9.3 Crime and the Law

Learning Outcomes

By the end of this chapter, you’ll be able to:

- Identify and differentiate between different types of crimes.

- Distinguish three different measures of crime statistics.

- Explain the falling rate of crime in Canada.

- Examine the overrepresentation of different minorities in the corrections system in Canada.

- Discuss alternatives to prison.

What is Crime?

Although deviance is a violation of social norms, it is not always punishable, and it is not necessarily bad. Crime, on the other hand, is a behaviour that violates official law and is punishable through formal sanctions. Walking to class backwards is a deviant behaviour. Driving with a blood alcohol percentage over the province’s limit is a crime. Like other forms of deviance, however, ambiguity exists concerning what constitutes a crime and whether all crimes are, in fact, “bad” and deserve punishment.

For example, in 1946 Viola Desmond refused to sit in the balcony designated for blacks at a cinema in New Glasgow, Nova Scotia, where she was unable to see the screen. She was dragged from the cinema by two men who injured her knee, and she was then arrested, obliged to stay overnight in the male cell block, tried without counsel, and fined.

The court ruling ended up ignoring the laws concerning racial segregation in Canada, which was the reason why she was removed from the cinema. Instead, her crime was determined to be tax evasion because she had not paid the 1 cent difference in tax between a balcony ticket and a main floor ticket. She took her case to the Supreme Court of Nova Scotia where she lost. In hindsight, and long after her death, she was posthumously pardoned, because the application of the law was clearly in violation of norms of social equality.

As noted above, all societies have informal and formal ways of maintaining social control. Within these systems of norms, societies have legal codes that maintain formal social control through laws, which are rules adopted and enforced by a political authority. Those who violate these rules incur negative formal sanctions in the form of fines, jail or court ordered retribution. Normally, punishments are relative to the degree of the crime and the importance to society of the value underlying the law. There are, however, other factors that influence criminal sentencing.

Types of Crimes

Not all crimes are given equal weight. Society generally socializes its members to view certain crimes as more severe than others. As discussed earlier, John Hagen distinguished between serious consensus crimes, like murder and sexual assault, about which there is near-unanimous public agreement, and conflict crimes, like prostitution or recreational drugs, which may be illegal but about which there is considerable public disagreement concerning their seriousness. Even within the category of crimes on which there is consensus, there is disagreement about levels of seriousness and punishment. For example, most people would consider murdering someone to be far worse than stealing a wallet and would expect a murderer to be punished more severely than a thief. In modern North American society, crimes are typically classified as one of two types based on their severity. Violent crimes (also known as “crimes against a person”) are based on the use of force or the threat of force. Rape, murder, and armed robbery fall under this category. Nonviolent crimes involve the destruction or theft of property, but do not use force or the threat of force. Because of this, they are also sometimes called “property crimes.” Larceny, car theft, and vandalism are all types of nonviolent crimes. If you use a crowbar to break into a car, you are committing a nonviolent crime; if you mug someone with the crowbar, you are committing a violent crime.

As noted earlier in the section on critical sociological approaches, when people think of violent and non-violent crime, they often picture street crime, or offenses committed by ordinary people against other people or organizations, usually in public spaces. An often-overlooked category of non-violent crime is corporate crime (or “suite crime”), crime committed by white-collar workers in a business environment. Embezzlement, insider trading, ponzi schemes and fraud are all types of corporate crime. Although these types of offences rarely receive the same amount of media coverage as street crimes, they can be far more damaging. The 2008 world economic recession was the ultimate result of a financial collapse triggered by corporate crime. An often-debated third type of crime is victimless crime. These are called victimless because the perpetrator is not explicitly harming another person. As opposed to battery or theft, which clearly have a victim, a crime like drinking a beer at age 17 or selling a sexual act do not result in injury to anyone other than the individual who engages in them, although they are illegal. While some claim acts like these are victimless, others argue that they actually do harm society. Prostitution may foster abuse toward women by clients or pimps. Drug use may increase the likelihood of employee absences. Such debates highlight how the interpretation of the deviant and criminal nature of actions develops through ongoing public discussion.

The Declining Crime Rate in Canada

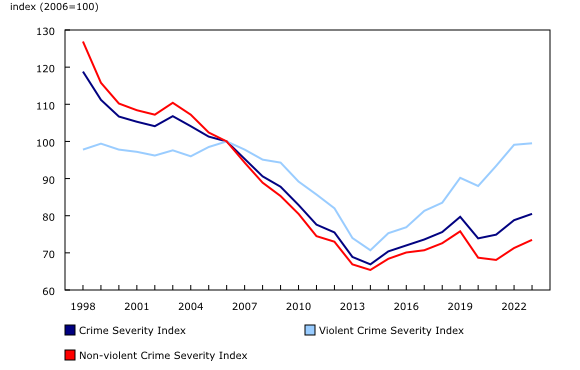

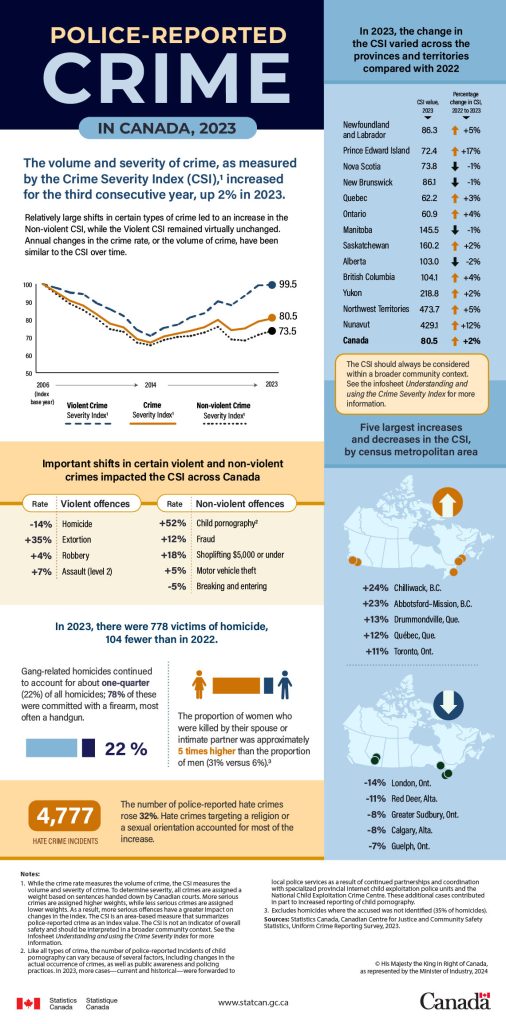

Crime rates were on the rise after 1960 but following an all-time high in the 1980s and 1990s, rates of violent and nonviolent crimes started to decline. Since 2012, crime rates have increased slightly. In 2019, there were over 2.2 million police-reported Criminal Code incidents (not including traffic violations), about 164,700 more incidents than in 2018. At 5,874 incidents per 100,000 population, the police-reported crime rate—which measures the volume of crime—increased 7% in 2019. This rate, however, was still 9% lower than a decade earlier in 2009 (Moreau, Jaffray and Armstrong, 2020). This trend has continued and the volume and severity of police-reported crime in Canada, as measured by the Crime Severity Index (CSI), increased by 2% in 2023 (Statistics Canada, 2024a). Non-violent crimes such as fraud (+12%), shoplifting (+18%) and car theft (+5%) increased, while crimes such as breaking and entering decreased. Violent crimes, on the other hand, such as homicide (-14%) decreased while robbery (+4%) and assault with a weapon or causing bodily harm (+7%) increased (Statistics Canada, 2024a).

What accounts for the general decreases in the crime rate since the early 1990s? During the period of lowest crime rates, opinion polls showed that a majority of Canadians believed that crime rates, especially violent crime rates, were rising (Edmiston, 2012), even though the statistics showed a steady decline since 1991. Where is the disconnect? There are three primary reasons for the decline in the crime rate. Firstly, it reflects the demographic changes to the Canadian population. The post-war baby boom continued into the early 1960s, but the birth rate fell afterwards and has remained low since the 1970s. As most crime is committed by people aged 18 to 34 and this age cohort has declined in size since 1991, it makes sense statistically that the crime rate has fallen. Property crimes, which are predominantly associated with teenagers and young adults, leveled off during the 80’s, while violent crimes, associated with teenagers and young adults but also middle-aged adults, decreased in the 90s. The number of people aged 20 to 34 dropped by 18% Canada between 1990 and 1999 (Ouimet, 2004).

Secondly, male unemployment is highly correlated with the crime rate, especially property crimes. Unemployment rates were high in the 1980s and again in the early 1990s, correlating with trends in property crime (Pottie Bunge, Johnson and Baldé, 2005). Following the recession of 1990–1991, better economic conditions improved male unemployment. The total unemployment rate dropped by 27% in Canada between 1991 and 1999, meaning that the economic situation for young adults improved (Oimet, 2004).

Thirdly, police methods have arguably improved since 1991, including having a more targeted approach to particular sites and types of crime. Strategies such as “hot-spot policing” and “focused deterrence,” as well as collaboration with non-police organizations such as private security, neighbourhood watch programs, local health professionals, community and municipal groups, and other government organizations have proven effective (Council of Canadian Academies, 2014). Similarly, the shift to community policing and a more problem solving rather than reactive approaches improves relationships between police and citizens and lowers crime rates (Pottie Bunge, Johnson and Baldé, 2005).

Corrections

The corrections system, more commonly known as the prison system, is tasked with supervising individuals who have been arrested, convicted, and sentenced for a criminal offence. At the end of 2023, approximately 22,000 adults were in prison in Canada, while another 71,000 were under community supervision or probation (Statistics Canada, 2025a).

Average counts of adults in provincial and territorial correctional programs

Persons

| Custodial and community supervision | 2018 / 2019 | 2019 / 2020 | 2020 / 2021 | 2021 / 2022 | 2022 / 2023 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total actual-in count | 23,783.2 | 23,894.1 | 18,950.2 | 20,438.5 | 22,318.5 |

| Sentenced, actual-in count | 8,708.2 | 7,946.7 | 5,881.2 | 5,798.3 | 5,915.7 |

| Remand, actual-in count | 14,778.4 | 15,505.3 | 12,752.5 | 14,414.5 | 16,193.9 |

| Other statuses, actual-in count | 296.6 | 442.1 | 316.5 | 225.7 | 208.9 |

| On-register count | 25,476.4 | 25,563.8 | 19,804.3 | 21,152.3 | 22,945.6 |

Rate

| Incarceration rates per 100,000 adults8 | 79.57 | 78.66 | 61.56 | 66.84 | 71.59 |

|---|

Persons

| Custodial and community supervision | 2018 / 2019 | 2019 / 2020 | 2020 / 2021 | 2021 / 2022 | 2022 / 2023 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total community supervision count | 89,838.3 | 86,620.6 | 70,906.4 | 68,792.8 | 71,628.6 |

| Probation, community supervision | 82,499.9 | 79,652.3 | 64,970.8 | 60,993.9 | 62,789.7 |

| Conditional sentence, community supervision | 6,082.1 | 5,995.5 | 5,245.6 | 7,150.4 | 8,181.3 |

| Provincial parole, community supervision | 1,256.3 | 972.8 | 690.0 | 648.5 | 657.7 |

Rate

| Probation rates per 100,000 adults14 | 294.42 | 279.52 | 224.94 | 209.78 | 212.78 |

|---|

Source: Statistics Canada

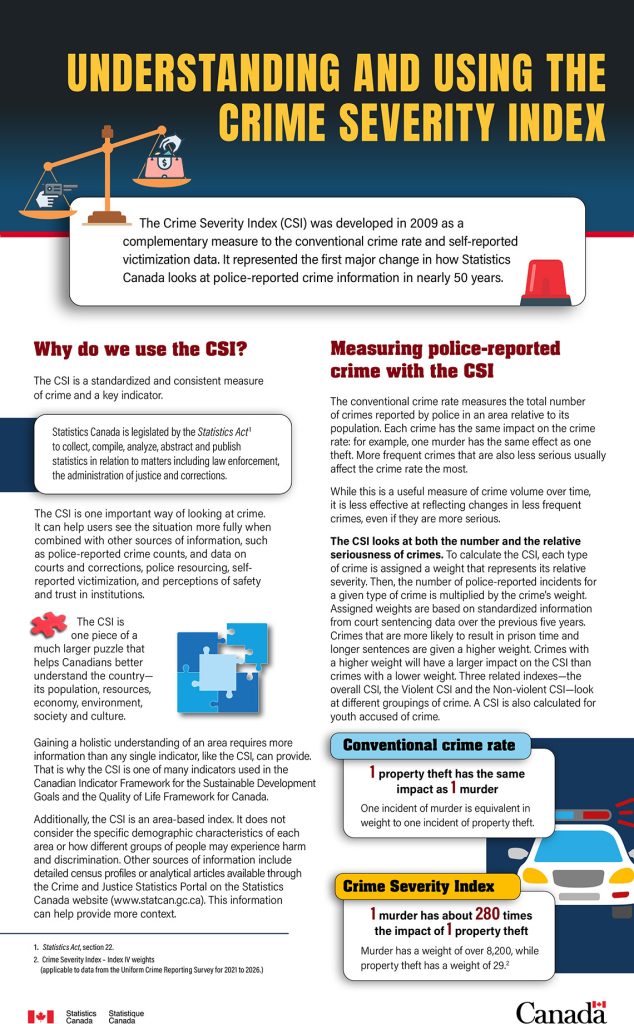

Understanding and Using the Crime Severity Index

The Crime Severity Index (CSI) was created in 2009 as a complimentary measure to conventional crime rate data and self-reported victimization data. It is a standardized and consistent measure and can be used as one key indicator when looking at crime. The conventional crime rate is calculated by adding up the number of crimes reported by the police over a period of time and geographical area, which is then divided by the population count for that area (Statistics Canada, 2024c). However, the CSI uses a different formula to calculate the severity of crime. To calculate the CSI, each type of crime is assigned a weight that represents its relative severity. Afterwards, the number of police reported incidents for a given type of crime is multiplied by the crime’s weight. Generally, crimes that are more likely to result in prison time and longer sentences are given a higher weight. For example, using the CSI, murder has a weight of over 2800, whereas property theft has a weight of 29 (Statistics Canada, 2024c). Therefore, the impact of one murder on the CSI is approximately 280 times greater than one property theft, whereas using the conventional crime rate property theft and murder are equally weighted. It is important to note that the CSI is a measure of crime reported by police for a particular geographic region. Unreported crimes are not included in the CSI measure and other factors such as the specific demographics of each area or how different groups experience harm (Statistics Canada, 2024c).

Incarceration Rates by Demographics

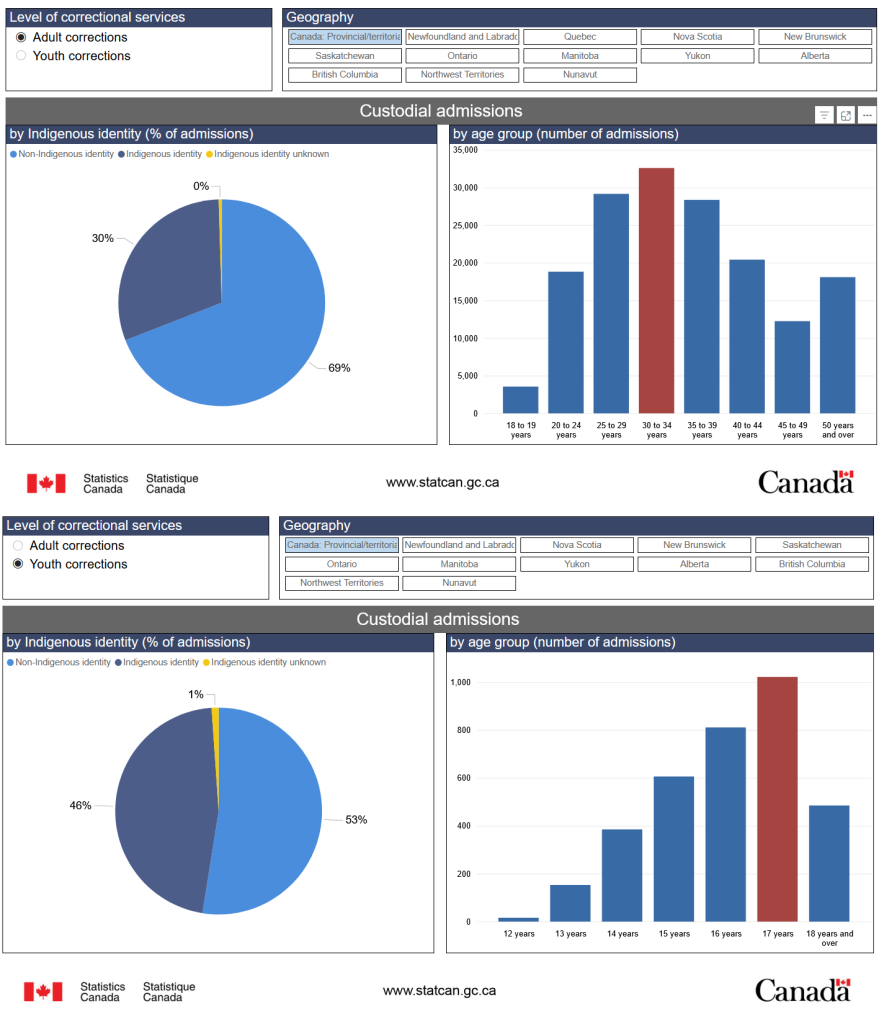

Incarceration rates vary and patterns can be identified by age, gender and race. Custodial admissions peak at approximately 30 years of age among adults and 17 years of age among youth.

Men area also more likely to be incarcerated than women. Women represent only a small proportion of those accused of police-reported crime and the tend to be convicted of less serious crimes than men. More violent crimes tend to be committed in the context of family violence or intimate partner violence (e.g., protecting children) (Government of Canada, 2024).

Indigenous Canadians are also more likely to be incarcerated than the non-Indigenous population. While Indigenous people accounted for about 5 per cent of the Canadian population, in 2023, they made up 28% per cent of the federal penitentiary population. Indigenous women made up 50 per cent of incarcerated women in Canada (Government of Canada, 2023). This problem of overrepresentation of Indigenous people in the corrections system — the difference between the proportion of Indigenous people incarcerated in Canadian correctional facilities and their proportion in the general population — continues to grow appreciably despite a Supreme Court ruling in 1999 (R. vs. Gladue) that the social history of Indigenous offenders should be considered in sentencing. Section 718.2 of the Criminal Code states, “all available sanctions other than imprisonment that are reasonable in the circumstances should be considered for all offenders, with particular attention to the circumstances of Aboriginal offenders.” (Correctional Investigator Canada, 2013).

Hartnagel (2004) summarised the literature on why Indigenous people are overrepresented in the criminal justice system. Firstly, Indigenous people are disproportionately poor, and poverty is associated with higher arrest and incarceration rates. Unemployment in particular is correlated with higher crime rates. Secondly, Indigenous lawbreakers tend to commit more detectable street crimes than the less detectable white collar or suite crimes of other segments of the population. Thirdly, the population of Indigenous people are younger than the average population. If people ‘age out’ of crime, groups that are on average younger may have higher arrest or incarceration rates, while we would expect that groups that are older will have lower rates. Not only are factors associated with Hirschi’s Control Theory at play, but theories that point to the relationship between impulsivity (e.g., failure to comprehend longer term impacts) and offending within adolescence and emerging adulthood that declines as people mature (e.g., Ray & Jones, 2023).

Prison and their Alternatives

Recent public debates in Canada on being “tough on crime” often revolve around the idea that imprisonment and mandatory minimum sentences are effective crime control practices. It seems intuitive that harsher penalties will deter offenders from committing more crimes after their release from prison. However, research shows that punitive “tough on crime” policies do not reduce crime rates (Pottie Bunge, Johnson & Baldé, 2005; Pratt & Cullen, 2005). Nor does serving prison time reduce the propensity to re-offend after the sentence has been completed. In general, the effect of imprisonment on recidivism — the likelihood for people to be arrested again after an initial arrest — was either non-existent or actually increased the likelihood of re-offence in comparison to non-prison sentences (Nagin, Cullen, & Jonson, 2009). In particular, first-time offenders who are sent to prison have higher rates of recidivism than similar offenders sentenced to community service (Nieuwbeerta, Nagin, & Blockland, 2009).

Moreover, the collateral effects of the imprisonment of one family member include negative impacts on the other family members and communities, including increased aggressiveness of young sons (Wildeman, 2010) and increased likelihood that the children of incarcerated fathers will commit offences as adults (van de Rakt & Nieuwbeerta, 2012). As noted above, some researchers have spoken about a penal-welfare complex to describe the creation of inter-generational criminalized populations who are excluded from participating in society or holding regular jobs on a semi-permanent basis (Garland, 1985). The painful irony for these groups is that the petty crimes like theft, public consumption of alcohol, drug use, etc. that enable them to get by in the absence of regular sources of security and income are increasingly targeted by zero tolerance and minimum sentencing policies of crime control.

There are a number of alternatives to prison sentences used as criminal sanctions in Canada including fines, electronic monitoring, probation, and community service. These alternatives divert offenders from forms of penal social control, largely on the basis of principles drawn from labelling theory. They emphasize to varying degrees compensatory social control, which obliges an offender to pay a victim to compensate for a harm committed; therapeutic social control, which involves the use of therapy to return individuals to a normal state; and conciliatory social control, which reconciles the parties of a dispute to mutually restore harmony to a social relationship that has been damaged.

Many non-custodial sentences involve community-based sentencing, in which offenders serve a conditional sentence in the community, usually by performing some sort of community service. The argument for these types of programs is that rehabilitation is more effective if the offender is in the community rather than prison. A version of community-based sentencing is restorative justice conferencing, which focuses on establishing a direct, face-to-face connection between the offender and the victim. The offender is obliged to make restitution to the victim, thus “restoring” a situation of justice. Part of the process of restorative justice is to bring the offender to a position in which they can fully acknowledge responsibility for the offence, express remorse, and make a meaningful apology to the victim (Department of Justice, 2013).

In special cases where the parties agree, Aboriginal sentencing circles involve victims, the Aboriginal community, and Aboriginal elders in a process of deliberation with Aboriginal offenders to determine the best way to find healing for the harm done to victims and communities. The emphasis is on forms of traditional Aboriginal justice, which center on healing and building community rather than retribution. These might involve specialized counseling or treatment programs, community service under the supervision of elders, or the use of an Aboriginal nation’s traditional penalties (Aboriginal Justice Directorate, 2005).

It is difficult to find data in Canada on the effectiveness of these types of programs. However, a large meta-analysis study that examined ten studies from Europe, North America, and Australia was able to determine that restorative justice conferencing was effective in reducing rates of recidivism and in reducing costs to the criminal justice system (Strang et al., 2013). The authors suggest that recidivism was reduced between 7 and 45 per cent from traditional penal sentences by using restorative justice conferencing.

Rehabilitation and recidivism are of course not the only goals of the corrections systems. Many people are skeptical about the capacity of offenders to be rehabilitated and see criminal sanctions more importantly as a means of (a) deterrence to prevent crimes, (b) retribution or revenge to address harms to victims and communities, or (c) incapacitation to remove dangerous individuals from society.

Media Attributions

- Gavel © Katrin Bolovtsova used under license via Pexels.

- Viola Desmond © Winnipeg Free Press is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Police-reported Crime Severity Indexes, 1998 to 2023 © Statistics Canada

- Crime 2023 Infographic © Statistics Canda

- Infosheet: Understanding and using the Crime Severity Index © Statistics Canada

- Correctional services statistics © Statistics Canada