1 New Consonant Shapes

Esh: [ʃ]

These sounds can be heard here:

| Symbol | Spelled | As in… | Name | Notes |

| [ʃ] | “sh” | “ship” | Esh | This symbol drops below the baseline and rises to the topline. Think of it as a stretched “s”. It is built from the top ascender of an “f”, and the bottom, descender portion of a “j”. |

| The Sound & the Action: Esh [ʃ] is made similar to [s], but with the tongue a narrow groove a little further back behind the gum/alveolar ridge, and with a slightly larger channel for the air to pass through. The lips usually round forward slightly, as well. Sometimes the sound [ʃ] is found in a word where, historically the sound <sy> has merged or coalesced into /ʃ/, as you might find in “issue, tissue.” | ||||

| Linguistic Term: Voiceless Postalveolar Fricative. | ||||

| Spellings | crucial, champagne, fuchsia, sure, tension, fascist, Scheherazade, shame, militia, patience | |||

Ezh: [ʒ]

| Symbol | Spelled | As in… | Name | Notes | |||

| [ʒ] | “zh” | “vision” | Ezh |

This symbol drops below the baseline—the middle point of the “3” shape is on the baseline. It is similar to many script Z’s, as in “z”.

|

|||

| The Sound & the Action: Ezh [ʒ] is the voiced cognate of [ʃ]: it is made in the same manner (fricative) and place (postalveolar, with the tongue making a groove a small distance back from the gum/alveolar ridge), but with voicing. It comes to English from French predominately and occurs exclusively in “loan words” from foreign languages. Sometimes the sound [ʒ] is found in a word where, historically, the sound /zj/ has merged or coalesced into /ʒ/, as you might find in “azure, casual, visual.” | |||||||

| Linguistic Term: Voiced Postalveolar Fricative. | |||||||

| Spellings |

Gigi, bijou, beige, Asian, azure, Zsa Zsa, zhuzh

|

||||||

Drag and Drop: Practice Material for [ʃ] and [ʒ]

Theta: [θ]

These sounds can be heard here:

| Symbol | Spelled | As in… | Name | Notes | |||

| [θ] | “th” | “thin” | Theta | This symbol is tall—it rises to the topline. Draw a skinny capital “O” and strike through it. I like to imagine the “O” part is the shape of the mouth, and the crossbar is the tongue touching the teeth. | |||

| The Sound & the Action: Theta [θ] is a voiceless consonant made with the tongue touching the edge of the upper front teeth; the tongue may stick out slightly. Both “th” sounds come to English from Scandinavian languages, and are hard for many non-native English speakers to make. | |||||||

| Linguistic Term: Voiceless Dental* Fricative (*sometimes called interdental). | |||||||

| Spellings |

Bath, breath

|

||||||

Eth: [ð]

| Symbol | Spelled | As in… | Name | Notes | |||

| [ð] | “TH” | “those” | Eth[ɛð] | This symbol looks like a backward 6, with a diagonal cross bar. Draw a “d”-like shape on a slant to the left, then cross the top bar like a “t”. | |||

| The Sound & the Action: Eth [ð] is the voiced cognate of [θ], but with the vocal folds vibrating. It is made in the same place and manner, with the tongue between the upper and lower teeth, but it is voiced. | |||||||

| Linguistic Term: Voiced Dental Fricative. | |||||||

| Spellings |

Brother, breathe

|

||||||

You may notice that /ð/ appears at the start of a lot of “little words”—what we call function words—like they, them, their/there, those, the, this, then, therefore, etc., and as such, is far more common in the English language. It is not exclusive to this kind of word, also appearing in operative words, such as mother, brother, weather, bathe, etc.

Drag and Drop: Practice Material for [θ] and [ð]

Review Session 1

Eng: [ŋ]

This can be heard here:

| Symbol | Spelled | As in… | Name | Notes | |||

| [ŋ] | “ng” | “sing” | Eng | This symbol drops below the baseline. Draw an “n” and then add a hook tail, like finishing a [ɡ] or a [j]. | |||

| The Sound & the Action: Eng [ŋ] is a nasal sound, meaning the sound travels through the nose, just like the other nasals we’ve met, [m, n]. This sound is made with the back of the tongue in contact with the dropped soft palate or velum, sending the sound out the nose rather than exiting out the mouth. | |||||||

| Linguistic Term: Voiced Velar Nasal. | |||||||

| Spellings | singing, anchor, zinc, ankle, sphinx, rang, dinghy. Some “ng” spellings are pronounced [ŋɡ] as in hunger, dangle, or longer. On the other hand, note that many words with [ŋ] donʼt have “ng” in them, like bank, link, sunk, honk. In almost all cases like this, the “n” is followed by [k] sound. | ||||||

Turned W: [ʍ]

This can be heard here:

| Symbol | Spelled | As in… | Name | Notes | |||

| [ʍ] | “wh”

/hw/ |

“white” | Turned W | Make sure the points of the “w” are sharp, and don’t bother with serifs. It shouldn’t look like an [m]. | |||

| The Sound & the Action: Turned W [ʍ] is a sound that is heard rarely in speech today. It is the voiceless cognate of [w] and occurs only in words spelled with “wh.” However, not all “wh” words can be said with this sound – many “wh” words are pronounced with [h], such as who, whoever, whom, whomever, which, whole, whore. Memorable pop-culture references to it are from the film Hot Rod (2007) “My safe word will be whiskey,” and Family Guy “barely Legal” (S5E8), Stewie’s pronunciation of “Cool Whip.” | |||||||

| Linguistic Term: Voiceless Labio-Velar Fricative. | |||||||

| Spellings | where (some “wh” spellings are never pronounced as [ʍ] because they’re pronounced with [h]. Some people argue that the word “why” should always be pronounced as [waɪ]). | ||||||

Drag and Drop: Practice Material for [ŋ], [ŋɡ], [w], and [ʍ]

Barred L or Dark L: [ɫ]

This can be heard here:

| Symbol | Spelled | As in… | Name | Notes | |||

| [ɫ] | “L” | “all” | Barred L or Dark L | The bar on this L is really a curvy “tilde,” helping to differentiate it from a “t” with its straight cross bar. This sound is made only at the end of syllables. | |||

| The Sound & the Action: Barred L [ɫ], the so-called Dark L, occurs after a vowel, frequently after a back vowel, and is made with the back of the tongue archinɡ up near the soft palate. (Compare this, in a word like “ball,” with a Light L, as in the word “love”.) Some people use a voiced velar lateral approximant [ʟ], with no front edge of tongue action, especially at the end of an utterance. In some accents, the foot and/or strut lexical set before /l/ in words like bull, dull, full, gull, hull, wolf, cull, pull, feature a syllabic version of the sound, even in stressed syllables, as in wool [ˈwʟ̩].

View an MRI of [ɫ] |

|||||||

| Linguistic Term: Voiced Velarized Alveolar Lateral Approximant. | |||||||

| Spellings | all, mold (In some spellings “l” is silent, e.g. “calf, calm.”) | ||||||

Drag and Drop: Practice Material for [l] and [ɫ]

Shades of L

While there are accents which use a light final /l/ (most notably Irish English festures one), final /l/ in most Englishes is dark, that is, it’s made with both the tip of the tongue articulating behind the upper front teeth, and the back of the tongue arching up towards the soft palate or velum, in roughly the same shape as is used for the vowel /u/ as in goose. This action of raising the back of the tongue towards the velum is called “velarization.” Final /l/ can vary between quite light or dark, depending on the vowel that precedes it, and the speaker’s style of speech. Some use very dark /l/, or [ɫ], after all vowels, while others only use dark /l/ after back vowels. Most speakers never use dark /l/ in the middle of words like “alive, belittle,” where the /l/ begins a stressed syllable, though some might use a dark /l/ in words like “hollow, pillar, frolic,” where it appears between two vowels when it ends one syllable and/or starts an unstressed syllable. I feel that a skilled actor should be capable of doing either—using light or dark /l/ in any setting.

First remember what a bright /l/ sounds and feels like by saying:

“A light, luscious, lovely little liquid. La la la!”

Notice the action of the front edge of the tongue curling up toward the alveolar ridge behind the upper front teeth. Explore a dark /l/ sound with:

“Well, we will pull for Paul to get his pail.”

Feel how the back of the tongue rises toward the soft palate as you make the /l/ shape with the front of the tongue. It’s also possible that you don’t use [ɫ] on some or even all of them—does your tongue tip stay down, behind your lower front teeth while saying these /l/ sounds? If so, you’re likely making use of the voiced velar lateral approximant [ʟ].

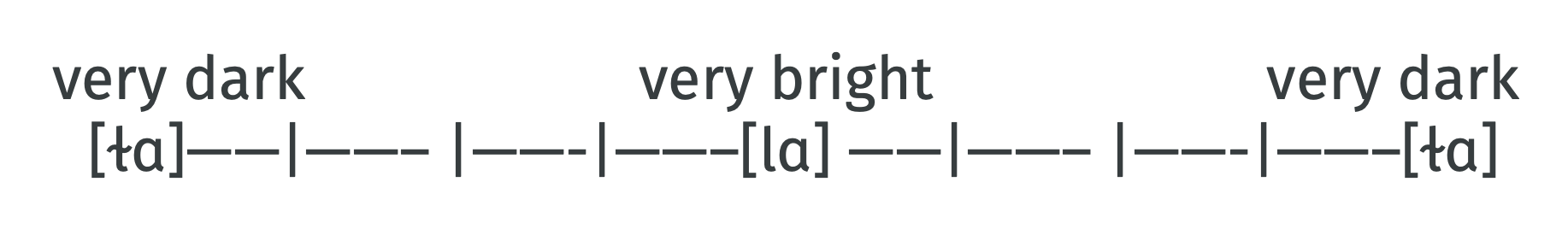

You can hear me demonstrate these sentences here:

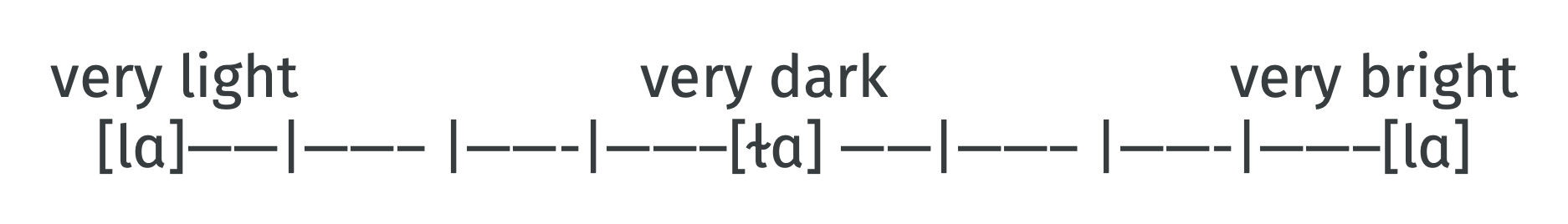

Perhaps some of you would use a less dark /l/ on well, will or pail, because the vowel before the /l/ is forward in the mouth, which might influence the following /l/. Now try saying both phrases the other way around, beginning words with [ɫ]and ending words with [l], which may sound a little Eastern European (starting with a dark /l/) or Irish (ending with a light /l/). Note that it’s unlikely that a speaker would start a word with the voiced velar lateral approximant [ʟ], but I suppose it’s not impossible!

You can hear both phrases here:

Now apply the same principle to /l/ in the middle of words:

“Paula Miller and Yolanda Follis, were finding their salad filling.”

With a light /l/, the words with media /l/ should feel as though the /l/ begins the second syllable:

“Pau-la Mi-ller and Yo-landa Fo-llis, were finding their sa-lad fi-lling.”

With a dark /l/ in the mix, you should feel the /l/ action at the end of the first syllable:

“Paul-la Mil-ler and Yol-landa Fol-lis, were finding their sal-lad fil-ling.”

(You’ll notice that I added some /l/s to the spelling in order to highlight this quality.) Can you feel how the action of the back of the tongue toward the soft palate affects the vowel before the [ɫ]? That dark /l/ quality, caused by the narrowing of the vocal tract at the soft palate/velum, also makes the preceding vowel feel “dark,” too. We anticipate the place of the [ɫ], and so we add velarization to the vowel, too.

This sentence, with both light and dark /l/ can be heard here:

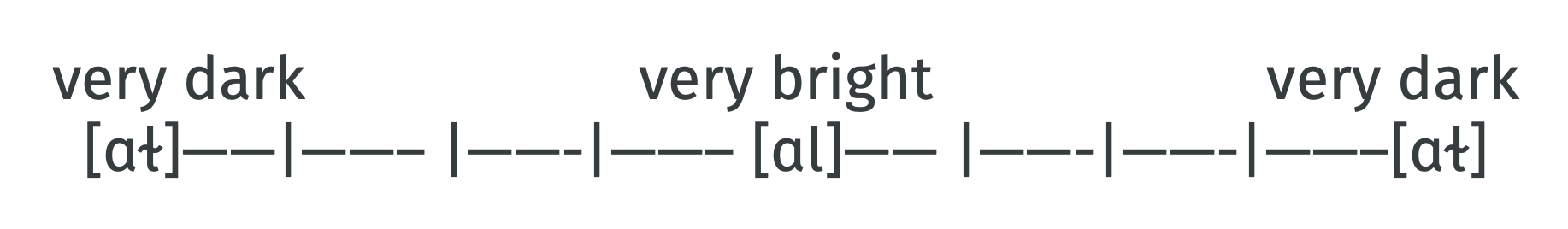

Experiment with the vowel [ɑ], as in “Father,” with a dark /l/, or [ɫ], to say “all,” and then gradually shift with each repetition of “all,” toward shades of lighter /l/ until you get to a “bright” /l/. Can you feel the back of your tongue rising up toward your soft palate on the dark /l/, and can you isolate just the front of your tongue for the brighter /l/?

Try its opposite:

You can hear a demonstration of these here:

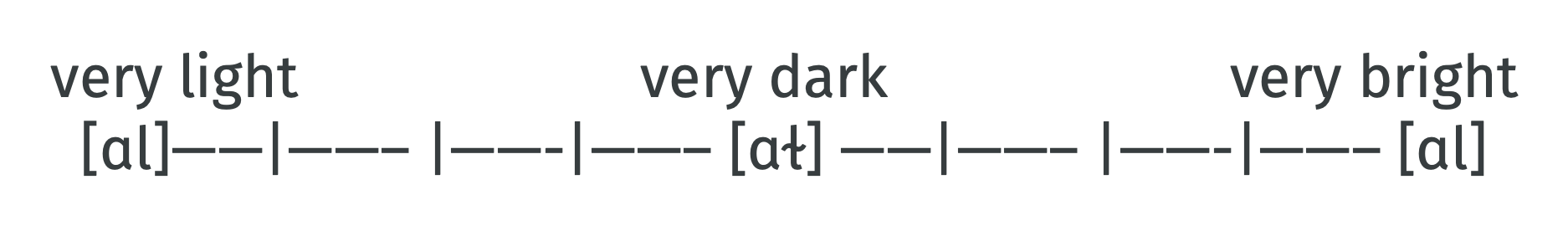

Now try starting with a light /l/, and then gradually make the initial /l/ darker, like this:

And try its opposite:

These can be heard here:

Affricates

The next pair of symbols represent affricate sounds, which are an interesting combination. English has two affricate pairs, and we hear them at the beginning and ending of the words church and judge. Affricates are consonants that begin as a stop (like [t, d]), and end with a release like a fricative (such as [ʃ, ʒ], made in the same place. Though it is tempting to think of these as two sounds, they really function as a single unit, and they burst forth in a manner similar to a stop plosive. Some people use a tie bar to link the symbols, so that they appear as a single unit, [t͡ʃ, d͡ʒ], though it isn’t required, and I prefer not to use tie bars, generally. Other languages have different affricates, such as [pf] in German words such as “pfennig,” [ts] in the Japanese word “tsunami,” or [dz] in the Greek word “tzatziki.”

T – Esh: [tʃ]

These sounds can be heard here:

| Symbol | Spelled | As in… | Name | Notes | |||

| [tʃ] | “ch” | “church” | T-Esh | This affricate pair (both sounds made together) combines two symbols. Don’t separate the two sounds! | |||

| The Sound & the Action: T-Esh [tʃ] is a voiceless affricate that begins in the [t] place and releases in the [ʃ] manner. It is an abrupt action that sounds like a single sound. It can also be said non-pulmonically as an “ejective”, often at the end of an utterance, which is transcribed with the apostrophe diacritic, which [wɪtʃʼ]. | |||||||

| Linguistic Term: Voiceless Palato-alveolar Affricate. | |||||||

| Spellings | cello, ancient, chap, righteous, question, capture, ditch | ||||||

D – Ezh: [dʒ]

| Symbol | Spelled | As in… | Name | Notes | |||

| [dʒ] | “j” or “gh” | “judge” | D-Ezh | Both sounds are made at once—note this is NOT [dz]. | |||

| The Sound & the Action: D-Ezh [dʒ] is the voiced cognate of [tʃ], meaning it is made in the same place/manner, but has voicing from the vocal folds vibrating. It is an abrupt action that sounds like a single sound, similar to stop plosive ones. | |||||||

| Linguistic Term: Voiced Palato-alveolar Affricate. | |||||||

| Spellings | educate, edge, adjective, gem, suggest, jade, change | ||||||

Drag and Drop: Practice Material for [tʃ] and [dʒ]

Review Session 2

MAYBE ADD SPEAKING?HEARING COMPARISON PARTNER EXERCISE HERE

Turned R: [ɹ]

This can be heard here:

| Symbol | Spelled | As in… | Name | Notes | |||

| [ɹ] | “r” | “run” | Turned R |

The normal, right side-up “r” symbol is used for the trilled R (as in Parisian French or Scots). Draw this symbol by making a “u”, only start at the bottom. |

|||

| The Sound & the Action: In North America, consonant R is made in a number of ways. Turned R [ɹ] is made with the tongue tip rising up slightly but without the tongue root pulling back. In 2023, this became known as a “crunchy /r/,” thanks to TikTok. The “retroflex-R” [ɻ] is made with the tongue tip curling back into a retroflex (back-bending) pattern, with the underside of the tongue tip pointing at the palate; its symbol has the right-facing hook added at the bottom of the turned-R, similar to other retroflex consonants, such as [ʈ , ɳ , ʐ , ɭ]. (See the section on the Retroflex Place for more information.) The symbol [ɹ̈], where the diaeresis—also know as umlaut, or two dots diacritic—means “centralized,” represents the so-called “molar /r/” which is made with the tongue root pulled back. Generally speaking, we’ll default to using the turned-R symbol [ɹ] in our work here. | |||||||

| Linguistic Term: Voiced Alveolar Approximant. | |||||||

| Spellings | rip, cherry, rhyme, hemorrhage, wreck | ||||||

Rhoticity or R-Colouring

It is worth noting that there are typically two kinds of accents of English, what linguists call rhotic accents and non-rhotic accents (the first syllable is like “row a boat,” after the Greek letter Rho (ρ), and the second, like “tick”). In rhotic accents, /r/ after vowels is pronounced with r-colouring, while in non-rhotic accents, the r-quality is omitted after a vowel. Interestingly enough,/r/ before a vowel maintains its r-quality in both kinds of accent. In a non-rhotic accent, a word like par is pronounced the same as Pa. Examples of rhotic accents might be so-called General American, Irish English, Scottish English, while some examples of non-rhotic accents might be Standard British, so-called Received Pronunciation, many forms of African American speech, Australian English, Cockney and other accents of London, etc. As a result of the differing behaviour of /r/ in these contexts, we classify them as two different kinds of /r/: Consonant R and Vowel R.

Consonant R vs. Vowel R

There are two kinds of /r/ in English- /r/ that functions like a consonant and initiates syllables, and /r/ that functions as part of a vowel or diphthong. Initial /r/ (at the beginnings of words, alone or in consonant clusters) is always a consonant /r/, e.g. “red, ripe, raw, wren”. It is always represented by the symbol [ɹ]. (Note that the symbol [r] is used by the IPA to represent the trilled /r/ made at the front of the mouth, with the tip or apex of the tongue on the alveolar ridge (hence its Linguistic term: Alveolar Trill). Though [r] is quite rare in most varieties of English, it is fairly common in other languages.

Meanwhile, Final /r/ is, for the most part, a vowel /r/, e.g. “bar, beer, bore, burr, bear,” that could lose its r-quality in a non-rhotic accent. It is not represented by [ɹ], and we will learn the symbols used to represent them as we work our way through the vowels later in the vowels section.

However, if Final /r/ is followed by a word that begins with a vowel, in continuous speech we generally add a consonant /r/ to the beginning of that new word. For instance, “ginger͜ ale” and “further ͜up” become more like “ginge-rale” and “furthe-rup.” This is especially evident in non-rhotic accents that use a Linking /r/ to join words in this fashion. Another option here is to use a rhotic vowel at the end of the first word, and then use a glottal stop [ʔ] to begin the word that follows. In some accents, that reads as an extra emphasis, and so it’s worth learning how to make linking /r/ if it is unfamiliar to you.

Things get confusing around medial /r/, or /r/ that happens in the middle of a word. If the medial /r/ is between two vowels and initiates the second syllable, then it is a consonant /r/, e.g. “arrest, Toronto, ”—the consonant /r/ initiates the second syllable. There may also be a vowel /r/ on the end of the first syllable, but it is optional—depending on what kind of accent you’re speaking, rhotic or non-rhotic. If the medial /r/ is followed by a consonant, and it doesn’t initiate the second syllable (i.e. it isn’t between two vowels), it is a vowel /r/ only, e.g. “herding, farmer, sharpen”. If it is in the middle of a single syllable word and is followed by another consonant, the /r/ is also a vowel /r/, e.g. “bark, word, term, lurk”.

So far, we have only met Consonant /r/. Vowel /r/, as a concept, should get clearer when we explore the seven R-coloured vowels, [ɚ, ɝ, ɪɚ, ɛɚ, ʊɚ, ɔɚ, ɑɚ] as heard in the words “Bernice, burr, beer, bear, boor, boar, bar.”

Practice material for [ɹ] and /r/:

Audio Quiz 2

Audio Quiz 3

Unfamiliar Consonant Nonsense Exercise 2

[ ʃ, ʒ, θ, ð, ŋ, ʍ, ɫ, tʃ, dʒ, ɹ ]

The following nonsense words all use the vowels heard at the end of “ski” [i]or “Zulu” [u]Speak them out loud, and see if you can get your reading up to “normal” speed!

You can listen to these words here:

First, try speaking after the recording, so it models the syllables for you, then, try saying the words before you hear it on the recording, and it will “correct” you.

| 1. ʃiʃ | 7. ðiɫ | 13. tʃitʃ | |||

| 2. ʍuɫ | 8. ʒuʒ | 14. ɹiʃ | |||

| 3. ɹuŋ | 9. tʃuð | 15. ʃuŋ | |||

| 4. θiθ | 10. dʒudʒ | 16. ʒið | |||

| 5. ʒidʒ | 11. ʍiθ | 17. ðuð | |||

| 6. θutʃ | 12. dʒuʒ | 18. dʒiŋ |

Unfamiliar Consonant Nonsense Exercise 3

The following nonsense words mix the symbols above with the symbols whose shapes are more familiar, [p, b, t, d, k, ɡ, s, z, f, v, m, n, l, w, h].

N.B. These syllables were made randomly, so occasionally the syllables are words, rather than nonsense ones.

These words can be heard here:

Try to say the words first, and then have the audio file give you the pronunciation.

| 1 | ɹuʃ | θuk | diʃ | vidʒ | butʃ | ziθ | biʃ |

| 2 | buð | við | ɹup | witʃ | biŋ | ʒum | ʍut |

| 3 | ðid | tuʒ | dið | vitʃ | budʒ | zuð | bidʒ |

| 4 | hiθ | miʃ | hitʃ | pidʒ | fuŋ | niŋ | lidʒ |

| 5 | dʒuk | tʃud | ditʃ | θuf | didʒ | ʒip | diŋ |

| 6 | fiŋ | tiθ | duð | tʃib | ðin | wið | ðiz |

| 7 | viθ | pitʃ | vuʃ | buʒ | ziʒ | siʃ | wuŋ |

| 8 | fuθ | siθ | fið | tið | dudʒ | tidʒ | dʒuf |

| 9 | ɡidʒ | puθ | fuð | ʃuv | duŋ | ʃuɡ | ɡuʃ |

| 10 | ɡitʃ | pið | fuʒ | suð | fidʒ | puŋ | hiʒ |

| 11 | ɡiʒ | muʃ | ɡiθ | ʃid | fitʃ | pudʒ | huθ |

Unfamiliar Consonant Nonsense Exercise 4

Similar to the words above, listen to the audio file listed below and write out the ipa symbols for the syllables you hear. Each number is followed by 7 nonsense syllables. This is a very long exercise: do part of it now, and return to it later for review purposes.

The audio can be heard here:

ADD ACTIVITY HERE

Fish-Hook: [ɾ]

This can be heard here:

| Symbol | Spelled | As in… | Name | Notes | |||

| [ɾ] | “t/d” | “better” | Fish-hook | This symbol evolved from the lowercase R symbol because it is used for medial R in some forms of heightened British speech, as in “very”. | |||

| The Sound & the Action: The tapped /r/ is similar to a trill, except that it is only a single stroke of the tongue off the articulator it strikes—in this case, the alveolar ridge. In North America, the sound represented by Fish-hook is used for the sound that is spelled “t” in many words in an intervocalic position—between two vowels—and in an unstressed syllable (e.g. this wouldn’t happen on “attire,” where the /t/ is stressed, but it would on “attic”, where it’s unstressed). Though this is often transcribed inaccurately as a voiced alveolar stop plosive [d], the sound is actually a tap of the alveolar ridge. It also can happen between two words, with the [ɾ] linking them, as in “it is,” [ɪɾ ɪz]. In a heightened non-rhotic accent, it might also be used as a Linking /r/, as in “there are,” [ðɛɾ ͜ ɑ].

It is argued that the Voiced Alveolar Tap is also used for /d/ between two vowels, so that words like latter and ladder sound the same to those who have this kind of /t/ in their speech. Phrases like “Lordy, lordy, look who’s forty!” are great examples of how this works—note that the <r> in this example, lordy, is a vowel /r/ that is part of the previous syllable, and so the tap is coming between two vowel sounds, not after a consonant /r/. In many accents of English, the tapped /r/, [ɾ] is used for consonant /r/ generally, as in read, rid, raid, red, rod. Initial tapped /r/ often sounds like it has a very, very short vowel before the tap. Frequently [ɾ] is used for the /r/ in consonant clusters, [tɾ– , dɾ– , kɾ– , ɡɾ– , pɾ– , bɾ– , fɾ– , θɾ– , stɾ– , spɾ– , skɾ– , ʃɾ-], as in try, dry, cry, grime, pry, bride, fry, thrice, stripe, spry, scribe, shriek. |

|||||||

| Linguistic Term: Voiced Alveolar Tap. | |||||||

| Spellings | sitting, waiting, writer, beauty, get off | ||||||

Drag and Drop: Practice Material for [ɾ] vs [t]

J or Yod: [j]

This can be heard here:

| Symbol | Spelled | As in… | Name | Notes | |||

| [j] | “y” | “yellow” | J [dʒeɪ] or yod [jɒd] | This symbol isn’t new, but the sound it represents doesn’t often make sense at first for most English speakers. If you think of this symbol as it is used in the Norwegian loan-word fjord, or how it’s used in Scandinavian languages, you’ll catch on very quickly—I always think of ABBA singer Björn Ulvaeus, and Icelandic singer Björk. | |||

| The Sound & the Action: This sound is termed a semi-vowel because it is essentially the vowel [i]“ee” pushed to the extreme, up toward the hard palate. | |||||||

| Linguistic Term: Voiced Palatal Approximant, often known as “Yod”. | |||||||

| Spellings | onion, Europe, monseigneur, hallelujah, brilliant, unite, yard, beyond | ||||||

ADD YOD ACTIVITY HERE

The Glottal Stop: [ʔ]

This can be heard here:

| Symbol | Spelled | As in… | Name | Notes | |||

| [ʔ] | The Glottal Stop | This symbol is a question mark (?) without the dot. | |||||

| The Sound & the Action: The Glottal Stop [ʔ] is made with a closure in the glottis, which is the space between the vocal folds in the larynx. Like other voiceless stop plosives, air pressure builds up behind the closed folds and then bursts forth into a voiced, or voiceless sound. For example, the negative, nasalized interjection meaning no—”UH-uh” [ˈʔʌ̃ ʔʌ̃] (note the nasal diacritic mark above the [ʌ] vowel) or, said with the mouth closed, “Mm-mm” [ˈʔm ʔm]; the positive interjection which means yes—”uh-HUH” [ʔʌˈhʌ̃], or, with the mouth closed, “mm-HM” [ʔm ˈhm]. But you could also use in it a whispered, voiceless utterance of “UH-oh” [ˈʔʌ ʔoʊ̯]. (Unless you’re Scooby-Doo, in which case, those glottals are replaced with [ɹ]—[ˈɹʌ ɹoʊ̯].

Perhaps most famously it is used in the working-class London accent (aka Cockney) in place of the medial, unstressed /t/, as in better [ˈbɛʔə]; it cannot be used in place of a medial, stressed /t/, as in protect [pɹəˈtɛkt]. In most North American speech, the glottal stop is used in at least three ways. First, it is used to initiate or emphasize words that begin with a vowel, e.g. Eric Armstrong [ˈʔɛɚɹɪk ˈʔɑɚmstɹɒŋ]. (Note that you don’t have to use glottals before vowels, but many of us do!) Secondly, it is used by many speakers to replace [t]’s before [n], where bitten becomes either [ˈbɪʔ͜tn̩]—note that the /t/ has ɡlottal reinforcement before the syllabic /n/—or as [ˈbɪʔɪn], with a short vowel between the ɡlottal stop and the /n/. Similarly, words like Hinton either become [ˈhɪnʔn̩], aɡain with a syllabic /n/, or, with a nasalized initial vowel, [ˈhɪ̃ʔɪn], where the ɡlottal is followed by a vowel before the final /n/). Finally, the glottal stop is frequently used to reinforce an unreleased final stop, which is co-articulated with the glottal, at the end of an utterance. For example, stop [stɒʔp], stab [stæʔb], bat [bæʔt], bad [bæʔd], back [bæʔk], bag [bæʔɡ]. |

|||||||

| Linguistic Term: Voiceless Glottal Stop | |||||||

| Spellings | Note there is no common way of spelling a glottal stop, though sometimes people use an apostrophe to indicate it as in water “wa ‘er”. | ||||||

Drag and Drop: Practice Material for [ʔ], [t], [ɾ], and [h]

Review Session 3

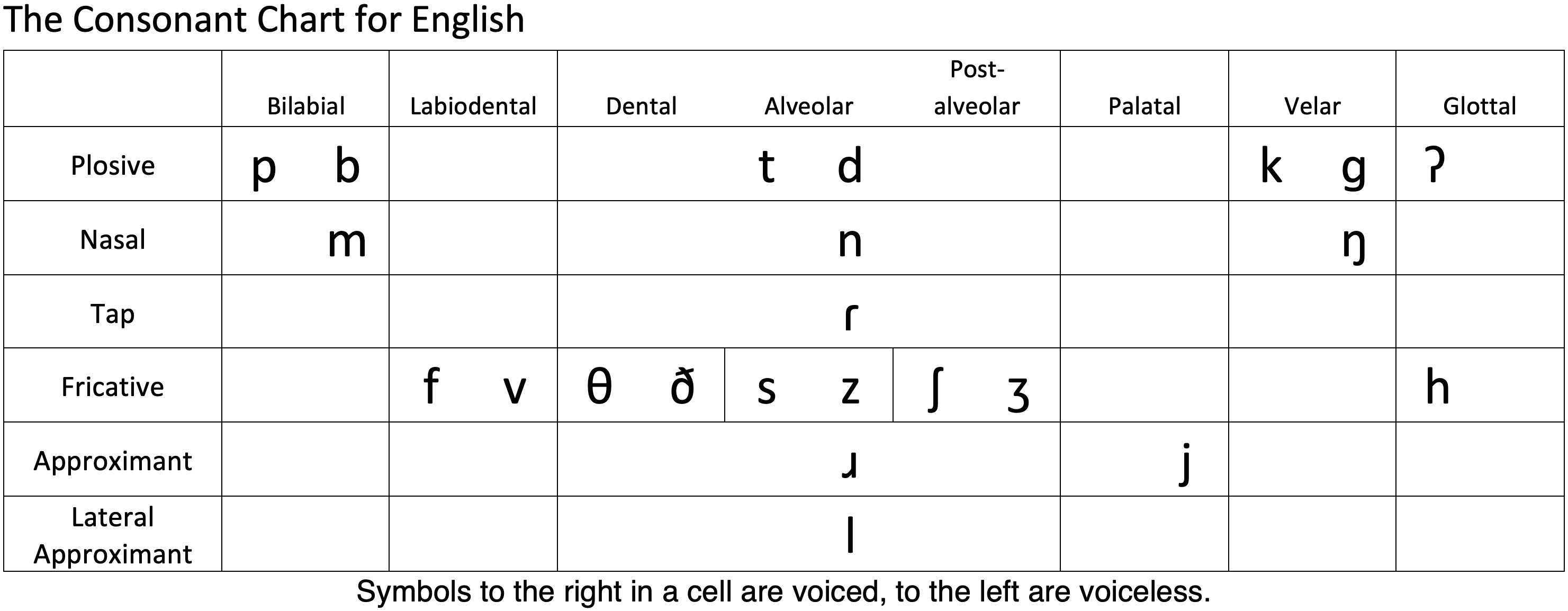

The Consonant Chart for English Drag-and-Drop-the-Symbols

- MRI 2. Janet Beck. Voiceless postalveolar fricative. Seeing Speech. Glasgow: University of Glasgow, 2018. Web. 21 August 2024. https://seeingspeech.ac.uk/ipa-charts/?chart=1&datatype=4&speaker=1#location=643 ↵

- MRI 2. Janet Beck. Voiced postalveolar fricative. Seeing Speech. Glasgow: University of Glasgow, 2018. Web. 21 August 2024. https://seeingspeech.ac.uk/ipa-charts/?chart=1&datatype=4&speaker=1#location=658 ↵

- MRI 2. Janet Beck. Voiceless dental fricative. Seeing Speech. Glasgow: University of Glasgow, 2018. Web. 21 August 2024. https://seeingspeech.ac.uk/ipa-charts/?chart=1&datatype=4&speaker=1#location=952 ↵

- MRI 2. Janet Beck. Voiced dental fricative. Seeing Speech. Glasgow: University of Glasgow, 2018. Web. 21 August 2024. https://seeingspeech.ac.uk/ipa-charts/?chart=1&datatype=4&speaker=1#location=240 ↵

- MRI 2. Janet Beck. Voiced velar nasal. Seeing Speech. Glasgow: University of Glasgow, 2018. Web. 21 August 2024. https://seeingspeech.ac.uk/ipa-charts/?chart=1&datatype=4&speaker=1#location=331 ↵

- MRI 2. Janet Beck. Voiceless labial-velar fricative. Seeing Speech. Glasgow: University of Glasgow, 2018. Web. 21 August 2024. https://seeingspeech.ac.uk/ipa-charts/?chart=3&datatype=4&speaker=1#location=653 ↵

- MRI 2. Janet Beck. Voiced alveolar approximant. Seeing Speech. Glasgow: University of Glasgow, 2018. Web. 21 August 2024. https://seeingspeech.ac.uk/ipa-charts/?chart=1&datatype=4&speaker=1#location=633 ↵

- MRI 2. Janet Beck. Voiced alveolar tap. Seeing Speech. Glasgow: University of Glasgow, 2018. Web. 21 August 2024. https://seeingspeech.ac.uk/ipa-charts/?chart=1&datatype=4&speaker=1#location=638 ↵

- MRI 2. Janet Beck. Voiced palatal approximant. Seeing Speech. Glasgow: University of Glasgow, 2018. Web. 21 August 2024. https://seeingspeech.ac.uk/ipa-charts/?chart=1&datatype=4&speaker=1#location=106 ↵

- MRI 2. Janet Beck. Voiceless glottal plosive. Seeing Speech. Glasgow: University of Glasgow, 2018. Web. 21 August 2024. https://seeingspeech.ac.uk/ipa-charts/?chart=1&datatype=4&speaker=1#location=660 ↵