2.4 Indigenous Children, Youth, and Families

“To heal a nation, we must first heal the individuals, the families and the communities.” – Art Solomon, an Anishinaabe elder

The Impact of Colonial History on Indigenous Peoples

Indigenous colonization can be described as the action or process of settling among and establishing control over the Indigenous People of an area. As the National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls (2019) notes, “Canada is a settler colonial country. European nations, followed by the new government of ‘Canada,’ imposed its own laws, institutions, and cultures on Indigenous Peoples while occupying their lands. Racist colonial attitudes justified Canada’s policies of assimilation, which sought to eliminate First Nations, Inuit, and Métis Peoples as distinct Peoples and communities” (National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls, 2019, p. 4).

According to the Best Start Resource Centre (2012), “Prior to colonization, sacred teachings were ways of life, passed along orally and through lived experience” (p. 7). Elders in Indigenous communities taught people about their place and relationship to the universe and each other: “Indigenous knowledges are conveyed formally and informally among kin groups and communities through social encounters, oral traditions, ritual practices, and other activities” (Bruchac, 2014, p. 1). This traditional knowledge, which “can be defined as a network of knowledges, beliefs, and traditions intended to preserve, communicate, and contextualize Indigenous relationships,” has been placed under continuous threat because of colonization (Bruchac, 2014, p. 2).

For more than 150 years, Indigenous children were taken from their families and communities to attend residential schools, often located very far from their homes. According to the National Centre for Truth and Reconciliation (n.d.), “more than 150,000 children attended Indian Residential schools. Many never returned” (para. 1). The negative effects of residential schools were passed from generation to generation. Indigenous Peoples have been working hard to overcome the legacy of residential schools and to change the realities for themselves, their families, and their Nations. By ending the silences under which Indigenous Peoples have suffered for many decades, the Truth and Reconciliation Commission opened the possibility that we may all come to see each other and our different histories more clearly and work together in a better way to resolve issues that have long divided us. It is the beginning of a new kind of hope rooted in the belief that telling the truth about our common history gives us a much better starting point in building a better future (Wilson, 2018).

In the video “Colonization” by Werklund School of Education (2018), Indigenous knowledge keepers Reg Crowshoe and Kerrie Moore share their wisdom and experiences about the impacts of colonization, including residential schools, on Indigenous Peoples:

To access a transcript for this video, please click Watch on YouTube.

Whether you come from the perspective of an Indigenous or non-Indigenous person, it is important to understand the impacts of colonial history. For the Indigenous person, learning about colonial history creates feelings of hurt, anger, and possibly shame. For the non-Indigenous person, learning about this history can lead to feelings of remorse and guilt. Some people, whether Indigenous or not, might say that colonization was a thing of the past and prefer to forget about this colonial history. The Calls to Action from the Truth and Reconciliation Commission recommend that Canadians move towards reconciliation of this colonial history. This reconciliation involves learning about colonial history—the true history, not the history that has been presented in history books. It is about re-writing the history from an Indigenous perspective. It is about creating a new beginning in Indigenous/non-Indigenous relations and “re-storying” that colonial history as a step towards reconciliation (Manitowabi, n.d.).

A history of colonization exists and persists all around us. This history is not your fault, but it is absolutely your responsibility. In the TEDx Talk, “Decolonization is for Everyone,” Nikki Sanchez (2019) discusses what colonization looks like and how it can be addressed by everyday people through decolonization. An equitable and just future depends on the courage we show today. After you finish watching the video, try to formulate one action that you can take in your life today to work towards decolonization.

To access a transcript for this video, please click Watch on YouTube.

The impacts of colonial history on Indigenous peoples in Canada have been significant. Strategic attempts to assimilate Indigenous peoples through colonial policies have resulted in many losses, including land and strong connections with Indigenous People’s language, culture, and traditional ways of knowing and being. The impact of these policies is evident through inter-generational traumas experienced by Indigenous Peoples across Canada. To engage in reconciliation, we must understand how colonization has impacted these communities’ traditions, their institutions, and their practices (Cull et al., 2018).

Indigenous Ways of Knowing, Being and Doing

The Seven Grandfather Teachings

According to Benton-Banai, as cited in Manitowabi (n.d.), the Seven Grandfather Teachings “form the foundation of an Indigenous way of life” and are the basis of sharing and respect (para. 1). Several versions of the Seven Grandfather Teachings exist; this abbreviation of Benton-Banai’s version is by Susan Manitowabi (n.d.):

The Creator gave the seven grandfathers the responsibility to watch over the people. In this recounting of the story, the seven grandfathers, seeing that the people were living a hard life, sent a messenger down to the earth to find someone who could tell what Ojibway life should be and bring him back. The messenger searched all directions—North, South, West and East—but could not find anyone. Finally, on the seventh try, the messenger found a baby and brought him back to where the grandfathers were sitting in a circle. The grandfathers, happy with the messenger’s choice, instructed him to take him all around the earth so the baby could learn how the Ojibway should lead their lives. They were gone for seven years. Upon his return, as a young man, the grandfathers, recognizing the boy’s honesty, gave him seven teachings that he could take with him. They are as follows: . . .

Nibwaakaawin—Wisdom: Wisdom, a gift from the Creator, is to be used for the good of the people. The term “wisdom” can also be interpreted to mean “prudence” or “intelligence.” This means that we must use good judgement or common sense when dealing with important matters. We need to consider how our actions will affect the next seven generations. Wisdom is sometimes equated with intelligence. Intelligence develops over time. We seek out the guidance of our Elders because we perceive them to be intelligent; in other words, they have the ability to draw on their knowledge and life skills in order to provide guidance.

Zaagi’idiwin—Love: Love is one of the greatest teachers. It is one of the hardest teachings to demonstrate, especially if we are hurt. Benton-Banai (1988) states . . . , “To know Love is to know peace.” Being able to demonstrate love means that we must first love ourselves before we can show love to someone else. Love is unconditional; it must be given freely. Those who are able to demonstrate love in this way are at peace with themselves. When we give love freely it comes back to us. In this way love is mutual and reciprocal.

Minaadendamowin—Respect: One of the teachings around respect is that in order to have respect from someone or something, we must get to know that other entity at a deeper level. When we meet someone for the first time, we form an impression of them. That first impression is not based on respect. Respect develops when one takes the time to establish a deeper relationship with the other. This concept of respect extends to all of creation. Again, like love, respect is mutual and reciprocal—in order to receive respect, one must give respect.

Aakode’ewin—Bravery: Benton-Banai (1988) states that “Bravery is to face the foe with integrity.” This simply means that we need to be brave in order to do the right thing, even if the consequences are unpleasant. It is easy to turn a blind eye when we see something that is not right. It is harder to speak up and address concerns for fear of being retaliated against. Oftentimes, one does not want to “rock the boat.” It takes moral courage to be able to stand up for those things that are not right.

Gwayakwaadiziwin—Honesty: It takes bravery to be honest in our words and actions. One needs to be honest first and foremost with oneself. Practicing honesty with oneself makes it easier to be honest with others.

Dabaadendiziwin—Humility: As Indigenous people we understand our relationship to all of creation. Humility is to know your place within Creation and to know that all forms of life are equally important. We need to show compassion (care and concern) for all of creation.

Debwewin—Truth: “Truth is to know all of these things” (Benton-Banai, 1988). All of these teachings go hand in hand. For example, to have wisdom, one must demonstrate love, respect, bravery, honesty, humility and truth. You are not being honest with yourself if you use only one or two of these teachings. Leaving out even one of these teachings means that one is not embracing the teachings. We must always speak from a truthful place. It is important not to deceive yourself or others.

Just as the boy was instructed to learn these teachings and to share them with all the people, we also need to share these teachings and demonstrate how to live that good, healthy life by following the seven grandfather teachings.

The Medicine Wheel

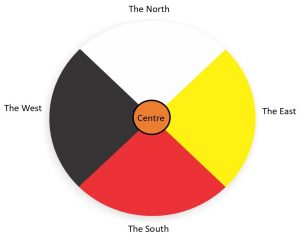

There are many versions of medicine wheel teachings and they vary from community to community, but there are some foundational concepts that are common to most. Hart and Nabigon describe the medicine wheel as an ancient symbol conceptualized as a circle divided into four quadrants/directions; each of these quadrants contains teachings about how we should live our lives, and about the need to balance all four aspects of the being—mental, emotional, physical, and spiritual (as cited in Manitowabi, n.d.). The medicine wheel reminds us that everything comes in fours: the four seasons, the four stages of life, the four races of humanity, four cardinal directions, etc.

The following is an synopsis of the medicine wheel teachings provided by Lillian Pitawanakwat-Ba from Whitefish River First Nation (as cited in Manitowabi, n.d.):

The Center: Represents the fire within and our responsibility for maintaining that fire. Pitawanakwat recalls that as a child, her father would ask at the end of the day, “My daughter, how is your fire burning?” In recalling the events of the day, she would reflect on whether she had been offensive to anyone, or whether or not she had been offended. This was an important part of nurturing the fire within as children were taught to let go of any distractions of the day and make peace within ourselves in order to nurture and maintain that inner fire. It is also a reminder that you need to maintain balance in all areas.

The East (Waabinong): According to Pitawanakwat, the springtime, and the spring of life are represented in the east. All life begins in the east; we begin our human life as we journey from the spirit world into this physical world. The teachings from the east remind us that all life is spirit (the wind, earth, fire, and water—all those things that are alive with energy and movement) and that to honour that life, we offer tobacco in thanksgiving. Prayers of thanksgiving honour all those things that we cannot exist without, for the breath of life, the cycles of time and to be grateful for life [sic]. We are especially grateful for natural law. All our teachings come from the natural world around us.

The South (Zhawanong): The summer and youth are represented in the southern direction. Summer is a time of continued nurturance. Youth are at a stage in life where they are no longer children and are not quite adults. They may be searching for what they had to leave behind in their childhood and struggling with their identity. In this direction, we are reminded to look after our spirits by finding that balance within ourselves and to pay attention to what our spirit is telling us. If we listen to our intuition, then the spirit will help to keep us safe. Youth who grow up without spirit nurturance have no direction and are at risk of being exposed to all kinds of dangers and distractions; their spirits have not been nurtured. Youth need nurturance, guidance and protection to help them through this transitional phase of their lives.

The West (Epangishmok): The western direction represents the adult stage of life. Death is also represented in this direction. Death comes in many forms – the end of our physical journey and crossing back into the spirit world; the setting sun and end of the day; or recognition that as old thoughts and feelings die, new ones emerge. The heart is also represented in the west. The heart helps us to evaluate, appreciate and enjoy our lives. By nurturing our hearts, we create balance in our lives.

The North (Kiiwedinong): The teachings of the north remind us to slow down and rest. The north is referred to as the rest period, a time to be respectful of the need to care for and nurture the physical body. It is also referred to by some as a period of remembrance—a time for contemplation of what has happened in life. Winter is represented in the north—it is a time for rest for the earth. It is also a time of reflection—on being a child, a youth and an adult. Elders, pipe carriers and the lodge keepers, reside in the north. Their teachings help us to embrace all aspects of our beings so that we can feel and experience the fullness of life. Wisdom also resides in the north. Elder’s share their stories in the winter months.

Learn more about the teachings shared by Lillian Pitawanakwat-ba of Whitefish River First Nation by visiting Four Directions Teachings (this link opens on a new page).

Ways to Recognize and Utilize an Indigenous Worldview in Child and Youth Care

On your journey of decolonization and Indigenization, it is helpful to self-assess your own intentions and behaviours in your present position as a post-secondary student. The Indigenized integral professional competency self-assessment is a tool you can use to identify your strengths and areas for development in working with Indigenous students and communities.

Indigenization, for this purpose, is relational and collaborative and involves various levels of transformation from inclusion to integration and to infusion of Indigenous perspectives and approaches in CYC practice. We recognize that each institution approaches Indigenization differently due to the diversity and complexity of local Indigenous community relationships.

The Indigenized Integral Professional Competency Framework was developed using the Indigenized integral model (intention, community, behaviour and systems fit) to provide staff with tools to assess their levels of competency working with Indigenous communities. This model provides an opportunity to measure a level of baseline professional competency and skills as well as to self-reflect on your current knowledge and create a learning plan to deepen your understanding and change practice to be more holistic and balanced.

The Indigenized Integral Professional Competency Framework measures three areas of professional competencies for working with Indigenous Peoples and community partners:

- General skills and knowledge encompass a foundational knowledge and understanding of Indigenous Peoples and territory on which your institution resides. This foundational competency will also include knowledge of Indigenous history, the impacts of colonization, the Indigenous connection to land, and responsible relationships along with an understanding of the rich diversity of Indigenous Peoples, ways of knowing and being, and languages across Canada. General skills will include the ability to identify community resources for Indigenous youth as well to build the relationship of the institute with local Indigenous communities.

- Interactive competencies measures your capacity to assess your ability to provide services to Indigenous youth and to understand the systemic barriers faced by Indigenous people. Individuals will be able to identify ways to mitigate systemic challenges within the scope of their role and authority, engage in trauma-informed practices, and build relationships with Indigenous colleagues, Elders, clients, and Indigenous community members.

- Self-mastery is your deep level of self-awareness and practice. Individuals will be proficient in providing guidance to other units in ways of respecting Indigenous protocols and ways of being within the academy. Additionally, you will demonstrate ongoing commitment and responsibility to decolonize and Indigenize policies and practices.

Each quadrant of the Indigenized Integral Model framework is aligned with animal traits from coastal Indigenous knowledge. Tap on the question mark icon for each of the animals below to learn more:

Active Learning

Complete the Indigenized Integral Professional Competency Self-Assessment activity (this link opens on a new page).

Once you have completed the assessment, review your answers for the competencies you rated:

- “0” or “1” means you should flag those areas for development and training.

- “2” indicates that you are meeting the competency.

- “3” means you have exceeded the competency and are able to support and develop others in this area.

Select two areas that you feel you would like to improve in and write down some ideas of how you might be able to do so. Bring your reflections/responses to class for discussion.

Attributions

This chapter contains material adapted from Pulling Together: A Guide for Front-Line Staff, Student Services, and Advisors by Ian Cull; Robert L. A. Hancock; Stephanie McKeown; Michelle Pidgeon; and Adrienne Vedan and is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted.

This chapter contains content adapted from Historical and Contemporary Realities: Movement Towards Reconciliation by Susan Manitowabi is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted.

This chapter contains content adapted from Pulling Together: Foundations Guide by Kory Wilson is used under a CC BY-NC 4.0 licence.

Media Attributions

- Medicine Wheel © Melanie Jones is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license