11 Vowels Beyond English

Having learned a basic set of ipa symbols for English vowels, it’s time to dig into the remaining vowels. In part because English is so vast, and there are so many variants, you may need these symbols to accurately describe an accent of English. But also, you may have to speak words in languages other than English, such as the names of people, places and things, or even some dialogue that switches out of English and into the first language of the character you’re playing.

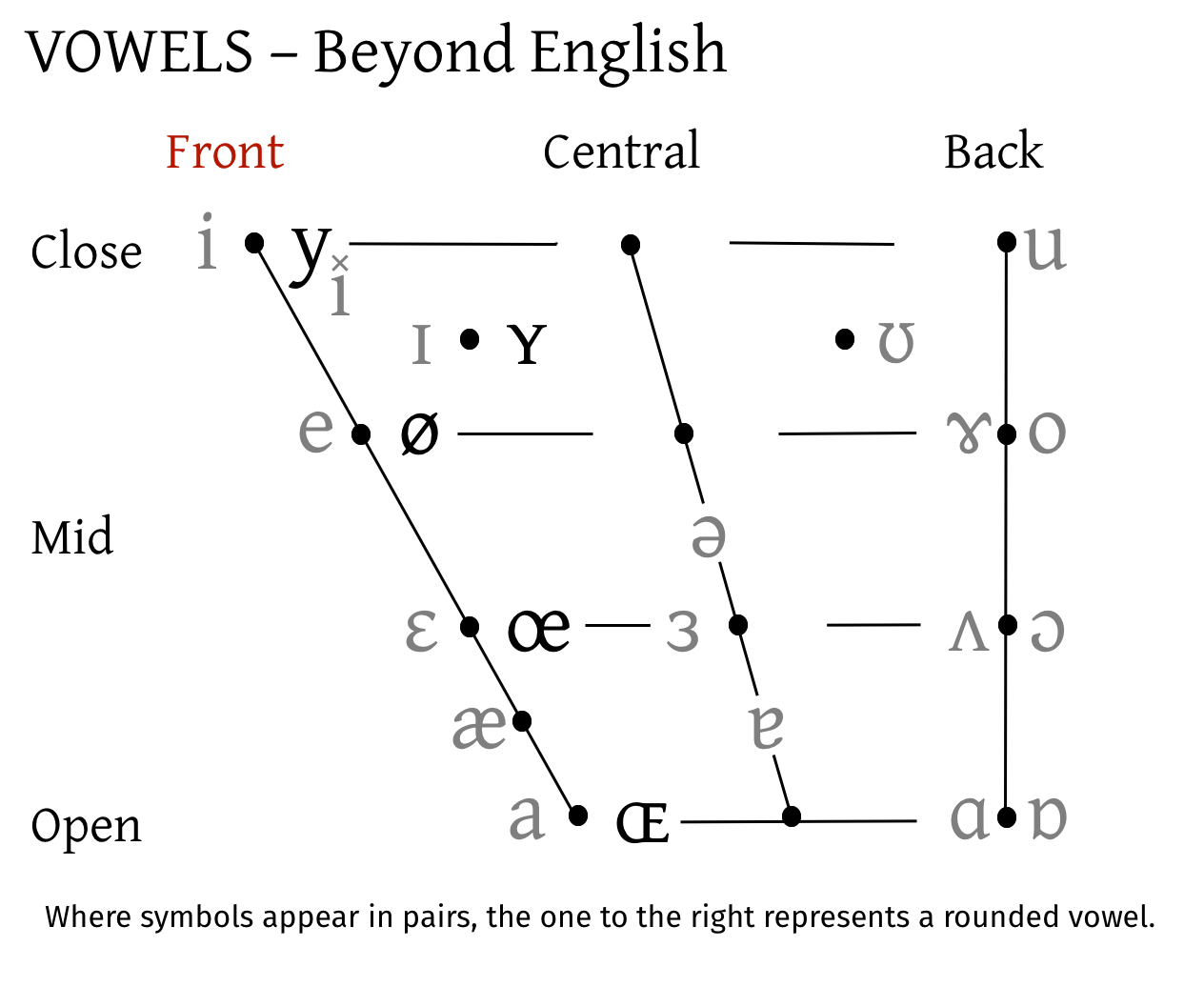

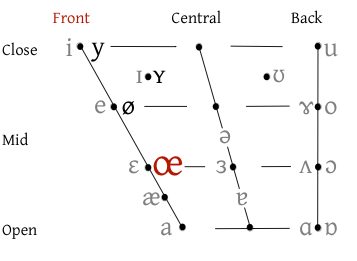

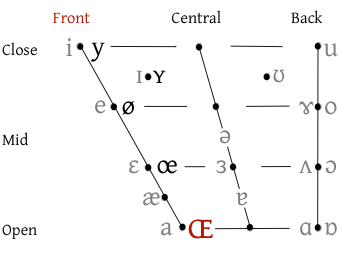

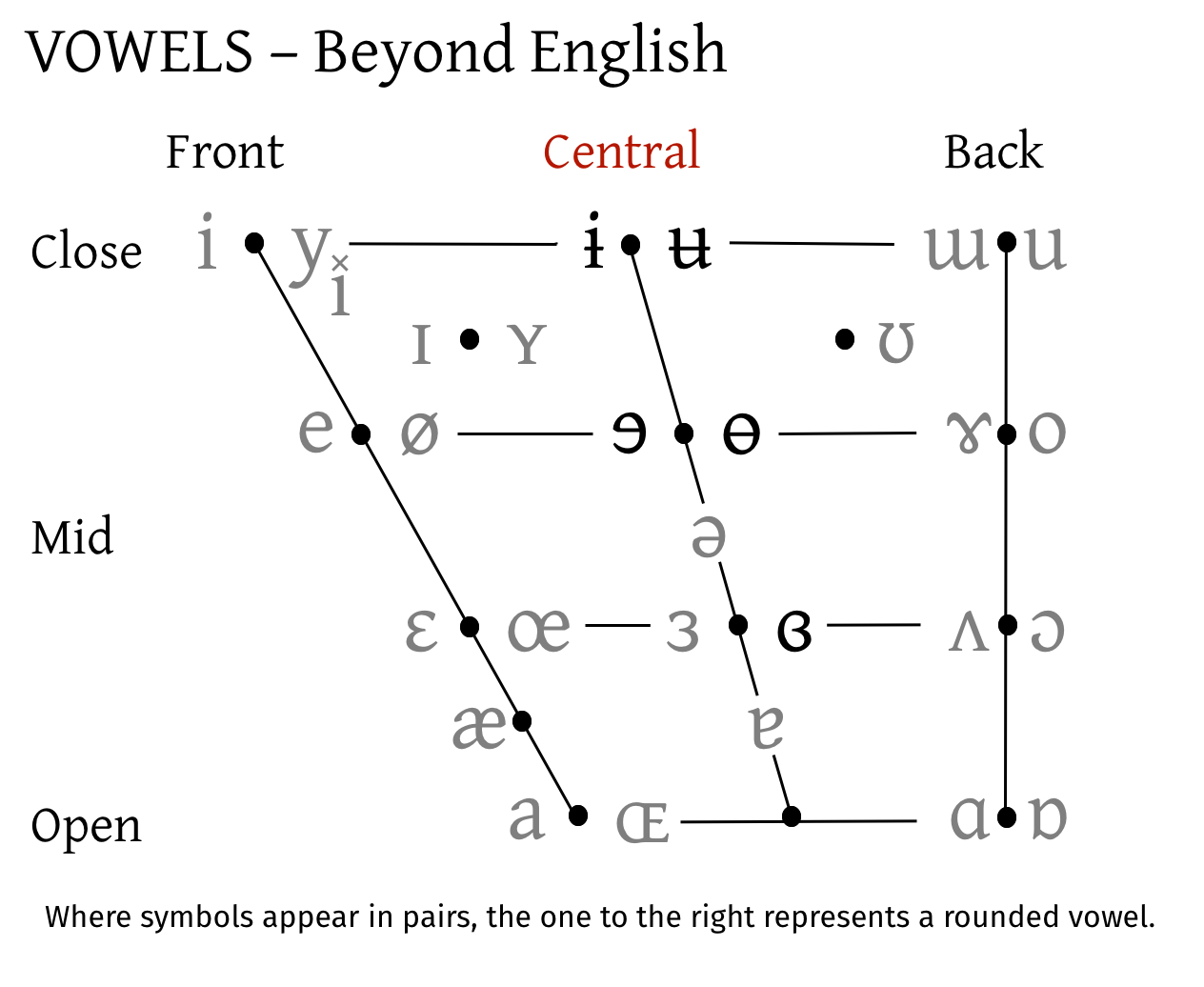

The ipa vowel chart is laid out, generally speaking, in pairs, with the symbol on the left being an unrounded version of the vowel, and the symbol on the right the rounded one. We’ve learned how [ɑ] is partnered with [ɒ], or [ʌ] pairs with [ɔ], and [ɤ] and [o] go together. We’ll use this partnering pattern to learn the remaining vowel sounds and their symbols, working from front to back and then finishing with the mid vowels, starting each section with the mouth more open, and working our way down the chart as we open the mouth more and more.

Learning to shape a new vowel articulation can be challenging, especially if the target sound reminds us of an existing vowel sound. I urge you to focus on the sensation of the movement of your articulators in isolation, separating the action of your lips from the action of your tongue. Because all English front vowels are unrounded and most English back vowels are rounded, when we try to do a front rounded vowel, it’s not surprising that our tongue and ear conspire to jump to the corresponding back rounded one! Take your time, be patient, and work to make the sound of the vowel match the sound of the provided recordings.

Front Vowels

Not including the reduced vowel [i̽], the six front vowels we’ve learned thus far are:

[i] fleece

[ɪ] kit

[e] face*

[ɛ] dress

[æ] trap

[a] bath

*Note that [e] is used for face though frequently as part of the diphthong [eɪ].

All of those have an associated rounded vowel, except for [æ]. They are:

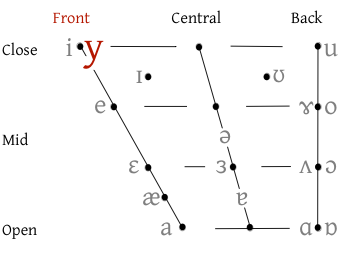

[i] → [y]

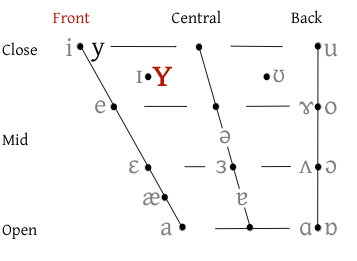

[ɪ] → [ʏ]

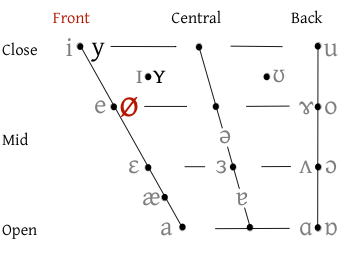

[e] → [ø]

[ɛ] → [œ]

[a] → [ɶ]

Note that, in accented versions of English, these front round vowels are not typically associated with the lexical sets that the front unrounded vowels are. So while [i] associated with fleece, [y] is typically associated with goose, which more often than not is tied to [u], the close back rounded vowel.

Lowercase Y: [y]

This can be heard here:

| y Lowercase Y close front rounded vowel  |

The vowel Lowercase Y [y] is often used as a substitute or allophone for the close back rounded vowel, [u] frequently in the goose lexical set. Its symbol is the “lowercase Y”. Some European languages, such as Albanian, Finnish, and Norwegian use the spelling <y> to represent the sound [y]. Others use variants on <u>, such as <ü> or <uu> to represent it.

Draw a short diagonal line, the left half of a <v>, and then draw the right half of a <v>, but keep going when you reach the baseline and add a little curl to the descender if you like. |

| Lexical Set Keyword: goose, though many speakers hwo have [y] in their first language, also have [u], so often it’s a situation where the English word reminds the speaker of a word from their source language that uses [y], a pronunciation “false friend.” Some English speakers use it in place of [ju], where the fronting of the [j] moves the /u/ vowel to [y], so we end up with [jy], as in a word like few, cue, beauty.

[y] is also an option for foot. The Sound & The Action: Lowercase Y [y] is the close front rounded vowel, which means the tongue is making the shape of [i], while the lips are making the shape of [u]. It helps to exaggerate the lip rounding to lock that in. I find that it helps to feel the arched, “mountain” shape of the tongue first with the jaw dropped as you say [i], so you can really feel how the tongue narrows the space between it and the alveolar ridge. Keeping the jaw as dropped as possible, and focussing on not moving the tongue, round the lips forward into a kiss-like shape, [y]. Then work to alternate between the two sounds: [i y i y i y]. Can you speed it up. Now, check your work and go back and forth between [i] and [u]—it should sound radically different! Then try going back and forth between [y] and [u]—your lips should stay locked in the lip rounded position, while the “mountain” shape of your tongue moves from the front to the back. |

|

| Linguistic Term: Close front rounded vowel.

Examples (from Wikipedia): Afrikaans Standard u [y] “you” (formal) Danish synlig [ˈsyːnli] “visible” Multicultural London English few [fjyː] “few” French tu [t̪y] “you” German über [‘yːbɐ] Korean 뒤 / dwi [ty(ː)] “back” Norwegian syd [syːd] “south” |

Small Cap Y: [ʏ]

This can be heard here:

| ʏ Small Cap Y near-close near-front rounded vowel  |

The vowel Small Cap Y [ʏ] is sometimes used in English as a substitute or allophone for the near-close near-back rounded vowel [ʊ], frequently in the foot lexical set. Its symbol is the “Small Cap Y.”

The symbol is essentially a tiny uppercase Y, drawn to be the height of most lowercase letters at the “x-height.” Starting at the x-height line, draw a short diagonal line, the left half of a <v> as if it was suspended halfway down to the baseline, and then draw the right half of the tiny <v> so that the meeting place of the two diagonal lines is halfway above the baseline. Now, keep going downward vertically to the baseline. |

| Lexical Set Keyword: foot. Accents of English that use this version include Cornwall, Multicultural London English, Estuary, Scottish, and some Southern US accents. It can also be used with the nurse lexical set (e.g. in New Zealand), or in goose Ⓑ after /j/ as in music with “liquid U” [jʏ].

The Sound & The Action: Small Cap Y [ʏ] is the near close near-front rounded vowel, which means the tongue is making the shape of [ɪ], while the lips are making the shape of [ʊ]. Wikipedia points out that most languages other than Swedish that have [ʏ] use it for a rounded vowel that has “compressed” lips, rather than protruded rounding with lip corner advancement. (As there is no official diacritic for lip compression, some authors use a diacritic of a superscript version of the <β> symbol, as the voiced bilabial fricative causes lip compression. For [ʏ], they would represent it with [ɪβ], as the cognate unrounded symbol for this vowel quality is the small cap I.) To learn the sound [ʏ], it helps to exaggerate the lip rounding to lock that that shape. Start by creating the “mountain” shape of the tongue first with the jaw dropped as you say [ɪ], so you can feel how the tongue narrows the space between it and the alveolar ridge. Keeping the jaw as dropped as possible, and focussing on not moving the tongue, round the lips forward into a kiss-like shape, [ʏ]. Then work to alternate between the two sounds: [ɪ ʏ ɪ ʏ ɪ ʏ]. Now try speeding that up. Now, check your work and go back and forth between [ɪ] and [ʊ]—it should sound radically different! Then try going back and forth between [ʏ] and [ʊ]—your lips should stay locked in the lip rounded position, while the “mountain” shape of your tongue moves from the front to the back. Finally, contrast small cap Y with lowercase Y, [y ʏ y ʏ y ʏ]—it may help to think that you’re going back and forth between [i] and [ɪ] with your lips locked in a kiss position. Having tried it with lips rounded/protruding forward in a kiss-like shape, now try it with lips compressed (the “cat’s butt” lip shape, an exo-labial articulation). Can you differentiate the two? |

|

| Linguistic Term: Near-close near-front rounded vowel.

Examples (from Wikipedia): Estuary English foot [fʏʔt] “foot” New Zealand English nurse [nʏːs] “nurse” Ulster English mule [mjʏl] “mule” Albanian yll [ʏɫ] “star” Standard Dutch nu [nʏ] “now” Quebec French lune [lʏn] “moon” German schützen [ˈʃʏ̞t͡sn̩] “protect” Swedish ut [ʏːt̪] “out” |

Slashed O: [ø]

This can be heard here:

| ø Slashed O close-mid front rounded vowel  |

The vowel [ø], aka “Slashed O,” is sometimes used as a substitute or allophone for the open-mid central unrounded vowel [ɜ] in the nurse lexical set in some non-rhotic accents. The symbol is derived from many Scandinavian languages that use <ø> to represent this sound. Many German-derived languages use o with an umlaut <ö>, while those familiar with French will recognize the [ø] sound as being connected with <eu> and <œu>.

The symbol is a lowercase o with a slash or “backslash” through it. Draw a the <o>, and then starting at 1 o’clock, slash down and back towards 7 o’clock. |

| Lexical Set Keyword: nurse, as heard in broad New Zealand English, some Welsh accent, Geordie, and South African accent.

The Sound & The Action: Slashed O [ø] is the close-mid front rounded vowel, which means the tongue is making the shape of [e], while the lips are making the shape of [o]. It helps to focus on the lip rounding so you get that well established, and then turn your attention to the position of the tongue. As the tongue is only slightly above the “equator” in the mid-point of the mouth, it can help to drop the jaw in order to feel the right space between the top of the tongue and the gum ridge as you say [e] but with your lips rounded to make the slashed-o sound [ø]. Now, alternate between the rounded and unrounded sounds: [e ø e ø e ø]. Gradually turn up the speed. Now, check your work and go back and forth between [e] and [o]—it should sound radically different! Then try going sliding through the front rounded vowels we’ve learned thus far: [y, ʏ, ø]—your lips should stay locked in the lip rounded position, while the “mountain” shape of your tongue moves lower (flattens out) to open up the vowel space. Then go back and forth, sliding through [y, ʏ, ø; ø, ʏ, y]. It can help to think [i, ɪ, e] while doing this with rounded lips, in order focus on the action of the tongue. |

|

| Linguistic Term: Close-mid front rounded vowel.

Examples (from Wikipedia): Broad New Zealand English bird [bøːd] “bird” Chechen оьпа / öpa [øpə] “hamster” Standard Danish købe [ˈkʰøːpə] “buy” Dutch neus [nøːs] “nose” Estonian töö [tøː] “work” French peu [pø] “few” German schön [ʃøːn] “beautiful” |

Ethel or Lowercase O-E Digraph: [œ]

This can be heard here:

| œ Ethel or Lowercase O-E Digraph open-mid front rounded vowel  |

The vowel [œ], represented by the lowercase O-E digraph, or “ethel” [ɛθɫ̩], is the open-mid front rounded vowel. It can be used as a substitute or allophone for the open-mid central unrounded vowel [ɜ], frequently in the nurse lexical set in New Zealand, Scouse (Liverpool), and parts of Wales. It can be argued that the [œ] is the closest rounded vowel to schwa, and indeed some people mistake [œ] for [ɚ ~ ɝ], such as the pronunciation of the German name Goethe as [ˈɡɝtə], rather than [ˈɡœtɐ]. It’s also used an option for the goat lexical set in accents such as South African.

The symbol is essentially a lowercase <o> followed by a lowercase <e>, drawn such that they join together. You can make the symbol in a single, flowing motion if you start the <o> portion at 3 o’clock, then circle around counterclockwise to 3 o’clock. Then from there, complete the lowercase <e> by going straight across, and then circle around counterclockwise again the complete it. |

| Lexical Set Keyword: nurse, or goat. (In Scouse, nurse can be merged with square.)

The Sound & The Action: Ethel [œ] is the open-mid front rounded vowel, which means the tongue is making the shape of [ɛ], while the lips are making the shape of [ɔ]. When you do it, it can help to slightly over-do the lip rounding to feel confident about that shape. Drop your jaw and shape the [ɛ] vowel, and then while not moving the tongue, round the lips to project forward to form the sound, [œ]. Then work to alternate between the two sounds: [ɛ œ ɛ œ ɛ œ]. Now, take it a little faster. You could check your work and go back and forth between [ɛ] and [ɔ], though I find [œ] and [ɔ] to be radically different from one another.! You might try going back and forth between [ø] and [ɔ]—your lips should stay locked in the lip rounded position, while the “mountain” shape of your tongue moves from the front to the back. Finally, review all the rounded front vowels we’ve learned thus far by slide downward through each one starting at [y]: [ y → ʏ → ø → œ], and then back up to the close position, [œ → ø → ʏ → y]. |

|

| Linguistic Term: Open-mid front rounded vowel.

Examples (from Wikipedia): General New Zealand English bird [bœːd] “bird” Cantonese Chinese 長 / cheung4 [tsʰœːŋ˩] “long” Dutch Standard manoeuvre [maˈnœːvrə] “manoeuvre” (loanword) General South African go [ɡœː] “go” French jeune [ʒœn] “young” Standard German Hölle [ˈhœlə] “hell” |

Small Cap Ethel or O-E Digraph: [ɶ]

This can be heard here:

| ɶ Small Cap Ethel or O-E Digraph open front rounded vowel  |

The vowel [ɶ], the Small Cap O-E digraph or “Small Cap Ethel,” represents the open front rounded vowel, which is a very rare vowel in the world’s languages. When it was introduced, some argued that there were so few languages that use it that the symbol was not necessary. Others have argued that [ɶ] should represent a near-open front rounded vowel, the rounded equivalent of [æ], and have used the symbol with an upward “tack” diacritic [ɶ̝] to raise it into that position.

The symbol is a small cap version of the capital ethel, Œ, drawn to be the height of most lowercase letters at the “x-height.” Starting at the x-height line, draw an oval shaped <o> counterclockwise, and then add three horizontal bars to it as if you were finishing off a small cap <e>. |

| Lexical Set Keyword: This sound is not used in English and is extremely rare in other languages as well.

The Sound & The Action: Small Cap Ethel [ɶ] is the open front rounded vowel, which means the tongue is making the shape of [a], while the lips are making the shape of [ɒ]. If you feel confident with your articulation of [œ], that might be a helpful starting place: make the [œ] sound and then drop your jaw even further to open up the vowel a bit more. It helps to exaggerate the lip rounding, at least at first. If you make an [a] with the jaw quite dropped, you can then round your lips forward into [ɶ]. Then work to alternate between the two sounds [a ɶ a ɶ a ɶ a ɶ]. Can you speed it up? Finally, let’s review all the front rounded vowels: [ y → ʏ → ø → œ → ɶ], and then back up to the close position, [ɶ → œ → ø → ʏ → y]. |

|

| Linguistic Term: Open front rounded vowel.

Examples (from Wikipedia): Danish grøn [ˈkʁɶ̝n] “green” Weert dialect of Limburgish bui [bɶj] “shower” Stockholm Swedish öra [ˈɶːra̠] “ear” |

Back Vowels

We’ve already learned most of the unrounded back vowels in earlier chapters: we’ve got [ɑ] paired with its rounded equivalent [ɒ], [ʌ] with the rounded [ɔ], unrounded [ɤ] with very rounded [o]. The near-close near-back rounded vowel [ʊ] doesn’t have an unrounded symbol, so if you wanted one, you’d have to use that symbol with an unrounded diacritic: [ʊ̜] and to go further, you could use the “spread” diacritic [ʊ͍]. We really only have one left to tackle, the unrounded version of the close back rounded vowel [u], which is the “doubled-u” or “turned m”, [ɯ].

![The Vowel Quadrilateral showing the new Back Rounded Vowel [ɯ].](https://ecampusontario.pressbooks.pub/app/uploads/sites/3249/2024/07/vowel-chart-English-Vowels-Beyond-English-Back.png)

Turned Lowercase M or Doubled U: [ɯ]

This can be heard here:

| ɯ Turned Lowercase M or Doubled U |

The vowel [ɯ], the turned lowercase M or “doubled U,” which represents the close back unrounded vowel, is frequently heard as an unrounded or spread variant of the goose or foot vowels. In South African English, [ɯ] is used for kit before dark L [ɫ], so kill is [kɯɫ]. Some phoneticians use this symbol to represent the final, velarized dark L [ɫ] where the tip of the tongue is uninvolved.

The symbol is an upside-down <m>, but if you think of it as a doubled <u>, that makes it easier to write. Start to write a lowercase U but just before you do the final downstroke, draw a second scooping shape, and then add your final downstroke. |

| Lexical Set Keyword: goose, foot, kit

The Sound & The Action: [ɯ] is the close back unrounded vowel, which means the tongue is making the shape of [u], while the lips are making the spread or at least the relaxed shape of [i]. Frequently, North American speakers make their goose vowel quite far forward as [u̟] or even [ʉ]. I find that it helps to feel the arched, “mountain” shape of the back of tongue reaching up towards the uvula to solidify the very back possibility of [u̠] first before attempting [ɯ]. With a locked in “dark” sounding [u], then relax the lips, and even spread the lip corners wide towards the ears to make the unrounded [ɯ]. Then work to alternate between the two sounds: [u ɯ u ɯ u ɯ] by alternatively spreading and rounding your lips, being sure not to move your tongue. Try doing it faster now. Next, check your work and go back and forth between [i] and [u]—it should sound radically different! Then try going back and forth between [ɯ] and [i]—your lips should stay locked in the lip spread position, while the “mountain” shape of your tongue moves back and forth from the back to the front. |

|

| Linguistic Term: Close front rounded vowel.

Examples (from Wikipedia): African-American English hook [hɯ̞k] “hook” (foot) Some California English goose [ɡɯˑs] “goose” (goose) New Zealand English treacle [ˈtɹ̝̊iːkɯ] “treacle” (/ɫ/) Some Philadelphia English plus [pɫ̥ɯs] “plus” (strut) South African English pill [pʰɯ̞ɫ] “pill (kit) Azerbaijani bahalı [bɑhɑˈɫɯ] “expensive” Mandarin Chinese 刺 / cì [t͡sʰɯ˥˩] “thorn” Estonian kõrv [kɯrv] “ear” Japanese 空気/kūki “air” European Portuguese pegar [pɯˈɣäɾ] “to grab” |

Central Vowels

Generally, Central vowels are more challenging to teach and learn than other vowels that live on the periphery of the vowel space. So far, we’ve learned [ə] and [ɜ], and their rhotic partners [ɚ] and [ɝ], as well as [ɐ]. The centre of the mouth is a vaguer area in the sonic landscape of vowels with fewer examples of the vowels in use, and the difference between them are subtle and harder to distinguish. We’ve got two unrounded mid vowels to learn, [ɘ] and [ɨ], before we tackle the rounded mid vowels, [ɞ], [ɵ], and [ʉ].

Reversed Lowercase E: [ɘ]

This can be heard here:

| ɘ Reversed Lowercase E |

The vowel [ɘ] is generally used as a more close version of schwa [ə]. As sych, it is the close-mid central unrounded vowel. Some speakers have the more open schwa that they use at the end of an utterance, or in dictionary forms of a word, and then they use reversed-e [ɘ] in weaker positions, or in connected speech. In some circles of the speech and accents community, the rhotic version of this vowel [ɘ˞], it is argued, represents the more close pronunciation of the letter lexical set found in many accents, as the rhotic action closes the vocal tract and brings the articulation closer to the roof of the mouth.

The symbol is a reversed lowercase <e>, which may feel similar for some people to how they might draw the number 9, though it will be shorter as it only reaches the x-height line whereas 9 (like all numerals) is the height of a tall letter like <l>. Imagining the symbol as being drawn on a clock face, start at 3 o’clock and make a horizontal line through the centre over to 9 o’clock. Then sweep the line around in a clockwise fashion to end at around 7:30. Note that this workbook does not include separate entries for rhotic versions of vowels beyond Flying 3 and Flying Schwa, [ɝ] and [ɚ]. Though it is possible to articulate rhotic versions of other vowels, such as [ɑ˞, ɔ˞, ɛ˞, ɒ˞], they are rarely used in any system of applying the ipa to transcribing speech (I can think of only one published author, Paul Meier, who does so). If you’re creating a “flying reversed e” [ɘ˞] for a rhotic articulation, you can do it in either of two ways: make the reversed e as above, and then add on the “wing” of the rhoticity diacritic. Or, you could reverse how you draw the symbol, starting at 7:30, swoop around counterclockwise to 9 o’clock, draw your line across horizontally to 3, and then continue the line to put your “wing” on. This tends to either move the horizontal bar up a bit to connect the wing in the right place (around 2 o’clock), or to lower the wing down a little). |

| Lexical Set Keyword: Non-rhotic (e.g. Australian) or rhotic in letter or nurse (some North American accents); strut (some US Southern), foot (parts of Wales), kit (New Zealand).

The Sound & The Action: [ɘ] is the close-mid central unrounded vowel, which means the tongue is arching slightly higher than schwa [ə] while the lips are relaxed. Keeping the jaw fairly closed, compare the [ɘ] sound to other, more familiar close-mid articulations, [e] and [o]. Keeping your lips relaxed, get the “mountain” of the tongue to glide backwards from [e] through [ɘ] to [o], then reverse direction and glide back to the front. Can you smooth out that action so your tongue doesn’t jump, but moves through the spectrum of possibilities between these vowels? [e → ɘ → o → ɘ → e]. Or reverse it and start at the back: [o → ɘ → e → ɘ → o]. Can you speed it up? Now, check your work and go back and forth between [ə] and [ɘ]—it should sound different, but it will be very subtle! |

|

| Linguistic Term: Close-mid central unrounded vowel.

Examples (from Wikipedia): Australian English bird [bɘːd] “bird” Cardiff English foot [fɘt] “foot” New Zealand English bit [bɘt] “bit” Southern American English nut [nɘt] “nut” Korean 어른/ŏŏleun [ɘːɾɯ̽n] “adult” Mongolian үсэр [usɘɾɘ̆] “jump” Polish mysz [mɘ̟ʂ]ⓘ “mouse” Vietnamese vợ [vɘ˨˩ˀ] “wife” |

Barred Lowercase I: [ɨ]

This can be heard here:

| ɨ Barred Lowercase I |

The vowel [ɨ], the Barred Lowercase I, was used in previous editions of this book in place of what is now represented by the mid-centralized /i/, [i̽] which represents a vowel frequently used in the happy lexical set. In official ipa usage, [ɨ] is the close central unrounded vowel, and it is usually called “barred-i”. (Barring a symbol generally means that a symbol from the periphery of the vowel chart is moved centrally, so we see a similar pattern in barred-u [ʉ] and barred-o [ɵ]. In other cases, where we only want to represent a vowel being closer to the central zone, we use the diaersis or umlaut diacritic, e.g. [ɛ̈] or [ɔ̈]. Some authors prefer to use the + or – diacritics, e.g. [ɛ̠] or [ɔ̟].

The symbol is super easy to draw: make a lowercase I <i>, and then “bar” it as if you were finishing off a lowercase <t>. |

| Lexical Set Keyword: foot (Inland US Southern or Southeastern British English), kit (South African, US Southern), goose (some Southeastern British English).

The Sound & The Action: [ɨ] is the close central unrounded vowel, which means the tongue is as close as it is for [i], but the arch or “mountain” of the tongue is highest in the centre, near the highest point of the hard palate. To me, the shape of the tongue for semivowel [j] or “yod”, with the middle of the tongue very close to the centre of the hard palate, is the best starting place for this vowel. Shape the [j], then inhale through that tongue shape to feel where the vocal tract is narrowed. Then lower the tongue a tiny bit to find the [ɨ] vowel. Compare it with [i] by going forward from yod to [i], ad in [ji], and then going down from yod to [ɨ], [jɨ]. Now, go back and forth between the two[ji jɨ ji jɨ ji jɨ]. The central version should feel more “schwa-ish” than the front one, but still maintain the height for the front vowel. It’s as if you’re making your fleece vowel sound “murkier,” compared to the brightness of the front version. Now, try it without the yod, [i → ɨ → i → ɨ → i → ɨ]. You can check your articulation by going back and forth between [i] and [ə]—it should sound quite different! Then try moving through the unrounded central vowel from closest to most open: [ɨ → ɘ → ə → ɜ → ɐ]. I find it’s easiest to do this if you intone the vowels all on one pitch, so that the sounds do not get lower in pitch as you open your mouth: focus on the change in vowel qualities and the shape of your tongue, and don’t get distracted by the pitch. Next, can you go from mid-open to the close version [ɐ → ɜ → ə → ɘ → ɨ]? |

|

| Linguistic Term: Close central unrounded vowel.

Examples (from Wikipedia): Inland Southern US English good [ɡɨ̞d] “good” foot South African English lip [lɨ̞p] “lip” kit Southeastern English rude [ɹɨːd] “rude” goose Mandarin 十/shí [ʂɨ˧˥] “ten” Irish goirt [ɡɨ̞ɾˠtʲ] “salty” Romanian înot [ɨˈn̪o̞t̪] “I swim” Russian ты/ty [t̪ɨ] “you” (singular/informal) Sümi sü [ʃɨ̀] “to hurt” Tamil vály (வால்) [väːlɨ] “tail” Standard Turkish sığ [sɨː] “shallow” |

Closed Turned Epsilon, or “The Bum”: [ɞ]

This can be heard here:

| ɞ Closed 3 or Reversed Epsilon, or “The Bum” |

The mid-open central rounded vowel [ɞ], represented by the closed turned epsilon, closed 3, or “the bum” is often used as a substitute or allophone for the mid-open central unrounded vowel [ɜ], frequently in the nurse lexical set, though it can be used elsewhere such as in the strut or lot lexical sets.

The symbol is essentially a small cap 3, drawn to be the height of most lowercase letters at the “x-height,” that is “closed,” i.e. the left side of the <ɜ> symbol are joined, so it’s as if it were an <o> on the left, and a small <3> on the right. Start by drawing the [ɜ] symbol, and then, as you come to where that symbol would normally end, keep the line going until your line joins at that starting place. |

| Lexical Set Keyword: Most commonly used as a rounded version of [ɜ] in nurse or letter, though it can also occur in strut in Irish English, and lot in New Zealand English.

The Sound & The Action: [ɞ] is the mid-open central rounded vowel, which means the tongue is making the shape of [ɜ], while the lips are making the shape of [ɔ]. It helps to exaggerate the lip rounding to lock that in. I find that it helps to feel the flat, central shape of the tongue first with jaw dropped as you say [ɜ], so you can really feel the space above the tongue. Keeping the jaw as dropped as possible, and focussing on not moving the tongue, round the lip corners forward into a quite open rounded shape, [ɞ]. Then work to alternate between the two sounds: [ɜ → ɞ → ɜ → ɞ → ɜ → ɞ]. Try speeding it up. Now, let’s compare the rounded version of [ɛ], which is [œ]. I find that [ɞ] and [œ] are very similar in sound, and frequently confuse the two. Try this pattern where you alternate adding or removing lip rounding and moving the tongue from front to central: [ɛ → œ → ɞ → ɜ | ɜ → ɞ → œ → ɛ]. Now try just going back and forth between the front and central versions of the mid-open rounded vowels [œ → ɞ → œ → ɞ → œ → ɞ]. Finally, try sliding through the mid-open rounded vowels, from [œ] to [ɞ] to [ɔ] and back, [ɔ] to [ɞ] to [œ]. You should feel your lips locked into that lip-corner advancement shape, and your tongue moving through front, central, and back, all at the mid-open height. |

|

| Linguistic Term: Mid-open central rounded vowel.

Examples (from Wikipedia): Irish English but [bɞθ̠] “but” strut New Zealand English not [nɞʔt] “not” lot Afrikaans lug [lɞχ] “air” Parisian French port [pɞːꭓ] “port”, “harbour” Irish tomhail [tɞːlʲ] “consume” Navajo tsosts’id [tsʰɞstsˈɪt] “seven” Panará [kɾəˈkɞ] “trousers” |

Barred Lowercase O: [ɵ]

This can be heard here:

| ɵ Barred Lowercase O |

The mid-close central rounded vowel [ɵ], the barred lowercase O, or simply Barred-O, is often used as a substitute or allophone for the near-close near-back rounded vowel [ʊ], usually in the foot lexical set, though it can be used elsewhere such as in the goat and nurse lexical set. (Barring a symbol generally means that a symbol from the periphery of the vowel chart is moved centrally, so we see similar symbols in barred-u [ʉ] and barred-i [ɨ].)

The symbol is essentially a lowercase <o>, with a horizontal line drawn across it. Note the similarity between it and the symbol for the voiceless dental fricative [θ], which is made with a skinny capital <O> and its bar is at the x-height line, while the barred-o [ɵ] is much shorter, a lowercase symbol, and its bar is much lower. |

| Lexical Set Keyword: foot but also goat or nurse.

The Sound & The Action: [ɵ] is the mid-close central rounded vowel, which means the tongue is making the shape of [ɘ], while the lips are making the shape of [o]. As with any lip-rounded vowel, it always helps to exaggerate the lip rounding to lock tat in. I find that it helps to form the rounded back shape of [o] first, which helps to establish the tongue height and the lip rounding, and then move the “mountain” of the tongue to the central region for [ɵ]. Then, with the the tongue locked into what feels like the mid-close central shape, unround your lips to check it against [ɘ]. There is some value in going back and forth between [o] and its barred counterpart [ɵ] to try to get a better sense of that tongue action, and to tune your ear to what [ɵ] sounds like: [o → ɵ → o → ɵ → o → ɵ]. Can you speed it up? Try comparing all the mid-close rounded vowels [ø → ɵ → o | o → ɵ → ø]. |

|

| Linguistic Term: Close-mid central rounded vowel.

Examples (from Wikipedia): Welsh (Cardiff) English/South African English foot [fɵt] “foot” Modern Received Pronunciation English foot [fɵʔt] “foot” Hull English goat [ɡɵːt] “goat” Azeri Tabriz göz گؤز [gɵz] “eye” Cantonese Chinese 出/ceot7 [tsʰɵt˥] “to go out” Dutch Standard hut [ɦɵt] “hut” New Zealand English bird [bɵːd] “bird” French je [ʒɵ] “I” Kazakh көз [kɵz] “eye” Mongolian өгөх/ögökh [ɵɡɵx] “to give” |

Barred Lowercase U: [ʉ]

This can be heard here:

| ʉ Barred Lowercase U |

The close central rounded vowel [ʉ], represented by the barred lowercase U, or simply barred-u, is often used as a substitute or allophone for the close back rounded vowel [u], frequently in the goose lexical set, though it can be used elsewhere such as in the foot lexical set. (Barring a symbol generally means that a symbol from the periphery of the vowel chart is moved centrally, so we see similar symbols in barred-i [ɨ] and barred-o [ɵ].)

Like the other barred symbol, this symbol is easy enough to draw; draw a lowercase-u and then bar it. |

| Lexical Set Keyword: goose in place of [u] in places like Australia, New Zealand, contemporary RP in Southern England, Scotland, Liverpool, and Ulster, and even some variants of in the US; foot, in place of [ʊ], in Estuary English and some forms of Southern American; and strut on Shetland in the north of Scotland.

The Sound & The Action: [ʉ] is the close central rounded vowel, which means the tongue is making the shape of [ɨ], while the lips are making the shape of [u], halfway between [u] and [y]. This means the tongue is as close as it is for the [i] and [u]], but the arch or “mountain” of the tongue is highest in the centre, near the highest point of the hard palate. Like with barred-i [ɨ], the shape of the tongue for semivowel [j] “yod”, with the middle of the tongue very close to the centre of the hard palate, is the best starting place for this vowel. Shape the [j], then inhale through that tongue shape to feel where the vocal tract is narrowed. Then round your lips before you lower the tongue a tiny bit to find the [ʉ] vowel. Compare it with [u] by going forward from yod to a very back [u], as in [ju], and then going down from yod to [ʉ], [jʉ]. Now, go back and forth between the two, [ju jʉ ju jʉ ju jʉ]. The central version should feel “brighter” than the back one, but still maintain the height for the back vowel. It’s as if you’re making your goose vowel sound “murkier,” compared to the brightness of the central version. Now, try it without the yod, [u → ʉ → u → ʉ → u → ʉ]. Then try moving through the rounded central vowels from closest to most open: [ʉ → ɵ → ɞ]. I find it’s easiest to do this if you intone the vowels all on one pitch, so that the sounds don’t get lower in pitch as you open your mouth: focus on the change in vowel qualities and the shape of your tongue, and don’t get distracted by the pitch. Next, can you review the rounded vowels from the close front to close central to close back [y → ʉ → u → ʉ → y]? |

|

| Linguistic Term: Close front rounded vowel.

Examples (from Wikipedia): Australian, New Zealand, Contemporary RP, Scouse, South African English goose [ɡʉːs] “goose” Estuary, Rural white Southern American English foot [fʉ̞ʔt] “foot” Shetland English strut [stɹʊ̈t] “strut” Standard Northern Dutch nu [nʉ] “now” Munster Irish ciúin [cʉːnʲ] “quiet” Ulster Irish úllaí [ʉ̜ɫ̪i] “apples” Southern Kurdish müçig [mʉːˈt͡ʃɯɡ] “dust” Russian кюрий/kyuriy/kjurij [ˈkʲʉrʲɪj] “curium” Scots buit [bʉt] “boot” Scottish Gaelic co-dhiù [kʰɔˈjʉː] “anyway” Tamil வால் [väːlʉ] “tail” |

- MRI 2. Janet Beck. Front close rounded vowel (cardinal 9). Seeing Speech. Glasgow: University of Glasgow, 2018. Web. 21 August 2024. https://seeingspeech.ac.uk/ipa-charts/?chart=4&datatype=4&speaker=1#location=121 ↵

- MRI 2. Janet Beck. Front close-mid rounded vowel (cardinal 10). Seeing Speech. Glasgow: University of Glasgow, 2018. Web. 21 August 2024. https://seeingspeech.ac.uk/ipa-charts/?chart=4&datatype=4&speaker=1#location=248 ↵

- MRI 2. Janet Beck. Front open-mid rounded vowel (cardinal 11). Seeing Speech. Glasgow: University of Glasgow, 2018. Web. 21 August 2024. https://seeingspeech.ac.uk/ipa-charts/?chart=4&datatype=4&speaker=1#location=339 ↵

- MRI 2. Janet Beck. Front open rounded vowel (cardinal 12). Seeing Speech. Glasgow: University of Glasgow, 2018. Web. 21 August 2024. https://seeingspeech.ac.uk/ipa-charts/?chart=4&datatype=4&speaker=1#location=630 ↵

- MRI 2. Janet Beck. Back close unrounded vowel (cardinal 16). Seeing Speech. Glasgow: University of Glasgow, 2018. Web. 21 August 2024. https://seeingspeech.ac.uk/ipa-charts/?chart=4&datatype=4&speaker=1#location=623 ↵

- MRI 2. Janet Beck. Central close unrounded vowel (cardinal 17). Seeing Speech. Glasgow: University of Glasgow, 2018. Web. 21 August 2024. https://seeingspeech.ac.uk/ipa-charts/?chart=4&datatype=4&speaker=1#location=616 ↵

- MRI 2. Janet Beck. Central close rounded vowel (cardinal 18). Seeing Speech. Glasgow: University of Glasgow, 2018. Web. 21 August 2024. https://seeingspeech.ac.uk/ipa-charts/?chart=4&datatype=4&speaker=1#location=649 ↵