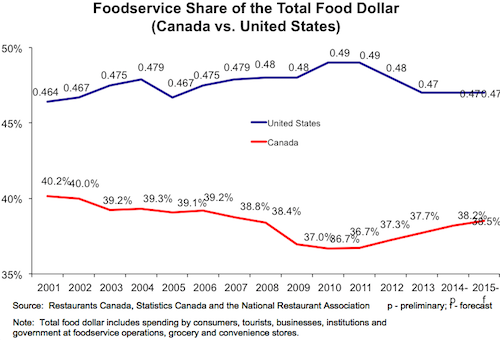

Look at Figure 4.1, which illustrates the percentage of total food dollars spent in restaurants in Canada and the United States over several years. As you can see, Americans spend significantly more of their total food dollars in foodservice establishments than in grocery stores, and in Canada we spend more of our total food dollars in the grocery store than we do in foodservice operations. It's worth noting that Americans do not have an equivalent federal sales tax on meals comparable to our GST on foodservice sales, although there does exist in some states a sales tax on meals and alcoholic beverages (State Sales Tax Rates, 2015). This, combined with a larger population, cheaper food distribution costs, and other factors can often mean that it's less expensive to dine out in the United States than in Canada.

For a perspective on how sales are distributed across the country by province, and how different foodservice operations perform in terms of revenue (sales dollars collected from guests), look at Tables 4.1 and 4.2.

| [Skip Table] | ||||

| Province | Foodservice Units | Average Volume/Unit ($) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Chain Share (%) | Independent Share (%) | ||

| Newfoundland and Labrador | 1,127 | 44 | 56 | 715,976 |

| Prince Edward Island | 369 | 35 | 65 | 549,428 |

| Nova Scotia | 2,089 | 40 | 60 | 637,237 |

| New Brunswick | 1,701 | 48 | 52 | 579,576 |

| Quebec | 21,865 | 31 | 69 | 488,712 |

| Ontario | 33,628 | 45 | 55 | 623,862 |

| Manitoba | 2,448 | 41 | 59 | 657,245 |

| Saskatchewan | 2,330 | 43 | 57 | 744,322 |

| Alberta | 9,858 | 47 | 53 | 828,860 |

| British Columbia | 13,214 | 33 | 67 | 627,599 |

| Canada | 88,795 | 40 | 60 | 619,013 |

| Data source: Statistics Canada, 2013 | ||||

| [Skip Table] | ||||

| Province | Sales Growth | Sales | Pre-tax Profit Margin (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2013-14 Forecast (%) | 2012-13 (%) | 2013 ($ millions) | ||

| Newfoundland and Labrador | 2.7 | 9.2 | 806.9 | 6.7 |

| Prince Edward Island | 1.6 | 4.4 | 202.7 | 5.7 |

| Nova Scotia | 3.8 | 0.7 | 1,330.9 | 5.2 |

| New Brunswick | 2.1 | 0.3 | 985.6 | 5.2 |

| Quebec | 3.8 | 2.7 | 10,685.4 | 3.9 |

| Ontario | 4.1 | 4.2 | 20,979.2 | 2.8 |

| Manitoba | 4.6 | 6.1 | 1,608.6 | 7.9 |

| Saskatchewan | 4.7 | 7.0 | 1,733.9 | 7.0 |

| Alberta | 5.4 | 6.4 | 8,170.5 | 7.1 |

| British Columbia | 3.7 | 6.1 | 8,292.8 | 3.4 |

| Canada | 4.2 | 4.6 | 54,965.3 | 4.2 |

| Data source: Statistics Canada, 2013 | ||||

Table 4.1 shows that the independents in BC have a much larger share of the total number of units compared with chains than any other province except Quebec. In terms of sales (Table 4.2), Ontario is the leader with almost $21 billion. Quebec, BC, and Alberta each earned $8 to $10 billion, and the other provinces had sales of less than $2 billion apiece. While BC and Alberta are almost even in total sales, BC has a third more units (restaurants), leading to lower average sales per unit.

Foodservice sales in Alberta rose by a solid 6.4% in 2013. Alberta boasts the highest average unit volume at $828,860 per year, more than $200,000 over the national average due to greater disposable income and no provincial sales tax on meals. In BC, the end of the HST (harmonized sales tax) and improved economic growth lifted total foodservice sales by a healthy 6.1% for the strongest annual growth since 2006 (Restaurants Canada, 2014a).

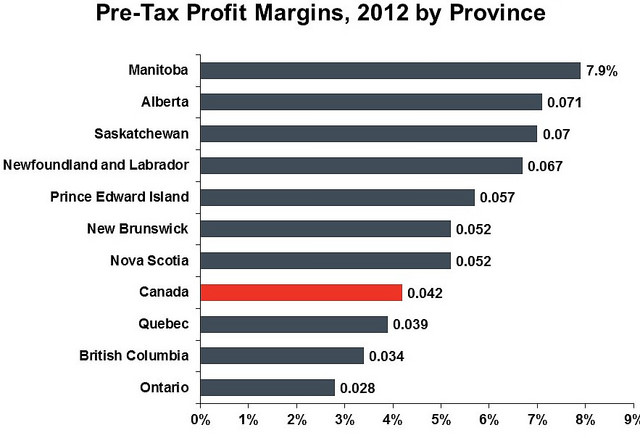

Now let's take a quick look at which provinces have the most profitable foodservice operations.

Figure 4.2 indicates the profit margins per province. Profit is the amount left when expenses (including corporate income tax) are subtracted from sales revenue. A higher profit margin means that a greater percentage of sales is retained by the business owner, and a lower percentage is lost to operating and other costs.

The provincial variations in total sales and profit margins are due to several factors including:

- Relative level of economic activity

- Minimum wage levels

- Provincial sales taxes

- Cultural differences

- Weather

- Municipal taxes

- Percentage of market held by chains versus independents

- Number of units (restaurants)

- Density of units relative to local population

- Number of tourists or business travellers

Now that we have a sense of the relative performance of F&B operations by province, and some influences on success, let's delve a little deeper into the sector.

Types of Food and Beverage Providers

While there are many ways to analyze the sector, in this chapter, we take a market-based, business-operation approach based on the overall Canadian market share from the Restaurants Canada Market Review and Forecast (Restaurants Canada, 2014b). The following sections explore the types of foodservice operations in Canada.

There are two key distinctions: commercial foodservice, which comprises operations whose primary business is food and beverage, and non-commercial foodservice establishments where food and beverages are served, but are not the primary business.

Let's start with the largest segment of F&B operations, the commercial sector.

Commercial Operators

Commercial operators make up the largest segment of F&B in Canada with just over 80% market share (Restaurants Canada, 2014b). It is made up of quick-service restaurants, full-service restaurants, catering, and drinking establishments. Let's look at each of these in more detail.

Quick-Service Restaurants

Formerly known as fast-food restaurants, quick-service restaurants, or QSRs, make up 35.4% of total food sales in Canada (Restaurants Canada, 2014b). This prominent portion of the food sector generally caters to both residents and visitors, and is represented in areas that are conveniently accessed by both. Brands, chains, and franchises dominate the QSR landscape. While the sector has made steps to move away from the traditional fast-food image and style of service, it is still dominated by both fast food and food fast; in other words, food that is prepared and purchased quickly, and generally consumed quickly.

Take a Closer Look: The First McDonald's In Canada

The first McDonald's restaurant in Canada opened in Richmond, BC, in 1967. Located on No. 3 Road, it featured a sleek almost space-age design. To see a picture of the location, visit McDonald's: Then and Now: www.richmond.ca/cityhall/archives/exhibits/thenandnow/then_now_set_7.htm

Convenience and familiarity is key in this sector. Examples of QSRs include:

- Drive-through locations

- Stand-alone locations

- Locations within retail stores

- Kiosk locations

- High-traffic areas, such as major highways or commuter routes

Full-Service Restaurants

With 35% of the market share (Restaurants Canada, 2014b), full-service restaurants are perhaps the most fluid of the F&B operation types, adjusting and changing to the demands of the marketplace. Consumer expectations are higher here than with QSRs (Parsa, Lord, Putrevu, & Kreeger, 2015). The menus offered are varied, but in general reflect the image of the restaurant or consumer’s desired experience. Major segments include fine dining, family/casual, ethnic, and upscale casual.

Fine dining restaurants are characterized by highly trained chefs preparing complex food items, exquisitely presented. Meals are brought to the table by experienced servers with sound food and beverage knowledge in an upscale atmosphere with table linens, fine china, crystal stemware, and silver-plate cutlery. The table is often embellished with fresh flowers and candles. In these businesses, the average cheque, which is the total sales divided by number of guests served, is quite high (often reviewed with the cost symbols of three or four dollar signs- $ $ $ or $ $ $ $).

Bishop's in Vancouver is one of BC's best known and longest operating fine dining restaurants. Since opening in 1985, this 45-seat restaurant has served heads of state including Bill Clinton and Boris Yeltsin, and has won awards including the Best of Vancouver. John Bishop was awarded the Governor General's Award in 2010 (Georgia Straight, 2015).

Family/casual restaurants are characterized by being open for all three meal periods. These operations offer affordable menu items that span a variety of customer tastes. They also have the operational flexibility in menu and restaurant layout to welcome large groups of diners. An analysis of menus in family/casual restaurants reveals a high degree of operational techniques such as menu item cross-utilization, where a few key ingredients are repurposed in several ways. Both chain and independent restaurant operators flourish in this sector. Popular chain examples in BC include White Spot, Ricky’s All Day Grill, Boston Pizza, and The Old Spaghetti Factory. Independents include the Red Wagon Café in Vancouver, the Bon Voyage Restaurant near Prince George, and John’s Place in Victoria.

Ethnic restaurants typically reflect the owner’s cultural identity. While these restaurants are popular with many markets, they are often particularly of interest to visitors and new immigrants looking for a specific environment and other people with whom they have a shared culture. Food is often the medium for this sense of belonging (Koc & Welsh, 2001; Laroche, Kim, Tomiuk, & Belisle, 2005).

The growth and changing nature of this sector reflects the acceptance of various ethnic foods within our communities. Ethnic restaurants generally evolve along two routes: toward remaining authentic to the cuisine of the country of origin, or toward larger market acceptance through modifying menu items (Mak, Lumbers, Eves, & Chang, 2012).

Upscale casual restaurants emerged in the 1970s, evolving out of a change in social norms. Consumers began to want the experience of a fun social evening at a restaurant with good value (but not cheap), in contrast to the perceived stuffiness of fine dining at that time. These restaurants are typically dinner houses, but they may open for lunch or brunch depending on location. Examples in BC include the Keg, Earls, Cactus Club, Brown's Social House, and Joey Restaurants.

Catering and Banqueting

Catering makes up only 6.8% of the total share of F&B in Canada (Restaurants Canada, 2014b) and comprises food served by catering companies at banquets and special events at a diverse set of venues. Note that banqueting pertains to catered food served on premise, while catering typically refers to off-premise service. At a catered event, customers typically eat at the same time, as opposed to restaurant customers who are served individually or in small groups.

Catering businesses (whether on-site or at special locations) are challenged by the episodic nature of events, and the issues of food handling and food safety with large groups. Catering businesses include:

- Catering companies

- Conference centres

- Conference hotels

- Wedding venues

- Festival food coordinators

Spotlight On: Diner en Blanc

An interesting public event with a dining focus is Diner en Blanc, which is held in cities around the globe including Vancouver and Victoria. Diners wear all white and bring their table, chair, and place settings with them to a secret location announced only hours before. Participants have the option to bring their own food or purchase a catered meal. Alcoholic beverages are also available for purchase on site. For more information, visit the Diner en Blanc website: http://vancouver.dinerenblanc.info/media

While beverages make up part of almost every dining experience, some establishments are founded on beverage sales. Let's look at these operations next.

Drinking

With 3.5% market share (Restaurants Canada, 2014b), the drinking establishment sector comprises bars, wine bars, cabarets, nightclubs, and pubs. In British Columbia, all businesses and premises selling alcohol must adhere to the BC Liquor Control and Licensing Act. At the time this chapter was written, significant changes were taking place in the regulations governing drinking establishments, but some general conditions have remained stable.

In BC, liquor licences are divided into liquor primary and food primary. As the name suggests, a liquor primary licence is needed to operate a business that is in the primary business of selling alcohol. Most pubs, nightclubs, and cabarets fall into this category. A food primary licence is required for an operation whose primary business is serving food. Some operations, such as pubs, will hold a liquor primary licence even though they serve a significant volume of food. In this case, the licence allows for diverse patronage.

One noteworthy change to the licensing of pubs in BC is that children are permitted in them if they are accompanied and attended by responsible adults. While not universally adopted by pubs to date, this change in legislation is an example of the fluctuating social norms to which the sector must respond.

Together the commercial ventures of QSRs, full-service restaurants, catering functions, and drinking establishments make up just over 80% of the market share. Now let's look at the other 20% of businesses, which fall under the non-commercial umbrella.

Non-Commercial

The following non-commercial entities earn just under 20% share of the foodservice earnings in Canada (Restaurants Canada, 2014b). While these make up a smaller share of the market, there are some advantages inherent in these business models. Non-commercial operations cater predominantly to consumers with limited selection or choice given their occupation or location. This type of consumer is often referred to as a captured patron. In a tourism capacity such as in airports or on cruise ships, the accepted price point for these patrons is often higher for a given product, increasing profit margins.

Institutional

Often run under a predetermined contract, this sector includes:

- Hospitals

- Universities, colleges, and other educational institutions

- Prisons and other detention facilities

- Corporate staff cafeterias

- Cruise ships

- Airports and other transportation terminals and operations

Accommodation Foodservice

These include hotel restaurants and bars, room service, and self-serve dining operations (such as a breakfast room). Hotel restaurants are usually open to the public and reliant on this public patronage in addition to business from hotel guests. Collaborations between hotel chains and restaurant chains have seen reliable pairing of hotels and restaurants, such as the combination of Sandman Hotels and Moxie’s Grill and Bar.

Vending and Automated Foodservices

While not generally viewed as part of the food and beverage sector, automated and vending services do account for significant sales for both small and large foodservice and accommodation providers. Vending machines are located in motels, hotels, transportation terminals, sporting venues, or just about any location that will allow for the opportunity for an impulse or convenient purchase.

Business Performance for Types of Food and Beverage Operators

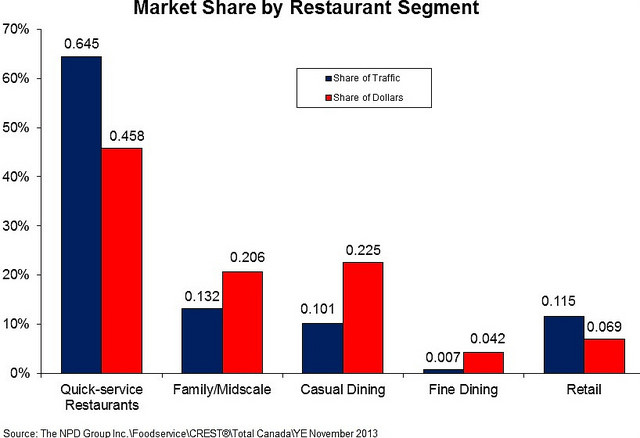

As mentioned, the commercial sector comprises the majority of dollars earned. Figure 4.9 illustrates the difference between share of traffic and share of dollars for each subsector. We know that QSRs are much more economical and generally much busier than full-service restaurants. How does that traffic and low prices translate into market share for the different segments?

Figure 4.9 shows that QSRs attract two-thirds of all the traffic, while earning less than half of the total dollars. Family/midscale and casual dining each attract half the dollars of QSR, but they do that from much lower shares of the traffic. Meanwhile fine dining is patronized by less than 1% of the total restaurant traffic, but earns 4.2% of the dollars. The growing force of convenience stores, department stores, and other retail establishments obtain a respectable 11.5% of traffic and 10.6% of the restaurant dollar.

As you can see, while QSRs attract the greatest number of guests, the ratio of dollars earned per transaction is significantly less than that of the fine dining sector. This makes sense, of course, because the typical QSR earns relatively little per guest but attracts hundreds of customers, while a fine dining restaurant charges high prices and serves a select few guests each day.

Sales Per Segment

| [Skip Table] | |||||

| Type of Restaurant | 2012 Final ($ millions) | Segment Market Share (%) | 2013 Preliminary ($ millions) | Segment Market Share (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| COMMERCIAL | QSR | 23,139.7 | 35.4 | 24,114.5 | 35.4 |

| Full-service | 22,631.1 | 34.7 | 23,847.3 | 35.0 | |

| Caterers | 4,443.6 | 6.8 | 4,644.9 | 6.8 | |

| Drinking places | 2,355.6 | 3.6 | 2,358.6 | 3.5 | |

| Total Commercial | 52,570.1 | 80.5 | 54,965.3 | 80.7 | |

| NON-COMMERCIAL | Accommodation | 5,456 | 8.4 | 5,647.0 | 8.3 |

| Institutional | 3,668.6 | 5.6 | 3,898.5 | 5.7 | |

| Retail | 1,234.3 | 1.9 | 1,199.4 | 1.8 | |

| Other | 2,362 | 3.6 | 2,416.3 | 3.5 | |

| Total Non-Commercial | 12,720.9 | 19.5 | 13,161.3 | 19.3 | |

| Data source: Restaurants Canada, 2013 | |||||

The sales revenues for the various segments are shown in Table 4.3. Note that QSRs and full-service restaurants are almost equal in their sales and almost completely dwarf the other commercial sectors of caterers and drinking places. It is also noteworthy that the commercial components have four times the sales volume of the non-commercial components.

Types of Food and Beverage Customers

Now that we've classified the sector based on business type and looked at relative performance, let's look at F&B from another perspective: customer type. The first way to classify customers is to divide them into two key markets: residents and visitors.

The first of these, the resident group, can be further divided based on their purpose for visiting an F&B operator. For one group, food or drink is the primary purpose for the visit. For example, think of a group of friends getting together at a local restaurant to experience their signature sandwich. For another group, food and drink is the secondary purpose, added spontaneously or as an ancillary activity. For example, think of time-crunched parents whisking their kids through a drive-through on their way from one after-school activity to the next. Here the food and beverage providers offer an expedient way to access a meal.

Foodservice providers also service the visitor market, which presents unique challenges as guests will bring with them the tastes and eating habits of their home country or region. Most establishments generally follow one of two directions. One is to cater completely to visitors from the day the doors open, with an operational and market focus on tourists. The other is to cater primarily to residents.

Sometimes a local foodservice provider can continue to cater to the resident market over time. In other cases, often because of financial pressures, the business shifts its focus away from the residents to better cater to visitors’ tastes. These changes, when they do occur, generally happen over time and can lead to questions of authenticity of the local offerings (Smart, 2003; Heroux, 2002; Mak, Lumbers, Eves, & Chang, 2012).

Take a Closer Look: The Science of Addictive Food

For some time, one secret recipe for success in the food sector, particularly the fast-food portion of the sector, was simple: salt, sugar, and fat -- and lots of it. There is a science behind these additives and why consumers keep coming back to satisfy their cravings. To view a CBC special on the science of addictive food, visitThe science of Addictive Food: www.youtube.com/watch?v=4cpdb78pWl4

It is clear that the food and beverage sector must remain responsive to consumers’ needs and desires. This is made evident by the emergence of health-concious eating in North America over the last two decades. The influence of books such as Fast Food Nation (Schlosser, 2012) and documentaries such as Super Size Me have created mainstream awareness about what goes into our food and our bodies. As many developed nations, including Canada, struggle with health-care concerns including hypertension, diabetes, and obesity, food operators are taking note and developing new health-conscious menus. Programs like BC's Informed Dining initiative are helping consumers understand their options (see the Spotlight On below).

Spotlight On: Informed Dining

The Informed Dining program was created by Healthy Families BC to help consumers gain a better understanding of the ingredients in their food and their role in daily healthy eating habits and guidelines. For more information, visit the Informed Dining webpage: www.healthyfamiliesbc.ca/home/informed-dining

This awareness, coupled with an increasing interest and desire for more authentic foods produced without using herbicides and pesticides, free of genetically modified ingredients, and even free of carbohydrates or gluten, has placed pressure on the sector to respond, and many have (Frash, DiPietro, & Smith, 2014). Consumers are more aware of the plight of farmers and producers from faraway places and the support for fair trade practices. At the same time, there is a heightened desire for more locally grown products, and a general awareness of nutrition and the quality of products that are harvested in season and closer to home.

Take a Closer Look: Cittaslow Designation for Cowichan Bay

The community of Cowichan Bay on Vancouver Island was awarded the Cittaslow Designation, which helps acknowledge its focus on sustainable practices and local food harvesting best practice. For more information on the designation and community efforts, watch the video, Cittaslow Cowichan Bay: www.youtube.com/watch?v=_JQ-Cnh-v5Q

Consumer consciousness regarding the source and distribution of food has created a movement that champions sustainable and locally grown foods. While this trend does have its extremes, it is founded on the premise that eating food that has been produced nearby leads to better food quality, sustainable food production processes, and increased enjoyment. This has led to a number of restaurants that incorporate these concepts in their menu planning and marketing.

In addition to this trend toward "conscious consumerism" (LinkBC, 2014, p.4), F&B professionals must be highly aware of the importance of special diets including gluten-free, low-carb, and other dietary restrictions (LinkBC, 2014).

All of these influences are continuously shaping the food and beverage sector. Before we explore additional trends and issues in the sector, let's review the core considerations for profitability in foodservice operations.

Profitability

While many factors influence the profitability of foodservice operations, key considerations include type of business, location, cost control and profit margin, sales and marketing strategies, and human resources management. We've already examined the different types of operation, and their relative profit margins. Let's look at the other profitability considerations in more detail.

Location

The selection of the correct location for a restaurant is often cited as the most critical factor in an operation's success (or failure) in terms of profitability. Prior to opening, site analysis is required to determine the amount of traffic (foot traffic and vehicle traffic), proximity to competing businesses, visibility to patrons, accessibility, and presence (or absence) of desired patrons (Ontario Restaurant News, 1995).

Cost Control

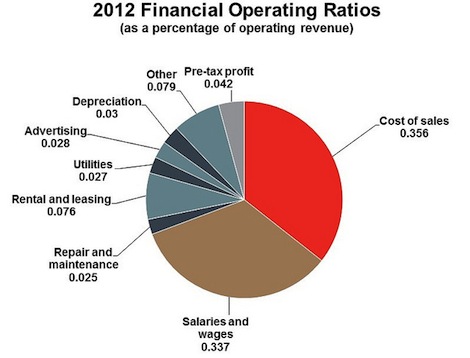

According to Restaurants Canada, QSRs have the highest profit margin at 5.1%, while full-service restaurants have a margin of 3.5%. There will be significant variances from these percentages at individual locations even within the same brand (2014b).

A number of costs influence the profitability of an F&B operation. Some of the key operating expenses (as a percentage of revenue) are detailed in Figure 4.12, above, where food cost and salaries & wages are the two major expenses, each accounting for approximately a third of the total. Other expenses include rental and leasing of venue, utilities, advertising, and depreciation of assets. These percentages represent averages, and will vary greatly by sector and location.

Cost control and containment is essential for all F&B businesses. Demanding particular attention are the labour, food, and beverage costs, also known as the operator’s primary costs. In addition to these big ticket items, there is the cost of reusable operating supplies such as cutlery, glassware, china, and linen in full-service restaurants.

Given that most operations have both a service side (interacting directly with the consumer) and production side (preparing food or drink to be consumed), the primary costs incurred during these activities often determine the feasibility or success of the operation. This is especially true as the main product (e.g., food and drink) is perishable; ordering the correct amount requires skill and experience.

Take a Closer Look: Survey of Service Industries -- Foodservices and Drinking Places

The Statistics Canada Survey of Service Industries series features an in-depth look at the food and beverage sector. Data used in this chapter (and much more) can be found in this comprehensive overview. To explore the survey, visit the Survey of Service Industries: www23.statcan.gc.ca/imdb/p3Instr.pl?Function=assembleInstr&Item_Id=137106&LI=137106&TET=1

Sales and Marketing

The two principal considerations for sales and marketing in this sector are market share and revenue maximization. Most F&B operations are constrained by finite time and space, so management must constantly seek ways to increase revenue from the existing operation, or increase the share of the available market. Examples of revenue maximization include upselling existing consumers (e.g., asking if they want fries with their meal; offering dessert), and using outdoor or patio space (even using rain covers and heaters to extend the outdoor season). Examples of increasing market share in the fast-food sector include extending special offers to new, first-time customers through social media or targeted direct mail.

In today’s cluttered marketplace, being noticed is a constant goal for most companies. Converting that awareness into patronage is a challenge for most operators. Restaurant reviews have been a part of the food and beverage sector for a long time. With the increase of online reviews by customers at sites like Yelp, Urbanspoon, and TripAdvisor, and sharing of experiences via social media, food and beverage operators are becoming increasingly aware of their web presence (Kwok & Yu, 2013). For this reason, all major food and beverage operators carefully monitor their online reputation and their social media presence.

Take a Closer Look: McDonald's Social Media Conversation

In 2014, McDonald's Restaurants took to the internet to answer questions about their food production and ingredients. After months of declining sales, their strategy was to create more emotional engagement with customers and to gain their trust (Passikoff, 2014). To read more about the initiative, read the article in Forbes magazine, "McDonald's Hopes New Social Media Question-And-Answer Will Modify Food Image": www.forbes.com/sites/robertpassikoff/2014/10/14/mcdonalds-hopes-new-social-media-qa-will-modify-food-image/

One of the keys to a strong reputation, both in person, and online, is the management of human resources.

Staffing and Human Resources

Appropriately staffing an F&B operation involves attracting the right people, hiring them, training them, and then assigning them to the right tasks for their skills and abilities. Many businesses operate outside the traditional workweek hours; indeed, some operate on a 24-hour schedule. Creating the right team, employing them in accordance with legal guidelines, and keeping up with the demands of the businesses are challenges that can be addressed by a well-thought-out and implemented human resources plan.

People who have long-lasting careers in the sector find the fluctuating conditions appealing; no two days are the same, and the fast-paced and energetic social environment can be motivating. Many positions provide meaningful rewards and compensation that can lead to long-term careers.

One topic of discussion in food and beverage human resources is that of gratuities (tipping). In Canada, restaurants are obligated to pay staff minimum wage, and gratuities are paid by the customer as an expression of their gratitude for service. This is not the model in countries like Australia, where service staff are paid a higher professional wage and prices are raised to accommodate this.

Take a Closer Look: Tipping and Its Alternatives

In 2008, Michael Lynn and Glenn Withiam wrote a paper discussing the role of tipping and potential alternatives. While the paper focuses particularly on the United States (where wages are structured differently from Canada), it raises some good questions about consumer preference and impact on businesses (Lynn & Withiam, 2008). For instance, do tips actually improve service? These questions can apply to food and beverage businesses but also other tourism operations within the service context. It also offers some suggestions for further research. Read this paper at "Tipping and Its Alternatives": http://scholarship.sha.cornell.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1029&context=articles

In British Columbia, tips are considered income for tax purposes but are not considered wages as they are not paid by the employer to the employee. A restaurant owner cannot use tips to cover business expenses (e.g., require an employee to use his or her tips to cover the cost of broken glassware). Employers are also not permitted to charge staff for the cost of diners who do not pay (known as a dine-and-dash). They can, however, require front-of-house staff pool their gratuities, or pay individually, to ensure back-of-house staff receive a percentage of the tips (British Columbia Ministry of Jobs, Tourism and Skills Training, n.d.). This is also commonly known as a tip-out.

There have been experiments with gratuity models in recent years. One example is a restaurant on Vancouver Island, which tried an all-inclusive pricing model upon opening in 2014, but reverted three months later to the traditional tipping model due to consumer demand and resistance to higher prices (Duffy, 2014).

Trends and Issues

In addition to having to focus on the changing needs of guests and the specific challenges of their own businesses, food and beverage operators must deal with trends and issues that affect the entire industry. Let's take a closer look at these.

Government Influence

Each level of government affects the sector in different ways. The federal government and its agencies have influence through income tax rates, costs of employee benefits (e.g., employer share of Canada Pension Plan and Employment Insurance deductions), and support for specific agricultural producers such as Canadian dairy and poultry farmers, which can lead to an increase in the price of ingredients such as milk, cheese, butter, eggs, and chicken compared to US prices (Findlay, 2014; Chapman, 1994).

Provincial governments also impact the food and beverage sector, in particular with respect to employment standards; minimum wage; sales taxes (except Alberta); liquor, wine, and beer wholesale pricing (Smith, 2015); and corporate income tax rates.

Municipal governments have an ever-increasing impact through property and business taxes, non-smoking bylaws, zoning and bylaw restrictions, user fees, and operating hours restrictions.

Spotlight On: Restaurants Canada

When Restaurants Canada was founded in 1944, it was known as the Canadian Restaurant Association, and later the Canadian Restaurant and Foodservices Association. Today, the organization represents over 30,000 operations including restaurants, bars, caterers, institutions, and suppliers. It conducts and circulates industry research and offers its members cost savings on supplies, insurance, and other business expenses. For more information, visit the Restaurants Canada website: www.restaurantscanada.org

Over time, the consequence of these government impacts has resulted in independent and chain operators alike joining forces to create a national restaurant and foodservice association now named Restaurants Canada (see Spotlight On above). At the provincial level, BC operators rely on the British Columbia Restaurant & Foodservices Association (BCRFA).

Spotlight On: BC Restaurant & Foodservices Association (BCRFA)

For more than 40 years, the BCRFA has represented the interests of the province's foodservice operators in matters such as wages, benefits, liquor licences and other relevant matters. Today, it offers benefits to over 3,000 members on both the supply and the operator side. For more information, visit the BC Restaurant and Foodservices Association website: http://bcrfa.com

Health and Safety

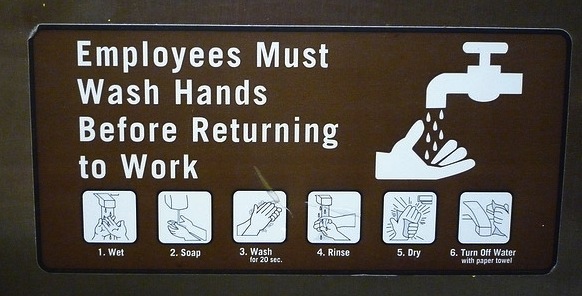

Food and beverage providers hold a distinct position within our society; they invite the public to consume their offerings, both on and off premise. In doing so, all food and beverage operators must adhere to standardized public safety regulations. Each province has regulations and legislation that apply in their jurisdiction. In BC, this is addressed by the FoodSafe and Serving It Right programs, and compliance with the Occupiers Liability Act. These regulations and legislation are enacted in the interest of public health and safety.

Take a Closer Look: Health and Safety Training

Food and beverage professionals are strongly encouraged to take both FoodSafe and Serving It Right courses. These certifications are necessary to advance into specific and leadership roles in the industry. For instance, Serving It Right is required by all licensees, managers, sales staff, and servers in licensed establishments. In addition, individuals may require Serving It Right for a special occasion licence. To sign up for an online program or course near you, visit FoodSafe: www.foodsafe.ca and Serving It Right: www.servingitright.com

FoodSafe is the provincial food safety training program designed for the foodservice industry (FoodSafe, 2009). Serving It Right is a mandatory course that is completed through self-study, and is required for anyone serving alcohol in a commercial setting. Its goal is to ensure that licensees, managers, and servers know their legal responsibilities and understand techniques to prevent over-service and related issues (go2HR, 2014).

In broad terms, BC's Occupiers Liability Act covers the responsibilities of the occupier of a property to ensure the safety of visitors. Additional local health bylaws set standards of operation for health and safety under the direction of the medical officers of health. Public health inspectors regularly visit food and beverage operations to evaluate compliance. In some communities, these inspection results are posted online.

Collectively, the food and beverage industry in BC has an excellent reputation for ensuring the health and safety of its patrons, the general public, and its employees.

Technology Trends

Technology continues to play an ever-increasing role in the sector. It is most noticeable in QSRs where many functions are automated in both the front of house and back of house. In the kitchen, temperature sensors and alarms determine when fries are ready and notify kitchen staff. Out front, remote printers or special screens ensure the kitchen is immediately notified when a server rings in a purchase. WiFi enables credit/debit card hand-held devices to be brought directly to the table to process transactions, saving steps back to the serving station.

Other trends include automated services such as that offered by Open Table, which provides restaurants with an online real-time restaurant reservation system so customers can make reservations without speaking to anyone at the restaurant (Open Table, 2015). And now smartphone apps will tell customers what restaurants are nearby or where their favourite chain restaurant is located.

Take a Closer Look: Automated Cooking in Asia

In Singapore Changi Airport, a quick-service restaurant is using automated woks. The cook adds the ingredients and can attend to other duties until the item is ready for service. Check out a video of a cook using an automated wok: www.youtube.com/watch?v=Gqiz17AsYhQ. And in China, watch a video of robots that are shaving noodles "by hand.": singularityhub.com/2013/04/19/chinese-restaurant-owner-says-robot-noodle-maker-doing-a-good-job/

Changing Venues

The following trends relate to the changing nature of food and beverage venues, including the emerging importance of the third space, and the increased mainstream presence of non-permanent locations such as street vendors and pop-up restaurants.

The Third Space

The third space is a concept that describes locations where customers congregate that are neither home (the first space) nor work or school (the second space). Many attribute the emergence of these spaces to the popularity of coffee shops such as Starbucks. In the third space, operators must create a comfortable venue for customers to "hang out" with comfortable seating, grab and go F&B options, WiFi, and a relaxed ambiance. Providing these components has been shown as a way to increase traffic and customer loyalty (Mogelonski, 2014).

Taking It to the Street

Street food has always been a component of the foodservice industry in most big cities. These operations are often run by a single owner/operator or with minimal staff, and serve hot food that can be eaten while standing. According to research firm IBISWorld, in 2011 the "street food business -- which includes mobile food trucks and non mechanized carts, is a $1 billion industry that has seen an 8.4 percent growth rate from 2007 to 2012" (Entrepreneur, 2011) with 78% of owners having no more than four employees.

Recently, in North America, where climate and weather allow, there has been a noticeable increase in both the number and type of street food vendors. In the city of Vancouver alone there are over 100 permitted food cart businesses, searchable by an app and sortable list -- and the city uses the terms street food vendor, food cart, and food truck interchangeably (City of Vancouver, 2014).

Pop-up restaurants have also emerged, facilitated in part by the prevalent use of social media for marketing and location identification. Pop-ups are temporary restaurants with a known expiry date, which also tend to have the following in common (Knox, 2011):

- A well-known or up-and-coming chef at the helm

- An interesting, but stationary, location (a warehouse, a park, the more unusual the better)

- Staff who are adept at promotions and word-of-mouth

- Strong local foodie (food and beverage enthusiast) base in the area

- Involvement from local artists or musicians to add to the experience

As popular they are with consumers, the ways in which pop-ups deviate from restaurants has aggravated some critics, causing Bon Appétit magazine to declare that "pop-ups are not supposed to be restaurants," and that "pop-up restaurants are over" (Duckor, 2013). Statements like these are further evidence that food and beverage services trends are dynamic and ever-changing.

Conclusion

The food and beverage sector is a vibrant and multifaceted part of our society. Michael Hurst, famous restaurateur and former chair of the US National Restaurant Association, championed the idea that all guests should be received with the statement "Glad you are here" (Tripp, 1992; Marshall 2001). That statement is the perfect embodiment of what F&B is to the hospitality industry — a mix of service providers who welcome guests with open arms and take care of their most basic needs, as well as their emotional well-being.

Take a Closer Look: Michael Hurst

Michael Hurst preached to students, industry participants, and university colleagues alike, saying that “The most precious gift you can give your Guests is the gift of Friendship" (Tripp, 1992; Marshall 2001). To learn more about this legendary character, visit In My Opinion: Michael E. Hurst [PDF]: http://digitalcommons.fiu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1353&context=hospitalityreview

The social fabric of our country, its residents, and visitors will change over time, and so too will F&B. What will not change in spite of how we divide the segments — into tourists or locals — is that the sector is at its best when food and beverages are accompanied by a social element, extending from your dining companions to the front and back of the house.

So far, we have covered the transportation, accommodation, and food and beverage sectors. In the next two chapters, we'll explore the recreation and entertainment sector, starting with recreation in Chapter 5.

Key Terms

- Assets: items of value owned by the business and used in the production and service of the dining experience

- Average cheque: total sales divided by number of guests served

- Back of house: food production areas not accessible to guests and not generally visible; also known as heart of house

- BC Restaurant & Foodservices Association (BCRFA): representing the interests of more than 3,000 of the province's foodservice operators in matters including wages, benefits, liquor licences, and other relevant matters

- Beverage costs: beverages sold in liquor-licensed operations; this usually only includes alcohol, but in unlicensed operations, it includes coffee, tea milk, juices, and soft drinks

- Captured patrons: consumers with limited selection or choice of food or beverage provider given their occupation or location

- Commercial foodservice: operations whose primary business is food and beverage

- Cross-utilization: when a menu is created to make multiple uses of a small number of staple pantry ingredients, helping to keep food costs down

- Dine-and-dash: the term commonly used in the industry for when a patron eats but does not pay for his or her meal

- Ethnic restaurant: a restaurant based on the cuisine of a particular region or country, often reflecting the heritage of the head chef or owner

- Family/casual restaurant: restaurant type that is typically open for all three meal periods, offering affordable prices and able to serve diverse tastes and accommodate large groups

- Fine dining restaurant: licensed food and beverage establishment characterized by high-end ingredients and preparations and highly trained service staff

- Food and beverage (F&B): type of operation primarily engaged in preparing meals, snacks, and beverages, to customer order, for immediate consumption on and off the premises

- Food cost: price including freight charges of all food served to the guest for a price (does not include food and beverages given away, which are quality or promotion costs)

- Food primary: a licence required to operate a restaurant whose primary business is serving food (rather than alcohol)

- Foodie: a term (often used by the person themselves) to describe a food and beverage enthusiast

- Front of house: public areas of the establishment; in quick-service restaurants, it includes the ordering and product serving area

- Full-service restaurants: casual and fine dining restaurants where guests order food seated and pay after they have finished their meal

- Liquor primary licence: the type of licence needed in BC to operate a business that is in the primary business of selling alcohol (most pubs, nightclubs, and cabarets fall into this category)

- Non-commercial foodservice: establishments where food is served, but where the primary business is not food and beverage service

- Operating supplies: generally includes reusable items including cutlery, glassware, china, and linen in full-service restaurants

- Pop-up restaurants: temporary restaurants with a known expiry date hosted in an unusual location, which tend to be helmed by a well-known or up-and-coming chef and use word-of-mouth in their promotions

- Primary costs: food, beverage, and labour costs for an F&B operation

- Profit: the amount left when expenses (including corporate income tax) are subtracted from sales revenue

- Quick-service restaurant (QSR): an establishment where guests pay before they eat; includes counter service, take-out, and delivery

- Restaurants Canada: representing over 30,000 food and beverage operations including restaurants, bars, caterers, institutions, and suppliers

- Revenue: sales dollars collected from guests

- Third space: a term used to describe F&B outlets enjoyed as "hang out" spaces for customers where guests and service staff co-create the experience

- Tip-out: the practice of having front-of-house staff pool their gratuities, or pay individually, to ensure back-of-house staff receive a percentage of the tips

- Upscale casual restaurant: emerging in the 1970s, a style of restaurant that typically only serves dinner, intended to bridge the gap between fine dining and family/casual restaurants

Exercises

- Looking at Table 4.1, what was the average volume of sales per F&B establishment in BC in 2013? What was it for Alberta? What about the national average? What might account for these differences? List at least three contributing factors.

- Looking at the same table, how many F&B "units" were there in BC in 2013?

- What are the two main classifications for food and beverage operations and which is significantly larger in terms of market share?

- Should gratuities be abolished in favour of all-inclusive pricing? Consider the point of view of the server, the owner, and the guest in your analysis.

- Think of the concept of the third space, and name two of these types of operations in your community.

- Have you worked in a restaurant or foodservice operation? What are the three important lessons you learned about work while there? If you have not, interview a classmate who has experience in the field and find out what three lessons he or she would suggest.

- What is your favourite restaurant? What does it do so well to have become your favourite? What would you recommend it do to improve your dining experience even more?

- What was your all-time best restaurant dining experience? Compare and contrast this with one of your worst dining experiences. For each of these, include a description of:

- The food

- The behaviour of restaurant staff

- Ambiance (music, decor, temperature, comfort of chairs, lighting)

- The reason for your visit

- Your mood upon entering the establishment

Case Study: Restaurant Behaviour -- Then and Now

The following story made the rounds via social media in late 2014. While the claim has not been verified, it certainly rings true for a number of F&B professionals who have experienced this phenomenon. The story is as follows:

A busy New York City restaurant kept getting bad reviews for slow service, so they hired a firm to investigate. When they compared footage from 2004 to footage from 2014, they made some pretty startling discoveries. So shocking, in fact, that they ranted about it in an anonymous post on Craigslist:

We are a popular restaurant for both locals and tourists alike. Having been in business for many years, we noticed that although the number of customers we serve on a daily basis is almost the same as ten years ago, the service seems very slow. One of the most common complaints on review sites against us and many restaurants in the area is that the service was slow and/or they needed to wait too long for a table. We've added more staff and cut back on the menu items but we just haven't been able to figure it out.

We hired a firm to help us solve this mystery, and naturally the first thing they blamed it on was the employees needing more training and the kitchen staff not being up to the task of serving that many customers.

Like most restaurants in NYC we have a surveillance system, and unlike today where it's digital, 10 years ago we still used special high capacity tapes to record all activity. At any given time we had 4 special Sony systems recording multiple cameras. We would store the footage for 90 days just in case we needed it for something.

The investigators suggested we locate some of the older tapes and analyze how the staff behaved ten years ago versus how they behave now. We went down to our storage room but we couldn't find any tapes at all.

We did find the recording devices, and luckily for us, each device has 1 tape in it that we simply never removed when we upgraded to the new digital system!

The date stamp on the old footage was Thursday July 1, 2004. The restaurant was very busy that day. We loaded up the footage on a large monitor, and next to it on a separate monitor loaded up the footage of Thursday July 3 2014, with roughly the same amount of customers as ten years before.

We carefully looked at over 45 transactions in order to determine what has been happening:

Here's a typical transaction from 2004:

Customers walk in. They are seated and are given menus. Out of 45 customers 3 request to be seated elsewhere.

Customers spend 8 minutes on average before closing the menu to show they are ready to order.

Waiters shows up almost instantly and takes the order.

Appetizers are fired within 6 minutes; obviously the more complex items take longer.

Out of 45 customers 2 sent their items back.

Waiters keep an eye on their tables so they can respond quickly if the customer needs something.

After guests are done, the check is delivered, and within 5 minutes they leave.

Average time from start to finish: 1 hour, 5 minutes.

Here's what happened in 2014:

Customers walk in. Customers get seated and are given menus, and out of 45 customers 18 request to be seated elsewhere.

Before even opening the menu most customers take their phones out, some are taking photos while others are texting or browsing.

Seven of the 45 customers had waiters come over right away, they showed them something on their phone and spent an average of five minutes of the waiter's time. Given this is recent footage, we asked the waiters about this and they explained those customers had a problem connecting to the WIFI and demanded the waiters try to help them.

After a few minutes of letting the customers review the menu, waiters return to their tables. The majority of customers have not even opened their menus and ask the waiter to wait a bit.

When customers do open their menus, many place their phones on top and continue using their activities.

Waiters return to see if they are ready to order or have any questions. Most customers ask for more time.

Finally a table is ready to order. Total average time from when a customer is seated until they place their order is 21 minutes.

Food starts getting delivered within 6 minutes; obviously the more complex items take way longer.

26 out of 45 customers spend an average of 3 minutes taking photos of the food.

14 out of 45 customers take pictures of each other with the food in front of them or as they are eating the food. This takes on average another 4 minutes as they must review and sometimes retake the photo.

9 out of 45 customers sent their food back to reheat. Obviously if they didn't pause to do whatever on their phone the food wouldn't have gotten cold.

27 out of 45 customers asked their waiter to take a group photo. 14 of those requested the waiter retake the photo as they were not pleased with the first photo. On average this entire process between the chit chatting and reviewing the photo taken added another 5 minutes and obviously caused the waiter not to be able to take care of other tables he/she was serving.

Given in most cases the customers are constantly busy on their phones it took an average of 20 more minutes from when they were done eating until they requested a check.

Furthermore once the check was delivered it took 15 minutes longer than 10 years ago for them to pay and leave.

8 out of 45 customers bumped into other customers or in one case a waiter (texting while walking) as they were either walking in or out of the restaurant.

Average time from start to finish: 1:55

We are grateful for everyone who comes into our restaurant, after all there are so many choices out there. But can you please be a bit more considerate?

Now it's your turn. Imagine you are the restaurant operator in question, and answer the questions below.

- What could you, as the owner, try to do to improve the turnover time? Come up with at least three ideas.

- Now put yourself in the position of a server. Do your ideas still work from this perspective?

- Lastly, look at your typical customer. How will he or she respond to your proposals?

References

British Columbia Ministry of Jobs, Tourism and Skills Training. (n.d.). <a href="http://www.labour.gov.bc.ca/esb/igm/esa-part-1/igm-esa-s1-wages.htm#top" target="_self"Interpretation guidelines manual, Employment Standards Branch. Retrieved from >www.labour.gov.bc.ca/esb/igm/esa-part-1/igm-esa-s1-wages.htm#top

Chapman, Anthony. (1994). Reduction of tariffs on supply managed commodities under the GATT and the NAFTA, tarrification under the Uruguay Round. Retrieved from: http://publications.gc.ca/Collection-R/LoPBdP/BP/bp380-e.htm

City of Vancouver. (2014, June 30). Find a street food vendor. Retrieved from http://vancouver.ca/people-programs/find-a-food-truck-vendor.aspx

Duckor, M. (2013, June 27). Pop-up restaurants are over. Bon Appétit. Retrieved from www.bonappetit.com/restaurants-travel/article/pop-up-restaurants-are-over

Duffy, A. (2014, August 22). Vancouver Island restauranteur regretfully ends his no-tip policy. Vancouver Sun. Retrieved from www.vancouversun.com/news/metro/Vancouver+Island+restaurateur+regretfully+ends+policy/10140961/story.html

Entrepreneur. (2011, July 24). Food trucks 101: How to start a mobile food business. Retrieved from www.entrepreneur.com/article/220060

Findlay, M. (2014, May 12). Why your milk costs so much and what to do about it. Macleans. Retrieved from www.macleans.ca/economy/economicanalysis/why-your-milk-costs-so-much-in-canada/

FoodSafe. (2009). Welcome. Retrieved from www.foodsafe.ca

Frash, R. E., DiPietro, R., & Smith, W. (2014). Pay more for McLocal? Examining motivators for willingness to pay for local food in a chain restaurant setting. Journal of Hospitality Marketing & Management, 24(4), 411-434.

Georgia Straight. (2015). Bishop's. Retrieved from www.straight.com/listings/venues/114986

go2HR. (2014). Serving-it-Right. Retrieved from www.servingitright.com

Government of Canada. (2012, June 14). NAICS 2012 - 722 - Food services and drinking places. Retrieved from: www23.statcan.gc.ca/imdb/p3VD.pl?Function=getVD&TVD=118464&CVD=118466&CPV=722&CST=01012012&CLV=2&MLV=5

Heroux, L. (2002). Restaurant marketing strategies in the United States and Canada: A comparative study. Journal of Foodservice Business Research, 5(4), 95-110.

Knox, J. (2011, June 13). Ingredients for a successful pop-up restaurant. Restaurant Central.ca. Retrieved from http://restaurantcentral.ca/popuprestaurant.aspx

Koc, M., & Welsh, J. (2001). Food, foodways and immigrant experience. Toronto: Centre for Studies in Food Security.

Kwok, L., & Yu, B. (2013). Spreading social media messages on Facebook. An analysis of restaurant business-to-consumer communications. Cornell Hospitality Quarterly, 54(1), 84-94.

Laroche, M., Kim, C., Tomiuk, M. A., & Belisle, D. (2005). Similarities in Italian and Greek multidimensional ethnic identity: Some implications for food consumption. Canadian Journal of Administrative Sciences/Revue Canadienne des Sciences de l'Administration, 22(2), 143-167.

LinkBC. (2014, June). 2014 Roundtable Dialogue Cafe Report. [PDF] Retrieved from http://linkbc.ca/siteFiles/85/files/2014RoundtableDialogueCafeReport.pdf

Lynn, M., & Withiam, G. (2008). Tipping and its alternatives: Business considerations and directions for research. Journal of Services Marketing, 22(4), 328-336.

Mak, A. H., Lumbers, M., & Eves, A. (2012). Globalisation and food consumption in tourism. Annals of Tourism Research, 39(1), 171-196.

Mak, A. H., Lumbers, M., Eves, A., & Chang, R. C. (2012). Factors influencing tourist food consumption. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 31(3), 928-936.

Marshall, A. G. (2001). In my opinion: Michael E. Hurst: July 8, 1931-March 22, 2001. Hospitality Review, 19(2), 9.

Mogelonski, L. (2014, January 3). Third spaces enrich guests' lives. Hotel News Now. Retrieved from http://hotelnewsnow.com/Article/12908/Third-spaces-enrich-guests-lives-and-loyalty

Ontario Restaurant News. (1995). Selecting a restaurant site is key to franchise unit's success. Reprinted in FGHI. Retrieved from www.fhgi.com/publications/articles/selecting-a-restaurant-site-is-key-to-franchise-units-success/

Open Table, Inc. (2015). Make restaurant reservations the easy way. Retrieved from www.opentable.com/start/home

Parsa, H. G., Lord, K. R., Putrevu, S., & Kreeger, J. (2015). Corporate social and environmental responsibility in services: Will consumers pay for it?. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 22, 250-260.

Passikoff, Robert. (2014, November, 14). McDonald’s hopes new social media question-and-answer will modify food image. Forbes. Retrieved from www.forbes.com/sites/robertpassikoff/2014/10/14/mcdonalds-hopes-new-social-media-qa-will-modify-food-image/

Restaurants Canada (2014a). Foodservice facts. Retrieved from https://www.restaurantscanada.org/en/Book-Store/Product/rvdsfpid/2013-foodservice-facts-7

Restaurants Canada (2014b). Market review and forecast 2014. Retrieved from https://restaurantscanada.org

Restaurants Canada, Statistics Canada, fsSTRATEGY Inc. and Pannell Kerr Forster. (2013). Sector sales and market shares for 2012/13. Retrieved from www.restaurantscanada.org/en/Research#crfaResearchReports

Schlosser, E. (2012). Fast food nation: The dark side of the all-American meal. New York, NY: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt.

Smart, J. (2003). Ethnic entrepreneurship, transmigration, and social integration: an ethnographic study of Chinese restaurant owners in rural western Canada. Urban Anthropology and Studies of Cultural Systems and World Economic Development, 311-342.

Smith, C. (2015, March 25). BC Liberal government liquor reforms pinch private retailers. Georgia Straight. Retrieved from www.straight.com/food/416961/bc-liberal-government-liquor-reforms-pinch-private-retailers

State Sales Tax Rates. (2015). Retrieved from www.sale-tax.com

Statistics Canada, Restaurants Canada, Recount/NDP Group. (2013). Performance by Province (Commercial Foodservice). Retrieved from www.restaurantscanada.org/en/Research

Tripp, Griff. (1992). Personal knowledge.

Attributions

Figure 4.1 Foodservice Share of Total FoodDollars by LinkBC is used under a CC-BY-NC 2.0 license.

Figure 4.2 Profit Margins for Restaurants by Province by LinkBC is used under a CC-BY-NC 2.0 license.

Figure 4.3 The Keg at the Station by Jon the Happy Web Creative is used under a CC BY 2.0 license.

Figure 4.4 North Arm Farm Strawberry + Rhubarb Pavlova by Ruth Hartnup is used under a CC-BY 2.0 license.

Figure 4.5 The old spaghetti factory by Isabelle Puaut is used under a CC BY-NC-ND 2.0 license.

Figure 4.6 Vij's by jan zeschky is used under a CC-BY-NC 2.0 license.

Figure 4.7 Dîner en Blanc Vancouver 2012 by Maurice Li Photography is used under a CC BY-NC-ND 2.0 license.

Figure 4.8 Six Mile by Alan Levine is used under a CC BY-SA 2.0 license.

Figure 4.9 Market Share by Restaurant Segment by LinkBC is used under a CC-BY-NC 2.0 license.

Figure 4.10 Life goal #5 complete by Brett Ohland is used under a CC BY-NC-SA 2.0 license.

Figure 4.11 New funding for farmers' market program by Province of British Columbia is used under a CC BY-NC-ND 2.0 license.

Figure 4.12 Operating Ratios for Canadian Foodservice Businesses by LinkBC is used under a CC-BY-NC 2.0 license.

Figure 4.13 Cactus Club Cafe by Mack Male used under CC BY-SA 2.0 license.

Figure 4.14 must wash hands by Ambernectar13 is used under CC BY-ND 2.0 license.

Figure 4.15 Vancouver food carts on a sunny day by Christopher Porter is used under a CC BY-NC-ND 2.0 license.

Long Descriptions

| Country | 2001 | 2002 | 2003 | 2004 | 2005 | 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Percentage of food money spent on foodservices by Americans | 46.4% | 46.7% | 47.5% | 47.9% | 46.7% | 47.5% | 47.9% | 48% | 48% | 49% | 49% | 48% | 47% | 47.6% | 47% |

| Percentage of food money spent on foodservices by Canadians | 40.2% | 40.0% | 39.2% | 39.3% | 39.1% | 39.2% | 38.8% | 38.4% | 37.0% | 36.7% | 36.7% | 37.3% | 37.7% | 38.2% | 38.5% |

| Province | Pre-Tax profit margin |

|---|---|

| Manitoba | 7.9% |

| Alberta | 7.1% |

| Saskatchewan | 7.0% |

| Newfoundland and Labrador | 6.7% |

| Prince Edward Island | 5.7% |

| New Brunswick | 5.2% |

| Nova Scotia | 5.2% |

| Canada | 4.2% |

| Quebec | 3.9% |

| British Columbia | 3.4% |

| Ontario | 2.8% |

| Quick Service Restaurants | Family/Midscale | Casual Dining | Fine Dining | Retail | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Share of Traffic | 64.5% | 13.2% | 10.1% | 0.7% | 11.5% |

| Share of Dollars | 45.8% | 20.6% | 22.5% | 4.2% | 6.9% |

| Expense | Percentage of operating revenue |

|---|---|

| Cost of Sales | 35.6% |

| Salaries and wages | 33.7% |

| Other | 7.9% |

| Rental and Leasing | 7.6% |

| Pre-Tax profit | 4.2% |

| Depreciation | 3.0% |

| Advertising | 2.8% |

| Utilities | 2.7% |

| Repair and Maintenance | 2.5% |