2.2 Foundational Knowledge

The Child and Youth Care Certification Board (CYCCB, 2010) identifies that professional CYC practitioners should actively promote respect for cultural and human diversity as a core competency. They emphasize that the professional practitioner should seek self-understanding and be able to access and evaluate information related to cultural and human diversity; this knowledge should then be integrated into developing respectful and effective child and youth care practice (CYCCB, 2010).

Cultural and human diversity are integral to all our relationships with children, youth, and families. As a CYC student, you will have many more opportunities throughout your program to explore and learn about cultural and human diversity; the purpose of this module is to introduce you to this topic and help you begin to explore where you are in this regard and how it might influence you while on your placements.

“Education is the key to learning things we are unfamiliar with. To be an effective support to children/youth and families, it is important to understand our differences and similarities. Do not ignore or be afraid of those differences. When you encounter people from another culture, striving for cross-cultural understanding will strengthen your ability to provide support.” Shelly Nelson-Bond, Sault College CYC Program Faculty

Defining Diversity

When we begin thinking about what human diversity means, it helps to start with the basics. According to Fraser and Ventrella (2019), there are nine major factors that set groups apart from one another and give individuals and groups elements of identity, including:

- age,

- class,

- race,

- ethnicity,

- levels of ability,

- language,

- spiritual belief systems,

- educational achievement, and

- gender differences.

We could consider expanding this list to include identity markers like sexual orientation and disability.

Diversity refers to blending groups of different identities to give rise to different perspectives born out of various experiences. When diversity is valued, individual differences are respected and celebrated. Individuals should never feel they need to hide or erase parts of their identity. We’ll talk more about diversity below.

Defining Culture

Culture consists of the shared beliefs, values, and assumptions of a group of people who learn from one another and teach to others that their behaviours, attitudes, and perspectives are the correct ways to think, act, and feel. It is helpful to think about culture in the following five ways:

- Culture is learned.

- Culture is shared.

- Culture is dynamic.

- Culture is systemic.

- Culture is symbolic.

The iceberg (shown in the figure below) is a commonly used metaphor to describe culture because it illustrates the tangible and the intangible aspects of culture. When talking about culture, most people focus on the visible “tip of the iceberg,” which makes up just 10 percent of the object. The rest of the iceberg, 90 percent of it, is below the waterline and not readily visible to us.

Many people, when they find themselves in intercultural situations, pick up on the cultural differences they can see—things on the “tip of the iceberg.” Things like food, clothing, and language difference are easily and immediately obvious, but focusing only on these can mean missing or overlooking deeper cultural aspects such as thought patterns, values, and beliefs. It is imperative that CYC practitioners recognize how culture is much deeper than things that can been seen, and are open to learning about the elements below the surface as well.

More than just the clothes we wear, the movies we watch, or the video games we play, all representations of our environment are part of our culture. Culture also involves the psychological aspects and behaviours that are expected of members of a specific group. From the choice of words (message), to how we communicate (e.g., in person or by e-mail), to how we acknowledge understanding with a nod or a glance (non-verbal feedback), to internal and external interference, all aspects of communication are influenced by culture.

Defining Key Terms

The Canadian Centre for Diversity and Inclusion (2022) defines cultural competence as an “awareness and understanding of different cultures and practices, and the ability to accept and bridge differences between cultures for effective communication” (p. 8). The key here is that you are open to learning about other cultures and practices and that you respect how everyone views the world through a lens influenced by the different aspects of their identity. Sandy Macdonald, former Sault College Child and Youth Care program coordinator and faculty member, shares the following regarding cultural competence:

Cultural competence is more than simply being sensitive to cultural differences. It is a professional skill that allows you to work effectively with individuals and families whose cultural values, beliefs, traditions, and worldview may be different from your own. In practice, it means implementing strategies that are respectful of other cultures’ customs, values, and styles of communication. It also means identifying and eliminating barriers, building trust, and honouring the unique perspectives of diverse client populations.

On placement, you can practice cultural competence by showing genuine interest in clients’ cultural backgrounds and traditions, and by demonstrating humility, openness, and a sincere desire to learn. Things as simple as pronouncing clients’ names correctly, and using culturally relevant materials wherever possible, are meaningful gestures of competence and caring. (S. Macdonald, personal communication, November 22, 2021)

In “Video 1: What is Cultural Competence?” by Arkansas Open Educational Resources (OER), University students talk about what cultural competence means to them.

To access a transcript for this video, please click Watch on YouTube.

Cultural humility has been offered as an alternative to the expression cultural competence, which was used to acknowledge the importance of culture and adapting services to meet culturally-unique needs. Because cultural competence was often seen as limited and even problematic, cultural humility is increasingly being adopted within field settings, both in health and social services. Cultural humility can be described as the cultivation of self-awareness, while acknowledging the “cultural values and structural forces” that affect service user experience and opportunities (Fisher-Bone et al., 2014, p. 172). For Fisher-Bone et al. (2014), taking into account structural disparities and the intricacy of culture “strengthens our social justice commitment as social work practitioners” (p. 172).

Power is unequally distributed globally and in society; some individuals or groups wield greater power than others, thereby allowing them greater access and control over resources. Wealth, racism, citizenship, patriarchy, heteronormativity, and education are a few key social mechanisms through which power operates. Although power is often conceptualized as power over other individuals or groups, other variations are power with (used in the context of building collective strength) and power within (which references an individual’s internal strength). Learning to “see” and understand relations of power is vital to organizing progressive social change.

Privilege can be defined as a group of unearned cultural, legal, social, and institutional rights extended to a group based on their social group membership. Individuals with privilege are considered to be the normative group, leaving those without access to this privilege to be seen as invisible, unnatural, deviant, or just plain wrong. Most of the time, these privileges are automatic, and most individuals in the privileged group are unaware of them. Some people who can “pass” as members of the privileged group might have access to some levels of privilege.

Watch “Privilege is power. How you can use it to do some good!” by CBC. While you watch, reflect on the ways you have privilege. How can you use this privilege to help others?

To access a transcript for this video, please click Watch on YouTube.

Social identities are group identities. Beyond personal identities, we understand ourselves, and others recognize us, as belonging to social groups. Membership in social identity groups (e.g., religion, ethnicity, gender) are shaped in shared histories and experiences. They are further influenced by external forces such as legal decisions and historical factors and day-to-day interactions. Social identities are an important intersectional component of personal identities.

Personal identities are individual traits that make up who you are, including your hobbies, interests, experiences, and personal choices. Many personal identities are things that you get to choose and that you can shape for yourself.

In broad terms, diversity is any dimension that can be used to differentiate groups and people from one another. It involves respect for and appreciation of differences in ethnicity, gender, age, national origin, ability, sexual orientation, faith, socio-economic status, and class. But it’s more than this. It includes differences in life experiences, learning and working styles, and personality types that can be engaged to achieve excellence in teaching, learning, research, scholarship, and administrative and support services.

Inclusion is the active, intentional, and ongoing engagement with diversity, where each person is valued and provided with the opportunity to participate fully in creating a successful and thriving community. It also means creating value from the distinctive skills, experiences, and perspectives of all members of our community, allowing us to leverage talent and foster both individual and organizational excellence.

Bias is a prejudice. It is an inclination or preference towards someone/something, especially one that interferes with impartial judgement.

Oppression is the systemic and pervasive nature of social inequality woven throughout social institutions as well as embedded within individual consciousness. Oppression fuses institutional and systemic discrimination, personal bias, bigotry, and social prejudice in a complex web of relationships and structures that saturate most aspects of life in our society.

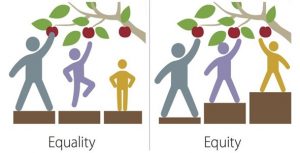

Equity is the guarantee of fair treatment, access, opportunity, and advancement for all. It requires the identification and elimination of barriers that prevent the full participation of some groups. This principle acknowledges that there are historically under-served and underrepresented populations in the social areas of employment, the provision of goods and services, as well as living accommodations. Redressing unbalanced conditions is needed to achieve equality of opportunity for all groups. Equity is not the same as equality.

Equality means each individual or group of people is given the same resources or opportunities, while equity recognizes that each person has different circumstances and allocates the exact resources and opportunities needed to reach an equal outcome.

Attributions

This chapter contains material taken from “Power, Privilege & Bias – Overview” by Queens University, licensed under CC BY-NC 4.0.

This chapter contains adapted material from Introduction to Professional Communications – Simple Book Publishing (pressbooks.pub) by Melissa Ashmun, used under a Creative Commons-Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International license.

Media Attributions

- iceberg © Laura Underwood is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Equity vs Equality © MN Pollution Control Agency is licensed under a CC BY-NC (Attribution NonCommercial) license