Chapter 12. Aboriginal Tourism

Keith Henry and Terry Hood

Learning Objectives

- Describe the socio-political context for Aboriginal tourism development

- Identify steps taken to uphold indigenous rights as they relate to tourism in developing nations

- Discuss the evolution of Aboriginal tourism in Canada and its connection to cultural/heritage tourism

- Describe approaches taken to strengthen and increase the number of Aboriginal tourism businesses in Canada and BC

- Describe the stages of market readiness and how these relate to Aboriginal tourism products and experiences

- Explain the concept of authenticity and the challenges in delivering authentic visitor experiences

- Articulate the importance of community involvement and effective partnerships in developing Aboriginal tourism businesses

- Recognize the value of Aboriginal tourism to BC’s tourism industry, and key agencies responsible for its development

- Relate success stories in Aboriginal tourism business operations and collaborations in BC, Canada, and elsewhere

Overview

In previous chapters, you’ve learned that Aboriginal tourism is an increasingly central part of BC’s tourism economy. In Canada, tourism operations that are majority owned and operated by First Nations, Métis, and Inuit people comprise this segment of the industry. This chapter explores the global context for Aboriginal tourism development, the history of the sector in BC, and important facts about Aboriginal tourism in BC today.

Today’s travellers are attracted to many global destinations because of the opportunity to interact with, and learn from, other cultures. Visitors to Australia can meet an Aboriginal guide who will help them feel a spiritual connection through a memorable outback experience. In New Zealand (Aotearoa in the Maori language), tourists are often welcomed into a ceremonial community marae, a communal or sacred centre that serves a religious and social purpose in Polynesian societies (New Zealand Maori Tourism Society, 2012).

In the mountainous region of northern Vietnam, traditionally dressed ethnic minority villagers are now opening their homes to international trekkers, thus generating new income for the community. In the United States, visitors to the ancient desert wonders of Monument Valley can enhance their experience in a Navaho-run hotel, enjoying indigenous cuisine while learning about the cultures of the Native American groups that have lived there for centuries.

Globally, indigenous peoples are those groups protected under international or national legislation as having specific rights based on their historical ties to a particular territory and their cultural or historical distinctiveness from other populations (Coates, 2004). Indigenous people in Canada are often called First peoples or Aboriginal peoples and have diverse languages, ceremonies, traditions, and histories. The Canadian Constitution Act recognizes three groups of Aboriginal people: First Nations, Inuit, and Métis.

Before learning more about Canadian First peoples and their social and cultural connections to tourism, let’s acknowledge the often negative impacts of recent history on indigenous peoples around the globe. Current attempts to influence positive change in this area will then be highlighted.

Tourism and Indigenous Human Rights

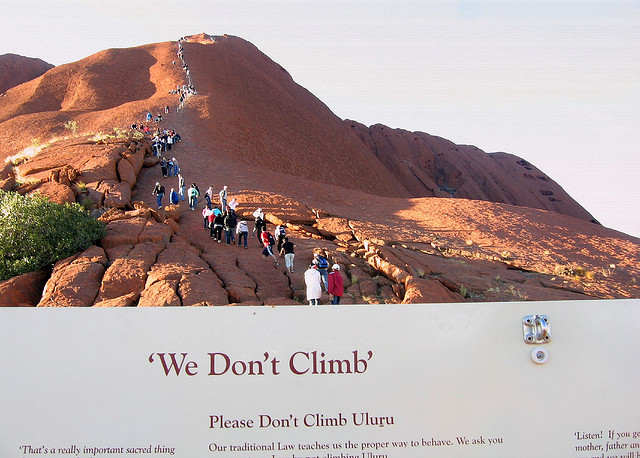

The history of tourism has seen considerable exploitation of indigenous peoples. Land has been expropriated, economic activity suppressed by outside interests, and cultural expressions (such as arts and crafts) have been appropriated by outside groups. Appropriation refers to the act of taking something for one’s own use, typically without the owner’s permission.

In recognition of these wider concerns, in 2007, the United Nations created the Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous People. This marked a significant achievement in obtaining international recognition of key rights, including, but not limited to, self-determination, land use, and natural resources rights. It set forth the minimum standards for the survival, dignity, and well-being of the indigenous peoples of the world (United Nations, 2007).

Spotlight On: International Institute for Peace through Tourism

Started in Vancouver in 1988, the International Institute for Peace through Tourism (IIPT) is now based in Africa and promotes the value of travel and cross-cultural exchange as a key potential contributor to global peace. It promotes tourism for its role in intercultural dialogue and exchanges, and supports indigenous communities’ right to self-determination. For more information, visit the International Institute for Peace through Tourism website: www.iipt.org

Themes related to indigenous tourism were raised at this time, but it was not until 2012 that the Pacific Asia Travel Association organized a gathering of global indigenous tourism professionals to establish guiding principles for the development of indigenous tourism. These principles are now known as the Larrakia Declaration on the Development of Indigenous Tourism, named after the Larrakia Nation, the Australian Aboriginal host community for the meeting (PATA & WINTA, 2014).

Spotlight On: World Indigenous Tourism Alliance

World Indigenous Tourism Alliance (WINTA) was formed in Australia in 2012 during the same gathering that created the Larrakia Declaration. A global network, it is made up of over 170 indigenous and non-indigenous organizations in 40 countries, such as tourism associations, businesses, service providers, and government groups. For more information, visit the World Indigenous Tourism Alliance websitewww.winta.org

The Larrakia Declaration

According to the Larrakia Declaration, these are the key principles that should guide all culturally respectful indigenous tourism business development (World Indigenous Tourism Alliance, 2012, pp. 1-2):

“It is hereby resolved to adopt the following principles; that …

- Respect for customary law and lore, land and water, traditional knowledge, traditional cultural expressions, cultural heritage that will underpin all tourism decisions.

- Indigenous culture, the land and waters on which it is based, will be protected and promoted through well managed tourism practices and appropriate interpretation.

- Indigenous peoples will determine the extent, nature and organisational arrangements for their participation in tourism and that governments and multilateral agencies will support the empowerment of Indigenous people.

- That governments have a duty to consult and accommodate Indigenous peoples before undertaking decisions on public policy and programs designed to foster the development of Indigenous tourism.

- The tourism industry will respect Indigenous intellectual property rights, cultures and traditional practices, the need for sustainable and equitable business partnerships and the proper care of the environment and communities that support them.

- That equitable partnerships between the tourism industry and Indigenous people will include the sharing of cultural awareness and skills development which support the well-being of communities and enable enhancement of individual livelihoods.”

Using these guiding principles, it becomes clear that Aboriginal tourism development can be considered successful only if the rights of indigenous people are upheld.

Take a Closer Look: UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous People

In 2007, the United Nations passed a declaration to address human rights violations against indigenous people. The document, sometimes known as UNDRIP, contains 46 articles, one of which is “Every indigenous individual has the right to a nationality” (United Nations, 2007, p. 5). For more information, read the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous People [PDF]: www.un.org/esa/socdev/unpfii/documents/DRIPS_en.pdf

Before turning our attention to Canadian and BC Aboriginal tourism examples, let’s briefly consider the context in which these activities in tourism are occurring, and review more important definitions. We can do this by taking a closer look at Canada’s First peoples.

First Peoples in Canada

First Peoples: A Guide for Newcomers (Wilson & Henderson, 2014) is an excellent resource for tourism professionals who want to know more about the complex socio-political issues surrounding Aboriginal people in Canadian history and society today. This section contains highlights from this guide.

In 2011, approximately 1.4 million people in Canada identified themselves as Aboriginal — roughly 4.3% of the total population.

First Nations people are Aboriginal peoples who do not identify as Inuit or Métis. They have lived across present-day Canada for thousands of years and have numerous languages, cultures, and spiritual beliefs. For centuries, they managed their lands and resources with their own governments, laws, and traditions, but with the formation of the country of Canada, their way of life was changed forever. The government forced a system of band governance on First Nations so that they could no longer use their system of government. There are now 203 bands in BC, and 614 across the country (Wilson & Henderson, 2014).

Colonial settlement has left a legacy of land displacement, economic deprivation, and negative health consequences that Canada’s First Nations are still striving to overcome (Wilson & Henderson, 2014). However, First Nations people are working hard to reclaim their traditions, and in many places there is an increasing pride in a revitalized culture.

Indian (or Native Indian) is still an important legal term in Canada, but many Aboriginal people associate it with government regulation and colonialism and its use has gone out of favour, unlike in the United States where American Indian is still common (Wilson & Henderson, 2014).

Inuit have lived in the Arctic region of Canada for countless years. Many Inuit still rely on the resources of the land, ice, and sea to maintain traditional connections to the land. The old ways of life were seriously compromised, however, when Inuit began to participate with European settlers in the fur trade. The Government of Canada accelerated this change by requiring many Inuit communities to move away from their traditional hunting and gathering ways of life on the land and into permanent, centralized settlements (Wilson & Henderson, 2014).

Spotlight On: Inuit Tapiriitt Kanatami

Inuit Tapiriitt Kanatami (ITK) is the national Inuit organization in Canada. It represents four regions: Nunatsiavut (Labrador), Nunavik (northern Quebec), Nunavut, and the Inuvialuit Settlement Region in the Northwest Territories. It is an advocacy organization that represents the interests of Inuit in environmental, social, political, and economic affairs, including economic and tourism development. For more information, visit the Inuit Tapiriitt Kanatami website: www.itk.ca

Today, in spite of social and economic hardships created by this change, many Inuit communities focus on protecting their traditional way of life and language. Recently the inukshuk, an Inuit symbol used as a welcoming signpost for hunters, was used as a key emblem for the 2010 Olympic and Paralympic Games.

Note that non-Inuit people used to call Inuit people Eskimo, but this is now considered insulting and should be avoided (Wilson & Henderson, 2014).

Métis comes from the words to mix. In the 1600s and 1700s, many French and Scottish men migrated to Canada for the fur trade. Some of them had children with First Nations women and formed new communities, and their people became the first to be called Métis. Today, the infinity symbol on the Métis flag symbolizes the joining of two cultures that will live forever.

Spotlight On: Louis Riel Institute

The Louis Riel Institute in Winnipeg is dedicated to the preservation and celebration of Métis culture and supporting Métis in achieving their educational, career, and life goals. Its website features photographs and descriptions of Métis art and handicrafts as well as information about community programs. For more information, visit the Louis Riel Institute website: www.louisrielinstitute.com

The distinct Métis culture is known for its fine beadwork, fiddling, and jigging. Canadian and international tourists can learn from and enjoy participating in a large number of Métis festivals in most provinces across the country.

Take a Closer Look: Métis Nation Gateway

This portal site features information about the Métis Nation, including healing, economic development, environment, electoral reform, veterans’ issues, and more. The portal on economic development leads to information on community development, including tourism policy and plans [PDF]. To explore these resources, visit Métis Nation Gateway: http://metisportals.ca/wp/

There is an increasing appreciation that intercultural exchanges can help strengthen cultures at risk, if managed thoughtfully. For example, the growing niche of Arctic cruise tourism has brought both opportunities and challenges to the isolated small communities of Canada’s rugged Arctic coast. In recognition, the World Wildlife Fund produced a Code of Conduct for Arctic tourists. In part it reads:

Respect Local Cultures:

- Learn about the culture and customs of the areas you will visit before you go.

- Respect the rights of Arctic residents. You are most likely to be accepted and welcomed if you travel with an open mind, learn about local culture and traditions, and respect local customs and etiquette.

- If you are not travelling with a tour, let the community you will visit know that you are coming.

- Supplies are sometimes scarce in the Arctic, so be prepared to bring your own.

- Ask permission before you photograph people or enter their property or living spaces.”

(WWF International Arctic Programme, n.d., p. 2)

Tourism can promote community and economic development while preserving indigenous culture. With that in mind, let’s have a look at the evolution of Aboriginal tourism in Canada, and at some strategies to advance this segment of the industry.

Aboriginal Tourism in Canada

Evolution of Aboriginal Tourism in Canada

While there has always been some demand among visitors to Canada to learn more about Aboriginal heritage, driven by the strong interest of Europeans in particular, until recently there has been no concerted effort to focus on defining and strengthening Aboriginal cultural tourism. However, over the last 20 years or so, steps have been taken to support authentic Aboriginal cultural products and experiences and to counter decades of appropriation of Aboriginal symbols and arts and crafts by non-Aboriginal Canadians.

Aboriginal exhibits and displays were developed for tourism attractions and museums by well-meaning non-Aboriginals who did not consult with local communities. Souvenir shops were often filled with inexpensive overseas-made replicas of authentic Aboriginal arts and crafts, and some still are. To this day, we see the Canadian Prairie Aboriginal headdress being used as a way of (mis)representing First Nations across Canada.

As the number of Aboriginal tourism businesses started to increase in the 1980s and 1990s, the federal government initiated discussions on Aboriginal tourism. The outcome was the formation of national organizations that provided a coordinated industry voice for operators: Aboriginal Tourism Team Canada (ATTC), Aboriginal Tourism Canada, and Aboriginal Tourism Marketing Circle (ATMC), and others. These groups started the trend of defining Aboriginal cultural tourism standards and promoting the establishment of regional, provincial, and territorial organizations to develop and market more successful businesses. Today, these functions are performed by the Aboriginal Tourism Association of Canada (ATAC).

Spotlight On: Aboriginal Tourism Association of Canada

Aboriginal Tourism Association of Canada (ATAC) is a consortium of over 20 Aboriginal tourism industry organizations and government representatives from across Canada. It was formed to create a unified voice and was formalized in 2014 (building from the ATMC established in 2009). ATAC continues to evolve to support marketing, product development and training standards, and other initiatives. For more information, visit the Aboriginal Tourism Association of Canada: www.aboriginalcanada.ca

Aboriginal Tourism in Canada Today

Despite challenges such as appropriation, thanks to these organizations, tourism is becoming a major economic and cultural driver for Aboriginal communities across Canada. It is estimated that in 2014 “Aboriginal tourism provided over 37,000 jobs in Canada and generated almost $3 billion in gross output into the Canadian economy … up substantially since 2002 where jobs were estimated at 13,000 and gross output was estimated at $2.3 billion” (O’Neil et al., 2014, p. i-xii).

To define this segment of the industry, the Aboriginal Tourism Association of Canada (2013, p. 4) uses these terms:

Aboriginal tourism: describes all tourism businesses that are majority-owned and operated by First Nations, Métis and Inuit. They must also demonstrate a connection and responsibility to the local Aboriginal community and traditional territory where the operation resides.

Aboriginal cultural tourism: meets the Aboriginal tourism criteria and in addition, a significant portion of the experience incorporates Aboriginal culture in a manner that is appropriate, respectful and true to the Aboriginal culture being portrayed. The authenticity is ensured through the active involvement of Aboriginal people in the development and delivery of the experience.

Aboriginal cultural experiences: offer the visitor a cultural experience in a manner that is appropriate, respectful and true to the Aboriginal culture being portrayed.

Take a Closer Look: Aboriginal Tourism Opportunities for Canada

This 2008 document from the Canadian Tourism Commission looks at the growing opportunities for Aboriginal tourism development, and promotion to overseas markets including the UK, Germany, and France. It includes market research and consumer data as well as an examination of ways to partner with the travel services sector. To view the report, visit Aboriginal Tourism Opportunities [PDF]: http://en-corporate.canada.travel/sites/default/files/pdf/Research/Product-knowledge/Aboriginal-tourism/Aboriginal_Tourism_Opportunities_eng.pdf

Strengthening Aboriginal Tourism in Canada

Tourism is of significant interest to growing numbers of Aboriginal communities in Canada. If developed in a thoughtful and sensitive manner, it can have potential positive economic, cultural, and social impacts. Many communities have undertaken tourism development activities to support cultural revival, intercultural awareness, and economic growth. This growth brings jobs and career opportunities for Aboriginal people at all skill levels.

In the Aboriginal Cultural Tourism Business Planning Guide, the following are suggested as the foundational building blocks necessary to run a successful and authentic Aboriginal tourism business:

- Understand the industry, learn about cultural tourists, and develop products carefully

- Ensure experiences are culturally authentic

- Involve the community’s “culture keepers” and Elders

- Practice environmental sustainability

- Prepare an Aboriginal cultural tourism business plan

- Meet visitor expectations through staff training and excellent hospitality, provided from a cultural perspective

- Ensure an effective web and social media presence

- Build personal support networks

The guide also highlights the importance of place to the Aboriginal tourism experience. It suggests that guests leave an authentic tourism experience with a memorable collection of feelings, memories, and images that all contribute to a unique sense of place and help guests understand the culture being shared (Kanahele, 1991). In order to highlight this sense of place, operators are encouraged to reflect on and impart aspects of their culture with the following elements of their business (Aboriginal Tourism BC & CTHRC, 2013):

- Decor such as signage, displays, art, photography

- Company name

- Branding elements such as logo and website design

- Employee uniforms or dress code

- Food and beverage

- Traditional stories shared with guests

- Key words and expressions from the Aboriginal host language shared in guest interactions

These touch points create a richer, and more authentic, experience for the visitor.

As an Elder once stated, Aboriginal tourism businesses showcase “culture, heritage and traditions,” and “because these belong to the entire community, the community should have some input” (Aboriginal Tourism BC & CTHRC, 2013, p. 19). For this reason, the guide suggests operators consider the extent to which:

- Community members understand the project or business as it is being proposed

- Keepers of the culture are engaged in the development of the idea

- The business or experience reflects community values

Take a Closer Look: Aboriginal Cultural Tourism Checklist (Canada) and Maori Tourism Checklist (New Zealand)

Review the Aboriginal Cultural Tourism Business Planning Guide at Aboriginal Cultural Tourism Business Planning Guide [PDF]: http://linkbc.ca/siteFiles/85/files/ACTBPG.pdf. The Maori tourism organization in New Zealand has developed a similar guide for indigenous tourism development. To review their “tourism road map,” visit Tourism Road Map: http://maoritourism.co.nz/about/getting-started

By following these guidelines, Aboriginal tourism businesses can honour the principles outlined in the Larrakia Declaration and other similar documents.

Examples of Canadian Aboriginal Tourism Development

Over the past decades, hundreds of Aboriginal-focused tourism experiences have developed in Canada. Examples include:

- The Head-Smashed-In Buffalo Jump interpretive centre in Alberta

- Northern lights viewing with indigenous hosts at Aurora Village in Yellowknife, Northwest Territories

- Essipit whale watching with the Innu in Quebec

- Driving the Great Spirit Circle Trail of Aboriginal experiences on Manitoulin Island in Ontario

Take a Closer Look: Aboriginal Cultural Experiences: National Guidelines

A self-assessment and reference tool, Aboriginal Cultural Experiences: National Guidelines, was developed to support the creation and expansion of Aboriginal cultural tourism in Canada. These guidelines were created through national consultation with the Aboriginal Tourism Marketing Circle partners and industry, with support from Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development Canada. The Aboriginal Tourism Association of Canada continues to provide guidance for Aboriginal communities and entrepreneurs, and the non-Aboriginal tourism industry, on standards. To read the guidelines, visit Aboriginal Cultural Experiences: National Guidelines[PDF] : www.aboriginalbc.com/assets/corporate/AboriginalCulturalExperiencesGuide_2013-s.pdf

For an in-depth exploration of a Canadian Aboriginal tourism destination, see the case study at the end of this chapter on the Trails of 1885 project. This and other initiatives have been successful across the country, including some in British Columbia, which has begun to emerge as a premier destination for Aboriginal experiences.

Aboriginal Tourism in BC

The Aboriginal Tourism Association of BC (AtBC) was founded in 1996, spurred by a research project that detailed the changing motivations of visitors to BC. It identified that specific target markets were particularly motivated to visit BC to experience local or regional Aboriginal culture. Using this information, AtBC created a work plan, established funding partnerships with governments, developed a membership model, and initiated a range of strategies and tactics outlined in two five-year plans.

Spotlight On: Aboriginal Tourism BC

BC’s tourism industry is fortunate to have an active organization like Aboriginal Tourism BC (AtBC) which, while young, has gained an international reputation for effectiveness. Its role is to encourage the professional development of Aboriginal cultural experiences in the province and to then market those businesses to the world. For more information, visit Aboriginal Tourism BC: www.aboriginalbc.com/corporate/

Since its inception, AtBC has grown to represent over 150 diverse stakeholder businesses, including campgrounds, art galleries and gift shops, hotels, eco-lodges and resorts, Aboriginal restaurants and catering services, cultural heritage sites and interpretive centres, kayak and canoe tours, adventure tourism operations, and guided hikes through heritage sites (Aboriginal Tourism BC, 2012). It has also proven adept at online promotion and social media. As well, it has become world renowned for its strategic approach to Aboriginal tourism development, which we examine in the next section.

Take a Closer Look: Aboriginal Tourism Promotion in BC (#AboriginalBC)

Visit Aboriginal Tourism Promotion in BC (www.aboriginalbc.com/media/) to see a promotional video that introduces BC Aboriginal culture to viewers around the world using the hashtag #AboriginalBC.

A Strategic Approach to Growth

In 2012, AtBC released its five-year strategic plan, which identified targets for Aboriginal cultural tourism industry success. Its goals by 2017 included (Aboriginal Tourism BC, 2012):

- Increased provincial revenue of $68 million (10% growth per year)

- Employment at 4,000 full-time equivalent positions (10% growth per year)

- 100 market-ready Aboriginal cultural tourism businesses (10% growth per year in all six BC tourism regions)

To achieve these targets, the plan identified key strategies, reviewed and adjusted annually, such as (Aboriginal Tourism BC, 2013):

- Push for market readiness

- Build and strengthen partnerships

- Focus on online marketing

- Focus on key and emerging markets

- Focus on authenticity and quality assurance

- Take a regional approach

Following good overall tourism planning principles, AtBC ensured its plan aligned with Destination BC’s five-year tourism strategy, Gaining the Edge, as well as Canada’s federal tourism strategy. As part of this alignment, recent efforts have placed renewed emphasis on the need for market readiness.

Push for Market Readiness

As we’ve learned elsewhere in this textbook, today’s travellers are more complex than in the past and have higher expectations. Potential guests are web-savvy and have the world at their fingertips. For this reason, it’s important that Aboriginal operators ensure they are sufficiently ready to run as a tourism business.

There are three categories of readiness, each with a set of criteria that must be met (Aboriginal Tourism Association of Canada, 2013):

- A visitor-ready operation is often a start-up or small operation that might qualify for a listing in a tourism directory but not be considered ready for cost-shared promotions with other businesses due to lack of amenities or predictability.

- A market-ready business must meet visitor-ready criteria plus demonstrate a number of other strengths around customer service, marketing materials, published pricing and payments policies, short response times and reservations systems, and so on.

- Export-ready criteria include the previous categories, plus sophisticated travel distribution trade channels to attract out-of-town visitors. They provide highly reliable services to all guests, particularly those travelling with groups.

By educating cultural tourism businesses about these standards, and then creating incentives for marketing opportunities, AtBC helps to raise the bar for BC Aboriginal cultural tourism experiences. Its goal is to push as many operators toward market readiness (the second category) as possible so that they may eventually become export ready alongside other BC tourism experiences.

Authenticity and Quality Assurance

Another one of the five-year strategic initiatives is the program to encourage visitors to purchase authentic arts and crafts, not unauthorized knock-offs. The Authentic Indigenous Artisan Program protects Aboriginal artists by identifying three tiers of artwork for active promotion (Authentic Indigenous, 2015):

- Tier 1: The highest level of authenticity. If an artist, or an artist via an indigenous company, designs, produces, and distributes an indigenous art product, it will be permitted to display a Tier 1 Authentic Indigenous stamp or tag. This tag ensures that indigenous artists and craftspeople have been remunerated for their work, while at the same time the integrity of their designs is being protected.

- Tier 2: Allows indigenous arts entrepreneurs to compete in a market where there has traditionally been no indigenous involvement. If an indigenous art product is designed by an indigenous person and distributed by an indigenous person or business, but made outside the indigenous community, it can display a Tier 2 Authentic Indigenous stamp or tag.

- Tier 3: Allows artists to license their creations for production and sale outside of the indigenous community.

Take a Closer Look: Authentic Indigenous

This website explains the authenticity program and provides detailed profiles of artists, samples of indigenous art products, and lists of indigenous sellers. Peruse beadwork, button blankets, carvings, weaving, ceramics, digital art, and textiles, and learn about the craftspeople who create them. Find out where you can purchase authentic products and explore the creation process including traditional methods of harvesting materials by visiting the Authentic Indigenous website: http://authenticindigenous.com

FirstHost

Another key component of the Aboriginal tourism experience is the host. In BC, the FirstHost program supports the development of Aboriginal hosts who are well trained, know what guests are looking for, and who can help provide an authentic cultural experience. This is a one-day tourism workshop offered through the Native Education College and delivered throughout the province and Canada.

FirstHost was inspired by Hawaiian tourism pioneer, Dr. George Kanahele (1913-2000), who saw the impact tourism was having on indigenous culture and set out to educate the industry that “the relationship between place, host and guest must be one of equality” (Native Education College, 2014, p. 28). Participants learn about hospitality service delivery and the special importance of the host, guest, and place relationship. The program is recognized by Aboriginal Tourism BC, WorldHost, and is funded by the Coastal Corridor Consortium of educators from multiple postsecondary institutions and cultural organizations (Native Education College, 2014). This well-received workshop, delivered by Aboriginal trainers, is another reason Aboriginal tourism continues to grow stronger in the province.

Examples of BC Aboriginal Tourism Development

Spotlight On: The Kamloopa PowWow

The Kamloopa PowWow, hosted each year by the Secwepemc Indian Band in Kamloops, draws over 20,000 visitors each year from BC, the rest of North America, and as far away as China, Germany, and Japan. Featuring songs, storytelling, dance, and other traditional cultural components, the event is one of the largest in Western Canada and represents a major tourism draw for the community. For more information, visit the Kamloopa PowWow website: www.tourismkamloops.com/kamloopa-powwow-in-kamloops-british-columbia

Aboriginal tourism in BC ranges from arts and cultural attractions to authentic food and beverage experiences to wildlife tours that highlight the spiritual significance of BC’s natural places to Aboriginal people.

Take a Closer Look: Aboriginal Experiences – a Journey

The consumer website for Aboriginal Tourism BC members features things to do, places to see, and a blog that details authentic experiences such as participating in a traditional sweat lodge. For more information, visit the Aboriginal Tourism BC website: www.aboriginalbc.com

Examples of BC Aboriginal tourism enterprises include:

- The Bill Reid Gallery of Northwest Coast Art in the heart of downtown Vancouver, home of the permanent collection of Bill Reid as well as contemporary exhibitions

- St. Eugene Golf Resort Casino, a First Nation-owned 4.5-star hotel with a golf course and casino, outside of Cranbrook in the Kootenay Rockies

- Cariboo Chilcotin Jetboat Adventures, offering exciting and scenic tours of the Fraser River

- Quw’utsun’ Cultural and Conference Centre, owned by the Cowichan band in Duncan

- Salmon n’ Bannock Bistro, offering authentic Aboriginal food in urban Vancouver

- The village of Ninstints (Nans Dins), a UNESCO world heritage site located on a small island off the west coast of Haida Gwaii

Take a Closer Look: UNESCO World Heritage List

This list, evolving from 1972 World Heritage Convention, identifies outstanding significant sites across the globe, linking the concepts of nature conservation and the preservation of cultural properties. The convention sets out the duties of governments in identifying potential sites and their role in protecting and preserving them. The list features an interactive map and an alphabetical list. To explore the more than 1,000 properties on the list, visit the UNESCO World Heritage List: http://whc.unesco.org/en/list

While AtBC members are too numerous to detail here, one BC community is often in the spotlight for its significant tourism activity, thanks to its physical and cultural assets and positive leadership. Let’s take a closer look at this example.

Nk’Mip

The Osoyoos (Nk’Mip) Indian Band (OIB) is part of the Okanagan First Nation located in the Interior of BC. The band is home to about 400 on-reserve members. A main goal of the OIB is to move from dependency to a sustainable economy like that which existed before contact (Centre for First Nations Governance, 2013).

Take a Closer Look: Centre for First Nations Governance Success Stories

The Centre for First Nations Governance is a non-profit organization dedicated to providing self-governance support to First Nations communities across Canada. It helps with planning, governance, the establishment of laws, and nation-rebuilding efforts. Its website features success stories, in video format, that highlight these efforts. For more information, visit the Centre for First Nations Governance Success Stories: http://fngovernance.org/success

Okanagan First Nations once travelled widely to fish, gather, and hunt. Each year, the first harvests of roots, berries, fish, and game were celebrated during ceremonies honouring the food chiefs who provided for the people. During the winter, people returned to permanent winter villages. The names of many of the settlements in the Okanagan Valley — Osoyoos, Keremeos, Penticton and Kelowna — come from Aboriginal words for these settled areas and attest to the long history of the Syilx people on this land.

Just 40 years ago, the OIB was bankrupt and living off government social assistance. In 1988, it sought to turn the tide on this history and created the Osoyoos Indian Band Development Corporation (OIBDC). Through good leadership and initiative, the band has been able to develop agriculture, eco-tourism, and commercial, industrial, and residential developments on its 32,200 acre reserve lands. It does have the good fortune to be located in one of Canada’s premier agricultural and tourism regions; however, it has also taken a determined and well-crafted effort to become an example of indigenous economic success. The band employs hundreds of people and has annual revenues of around $26 million (LinkBC, 2012).

The OIBDC now manages a number of tourism operations, and visitors to this sunny desert region can stay in the 226-room Spirit Ridge Vineyard Resort & Spa, visit the Nk’Mip Desert Cultural Centre, camp in the Nk’Mip Campground & RV Resort (a 326-site operation open year round), and enjoy visiting Nk’Mip Cellars (the first Aboriginal-owned winery in North America). Site preparation is also underway for a $120 million Canyon Desert Resort, a joint venture with Bellstar Hotels and Resorts located adjacent to the 18-hole Nk’Mip Canyon Desert Golf Course. Future vineyard and resort developments are on the drawing board (LinkBC, 2012).

The area attracts about 400,000 visitors per year, and at peak tourist season there is essentially full employment among the more than 470 members of the Osoyoos reserve. In addition to the core businesses, many secondary businesses have formed. For example, the award-winning Nk’Mip Desert Cultural Centre promotes conservation efforts for desert wildlife and has also helped to create several spinoff businesses, including a landscaping business, a greenhouse for indigenous plants, a website development business, and a community arts and crafts market (LinkBC, 2012).

Conclusion

Examples like Nk’Mip demonstrate that BC is on track to become one of the world’s leading destinations for Aboriginal tourism experiences. Across Canada, First Nations and their partners are using Aboriginal-developed standards to help preserve and strengthen cultures while building economic benefits for their communities. This is directly in line with the global trend toward linking tourism with the need to uphold indigenous rights. When developed in partnership with indigenous communities, Aboriginal tourism can continue to attract visitors, provide quality guest experiences, and honour Aboriginal heritage.

Up to this point, we’ve gained an understanding of multiple sectors of the industry as well as special considerations for professionals in BC. Chapter 13 explores careers and work experience in tourism and hospitality.

Key Terms

- Aboriginal cultural experiences: experiences that are offered in a manner that is appropriate, respectful, and true to the Aboriginal culture being portrayed

- Aboriginal cultural tourism: Aboriginal tourism that incorporates Aboriginal culture as a significant portion of the experience in a manner that is appropriate, respectful, and true (see Aboriginal cultural experiences)

- Aboriginal peoples: the indigenous people (see below) of Canada, recognized in the Canadian Constitution Act as comprising three groups: First Nations, Métis, and Inuit

- Aboriginal tourism: tourism businesses that are majority owned and operated by First Nations, Métis, and Inuit (known as indigenous tourism outside of Canada)

- Aboriginal Tourism Association BC (AtBC): the organization responsible for developing and marketing Aboriginal tourism experiences in BC in a strategic way; members are over 51% owned and operated by First Nations, Métis, and Inuit

- Aboriginal Tourism Association Canada (ATAC): a consortium of over 20 Aboriginal tourism industry organizations and government representatives from across Canada

- American Indian: a term used to describe First people in the United States, still used today

- Appropriation: the action of taking something for one’s own use, typically without the owner’s permission

- Authentic Indigenous Artisan Program: protects Aboriginal artists by identifying three tiers of artwork based on the degree to which Aboriginal people have participated in their creation; a tool to combat cultural appropriation

- Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous People: a 2007 statement that set forth the minimum standards for the survival, dignity, and well-being of the indigenous peoples of the world

- Eskimo: a term once used by non-Inuit people to describe Inuit people; no longer considered appropriate

- Export-ready criteria: the highest level of market readiness, with sophisticated travel distribution trade channels, to attract out-of-town visitors and highly reliable service standards, particularly with groups

- First Nation: one of the three recognized groups of Canada’s Aboriginal peoples (along with Inuit and Métis)

- FirstHost: an Aboriginal tourism workshop focusing on hospitality service delivery and the special importance of the host, guest, and place relationship

- Indian (or Native Indian): a legal term in Canada, once used to describe Aboriginal people but now considered inappropriate

- Indigenous peoples: groups specially protected in international or national legislation as having a set of specific rights based on their historical ties to a particular territory, and their cultural or historical distinctiveness from other populations

- Indigenous tourism: a synonym for Aboriginal tourism, the more commonly used term in BC (see above)

- Inuit: one of the three recognized groups of Canada’s Aboriginal peoples (along with First Nation and Métis), from the Arctic region of Canada

- Larrakia Declaration: a set of principles developed to guide appropriate indigenous tourism development

- Marae: a communal or sacred centre that serves a religious and social purpose in Polynesian societies

- Market-ready business: a business that goes beyond visitor readiness to demonstrate strengths in customer service, marketing, pricing and payments policies, response times and reservations systems, and so on

- Métis: one of the three recognized groups of Canada’s Aboriginal peoples (along with First Nation and Inuit), meaning “to mix”

- Visitor-ready business: often a start-up or small operation that might qualify for a listing in a tourism directory but is not ready for more complex promotions (like cooperative marketing); may not have a predictable business cycle or offerings

Exercises

- Reread the Larrakia Declaration mentioned earlier in this chapter. Find one statement that resonates with you either for personal reasons or as a future tourism professional. Why do you feel this principle is important?

- Why have the terms used to describe Aboriginal people changed over time? Why is it important for tourism professionals to respect these terms?

- Who are the local Aboriginal groups in your community? Are these First Nations, Métis, or Inuit? What are their languages called?

- Suggest three reasons why Aboriginal tourism is different from product-based subsectors of the industry (e.g., golf tourism, cuisine tourism).

- How many jobs did Aboriginal tourism generate in Canada in 2014? What is the goal for Aboriginal tourism jobs in BC for 2017? Why, in your opinion, is this a growth area?

- Are there Aboriginal tourism businesses in your area? Try to find at least two (you can use the Aboriginal BC website: (www.aboriginalbc.com) to locate them). How would you rate their market readiness? Give three reasons for your assessment.

- Complete online research to identify four international (non-US or Canada) indigenous tourism experiences/attractions. Create a table to record the following information:

- Indigenous group represented

- Ownership

- Products or services provided

- Years of operation

- Indigenous hosts

- Authenticity of experience

- Market readiness (based on website/marketing materials)

- Notable features

- Compare and contrast the experiences you summarized in question 7. Which businesses do you think are the most successful, and why? Which might be struggling? Which would you like to visit? Why or why not?

- What is the name of the program designed to help guests find authentic Aboriginal products? How does it help to combat appropriation? Describe the three tiers of the program, and visit the website to find examples of one product in each tier.

Case Study: Tourism and the Red Dzao and Black Hmong in Vietnam

In the mountainous region of northern Vietnam, ethnic minorities including the Red Dzao and Black Hmong once generated income through subsistence farming, timber harvesting, and opium cultivation. As tourism to the region increased, this also became an economic opportunity, one with the potential to benefit many people.

A number of developments, including a community-based tourism project supported by Capilano University and Hanoi Open University, and funded by the Pacific Asia Travel Association, increased tourism revenues coming into the community. The project began in the village of Ta Phin, and after some promising steps forward there, it was replicated in Lao Chai.

Lao Chai used to be just a lunch stop for tourists trekking through the beautiful region. Over a period of many years, training and capacity-building activities were undertaken by local indigenous people with the support of project volunteers. The fascinating culture, the hospitality of the community, and new trekking routes created a more complete tourism destination. Now the town is seen as a suitable place for an overnight stay.

A potential threat to the rights of the ethnic minorities and the village products has been the lack of inclusion and participation in decision making and tourism planning. This was evident during the development of Hoang Lien Son National Park. To protect this regional mountain range, authorities increased the borders of the park, encroaching on traditionally important natural resources for the village. Additional challenges arose because non-indigenous Vietnamese hold the majority of government positions and own the majority of tourism businesses in the region.

Despite these challenges, and with the support of students and faculty from Capilano University and Hanoi Open University, some indigenous people have set up small shops and a restaurant, which attract visitors interested in stopping for lunch. Homestays have been certified, allowing guests to enjoy an overnight experience in the village as part of an indigenous family. As these operations have proved successful, additional families have worked to train and make investments in their properties.

Watch the video at When a Village was Heard – Capilano U / PATA Foundation Tourism Project: www.youtube.com/watch?v=RSSPiHC4Ovc.

- What were some of the challenges to establishing tourism in the community?

- Review the Larrakia Declaration mentioned earlier in this chapter. What, in your opinion, are the most important of these principles that need to be understood in order for a project like this to succeed?

- Who were the stakeholders brought to the table by the development project?

- What changes were implemented? What support was offered to community members?

- Whose responsibility is the ongoing success of the project? How might success be measured?

- What are the lessons for Aboriginal tourism development in BC? List five strategies used or actions taken in Viet Nam that could be applied here at home.

Case Study: Trails of 1885 Bridges Cultures and Builds Tourism

Western Canada in the 1880s was facing a time of rapid change as the buffalo disappeared and the established way of life was rocked to its core. Tensions rose between European settlers and the Métis, whose rights had been eroded. In 1885, the North-West Resistance (formerly known as the North-West Rebellion) concluded with the hanging of resistance leader Louis Riel and eight other Aboriginal leaders (Trails of 1885, 2015).

In the years since, residents of Saskatchewan have protected areas from major interpretive centres to remote meadows and hillsides where solitary historic markers recount stories from an almost mythical past.

In 2006, a small group of tourism developers and historic site managers gathered in Saskatoon to discuss how these locations and their stories could be brought together and enhanced to collectively attract more visitors to the region.

As detailed in Cultural and Heritage Tourism: A Handbook for Community Champions, their project included:

- Creating an inventory of 1885-related sites and stories

- Meeting with site stakeholders to gauge interest in the project

- Acknowledging that First Nations and Métis stories had been previously overlooked

- Creating the 1885 coalition (Elders, accommodations, tourism organizations, tourism attractions, museums, tour operators)

- Reaching beyond Saskatchewan (the site of the main historical event) to Alberta and Manitoba sites related to the story of the North-West Resistance

- Finding funding, striking a steering committee, and finding a project manager

- Navigating culturally sensitive issues including the language of program delivery

- Creating visuals and branding (including the Trails of 1885 brand itself)

The project relied on the participation of various stakeholder groups and the leadership of a local champion. As a result of their efforts, an elk-hide proclamation was signed by First Nations, the Métis Nation, and federal and provincial governments.

Numerous other major events were held throughout the year including the first-ever reenactment of the Battle of Poundmaker Cree Nation and other 1885 ceremonies in communities across the region. The added impact of Trails of 1885 resulted in the largest attendance of the annual Métis homecoming festival (Back to Batoche Days).

To support long-term tourism benefits to the region, these activities were reinforced by capital projects such as highway improvements (to the sites), highway and site signage, large maps at various 1885 sites, and multi-million dollar improvements at Batoche. After this multi-year project, a new non-profit corporation, Trails of 1885 Association, was created to extend the work into the future and promote the region as a long-term tourism draw.

According to one of the initiative’s leaders, “the project has certainly met one of its main goals—to increase visitation and visitor satisfaction, while developing First Nations and Métis cultural awareness locally, regionally, provincially, and nationally” (LinkBC, 2012, p. 66).

Visit the site at www.trailsof1885.com and answer the following questions:

- List two attractions in each of the three provinces that span this project. What do they have in common?

- List five stakeholder groups who participated in the development of Trails of 1885. How might their interests differ? How might they align? Name three benefits of having these partners work together.

- What kind of tours are available to visitors wanting to learn more about this time in Canada’s history?

- Based on the website, where would you say the Trails of 1885 falls on the readiness scale (visitor ready, market ready, export ready)? Why would you classify it in this way?

- Go back to the Larrakia Declaration and create a checklist made up of the statements. In what ways did this project adhere to the principles set out in the declaration? Are there any ways the project could have done better?

References

Aboriginal Tourism Association BC & Canadian Tourism Human Resource Council (CTHRC). (2013). Aboriginal cultural tourism business planning guide. [PDF] Retrieved from http://linkbc.ca/siteFiles/85/files/ACTBPG.pdf

Aboriginal Tourism Association of Canada (as Aboriginal Tourism Marketing Circle). (2013). Aboriginal cultural tourism guide. [PDF] Retrieved from http://aboriginaltourismmarketingcircle.ca/wp-content/uploads/2014/01/AboriginalCulturalExperiencesGuide_2013-s.pdf

Aboriginal Tourism BC. (2012). The next phase (2012-2017): A five-year strategy for Aboriginal cultural tourism in BC. [PDF] Retrieved from www.aboriginalbc.com/assets/corporate/The%20Next%20Phase%20-%20BCs%20Aboriginal%20Cultural%20Tourism%20Strategy%20-%20AtBC.pdf

Aboriginal Tourism BC. (2013). The next phase (2012-2017): A five-year strategy for Aboriginal cultural tourism in BC: Year one report. [PDF] Retrieved from www.aboriginalbc.com/assets/AtBC-5-Year-Plan-2012-2017-The-Next-Phase-Year-1-Keith-Henry.pdf

Authentic Indigenous. (2015). Authenticity tags. Retrieved from http://authenticindigenous.com/authenticity-tags/

Centre for First Nations Governance. (2013). Best practices: Osoyoos Indian Band. Retrieved from http://fngovernance.org/toolkit/best_practice/osoyoos_indian_band

Coates, Ken S. (2004). A global history of indigenous peoples: Struggle and survival. New York, NY: Palgrave MacMillan. p12 ISBN 0-333-92150-X.

Kanahele, G. (1991). Critical reflections on cultural values and hotel management in Hawai’i. Project Tourism Keeper of the Culture. Honolulu, HI: The WAIAHA Foundation.

LinkBC, Federal Provincial Territorial Minsters of Culture and Heritage. (2012). Cultural & heritage tourism: A handbook for community champions. [PDF] Retrieved from http://linkbc.ca/siteFiles/85/files/CHT_WEB.pdf

Native Education College. (2014). First Host: Offering hospitality skills like nobody else.[PDF] Sample Workbook. Retrieved from www.necvancouver.org/sites/default/files/firsthost_2014_sample.pdf

New Zealand Maori Tourism Society. (2012). Maori tourism. Retrieved from www.maoritourism.net

O’Neil, B., Payer, B., Williams, P., Morten, K., Kunin, R., & Gan, L. (2014). National Aboriginal tourism research project 2014. Vancouver, BC: Aboriginal Tourism Marketing Circle.

Pacific Asia Travel Association (PATA) and World Indigenous Tourism Alliance (WINTA). (2014). Indigenous Tourism and human rights in Asia and Pacific Region: Review, analysis & guidelines. Bangkok, Thailand: PATA.

Trails of 1885. (2015). Home page. Retrieved from www.trailsof1885.com.

United Nations. (2007). UN declaration on the rights of indigenous people. [PDF] www.un.org/esa/socdev/unpfii/documents/DRIPS_en.pdf

Wilson, K. & Henderson, J. (2014, March 3). First Peoples: A guide for newcomers. [PDF] Vancouver: City of Vancouver. Retrieved from http://vancouver.ca/files/cov/First-Peoples-A-Guide-for-Newcomers.pdf

World Indigenous Tourism Alliance. (2012). Larrakia declaration on indigenous tourism. [PDF] www.winta.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/08/The-Larrakia-Declaration.pdf

WWF International Arctic Programme. (n.d.). Code of conduct for Arctic tourists. [PDF] Retrieved from www.panda.org/downloads/arctic/codeofconductforarctictourists(eng).pdf

Attributions

Figure 12.1 Haida Bird by Doug is used under a CC-BY-NC-ND 2.0 license.

Figure 12.2 We Don’t Climb by Steel Wool is used under a CC-BY-NC-ND 2.0 license.

Figure 12.3 First Nations performers during the opening ceremony by Province of BC is used under a CC BY-NC-SA 2.0 license.

Figure 12.4 Animal and ‘native’ cultural products by Toban B is used under a CC-BY-NC 2.0 license.

Figure 12.5 Cover of the Aboriginal Cultural Tourism Business Planning Guide by LinkBC is used under a CC-BY-NC-ND 2.0 license.

Figure 12.6 head smashed in buffalo jump by Roland Tanglao is used under a CC-BY 2.0 license.

Figure 12.7 Authentic Indigenous Logo by LinkBC is used under a CC-BY-NC-ND 2.0 license.

Figure 12.8 FirstHost Cover by LinkBC is used under a CC-BY-NC 2.0 license.

Figure 12.9 killer whale in the foreground by Neil Banas is used under a CC-BY-NC 2.0 license.

Figure 12.10 Osooyos by LinkBC is used under a CC-BY-NC 2.0 license.

Figure 12.11 Cranbrook by Province of British Columbia is used under a CC-BY-NC-ND 2.0 license.